Jan Gross and Irena Grudzińska Gross conclude their account of grave robbery after the Holocaust with a story from the very recent past. A Polish businessman, returning from Berlin, narrowly escaped death in an automobile accident. The following night, a Jewish girl appeared to him in a dream, addressed him by his first name as if he were a friend or a child, and asked him to return her ring. The businessman did have a gold ring, given to him by his grandparents, who had lived near Bełżec, one of the major death factories built by the Germans in occupied Poland.

Hoping to save themselves or their families, Polish Jews on the death transports of 1942 sometimes exchanged the valuable objects they had managed to take with them for water (or promises of water) with local Poles when the trains stopped short of their destination. Anything that remained was seized when the Jews had to undress before being led to the gas chambers. Gold teeth were removed from the corpses by Jewish slave laborers, and taken by the Germans. Some valuable objects were hidden by the Jewish laborers and were then exchanged with the camp guards, who were often Soviet citizens taken prisoner by the Germans. They exchanged the objects for food, alcohol, and sex in nearby Polish villages. Some of the valuables remained at the site of the gas chambers when the Germans retreated. After the war, the locals would dig up the corpses looking for gold.

The businessman did return the ring, as best he could: he gave it, along with a note, to the museum at Bełżec. In some ways his gesture and his story reflect the realities of today’s Poland. Every detail of his account—the commercial relationship with Germans, the business trip by chauffeur-driven car, even the travel on good roads—bespeaks a Poland that is today more prosperous than ever in its history. Liberated in 1989 from the communism that followed German occupation, allied to the United States in NATO since 1999, linked to its neighbors in the European Union since 2004, Poland is a beneficiary of the globalization of the post-Communist years.

As Donald Bloxham suggests in his Final Solution, the Holocaust can be seen, among many other things, as the final catastrophe accompanying the breakdown of what some historians call the first globalization, the expansions of world trade of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It collapsed in three stages: World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II. Its fatal flaw was its dependence upon European empire. The process of decolonization began within Europe itself, as the Balkan nation-states liberated themselves first from the Ottoman Empire and then from the dominance of their British, German, Austrian, or Russian imperial patrons. The leaders of these small, isolated, agrarian nation-states found a natural harmony between nationalist ideology and their own desperate economic situations: if only we liberate our fellow nationals beyond the next river or mountain range from foreign rule, we can expand our narrow tax base with their farmland.

After a few false starts involving wars against one another, the Balkan nation-states turned against the Ottoman Empire itself in 1912 in the First Balkan War, effectively driving Ottoman power from Europe and dividing up the spoils (although not without a Second Balkan War, in 1913). The conflict that we remember as World War I can be seen as the Third Balkan War, as elements within the Serbian government tried to win territory from Austria just as they had recently done from the Ottomans. With the coming of World War I, the Balkan model of establishing nation-states spread to Turkey (which involved the mass murder of more than a million Armenians); afterward it was accepted in Central Europe. World War I also shattered a system of world trade, and inaugurated an era of European impoverishment that would last nearly half a century.

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian soldier fighting in that war, though in the German army. His anti-Semitic response to the defeat of Germany and Austria, articulated in Mein Kampf in 1925, is interpreted by Bloxham in The Final Solution as an intellectually spurious but politically powerful attempt to extract Germany from its fate as a defeated nation-state by restoring its imperial goals. The war itself had harmed the German homeland itself relatively little, since the country was never occupied. But Germany, which lost nearly 2.5 million dead in the war, was defeated, a brute fact that Hitler found inexplicable. If a reason for Germany’s defeat could be identified, then the program for Germany’s return to the center of world history could be realized.

