Like astronomy, ornithology is a science to which amateurs have made authentic contributions. Today, however, the divide between amateurs and professionals in ornithology appears to be deepening, as the professionals revolutionize our understanding of the ornithological family tree and of bird behavior by employing cellular biology and the chemistry of DNA.

Tim Birkhead, professor of behavioral ecology at the University of Sheffield, in Britain, has a remarkable capacity to bridge that gap. Author of highly respected technical work on the social and sexual behavior of animals, Birkhead is also capable of making his and others’ research clear, and even inviting. His skill lies in the way he poses his questions.

Birkhead worked that vein brilliantly in an earlier book, The Wisdom of Birds.

1 His subject was, more precisely, people’s wisdom about birds—a historical account of how humans have understood the actions and behavior of birds. But whereas most histories of ornithology have proceeded person by person, Birkhead worked concept by concept. Some concepts—migration, for example—are very old. Aristotle discussed it at length. Other concepts—such as territory—have come into focus only recently. Birkhead traced each concept back to its initial formulation, sometimes a very long time ago, and then followed successive refinements over time, some of them very recent.

The most effective pioneers, Birkhead found, were not always the famous names. Scientists missed some fundamental matters by relying too much on logic and prior authorities and not enough on observation, while hands-on bird keepers made decisive discoveries about such matters as territorial conflict, the seasonal character of birds’ sexual activity, and “migratory restlessness”—the agitation displayed by caged migratory birds when the lengthening (or shortening) day shows that it is time to travel.

Now Birkhead’s Bird Sense asks another intriguing question: How do birds perceive their universe? What does the world look like to a bird? He starts with Thomas Nagel’s 1974 article, “What Is It Like to Be a Bat?” But whereas Nagel concluded that we cannot know what it feels like to be another animal, Birkhead affirms that, while we can never share fully another creature’s experience, ingenious experiments now permit us to know a great deal about what birds can see, hear, smell, taste, and feel.

Sight and hearing are relatively simple matters. It has long been common knowledge that these senses are far more acute in birds than in humans. Only recently, however, has the full sophistication of avian sight and hearing been understood, along with their implications for the evolution of bird behavior. In the 1970s it was discovered that birds are capable of seeing the ultraviolet range of the spectrum, invisible to humans. Birds that look drab to us may be spectacular in ultraviolet light. Courting females choose males that are most brilliant in appearance (presumably an indicator of health and vigor), a process that has driven the evolution of bizarre colors, plumes, and shapes among the males.

Birkhead often illustrates these discussions with vivid particular cases. From a blind at a cliffside guillemot colony, he observes a female brooding her egg suddenly grow alert long before Birkhead can see her mate flying in over the sea. When it comes to hearing, Birkhead explains how the enormous and asymetrically placed ears of the great grey owl can triangulate the location of a mouse running hidden under deep snow.

Smell is a much more complicated matter. Audubon notoriously got the matter wrong in his experiments with vultures (he apparently confused the turkey vulture, which has an acute sense of smell, with the black vulture, which does not). The bizarre kiwi of New Zealand, almost blind, depends largely on smell and feel. The olfactory sense, like the others, varies widely from species to species.

Taste and feel are more counterintuitive. A bird’s hard and horny beak appears inert. In fact it contains elaborate sensors of feel and taste. A duck’s beak sifts food from water and mud that the bird cannot see since its eyes face to the side. Many species of birds spend time preening one another in ways that clearly produce pleasure. Such lines of inquiry into sight, hearing, and taste have recently helped shift the study of bird behavior decisively away from the mechanistic explanations of the previous generation.

Bird navigation is one of the hottest current research topics. It was already known from bird banding, confirmed now by attaching tiny electronic tracking devices, that birds are capable of returning directly to a nest site across thousands of miles, or of reaching the identical wintering spot year after year. How they do this has been one of the most intractable mysteries in ornithology. Birds (and some other animals including bacteria) are now known to possess a magnetic sense, whose precise functioning is under active study.

