Saul Bellow once said that he could make his enemies very unhappy simply by describing them. Quite a boast; and yet, who among us would have been eager to find himself on the receiving end of a Bellow character sketch? The author of Herzog was probably not the first great comic novelist to have recognized the damage that can be inflicted simply by writing down what people are like. When we read Jane Austen or Charles Dickens or Evelyn Waugh or Kingsley Amis, it can seem as though human beings are so foolish, so self-absorbed, so willfully blind and interminably verbose that the novelist need only record what they say and do in order to furnish a whole book’s worth of exuberantly loathsome gargoyles.

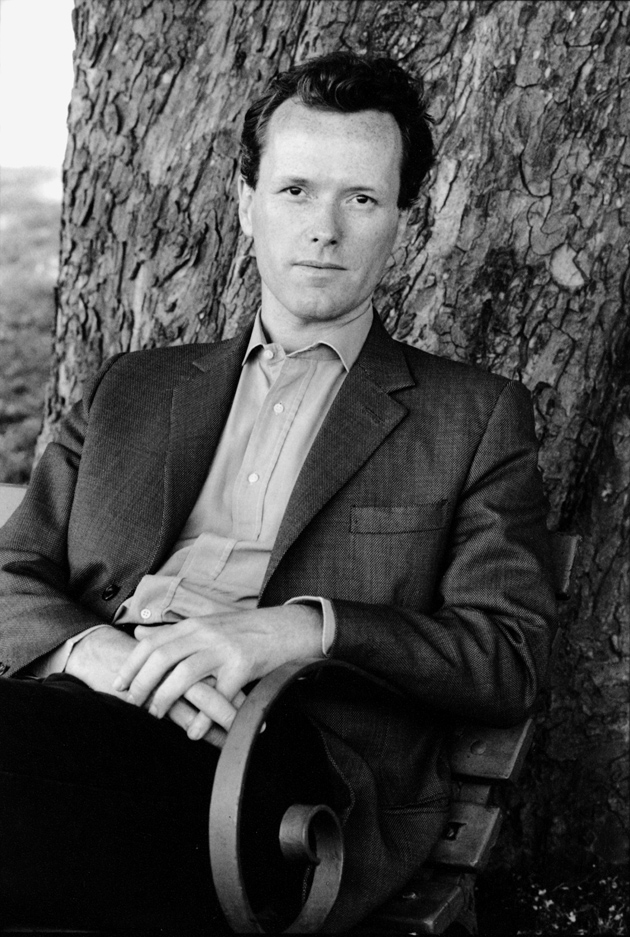

The English novelist Edward St. Aubyn, one of the great comic writers of our time, must have some very unhappy enemies indeed. His sprightly, caustic, and harrowing novel sequence about the blue-blooded Melrose family—a family that, “although it had done nothing since, had seen the Norman invasion from the winning side”—is stuffed with vile and vivid high-born personages, most of whom, St. Aubyn has let it be known, are “uninvented.” One of the incidental pleasures his work affords is that of imagining these real-life prigs and snobs and bores opening one of his novels to find themselves mercilessly embalmed on the page. Thus we have Emily Price, who “as a guest…had three main drawbacks: she was incapable of saying please, incapable of saying thank you, and incapable of saying sorry, all the while creating a surge in the demand for these expressions.” Elsewhere we encounter a shameless, fawning social climber whose

grinning mouth was at once crude and cruel. When he tried to smile, his purplish lips could only curl and twist like a rotting leaf thrown onto a fire. Obsequious and giggly with older and more powerful people, he turned savage at the smell of weakness, and would attack only easy prey…. Like many flatterers, he was not aware that he irritated the people he flattered. When he had met the Wooden Duke he had poured himself out in a rich gurgling rush of compliments, like an overturned bottle of syrup.

