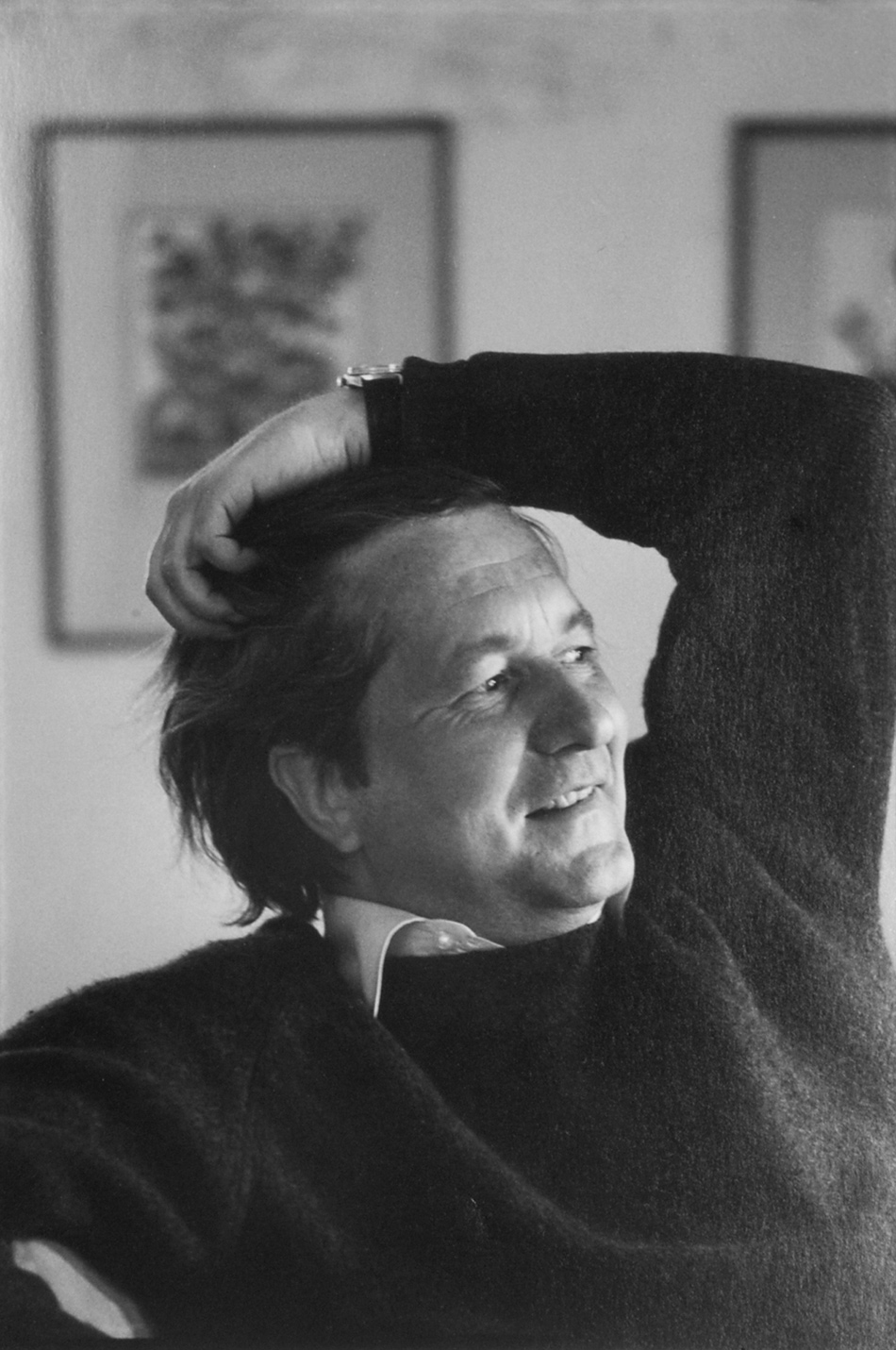

The hundreds of letters written by William Styron, nearly sixty years of them, many quite long, are about such matters as the public apology of Robert McNamara regarding the Vietnam War, capital punishment, the crassness of American culture, politicians, publishers, the books of friends and less-known writers, the ignorance of critics. There are letters of considered opinion and those of a good old boy, the vulgarities included. In them are marvelous images: William Burroughs, met in Paris,

is an absolutely astonishing personage, with the grim mad face of Savonarola and a hideously tailored 1925 shit-colored overcoat and scarf to match and a gray fedora pulled down tight around his ears. He reminded me of nothing so much as a mean old Lesbian and is a fantastic reactionary, very prim and tight-lipped and proper who spoke of our present Republican administration as that “dirty group of Reds.”