Advertisement

Birkhead’s final chapter discusses the emotional life of birds, a line of inquiry long (and often still) disdained by professional ornithologists as appropriate for only the most sentimental of amateurs. Literary naturalists of a century ago, such as W.H. Hudson, John Burroughs, and Neltje Blanchan, whose best-selling Bird Neighbors I recall from my grandparents’ library, resorted to crude anthropomorphisms. Partly in reaction, professionals long dismissed the very idea that birds might have emotions. Brain scans now permit the detection and even measurement of emotional excitement in birds, while DNA shows that while many birds pair with one mate for at least a season, sexual cheating is rife. One of Birkhead’s students has even investigated sexual arousal in one species of African finch, the buffalo weaver.

Julie Zickefoose, an admired bird illustrator and rehabilitator of injured or foundling birds, addresses individual birds’ emotional lives from personal experience rather than from laboratory experiment. She has formed strong emotional bonds with individual birds, and she is convinced the birds reciprocate in some way that remains just beyond her efforts to know. When a bird she has cured or raised suddenly peels away from a wild flock and lands on her shoulder, is it displaying affection or associating her with food?

It is clear that birds can and do recognize human individuals, a point affirmed by Birkhead as well. To go further and attribute motives to them, however, risks falling into naive anthropomorphism. Zickefoose escapes much of the time, if not absolutely always, from this peril. Do not be put off by the pretty bluebird on her cover. Zickefoose’s recollections of encounters with individual birds have a redeeming measure of self-deprecating wit and skeptical common sense.

Notably Zickefoose refuses to make her bird patients into pets. Her goal is to restore them to the wild. Turning them into playthings distorts their natural behavior. She learned this lesson by sharing a good part of her adult life with a chestnut-fronted macaw that she bought when young, and that lived with her for twenty-three years. Deprived of a parrot’s normal rich social life, “Charlie” chooses her as his mate, and tries to copulate with her shoe (autopsy later showed that Charlie was female). A “crotchety tyrant,” Charlie expresses his (or her) jealousy of Zickefoose’s husband and children with ferocious bites. Zickefoose understands when Charlie begins to tear out his own feathers (a common problem with caged parrots) that he has become a deformed and incomplete animal, and she never replaces him with another pet parrot after he dies.

Zickefoose has a redeeming sense of the otherness of nature, acknowledging that its ways may be harsh and violent. The infant birds she raises are not “little people.” Some of them do not respond with anything but a frantic desire to escape. Some of them have to be euthanized. Nature must be respected on its own terms, and “it’s a tough world out there.”

The strength of these attractive essays is Zickefoose’s power of observation. Drawing and watching go together in her work, and her expressive watercolors show that she has been in eye contact with her subjects. Confronted with impossible tasks such as raising a nestful of infant chimney swifts or hummingbirds, she watches closely, improvises, and learns as she goes. The little nestlings have to be fed every twenty minutes, but she intrepidly takes them with her in a jacket with special pockets on errands to the grocery store, and keeps them alive.

Exactly like the journeymen bird-raisers of Tim Birkhead’s The Wisdom of Birds, she discovers by her labors many hitherto unknown things about the dietary needs of nestlings and the stages of their growth. She discovers that the professional literature can err about these matters. She learns that a nestling has a period of anorexia before leaving the nest. She learns that individual nestlings differ in personality. There is “so much to learn by handling a bird.”

So is she an amateur or a professional? She is self-taught, but wise and experienced. She is thrilled to be invited to a conference with professionals. But she clearly knows more than most of them about her specialty, and her contributions to ornithology are acknowledged.

The distinction between amateurs and professionals is not so old, after all. It came late to American ornithology in the 1880s, with the creation of paid positions as curators of birds at leading institutions such as the American Museum of Natural History in New York and Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology.