In Some Hope (1998), the third Melrose novel, there is a cameo featuring none other than Princess Margaret, the Queen’s late sister, and St. Aubyn clearly has great fun trampling the carefully tended flower bed of her royal pomp and self-conceit. At one moment, during a glitzy dinner party at an old country house, Monsieur d’Alantour, the former French ambassador, accidentally flicks “glistening brown globules” of gravy “over the front of the Princess’s blue tulle dress.” Any hope that she might see the funny side of this mishap is soon laid to rest:

The Princess compressed her lips and turned down the corners of her mouth, but said nothing. Putting down the cigarette holder into which she had been screwing a cigarette, she pinched her napkin between her fingers and handed it over to Monsieur d’Alantour.

“Wipe!” she said with terrifying simplicity.

We often hear that fictional characters, to be memorable, must surprise us; but it is equally important that they be predictable, that they be seen to live up to the expectations of those in their fictional world. This is something St. Aubyn understands perfectly. From the moment they open their mouths, we grasp that his moneyed narcissists are the kind of people who like nothing more than to hear themselves speak; who have polished their plush phrases at home before coming out to try them in society; who feel that their own existence is far more real, and far more distinguished, than that of anyone else. In other words, we grasp that his characters are always like this, and that they probably couldn’t behave otherwise, even if they wanted to. Brushing aside the suggestion that people often undergo profound personal transformations during the course of their lives, one of St. Aubyn’s most incorrigible characters defiantly proclaims: “Ever since I was a little boy, I’ve been in the high summer of being me, and I intend to go on chasing butterflies through the tall grass until the abrupt and painless end.”

Of course, a fictional universe swarming with such beasts of unreflective self-assurance would be uninhabitable without the presence of at least one more or less sane, clear-sighted character. (Try imagining Pride and Prejudice without Lizzie Bennett.) In St. Aubyn’s work this role falls to Patrick Melrose, from whom a new edition of the Melrose novels takes its name. Although he is the child of extraordinary wealth and privilege—he comes from a world of people who are “rich as God”—Patrick is an altogether less complacent, more self-divided figure than St. Aubyn’s other characters.

Advertisement

We first meet him in Never Mind (1992), a brisk, horrifying novel that takes place during a single summer day in balmy, pine-scented Provence, where Patrick is on holiday with his parents. He is five years old, intelligent, imaginative, and—like Henry James’s Maisie—painfully at the mercy of the vicious adult world that surrounds him. His parents’ marriage is a travesty. During a dinner party, his beleaguered, alcoholic mother, Eleanor, excuses herself to go check on Patrick, but her husband, David, a charismatic sadist who believes that “what redeemed life from complete horror was the almost unlimited number of things to be nasty about,” cannot let the moment pass without humiliating her in front of their guests:

“Not leaving us I hope, darling,” said David.

“I have to…I’ll be back in a moment,” Eleanor mumbled.

“I didn’t quite catch that: you have to be back in a moment?”

“There’s something I have to do.”

“Well, hurry, hurry, hurry,” said David gallantly, “we’ll be lost without your conversation.”

Without Patrick, the book would still be a scabrous social satire on a world where “people spend the evening dining with people they’ve spent the day insulting”; but it is his innocent and defenseless presence (“Everybody used his name but they did not know who he was,” he heartbreakingly reflects at one point) that throws into relief the moral rot of some of the other characters and elevates Never Mind to the level of tragedy.

In the book’s most shocking scene, Patrick is raped by his father. The incident is described, from Patrick’s perspective, with a cold-eyed meticulousness (“He could hear his father wheezing, and the bedhead bumping against the wall”) that makes the child’s abjection all the more unbearable. By the end of the book, we realize we have witnessed a day from which, though he has survived, Patrick will never fully recover. “One day,” he thinks, as he lies sleepless and unconsoled in bed, “he would play football with the heads of his enemies.”

Bad News (1994), the next book in the series, takes place some twenty years later. Patrick is by now an accomplished heroin addict (“he always wanted smack, like wanting to get out of a wheelchair when the room was on fire”) whose yearning for drugs is matched only by his yearning for suicide. He is visiting Manhattan, where his father has died unexpectedly, thereby cheating Patrick of “the chance to transform his ancient terror and his unwilling admiration into contemptuous pity for the boring and toothless old man he had become.” Thus thwarted, Patrick has himself become an angry and far from toothless young man, whose hectic and compulsive inner life (“How could he think his way out of the problem when the problem was the way he thought”) all but prevents him from recognizing the existence of other people. When he is asked how his girlfriend, Debbie, is getting on, he almost falls to pieces:

The question filled Patrick with the horror which assailed him when he was asked to consider another person’s feelings. How was Debbie? How the fuck should he know? It was hard enough to rescue himself from the avalanche of his own feelings, without allowing the gloomy St Bernard of his attention to wander into other fields.