Styron, during his long and distinguished career as a writer, produced four novels, or five counting the novella The Long March (1956). He wrote slowly in longhand on yellow pads, usually in the afternoon, not going on to the next paragraph or page until he was satisfied with what he had written before. He complained always of the difficulty of writing, the torture of it. “Writing for me is the hardest thing in the world.” He loathed it, he said, every word that he put down seemed to be sheer pain, yet it was the only thing that made him happy.

From youth his sole and burning ambition was to be a writer. For him there was never any question but that it was manly and important work. His father, who was an engineer in the shipyard in Newport News, Virginia, and to whom Styron was always close, encouraged him in this. Styron’s mother died when he was nine years old and he grew up with a stepmother who was not a large influence on his life. The early letters to his father frequently mention the writing he is doing, at college and afterward, describing and discussing it. Styron was idealistic, open, and committed to truth, not just the objective truth but the truth that lies in the heart and that everyone recognizes.

Styron was born in Newport News in 1925 and the family later moved to a small, somewhat rural village about ten miles away. He was a true southerner, from the Tidewater country of Virginia, and though he resisted being classed as a southern writer, his novels are largely southern—Lie Down in Darkness (1951), The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967)—and it is a southern narrator, Stingo, the voice of Styron himself, who tells the story of Sophie in Sophie’s Choice (1979). He wrote long. Length and amplitude, he felt, were primary virtues of the novel. “My natural bent seems to be rhetorical,” he wrote to his teacher at Duke, William Blackburn. “I believe that a writer should accommodate language to his own peculiar personality, and mine wants to use great words, evocative words, when the situation demands them.”

Lie Down in Darkness, his first novel, was begun with the encouragement of Blackburn and also of Hiram Haydn, then an editor at Crown who had Styron as a student in a writing class he was teaching at the New School. It took almost four years to write and was completed in 1951, just before Styron was called back into the Marines during the Korean War. He had been in the Marine V-12 program at Duke, and had completed training and gone on to officers’ school and been commissioned a second lieutenant. He was stationed at Quantico, destined to be part of the Marine force that would invade Japan, when the war ended.

Lie Down in Darkness was published to some acclaim in September 1951. He wrote to William Blackburn:

The reviews, most of them, have been quite wonderful. You probably saw the Sunday Times and Tribune. The out-of-town reviews have practically all been superlative, with the exception of the Chicago Tribune, which said I needed an editor like Maxwell Perkins.

The novel’s length—four hundred pages—and density were two of its strengths, however, and it was awarded the Rome Prize by the American Academy of Arts and Letters. The judges included Malcolm Cowley, Allen Tate, Van Wyck Brooks, and W.H. Auden, and the prize included a year in Rome and a stipend of $3,500. In March 1952 Styron sailed for Europe on the Île de France. On board were Lena Horne and Arthur Laurents, with whom he wrote that he got plastered in the First Class bar.

It was the rising of the curtain. In Europe, first in London and then in Paris where he stayed for five months, and finally in Rome, he saw the great world. He met Peter Matthiessen and the Paris Review crowd in Paris. The magazine was just getting started and he became part of it. He met and became friends with Irwin Shaw. He was in Rome less than a month when he met again a beautiful American girl, Rose Burgunder, whom he had been introduced to at Johns Hopkins a year earlier. She left a note in his mailbox and they got together at the bar of the Excelsior Hotel for a drink. Six months later they married.

Advertisement

In Paris Styron had written a long story based on an incident he experienced in the Marines, which would later appear in book form as The Long March. It was published in 1953 in the magazine Discovery, and not long after, a letter from Norman Mailer reached him in Rome saying that it was “as good an eighty pages as any American has written since the war.” Mailer was the contemporary Styron admired most, and he promptly replied with his own letter of friendship and flattery, praising The Naked and the Dead (1948) and Barbary Shore (1951). A long correspondence of mutual admiration and approval followed, two young lions licking one another’s paws—James Jones, who had written From Here to Eternity (1951), was a third. Saul Bellow was a decade their senior, John Cheever was a New Yorker writer, Philip Roth was in high school, Isaac Singer was another world.