Robert Ridgway was a prominent member of that first generation of professional ornithologists. He grew up in rural Illinois infatuated with nature and eager to identify all the birds he found around him. After lucking into a job at the age of sixteen as a biologist helping to survey the transcontinental railway route in 1867, Ridgway was put in charge of the Smithsonian Institution’s bird collection in 1871. He went on to an arduous life’s work describing painstakingly every species and subspecies of bird north of the Isthmus of Panama in a formidably technical work that eventually reached eleven volumes, the last three completed posthumously.2

Advertisement

Ridgway and his professional colleagues had a touchy relationship with amateurs. The professionals wanted the financial support of amateurs as dues-paying members of their new association, the American Ornithologists’ Union (AOU), founded in 1883, and subscribers to its scientific journal, The Auk. But they also wanted to control the agenda and the vocabulary of their science, giving priority to taxonomy (the classification in evolutionary order of species and subspecies by close examination of long series of museum specimens) and avoiding what they regarded as the flaws of amateur “bird-watching”: sentimental narratives of descriptive natural history that tended to marvel at the deity’s creations. So the new professionals relegated amateurs to a lower class of membership in the AOU, excluded them—especially women—from leadership positions, and made competence at technical taxonomy the key to prestige in ornithology. In their turn, some amateurs derided Ridgway and his professional colleagues as “closet naturalists” who no longer spent time in the field.

Professionals commonly demarcate themselves from amateurs by a specialized vocabulary, and the ornithologists were no exception. Ridgway’s authoritative Catalogue established official Latin and English names for all bird species and subspecies in North America. Ridgway himself usually referred to birds by their Latin names, a practice that tended to exclude all but the most serious of amateurs. The amateurs saw with dismay the disappearance of a host of well-loved regional popular names for birds. “Bullbats” became nighthawks, “chewinks” became towhees in the new standardized official vocabulary, and amateurs felt this as a kind of professional tyranny. Nevertheless Ridgway accepted specimens and data from amateurs, and the two sides generally got along.

In one sense John James Audubon might be regarded as the first American professional ornithologist: he earned a living, however precariously, from his study and painting of birds. The other ornithologists of his era, by contrast, inherited money or did more conventional work for a living. Professional ornithologist was not a title that Audubon sought, however. Audubon wanted to be known as a “gentleman naturalist,” like his peers. That aspiration was manifested most clearly during the year 1826, when Audubon packed up more than 250 of his best watercolors and sailed to England to find sponsors and subscribers for his proposed volume of hand-colored engravings of American birds. Thanks to a new edition of the personal diary he kept during the voyage, for the first time we are able to enter to some degree into Audubon’s thoughts and feelings during that stressful year.

It may seem strange that we have only now an authoritative edition of that diary in something close to its original form. Audubon’s granddaughter, Maria Rebecca Audubon, first published an edition of the diaries in 1897. She bowdlerized them beyond recognition, however, and destroyed the originals in her possession. A copy of the diary for the year 1826 survives only by the fortunate accident of having been sold to a bibliophile. The biographer Alice Ford published a more faithful edition of it in 1967, though she still thought it necessary to put the diary into smooth English, and even added a few phrases that she thought would clarify the author’s intention. But Audubon’s 1826 diary was anything but smooth. His language was a mixture of English, French, and personal invention. And his impulsive and emotional character shaped the leaps and darts of his prose, exacerbated by the stresses, excitements, and, finally, triumphs of that tumultuous year.

The diary has a conversational and even playful tone, since it takes the form of a dialogue with Audubon’s much-missed wife, Lucy. The relationship with Lucy provides a major subtext. The vagaries of transportation prevented him from receiving any letters at all from her for many months. He came to suspect that she had broken off with him. He kept up his side of the correspondence, nonetheless, filling his letters maladroitly with effusive details about his close (but almost certainly platonic) friendships with aristocratic women in England and Scotland. Writes the editor, “Audubon liked women.”

The diary shows Audubon keenly, even painfully, aware of his status. On the one hand, he presented himself proudly as “the woodsman,” keeping his hair long and cultivating a simple manner, and, when asked, imitating the calls of wild turkeys and barred owls in elegant salons. He understood that the woodsman persona was what his new English and Scottish friends expected and wanted. On the other hand, determined to be accepted as an equal, he went out to his meetings with the rich and powerful of Liverpool, Manchester, and Edinburgh with a sword cane, a hat, and gloves. He signed his letters “J.J. Audubon, Naturalist.” He bridled at his friends’ suggestion that he charge admission for the exhibitions of his watercolors that he mounted in each city, even though he needed the money. He did not want to be considered an artisan.

