There is a heightened sense of freedom and experimentation, touched with a gentle, deadpan humor, pervading the work of the American painter Forrest Bess (1911–1977). Looking at his unusually small pictures, which are like so many short, enigmatic tales—they were made from roughly the middle 1940s to the early 1970s—we have no idea, from work to work, what will come next. To a degree that sets him apart from many artists, Bess, who is the subject of a recent good-sized show at Christie’s and a small exhibition that is part of the Whitney Biennial, rarely repeated a motif. And in pictures that blur distinctions between abstraction and representation, we encounter diminutive worlds that, while they can make us think of shapes and forms associated with modern artists such as Arp, Malevich, Picabia, and Brancusi, are at the same time a little like whimsical, nonsensical illustrations, or diagrams, that one might see in books for young children.

All this is surprising because Bess, who has long had an underground reputation in the art world, is a figure one would associate less with freedom or humor than with something driven or portentous. A contemporary of the Abstract Expressionists and an artist who showed in New York in the 1950s and 1960s, Bess was a kind of classic loner. He worked with canvas sizes that were in those years unfashionably unheroic. He was based in Texas, where he supported himself as a commercial fisherman in the Gulf of Mexico, and, setting him even further apart, his pictures, he made clear, came to him in visions. They were about psychosexual forces and theories Bess had about freeing himself of his anxieties—even attaining immortality. He believed it could happen through his becoming a hermaphrodite. It was a theory he was willing to test out on himself, and when he was nearly fifty he performed what he thought was the requisite surgery on his own body.

In the years since his death, Bess has been admired in part for his very independence. He was given a retrospective by the Whitney in 1981, and in 1984 his work was seen in a traveling show with that of two other uncategorizable painters of his time: Alfred Jensen, whose quilt-like pictures are based on abstruse number charts and color theories, and Myron Stout, a fellow Texan who also used small canvas sizes and in whose stark black-and-white pictures different abstract shapes—and parts of the body—take on an emblematic intensity. Decades after that show, Jensen, Stout, and Bess are still looked to as models, especially by young painters, I think, for going your own way.

Bess’s legacy, though, has become increasingly impalpable. Although there are works by him in the collections of the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art, they are pictures that are on view only occasionally. It is safe to say that his art is hardly ever visible in any of our major museums, and no book reproducing the scope of his work is currently available. No gallery has exhibited his pictures in decades, and his last significant show in New York was in 1988. For some people his name may have more to do with disquieting aspects of his personal life than with his art.