Advertisement

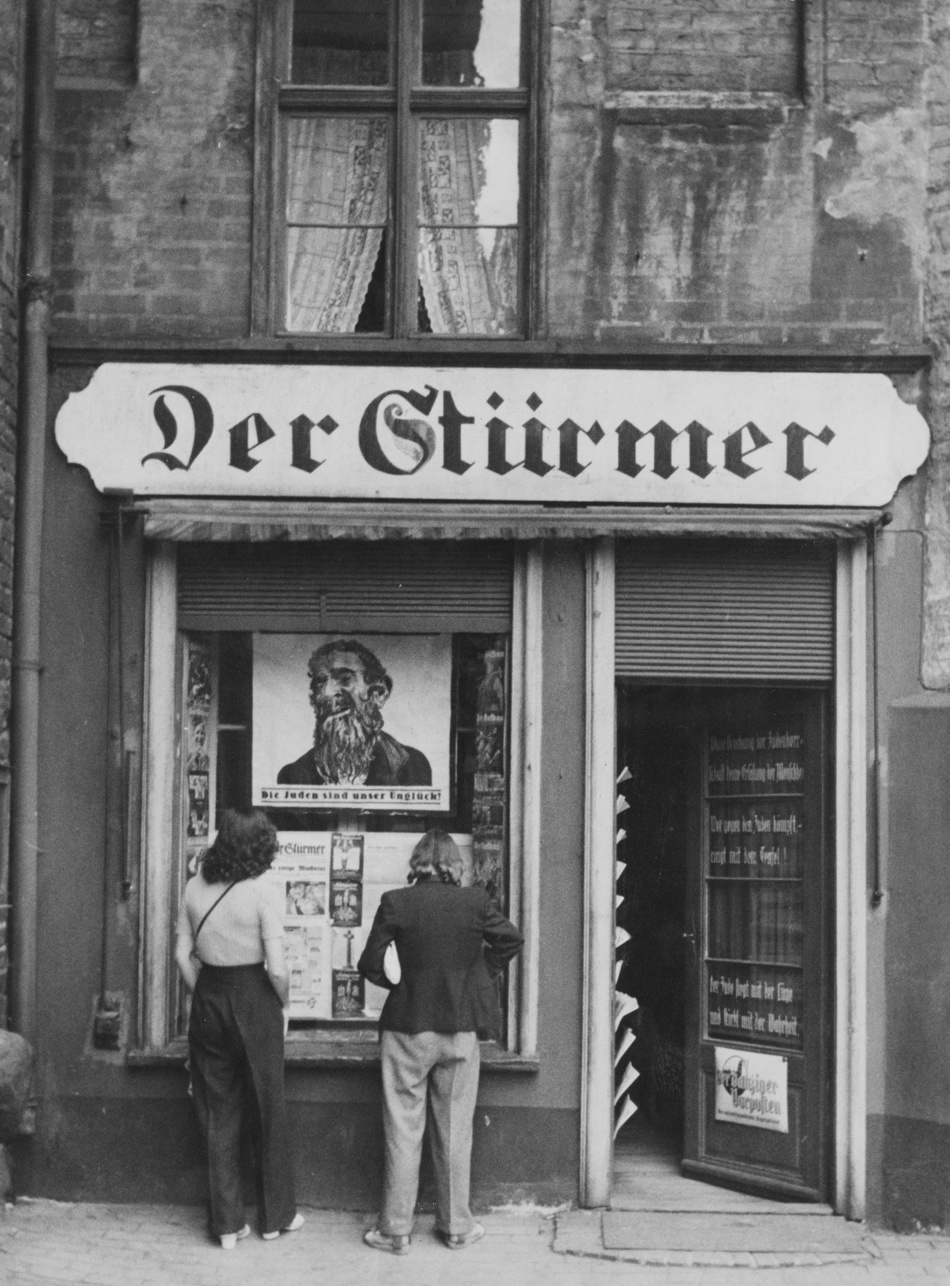

Hitler falsely held the Jews responsible not only for the defeat of 1918, but for the postwar settlement. In the West, Jews were supposedly the principal source of the heartless finance capitalism of London and New York that permitted the painful food blockade of Germany in 1918 and the hyperinflation of the early 1920s. In the East, Jews were supposedly responsible for the communism (“Judeobolshevism”) of the Soviet Union. Jews around the world were responsible, argued Hitler, for the false universalisms of liberalism and socialism that prevent Germans from seeing their special destiny.