Some months later Styron, as his good friend, wrote to Mailer about The Deer Park (1955), a Hollywood novel:

First of all, I think it’s a fine, big book in the sense that it’s a major attempt to re-create a distinct milieu—an important one and one deeply representative of all the shabby materialism and corruption which are, after all, the real roots of our national existence. As a picture of this milieu, the book seems to me to be both honest and brilliant. It is also a depressing book, really depressing, in its manifest candor, and I’m afraid there aren’t going to be many people who will like it.

Perhaps to smooth things over, in a following letter Styron wrote:

Parts of The Deer Park still keep coming back to me. It’s amazing how solid a book it is, in the sense that its effect hangs on, even if you don’t particularly want it to. I think this is because there is in the book an unremitting determination to be truthful, and that beautifully distinguishes it from most of the novels which are coming out these days, the writers of which have become so bewilderingly entangled in the dishonesty and million-dollar-hokum of contemporary American life that they’ve lost their point of view entirely, so that their slickly cynical distortions are accepted as realism and truth. Most every form of expression in America is now keenly attuned to the second-rate, if not third-rate….

In the fall of 1954, following their return from Europe, Styron and his wife bought an old house and eleven acres in Roxbury, Connecticut, where they lived from then on, eventually with their four children. They later bought a second house on Martha’s Vineyard where they spent long summers. Styron wrote to Mailer that fall:

Since you heard from me I have finally come to the point where I think I can hazard the statement that my next novel is under way. I never thought that a project could be so hellishly difficult or seem to stretch out so aimlessly and vainly toward the farthest limits of the future, but I am embarked, at least…. I remember your once asking me if it was to be a “major effort”; I don’t know what I said in reply, only now I’m beginning to realize that it is a major effort—major in the sense that it has become impossible for me to write anything without making it a supreme try at a supreme expression.

The Mailers moved to Connecticut themselves two years later, and the couples often saw each other socially. The next letter came as a thunderclap. It was Mailer’s accusation that he had heard that Styron had been passing “atrocious remarks” about Mailer’s wife, Adele, and invited Styron to a fight “in which I expect to stomp out of you a fat amount of your yellow and treacherous shit.” In a second letter, Mailer invited Styron to repeat an explanation face-to-face. That never happened. It was more than twenty years before they corresponded again. Styron told James Jones that it was Rose’s theory that it was Mailer’s pent-up homosexuality focused on Jones that caused him to become insanely jealous, hence the venomous letter:

This is awful stuff to talk about, but we are dealing with a lunatic. At any rate I’m convinced that this jealousy, combined with a bitter envy of both of our talents, has been at the root of his hatred.

At the beginning of 1960, Styron wrote a long letter to Robert Brown, an editor at Esquire, which had published a section of the new novel, Set This House on Fire, explaining his history and that of Lie Down in Darkness:

Advertisement

It came out in 1951, and due to the good offices of an editor and publisher who had faith in the book it received considerable journalistic attention. It got fine reviews in the Sunday book pages; embarrassingly enough, even Prescott half-liked it, and though Time Magazine and The New Yorker shrugged it off as another magnolia-and-moonlight potboiler, there were a lot of very fine and intelligent reviews from the provinces. It was even a moderate best-seller for a while, and then it dropped out of sight. Well, I thought all this was swell enough, but being university-bred myself and not ashamed of it I began to wonder when I would get really serious attention. I mean I began to say to myself that all this middlebrow attention was very good, but now—how about the serious audience? How about the old Kenyon and old Partisan and the old Hudson and all the rest? Who was going to tout this book onto the college readers—the serious young people in college or just out who after all make up one of the major parts of a serious writer’s audience?

By “serious,” Styron did not mean something “slim and jazzy” by John Updike, or something of Mary McCarthy’s, or Peter Taylor’s, or even worse, James Michener or the “talentless, self-promoting” Gore Vidal. He meant one of his own books, or Mailer’s, or James Jones’s, with whom he allied himself in the desire to be honored and recognized. He wanted a critic like Edmund Wilson or H.L. Mencken to acclaim him, but there was none to be found:

If, as I believe to be true, one of the important functions of criticism is not only to explicate the whiteness of Melville’s whale but also to apprehend and pay serious attention to the literature of one’s own time, then I personally feel that I do not owe to contemporary criticism a plug farthing. I think that contemporary literature is blighted not so much by the Prescotts and J. Donald Assholes (though they are bad enough) but by the cliquishness and myopia of the Trillings and the Chases and the deadly young squirts like Podhoretz and such actual haters of books as Leslie Fiedler, who wish the novel to be dead.