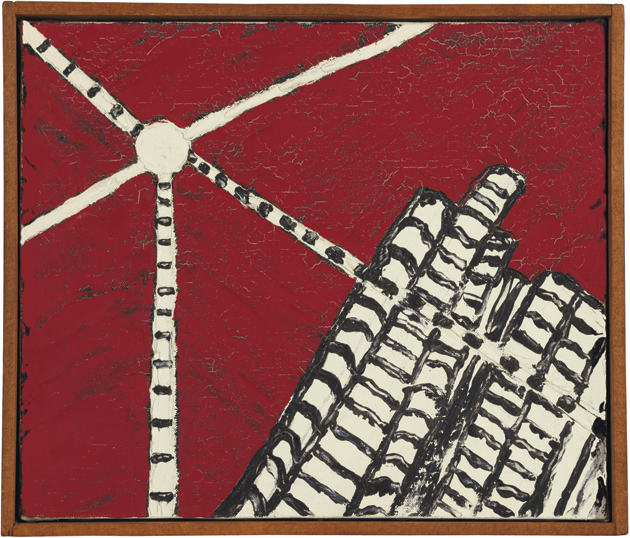

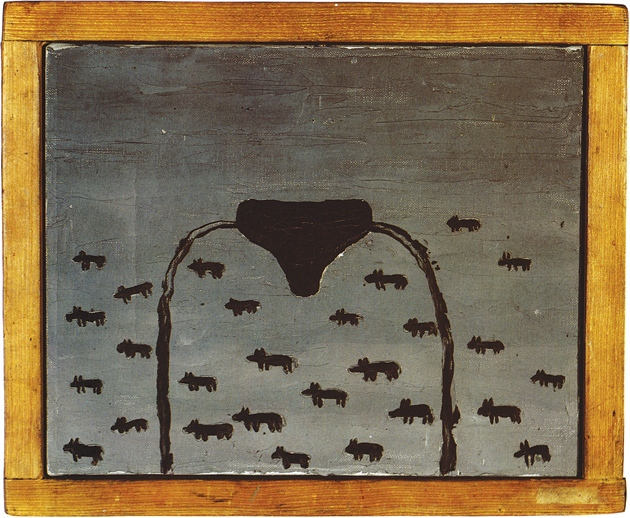

The two exhibitions this spring are thus very welcome events, though not all the works on view represent Bess at his finest.* If the artist who emerges is not a grand or imposing figure, his pictures by and large remain able to keep us guessing in fresh and pleasurable ways. They have something of the loose, informal nature of cartoon animation, but without the coy winks to the audience that animation can have. A punchy and compactly dramatic untitled picture from 1960, at Christie’s, for example, shows a radio tower–like structure that appears to send bolts of power (see illustration). One bolt hits another structure, which seems to pull back in response. The 1946–1947 Untitled (The Void I), which was also at Christie’s, is like a close-up of an hourglass, with a collection of doodle shapes making its way from the top of the glass to the bottom. In the endearing Untitled (No. 31), from 1951, which is at the Whitney, a herd of some sort of animal, drawn with a stick-figure speed and simplicity, moves along under an overhead sign that resembles a bicycle seat.

What turns out to give Bess’s art its particular strength, though, is less its variety or its fable-like character than the distinctive physical presence of his pictures. As objects, they embody in surprising ways feelings of forcefulness and temerity and, on the other hand, vulnerability and modesty. Because his pictures are generally so small—many are a foot or less on a side—Bess gave them somewhat chunky wood strip frames. He clearly nailed them together himself. Often a weathered, brown-red color, they invariably enrich the textures and colors of paintings that, made by an artist who rarely mixed his colors and seemed not to care whether his painted surfaces were slab thick or so thin the canvas shows through, generally can stand some textured note.

Advertisement

When Bess’s works are reproduced, they are sometimes seen in their frames, and this is appropriate because the thickish, occasionally ill-fitting strips are almost as much a part of the very image of a Forrest Bess as the containing wood box is for a work by Joseph Cornell (who was a contemporary of his). Bess’s frames can make it seem as if, looking at his paintings, we face miniature stage sets. This feeling is corroborated by Bess’s brushwork, which, loose and rarely labored, is rather like that of many stage backdrops. But the frames ultimately make a kind of two-sided psychological point. For paintings that come primarily in baby sizes, the heavyish wood strips seem to add a needed degree of assertiveness and protection. But they also impart an emotional warmth to works that, on their own, and in their unembellished and nonchalant way, can be surprisingly aggressive.

As it happens, Bess’s life story centers on an overwhelmingly felt sense of two-sidedness. And if his pictures, encountered without a viewer’s knowing anything about the person who made them, suggest an artist who moved from image to image with a degree of lawlessness, or at least an insouciance, Bess’s biography suggests a man who was as hounded by his theories as he was liberated by them.

Born in Bay City, Texas, he studied architecture at Texas A&M and the University of Texas, and he went on to spend time in Mexico, paint, and serve in the Army Corps of Engineers during World War II. But he experienced a vision at age four, and by his middle thirties, now out of uniform, he was experiencing them regularly. He was also making full-fledged Forrest Bess paintings from those visions. It was at this time that he set himself up, near where he was born, as a bait fisherman, working entirely from his own boat and living by himself, in a dwelling he built from found materials, on a strip of land that could be reached only by boat.

A voracious consumer of books on religion, mythology, physiology, mysticism, philosophy, alchemy, and the psychology of sex, he seems already from these postwar years to have been on his mission to attain a union of both sexes in himself. It was a mission, it has been noted in the commentary on him, that perhaps sprang up as a way of handling a discomfort with homosexual inclinations. A gregarious man—and, certainly in his earlier years, a lanky, handsome guy with a pipe invariably in his hand or mouth—he was happy to expound on his notions to anyone. Over the decades, he wrote some two thousand letters, many to sex researchers. He corresponded with Jung, told President Eisenhower about his ideas in a letter, and was in touch with the Columbia art historian Meyer Schapiro about his sexual goals, his visions, and his painting from this time in the late 1940s until a few years before his death.