Hitler’s program for German revival was, at one level, a simple reenactment of the Balkan combination of nationalism with agrarianism, which he had praised in Mein Kampf. Germany must fight with its neighbors for “living space” in the East to achieve agricultural self-sufficiency. Unlike the Balkan states, of course, Germany was a great power that could envision not just gains of territory but a new land empire, something it seemed to have achieved in Ukraine at the end of World War I. Hitler’s obsession with anti-Semitism made the vision global both in its symbolism and in its ambition: an invasion of the East would mean the occupation of the part of the world where most Jews lived, the destruction of the Soviet Union, and the achievement of world power.

To attempt to realize the program of Mein Kampf, Hitler needed to win power in Germany, to destroy Germany as a republic, and to fight a war against the USSR. As Edouard Husson notes in his book on Heinrich Himmler’s deputy Reinhard Heydrich, the Great Depression made it possible for Hitler to win elections and begin his transformation of Germany and the world. In Hitler’s Germany after 1933, the state was no longer a monopolist of violence, in Max Weber’s well-known definition. It became instead an entrepreneur of violence, using violence abroad—terror in the Soviet Union, assassinations of German officials by Jews—to justify the violence at home that was in fact organized by German institutions. Hitler then used the alleged threat of domestic instability to justify the creation of ever more repressive institutions.1

For most of the 1930s Hitler maintained the pose that his foreign policy was nothing more than the classic Balkan one, the gathering in of fellow nationals along with their land. This was the justification given for the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia and the annexation of Austria in 1938. But in fact, as Husson shows, the takeover of these countries and destruction of their governments was a trial run for a much larger program of racial colonization further east.

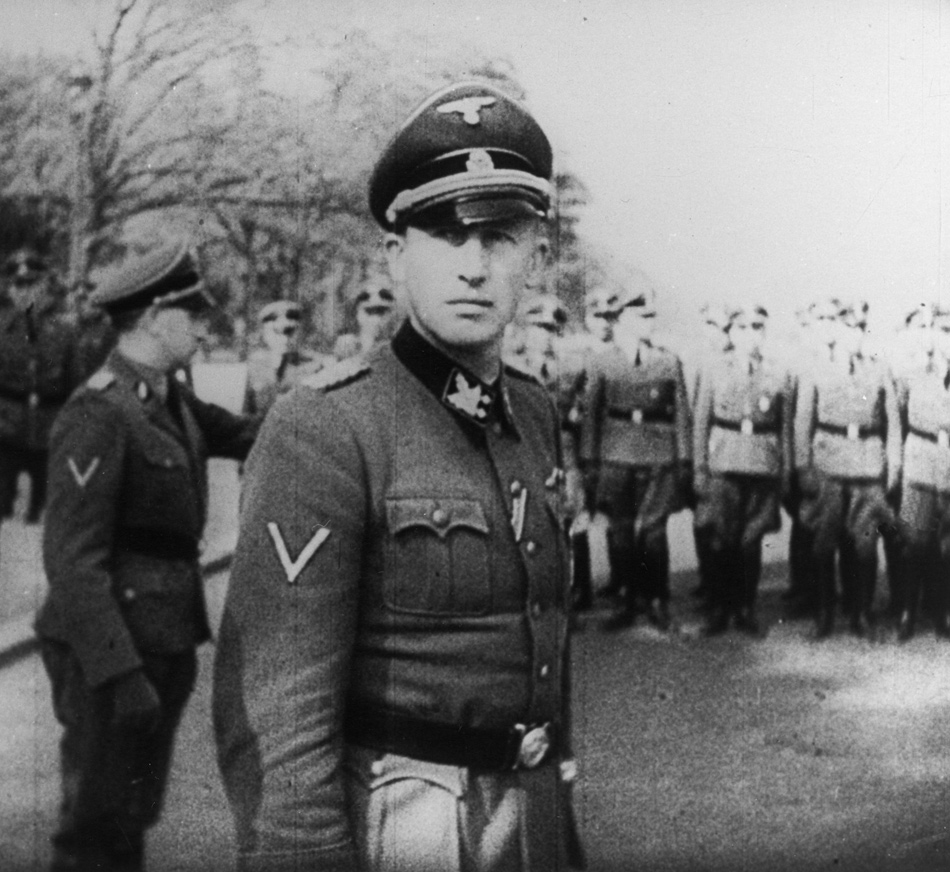

Husson’s method is to follow the career of Heydrich, the director of the internal intelligence service of the SS, and the ideal statesman of this new kind of state.2 The SS, an organ of the Nazi party, was meant to alter the character of the state. It penetrated central institutions, such as the police, imposing a social worldview on their legal functions. The remaking of Germany from within took years. Heydrich understood, as Husson shows, that the destruction of neighboring states permitted a much more rapid transformation. If all political institutions were destroyed and the previous legal order simply obliterated, Heydrich’s organizations could operate much more effectively.