That cheeky extended metaphor, which in another writer might have seemed ostentatious, here feels entirely appropriate, capturing as it does the glazed detachment with which Patrick regards his own difficulties. However gruesome the subject—and it usually is gruesome—St. Aubyn’s prose always moves with a light touch. It is this that saves (and more than saves) the Melrose books from the dangers of melodramatic excess and maudlin self-pity.

Unlike the hero of many a multigenerational novel cycle before him, Patrick does not end up becoming a novelist: he becomes a barrister. Nevertheless, in Some Hope and Mother’s Milk (2006), which chart, respectively, Patrick’s efforts to stay clean of drugs in his early thirties and, ten years later, to raise a family, he does begin to acquire a kind of writerly detachment, the capacity to see other people—and in particular his mother and father—as other people, with complex and autonomous inner lives.

This, to be sure, does not mean he comes to hate his parents any less. Eleanor, who in Never Mind seemed to suffer from her husband’s cruelty almost as much as Patrick, is revealed to be a rather unpleasant figure in her own right. In Mother’s Milk, motivated by a delusive grandiosity, she disinherits Patrick and bequeaths the family’s house in southern France to a group of New Age hucksters, who set about turning it into a Transpersonal Foundation. Later on, ravaged by a series of strokes, Eleanor asks Patrick to have her euthanized, and while it seems possible that her “demands for help were not an offer to clear herself out of the way, but the only way she had left to keep herself at the centre of her family’s attention,” he takes a deep breath and makes the necessary arrangements. Among these arrangements is a letter of consent, in which Patrick movingly ventriloquizes his mother’s suffering:

Advertisement

I have had several strokes over the last few years, each one leaving me more shattered than the last. I can hardly move and I can hardly speak. I am bedridden and incontinent. I feel uninterrupted anguish and terror and frustration at my own immobility and uselessness. There is no prospect of improvement, only of drifting into dementia, the thing I dread most. I can already feel my faculties betraying me. I do not look on death with fear but with longing. There is no other liberation from the daily torture of my existence. Please help me if you can.

One thing that makes the Melrose novels such shrewd studies of social life is the way in which they always keep an eye firmly fixed on those horrific realities—aging, isolation, death—that social life exists to conceal and distract us from. At the last minute, perhaps not surprisingly, Eleanor changes her mind and asks that Patrick “do nothing.” He isn’t going to get rid of her that easily.

Between the end of Mother’s Milk and the start of At Last, the latest and apparently final Melrose novel, Eleanor has died. “The dead are dead,” says the booming, compulsively aphoristic David Melrose, in Never Mind, “and the truth is that one forgets about people when they stop coming to dinner. There are exceptions, of course—namely, the people one forgets during dinner.” At Last, which takes place in London on the day of Eleanor’s funeral, suggests that the dead might be rather more tenacious than that.

The new novel is all about the sway held by the dead over the living, and while its title registers, among other things, Patrick’s sense of relief at his hard-won orphanhood (“I think my mother’s death is the best thing to happen to me since…well, since my father’s death”), the book makes it clear that he is far from done with his mother, and that she is far from done with him. As one elderly character reflects as she contemplates a detested father-in-law: “He had died almost forty years ago, but she wanted to kill him every day.”

As you would expect, St. Aubyn, like Evelyn Waugh in The Loved One, has some fun with the pieties of the funeral business. On a wall at the funeral parlor where he has come to visit his mother’s corpse on the evening before the funeral, Patrick notices “a framed photograph of a woman kneeling by a black box from which a dove was only too pleased to be set free.” The next day, before the service begins, we are treated to the following curt interaction:

“We can start whenever you’re ready, sir,” said the usher, somehow hinting at the queue of corpses that would pile up unless the ceremony got going right away.