Lionel Trilling was a champion of Saul Bellow, who was always an annoyance to Styron. The Adventures of Augie March (1953) had bored him; articles he read praising Bellow he dismissed as blowjobs. There was a nationwide poll of critics in 1965 on the great writing of the previous twenty years. Lie Down in Darkness was on the list, “12th Greatest—not too bad out of the many thousands,” Styron boasted to Bob Loomis, his editor and close friend, except that on the list of twenty there were four of Bellow’s books.

Styron’s habit as a writer was to sleep late and lie in bed for an hour in the morning reading and thinking. He had a walk before sitting down to work in the afternoon and into the evening when he would put on classical music, drink, and have dinner at nine. Often he read aloud to his wife the pages he had written that day, and he discussed chapters he was working on with her and with Loomis. Drink is mentioned frequently in the letters and was an important part of his life. When working, Styron was a solid machine. Rose took care of the children, the house, and an increasingly active social life.

Set This House on Fire (1960), his second novel, set in Italy, was not well received except in France, where it was a runaway success, the biggest since the war, and Styron became widely known. In America it was almost the opposite. His reputation was damaged. The book had proved the falsity of his promise as a writer, the New York Times critic wrote, and the verdict in The New Yorker, a magazine Styron regarded with scorn all his life, was equally bad.

In a letter to the critic Maxwell Geismar, who for a long time was his ardent supporter, he wrote:

It turns out that Mailer is a false prophet. He said that I wrote a phony big book and that I would be “made” in the mass media the most important writer of my generation. In reality, I wrote just what he shuddered to think I would do—a true book—and now I shall have to become the most important writer by the hard route—by living down all the cheap but powerful Time–New Yorker shit, and by having S.T.H.O.F. achieve its reputation in the same way “Darkness” did—slowly but steadily and with the immeasurable help of M. Geismar.

For a long time Styron had been interested in writing about a bloody and little-known slave uprising in Virginia in 1831, led by a slave named Nat Turner, and he conceived the idea of writing about it from Nat Turner’s point of view. It was a subject that had been on his mind, set in a place he knew and in a society he understood, that was his heritage. He had grandfathers and uncles on both the Union and Confederate sides during the Civil War. His grandmother used to tell him about the two little slave girls that she herself had owned as a little girl and how much she loved them. In a letter to Robert Penn Warren, he wrote:

As a boy I spent much time with this old grandmother of mine. Mainly during the summers I spent much time amid the small-town life of the Tidewater Va. and N.C. region, having all sorts of cousins spread about there. I went to a rural high school about ten miles up the James River from Newport News at a time when there was still a rural atmosphere in the area. I never actually lived on a farm or anything like that (I was raised in a village) but there was still enough real country around for me to get a lot of it in my bones.

Styron worked on the book for nearly four years, at one point encouraged by a psychiatrist friend of Lillian Hellman’s, who observed that the years between forty and fifty were the most productive in a man’s life. Styron was just about to turn forty at the time. He felt in perfect control of what he was writing, a combination of what was historically true, the details of the rebellion and gruesome massacre, and the imagined character and soul of the black man who led it. Where the idea of writing it from the slave’s point of view came from, he was not certain. Few if any books by white men had been written from a black viewpoint, he later observed, and maybe this fact caused him to risk it.

The Confessions of Nat Turner set everything right. Random House had gotten behind the book. The reviews were extensive and excellent; it won the Pulitzer Prize. The problem with Lie Down in Darkness, Styron once judged, was that it hadn’t been attuned to the zeitgeist and despite its merits had not had a solid apprehension of the present in relation to the past. In the era of civil rights and emergent black consciousness, when race was at the forefront of American awareness, Nat Turner caught the zeitgeist. In six weeks it sold 100,000 copies and went to the top of the best-seller list. Martin Luther King read and admired it, but there was also fierce criticism from intellectual and influential blacks who condemned it as racist, distorted, perpetuating a cliché image of blacks, and appropriating their history. A book, Nat Turner: Ten Black Writers Respond, appeared. The controversy was to go on for a long time. Styron defended himself vigorously and ridiculed the attacks—they utterly failed to understand the purpose of literature. He gave not an inch. At the end of the year he could write slyly in a postscript to a friend, “‘Nat’ has just hit 115,000—all white customers.”

At the beginning of 1973, Styron abandoned work on the novel about Marines that he had been struggling with—he would eventually return to it in the 1980s but never finish it—and began writing a manuscript entitled Sophie’s Choice: A Memory. Twenty-four years earlier he had met an Auschwitz survivor named Sophie who was living in the same rooming house that he was in Brooklyn. He knew her only for a few weeks and in fact never knew her last name or what became of her, but he was to make her into an imperishable figure.