In particular, the destruction of states permitted a much more radical approach to what the Nazis regarded as the Jewish “problem,” a policy that Heydrich was eager to claim as his own. In Germany, Jews were stripped of civil rights and put under pressure to emigrate. After Germany seized the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia in 1938, its Jews fled or were expelled. When Austria was incorporated into Germany, Heydrich’s subordinate Adolf Eichmann created there an office of “emigration” that quickly stripped Jews of their property as they fled anti-Semitic violence.

Historians tend to see World War II from two perspectives: one as the battlefield history of the campaigns by, and against, Germany; the other as the destruction of European Jews. As Hannah Arendt suggested long ago, these two stories are in fact one. Part of Hitler’s success lay in denigrating international institutions such as the League of Nations and persuading the other powers to allow his aggression in Czechoslovakia and Austria. As Bloxham stresses, the weakness of the Western powers meant that the fate of citizens, above all Jewish citizens, depended upon the actions (and existence) of states. The Evian Conference of 1938 demonstrated that no important state wanted to take Europe’s Jews.

Hitler, as Husson observes, apparently believed that, in the absence of American willingness to accept European Jews, European powers should ship them to Madagascar. The island was being considered as a place for Jews by Polish authorities at the time, though as a possible site for a voluntary rather than involuntary emigration. Husson writes that Hitler seemed to believe until early 1939 that Germany and Poland could cooperate in some sort of forced deportation to the island. Poland lay between Germany and the Soviet Union, and was home to three million Jews, more than ten times as many as Germany. Hitler, who wished to recruit Poland into a common anti-Communist crusade, presumably imagined that this deportation would take place during a joint German and Polish invasion of the Soviet Union.

Advertisement

Because Poland refused any alliance with Nazi Germany in the spring of 1939, Hitler made a temporary alliance with the Soviet Union against Poland. The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 sealed the fate of the Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, and Polish nation-states, and it was particularly significant for their Jewish citizens. The joint invasion of Poland by both German and Soviet forces in September 1939 meant that Poland, rather than becoming some sort of junior partner to Nazi Germany, was destroyed as a political entity. Unlike Austria and Czechoslovakia, Poland fought the Germans, but it was defeated. Poland therefore offered a new opportunity for Heydrich, because its armed resistance created the possibility to initiate mass murder under cover of war.

Heydrich’s Einsatzgruppen were ordered to destroy the educated Polish population. Poland was now to be removed from the map, its society politically decapitated. The destruction of the Polish state and the murder of tens of thousands of Polish elites in 1939 did not destroy Polish political life or end Polish resistance. Auschwitz, established in 1940 as a concentration camp for Poles, also failed in this regard. The Germans murdered at least one million non-Jewish Poles during the occupation, but Polish resistance continued and in fact grew.

Nor did the destruction of the Polish state provide an obvious way to resolve what Hitler and Heydrich saw as the Jewish “problem.” At first Heydrich wanted a “Jewish reservation” established in occupied Poland, but this would have done no more than move Jews from some parts of the German empire to others. In early 1940 Heydrich’s subordinate Eichmann asked the Soviets—still German allies—if they would take two million Polish Jews; this was predictably refused. In the summer of 1940, after Germany had defeated France, Hitler, the German Foreign Office, and Heydrich returned to the idea of a deportation to Madagascar, a French colonial possession. Hitler wrongly assumed that Great Britain would make peace, and allow the Germans to carry out maritime deportations of Jews.