Patrick scanned the room. There were a few dozen people sitting in the pews facing Eleanor’s coffin.

“Fine,” he said, “let’s begin in ten minutes.”

“Ten minutes?” said the usher, like a young child who has been told he can do something really exciting when he’s twenty-one.

The service itself is a horror show of inspirational readings and saccharine tributes, the most wildly off-the-mark of which comes from one of Eleanor’s New Age comrades, Annette, who praises the way in which she “never lost a connection to the child-like quality that made her believe so passionately that justice could be achieved.”

Patrick, of course, knows otherwise. As the eulogists one by one set forth their air-brushed image of his mother, he, along with his compassionate ex-wife, Mary, reflect on what Eleanor was really like. Mary is unable to forgive Eleanor for failing to protect Patrick against his father when he was a child:

Once his depravity was on full display, how could Eleanor escape the charge of colluding with a sadist and a paedophile? She had invited children from other families to spend their holidays in the South of France and, like Patrick, they had been raped and inducted into an underworld of shame and secrecy, backed by convincing threats of punishment and death.

Patrick himself, although he is now able “to imagine how terrified Eleanor must have been…to have abandoned her desire to love him…and be compelled to pass on so much fear and panic instead,” is nevertheless forced to acknowledge “the deeper truth that he had been a toy in the sadomasochistic relationship between his parents.” He sees a desire to avoid confronting her guilt at all costs as the motive behind her embrace, first, of charitable work, and then of New Age quackery:

When Patrick’s childhood had ended and the inarticulate echoes of her own childhood faded, Eleanor stopped supporting children’s charities, and embarked on the second adolescence of her New Age quest. She showed the same genius for generalization that had characterized her rescue of children, except that her identity crisis was not merely global, but interplanetary and cosmic as well, without sinking one millimeter into the resistant bedrock of self-knowledge. No stranger to “the energy of the universe,” she remained a stranger to herself.

This is acute and comprehensively damning, but it can also feel as though Eleanor’s character is being statically insisted upon rather than dynamically evoked. After a while—there are pages and pages of such meditative character analysis—we long to see Eleanor’s blindness and neurosis in action, rather than simply in paraphrase. For those who have read the previous four Melrose novels this may seem like less of a problem, but it does sometimes make At Last feel more like a postscript than an autonomous work in its own right.

Still, unlike those of David and Eleanor Melrose, the sins of At Last are venial. Readers will be quick to forgive a writer who has one of his characters think, as he is being carried off by paramedics after a stroke, “He must tell them he was not an organ donor.” It is in a different and more tender register, however, that the book unexpectedly draws to a close. “An only life can take so long to climb/Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never,” says Philip Larkin. For much of the Melrose novels it had seemed that this would serve rather well as Patrick’s epitaph. Against all the odds, though, he has come through. Orphaned, divorced, separated from his children, and still bearing the scars of his own childhood trauma, Patrick has nevertheless managed to climb clear of his wrong beginnings and arrive at an illusionless, fortifying sanity.

At the end of the book, having run the gauntlet of awkward and painful social interplay at his mother’s funeral, Patrick finally makes it home to his flat—“in order to be unconsoled,” as he bluntly thinks to himself. The solitude scares him at first: without the distraction of other people, he worries he will be overwhelmed by despair, confusion, and dread. Something else happens instead, and the surprise, for once, is a pleasant one:

Perhaps whatever he thought he couldn’t stand was made up partly or entirely of the thought that he couldn’t stand it. He didn’t really know, but he had to find out, and so he opened himself up to the feeling of utter helplessness and incoherence that he supposed he had spent his life trying to avoid, and waited for it to dismember him. What happened was not what he had expected. Instead of feeling the helplessness, he felt the helplessness and compassion for the helplessness at the same time. One followed the other swiftly, just as a hand reaches out instinctively to rub a hit shin, or relieve an aching shoulder.

This Issue

April 5, 2012

They’re the Top

We’re So Exceptional

Who Is Peter Pan?