In one of a number of letters he wrote to his oldest daughter, Susanna, when she was seventeen and gone off to school in Lugano—loving, newsy, and sometimes philosophical letters—he said:

Sophie is coming along well though as usual slowly and painfully. Along with its blessings, the wretched and insufferable part about “the Novel” is this dimension of Time—the sheer months and years it takes to get the thing finished. But I’m moving along with some sense of progress. I read some of it out loud to Bob Loomis and Hilary last week-end and I think they liked it a lot. It is so terribly weird to dare do what I am doing. I’m the only American writer (that is, writer as a member of my identifiable literary generation) who has faced the Holocaust head-on, the Concentration Camps, and I have made the amazing decision to embody the victim as a non-Jew. Certainly the hell I went through about Nat Turner will be a serene summer outing to what I will get for Sophie, or because of it. But I can’t go back. I’m committed like a bird in flight or a Boeing 747 in take-off and can’t go back! I have such an intense love-hate relationship with this work. Sometimes I can’t bear facing the pages, other times I feel it will be as good as anything written by anyone in this or any other decade.

When he finished writing it in 1979, it had taken him six years. It was a big novel in every sense, long, sentimental, tragic, vulgar, sexy, and finally utterly heartbreaking. Ted Kennedy called to read aloud the editorial in The Washington Star. There were bad reviews as well, but the reviews hardly mattered. The paperback sale was for $1,575,000 and in less than a year 225,000 copies had been sold; and the book won the inaugural American Book Award for fiction.

There was now no question of his prominence. Some of the voices raised against the book, including that of Cynthia Ozick objected, as Styron expected, to a non-Jew being the image of the millions of Jews murdered in the camps. Styron never relented. The movie of Sophie’s Choice was a triumph and Meryl Streep as Sophie was staggering and won the Oscar. In an exchange of letters with a man named Ben Crovets, who suggested that he, too, had known the original Sophie in Brooklyn, Styron speculated on whether she might see the movie and surface—she would have only been in her fifties—but nothing was ever heard of her.

Styron resumed work on his novel about the Marines. He had an ambivalent relationship with them all his life. He was writing about the apprehension he felt when he was waiting to be part of the invasion of Japan, and the moral question of whether the dropping of the A-Bomb was justified. His life was filled with the obligations of being an important writer, friendships, travel, his family. Because of some metabolic or chemical change that caused a reaction to it, he had stopped drinking. There were various physical problems about which he was open in letters to friends, but not about the depression he was experiencing. In 1985, at the end of the year, he was admitted to the Yale–New Haven Hospital because of suicidal depression. He wrote a brief letter to his close friend Peter Matthiessen:

Dear Peter,

I’ve gone through a rough time. I hope you’ll remember me with love and tenderness. I wish I’d taken your way to peace and goodness. Please remember me with a little of that zen goodness, too. I’ve always loved you and Maria.

Depression was a horrible sickness that destroyed a person. It destroyed sleep, appetite, libido, even intellect. The only merciful thing was that it almost always lessened and went away. Styron was in the hospital under treatment for nearly seven weeks. After he had recovered, he spoke about the experience and wrote an article about it for Vanity Fair that was widely reproduced and was the basis for his book Darkness Visible (1990), which found a large audience.

Through the 1990s there are fewer letters, many of them to Willie Morris, to whom Styron had become close after James Jones died. In the spring of 2000, however, the depression returned. It was even more serious. He asked a friend in desperation if he could obtain a suicide cocktail for him. He went into the hospital again, this time for six months. His health deteriorated. He had a series of strokes and also cancer. He was hospitalized for much of the last year and a half of his life and died in the hospital on Martha’s Vineyard in 2006.

In the letters there is the unforgettable night of the Nobel Prize winners’ dinner at the White House in 1962. Styron and Rose had never met JFK and Jackie but were invited to come upstairs afterward to a private gathering, and they became friends. There are letters about Styron’s play, about Arthur Miller’s, letters of the Vineyard summers, Frank Sinatra’s yacht, the Clintons. Styron never sought the limelight but it played on him anyway. He was a person of conviction regarding what was good and what was not in the world and also in literature, especially the novel. He became what he always dreamed and worked for, a writer, a famous writer. He had never considered anything else.

This Issue

January 10, 2013

Joy

Occupy the Rockaways!

How He Got It Right