The Final Solution as applied to Poland’s Jews would thus take place in Poland, but it was still not clear, as 1940 came to an end, just what it would be. As Andrea Löw and Markus Roth remind us in their fine study of Jewish life and death in Kraków, Polish Jews were not simply impersonal objects of an evolving German policy of destruction. Kraków’s Jews, like those of Poland generally, had been organized under Polish law into a local commune (kehilla or gmina) that enjoyed collective rights. It was this institution that the Germans perverted by the establishment of the Judenräte, or Jewish councils responsible for carrying out German orders. Despite a few anti-Semitic laws in the late 1930s, Poland’s Jews were equal citizens of the republic.

When the republic was destroyed, German anti-Semitic legislation could immediately be imposed. German expulsions of Jews from their homes, which would have been an unthinkable violation of property rights in Poland, demonstrated that Jewish property was for the taking. The Germans themselves seized bank accounts, automobiles, and even bicycles. Pending some future deportation, the Jews of Kraków were held in a ghetto where they suffered from lawlessness, exploitation, misery, and death from disease and hunger. But this was not yet a Holocaust.

The German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941 was meant to be the fulfillment of Hitler’s great imperial plans. In fact, German power reached far enough east to control the major lands of Jewish settlement in Europe, but not far enough to reach Moscow or destroy the Soviet Union. At the very beginning of the invasion, German forces conquered lands that had already been conquered by the Soviets during the same war, and drove out the Soviet occupation regime.

It was in this zone of double destruction of the state that the Germans began, for the first time, to organize the killing of Jews in large numbers. In entering eastern Poland, which had been annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939, the Germans encouraged local attacks on Jews by Poles. The most notorious example, in the town of Jedwabne, was described by Jan Gross in an earlier book.3 In the Baltics, where the Soviet Union had destroyed three independent states in 1940, local support for German policies was easier to organize. Lithuania was especially significant, since it was a state destroyed by the Soviets that was also home to a large number of Jews. In entering Lithuania in summer 1941, the Germans were destroying a Soviet political order that had itself just destroyed the Lithuanian state.

In doubly-occupied Lithuania, German entrepreneurs of violence such as Heydrich had far greater resources and far greater room for maneuver than in Germany or even Poland. The Einsatzgruppen, which in occupied Poland had chiefly killed Poles, in occupied Lithuania chiefly killed Jews. A provisional Lithuanian government, composed of the Lithuanian extreme right, introduced its own anti-Semitic legislation and carried out its own policies of murdering Jews, explaining to Lithuanians that Bolshevik rule had been the fault of local Jews, and that destroying them would restore Lithuanian authority.

This was a German policy implemented in considerable measure by Lithuanians, but it could not possibly have worked without the prior destruction, occupation, and annexation of the Lithuanian state by the invading Soviet Union. A considerable number of the Lithuanians who killed Jews had just been collaborating with the Soviet regime. After the Germans abolished the provisional Lithuanian government and imposed direct rule, the scale of the violence increased substantially, now with no central political Lithuanian authorities but with the cooperation of Lithuanian policemen and militiamen.

As Christoph Dieckmann writes in his landmark study, the “Lithuanian countryside was transformed in the second half of 1941 into a giant graveyard of the Lithuanian Jews.” By his reckoning, some 150,000 Jews were murdered in Lithuania by November 1941. It is suggestive, as Husson notes, that both Heydrich and his immediate superior Heinrich Himmler visited the Baltics in September 1941, right before a series of meetings with Hitler. Bloxham agrees that for Hitler’s regime, early local collaboration in the mass murder of Jews “signaled what was possible.” Deporting Jews had proven to be impossible. What was possible was murdering them where they lived. This was a Holocaust.

There can be no doubt that Hitler’s policy was to eliminate Jews from all lands under German control. But for most of his rule, from 1933 through 1941, he had no plausible way to remove them. It was only in the summer of 1941, eight years after seizing power, three years after his first territorial enlargement, two years after beginning a war, that Hitler could envision ways to carry out a Final Solution. The method that proved workable, mass murder, was developed in a zone where first the Soviets had destroyed independent states and then the Germans had destroyed Soviet institutions.

Then the Holocaust spread quickly, and with almost equal force, into the places where the state was destroyed only once: eastward into the lands of the pre-war Soviet Union, where German power replaced Soviet power and Jews were killed by bullets, and westward into occupied Poland, where most of the killing was by gassing. Gassing facilities such as Bełżec were built, and gas chambers were added to the Auschwitz camp complex. In the Soviet Union non-Germans were needed to carry out the mass shooting, and Soviet citizens were willing to take part; in Poland the Jews killed in the gas chambers were those who had already been forced into ghettos, and could thus be killed more systematically.