By 1960, he was ready to see his theory through. Getting quite plastered, as he told Schapiro, he performed his own surgery on his genitals, opening a hole in his scrotum that presumably would allow him to be impregnated and give him his status as a hermaphrodite. However this (and a subsequent) operation altered his body or his thinking, his life was turned upside down the following year when Hurricane Carla devastated the Gulf coast. It destroyed his house and nearly everything he owned. He was able to save some of his paintings, and he moved to his mother’s place in Bay City. He continued to paint, and he toyed with making movies and sculpture. But the fifteen or so years that remained of his life were marked by heavy drinking and eventually periods of delusion. When he died in a state hospital, of cancer and other complications, his condition was listed as paranoid schizophrenic.

Bess’s life story is so excruciatingly vivid and disturbing that it can at first cast a spell over his pictures. Specific and concrete about many things, he drew out a legend of the symbols he was using in his art, and this table is included in the Christie’s catalog. A different version is even more prominently on view on a wall plaque at the Whitney. The charts show how different shapes in his pictures might mean, to use Bess’s words, “to cut shallow,” or “hole gets bigger,” or “hermaphrodite.” Some shapes are more metaphoric in tone, representing impulses or thoughts such as “to contain” and “to go north,” while others signify “life (dilated urethra)” and “death (undilated urethra).”

Advertisement

The Whitney show, which has been organized by the artist Robert Gober and given the title “The Man That Got Away,” pushes quite far in making us aware of Bess’s obsession. In a forthright statement placed on a gallery wall, Gober points out that Bess “longed” to have his paintings and documents concerning his larger quest exhibited together. In an effort to honor the artist’s attentions, letters about what he saw as his mission and photographs he managed to take of his operation are therefore on display, padded with more strictly biographical materials. The result for many viewers will be that Bess and his art together form a freakish curiosity, or that, whatever qualities one ascribes to his work, he was a kind of “outsider” artist, a figure who was not altogether conscious of how he operated.

A case could be made that this was so—that, essentially copying out his paintings from images already in his head (as he described his process), and often noting that he himself was at a loss to explain his visions, he worked in the somewhat automatic way of a number of artists who made their artworks while living in institutions. The late Czech photographer Miroslav Tichý, who was not institutionalized but sometimes is thought of as an outsider artist (because of his highly eccentric manner of living and working), shot his pictures with an automatic, even “unthinking,” speed. Yet in some sense Bess was the polar opposite of such creators. He didn’t paint in a seemingly rote way, revisiting the same terrain again and again. He made one brand-new start after another.

Maybe more importantly, there is hardly a clear correlation between Bess’s symbols and our experience of his paintings. In an untitled 1957 picture in the Whitney, for instance, two white rectangles in a pitch-black space appear before us like windows in the night (see illustration). From the edge of the picture an amorphous, red, pawlike shape seems to reach toward one of the “windows,” as if to say, “You come with me.” Based on his chart of symbols, the image probably has something to do with the themes of “stretching” and “containing” that the artist obsessed about. The picture, though, surely has a life that is independent of the concepts it is built on. It comes across as an original blend of the geometric, the expressionistic, the austere, and the silly.

Yet Gober is right in not wanting us to ignore the painter’s personal quest. To leave out Bess’s aspirations is to be stuck with a collection of random images. And when Bess’s pictures are presented as so many camouflaged views, acts, and moments in a sexualized world, he becomes to his advantage more connected with other American painters and sculptors of his generation. Joseph Cornell, Louise Bourgeois, and Myron Stout, for instance, come to mind as artists who also handled in masked or indirect ways subjects such as romance and infatuation, one’s sexual identity, and the carnal force of abstract shapes. That Bess went literally into his own sexualized world is undeniably fascinating. That he came out of his trip with so many beckoningly strange and sweet-tempered views of it is, however, the real mystery.

-

*

A larger exhibition, “Forrest Bess: Seeing Things Invisible,” will be presented at the Menil Collection in Houston next year, and will include the installation now at the Whitney. ↩