The Holocaust was less comprehensive where Hitler’s intentions encountered the rule of law, no matter how attenuated or perverted. The German ally Slovakia at first deported its Jews to Auschwitz, although it later reversed that policy. In the Netherlands, which were under German direct rule, three quarters of the Jews were murdered. Independent Bulgaria, Italy, Hungary, and Romania, although German allies, generally did not follow German policy, and the Italian army saved a considerable number of Jews. Romania had its own policy of killing Jews, which it reversed in 1942. Hungary did not send its Jews to German death camps until invaded by Germany itself. In Nazi Germany itself about half of the Jews alive in 1933 died a natural death. The Germans almost never killed Jews who were British subjects or American citizens, even when they might easily have done so.

Nazi Germany was a special kind of state, determined not to monopolize but to mobilize violence. The Holocaust was not only a result of the determined application of force but also of the deliberate and practiced manipulation of institutions severed from destroyed states and of social conflicts exacerbated by war. As Jan Gross is careful to stress, the deportation to the death facilities was the “main disaster” that befell Poland’s Jews, and it came “at the hands of the Germans.” But what of the quarter-million or so Polish Jews who somehow escaped the gassing, and who sought help among Poles in 1943, 1944, and 1945? Gross, along with Jan Grabowski and Barbara Engelking, records the undeniable fact that most of these people were murdered as well, perhaps half of them by Poles (following German policy and law) rather than by Germans.

Together, these Polish historians make two essential arguments that help us to understand the workings of deliberate Nazi persecution after the destruction of the Polish state. One is the continuity of personnel and of obedience. In general the Polish police continued to function, now taking orders from the Germans. Whereas in 1938 their job included preventing pogroms in independent Poland, in 1942 they were ordered to hunt down Jews. Second, local governments could be mobilized to capture Jews who had escaped the gas chambers. Poles in a given area were named as hostages, to be punished if a hunt for Jews failed. Local leaders were personally responsible for keeping their districts free of Jews, and could easily be denounced if they failed to do so. In the event of a successful hunt for Jews, local leaders were responsible for the distribution of Jewish property.4

Peasants in the countryside, as Engelking and Grabowski demonstrate, were unconcerned with protecting the reputation of the Polish nation (with which they likely did not identify), but obsessed with their position relative to their neighbors.5 Peasants figure in all of these books as competitive, jealous, and concerned above all with property. Under German occupation, peasants regularly denounced one another to the Germans on all conceivable pretexts. This “epidemic of denunciations,” as Grabowski puts it, made the prospect of rescuing a Jew from the German policy of destruction extremely difficult. Peasants noticed when a neighboring family was collecting more food, keeping different hours, or even bringing home a newspaper. All of these were signs that a Jew was being hidden, and led to denunciations which had overlapping motives: desire for the property of the Jews and those hiding them, and fear of collective German reprisals.

In this situation, as Engelking observes, it was highly irrational for Polish peasants to help Jews: “in the case of Jews seeking aid the costs of refusing them were zero, and the costs of helping them were enormous.” As she and Grabowski both show, very often Poles acted as if they were rescuers, took the Jews’ money, and then turned them in to the police. In Grabowski’s study of dozens of cases of rescue and betrayal, he found that the Jews who were rescued rather than betrayed were precisely those who found their way to people who were not thinking of personal gain. This also holds of course for Poles such as Jan Karski and Witold Pilecki who voluntarily entered, respectively, the Warsaw ghetto and Auschwitz.6 As Grabowski is careful to stress, there were such people in the county he investigates, and throughout occupied Poland. Engelking recalls Wacław Szpura, who baked bread three times every night for the thirty-two Jews he rescued.

To be sure, Nazi official anti-Semitism created incentives in the regions in which this last painful episode of the Holocaust took place. Popular anti-Semitism made it less likely that Poles saw their Jewish neighbors as people about whom they should have concerns, and more likely that they would fear denunciation by their neighbors.7 The ethical obsession of all three Polish historians under review is the undeniable reality that Poles often brought about the death of Jews when they might instead have simply done nothing. But we have many reasons to doubt that only anti-Semites killed Jews.

For one thing, action is no simple guide to ideology. Grabowski concludes, from careful study of individual cases in one region, that Poles who murdered Jews were more likely to join the communist party that ruled Poland after the war. This confirms a suggestion that Gross made more than a decade ago: that people who collaborate with one occupation are likely to collaborate with the next. The frequency of double collaboration, a natural corollary of double occupation, forces us to restrain our tendency to explain violence by ideological conviction. The Poles who appear on the cover photograph of Gross’s Golden Harvest, digging for gold at Treblinka, are continuing, as communism arrives, the theft that was endorsed by German policy. The Polish communist regime, on a far larger scale, also continued this process, nationalizing the formerly Jewish businesses and property that the German occupation regime had seized from Jews that it murdered.

Poland’s communist regime, in power for more than forty years, concocted a myth of the Holocaust in two stages: first portraying (falsely) Poles and Jews as equal victims, then suggesting (anti-Semitically) that passive Jews should be grateful to the heroic Poles who tried to rescue them from their own helplessness. This line was taken in 1968, when the communist regime expelled several thousand of its citizens, among them Jan Gross and Irena Grudzińska, on the spurious charge of “Zionism.” The work of Gross, Grabowski, Engelking, and other Polish historians is, inevitably, a response to the myths of the Communist era, which are still convenient for some Polish nationalists of today, as well as an attempt to reestablish the Holocaust as a central part of Polish history.8

In the last decade many pioneering studies of the Holocaust have appeared in the Polish language. This reflects a genuine and impressive attempt to address the real trauma in the Polish past. It is no denigration of the courage and intelligence of Polish historians to note that it also reflects the security of an independent Poland anchored in international institutions and prosperous within the global economy. If we understand the Holocaust as, among many other things, the worst consequence of the collapse of the first globalization, we might see its civil and considered discussion as one of the achievements of a second globalization, our own. In such a world a ring might be returned, but such a world is a fragile thing.

-

1

For the economic version of this argument, see Adam Tooze, The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy (Viking, 2007). ↩

-

2

For an excellent recent biography of Heydrich, see Robert Gerwarth, Hitler’s Hangman: The Life of Heydrich (Yale University Press, 2011), reviewed in these pages by Max Hastings (The New York Review, February 9, 2012). ↩

-

3

Jan Gross, Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland (Princeton University Press, 2001); see also Wokół Jedwabnego, two volumes, edited by Paweł Machcewicz and Krzysztof Persak (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2002). ↩

-

4

These books complement Christopher Browning’s classic Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (HarperPerennial, 1998), which accurately portrays the German police as the guiding force in the hunts for Jews, but which does not consider local institutions in any detail. ↩

-

5

The sociology of betrayal and rescue in the cities was different: see Gunnar S. Paulsson, Secret City: The Hidden Jews of Warsaw, 1940–1945 (Yale University Press, 2002). ↩

-

6

Their reports are published: Karski’s Story of a Secret State: My Report to the World (London: Penguin, 2011); and Pilecki’s The Auschwitz Volunteer: Beyond Bravery, translated by Jarek Garliński (Aquila Polonica, 2012). ↩

-

7

Brian Porter-Szücs devotes an important chapter to this subject in his Faith and Fatherland: Catholicism, Modernity, and Poland (Oxford University Press, 2011). A recent profound study of the reorientation of Catholic theology regarding Jews is John Connelly, From Enemy to Brother: The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews (Harvard University Press, 2012). ↩

-

8

For an explicit attempt to address certain Communist-era myths, see Dariusz Libionka and Laurence Weinbaum, Bohaterowie, hochsztaplerzy, opisywacze: Wokól Zydowskiego Zwiazku Wojskowego (Heroes, swindlers, storytellers: On the Jewish Military Association) (Warsaw: Stowarzyszenie Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów, 2011); see also Mikołaj Kunicki, Between the Brown and the Red: Nationalism, Catholicism, and Communism in Twentieth-Century Poland (Ohio University Press, 2012). ↩