At first Audubon suffered from self-conscious anxiety before meeting wealthy potential patrons. Soon, however, he established the worth of himself and his work. “He [Lord Stanley], Lucy, kneeled down on the rich carpet to examine my style closely.” His success tells us as much about the taste for nature and curiosity about America that moved parts of the British elite in the 1820s as it does about Audubon’s charm and showmanship and the brilliance of his sample watercolors.

Audubon signed the last page of his diary “John J. Audubon, Citizen of the United States of North America.” He found much in England that made him proud of his American identity. The smoke of Liverpool and Manchester made him homesick for American forests. England, by contrast, had only “Saplins.” And those, he expected, were “marked and numbered and, for all that I know, pays either a Tax to the Government or a tythe to the Parish.” He chafed at the “no trespassing” signs he encountered when he wanted to be “running across the Fields.”

As an ardent hunter, Audubon disdained the half-tame birds of a private English hunting preserve and “the Frisks [aristocr atic youths who] murder them by Thousands.” He preferred American hunting. There game birds and animals are accessible to everyone, as

Free and as Wild as Nature made them to Excite the active healthfull pursuer to search after it and pay for it thro the pleasure of Hunting it downe against all difficulties.

American freedom, for Audubon, was rooted in the unstructured life that he enjoyed during his sojourns in the wilderness.

These things were “a Trifle,” however, compared to the poverty that shocked him. “Beggars in England are like our Ticks of Louisiana…. England is now Rich with poverty.” In Manchester he noted that the horses were fat and the working people were thin and sallow because of “confinement” in the factories.

Audubon was certainly not a rustic. He had, after all, been raised in a planter’s household near Nantes, on the French Breton coast. The diaries reveal more autodidactic cultivation in Audubon than one might expect. He was well aware of the Western artistic tradition (he had studied with Thomas Sully in Philadelphia), and seems to have read the main authors of the day, from Walter Scott to Byron. He shared with Lucy a predilection for Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy. He went gladly to concerts and evaluated them for Lucy. The quality that he wanted to display in Europe was simplicity (echoing on this point Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin), but he bridled at any intimation that his simplicity made him somehow backward. He was most pleased when a new acquaintance called him “simple Intelligent.”

Observation was central to Audubon’s enterprise. He thought of his occupation as “Drawing and Studying the Habits of the Birds that I saw about me.” The two projects went together: his pictures were based on close observation (often ginned up a little, occasionally inaccurate), and they were supposed to be accompanied by essays on the life history of each species that he painted. He already began writing these while he was in Edinburgh, and he lectured from them before scientific societies and published some of them in Scottish periodicals. He had only contempt for those who did not study living animals and plants in the field, whom he, too, called “closet” naturalists. When his first engraver in Edinburgh, William Home Lizars, commented, on being shown Audubon’s portfolio, “My God, I never saw anything like this before,” he was referring to the dramatic events portrayed in the best of Audubon’s work. Even the ablest illustrators up to then, such as Thomas Bewick, had portrayed birds in stiff, inactive poses.

Lizars was thunderstruck by two pictures that remain favorites today: two frantic mockingbirds defending their nest from a rattlesnake, and a red-shouldered hawk plunging, claws first, into a wild-eyed covey of quail. In his transparent delight in portraying dramatic moments of bird behavior, Audubon not only brought a Romantic sensibility to bird painting, as is often noted, but also prefigured modern ornithology’s turn toward the study of bird behavior.

Everyone knows that Audubon shot all the birds that he painted. One hostess at a great estate near Liverpool had to ask him to spare her pet robin in the garden. He seemed unaware of any conflict between the pride he felt in his prowess as a hunter and his evident love for nature. He understood the threat of “the cruel destroyer Man.” He knew enough of early industrialization in the United States to foresee the end of nature there. He imagined summoning Sir Walter Scott, whom he hoped (and feared) to meet, to describe American nature so powerfully that he could “Wrestle with Mankind and stop their Increasing ravages on Nature….” Otherwise

the Hills will be levelled with the swamp and probably this very swamp have become a mound covered with a Fortress of a thousand Guns…. Fishes will no longer bask on this surface, the Eagle scarce ever alight, and those millions of songsters will be drove away by Man.

Every student of birds who has come after must reckon with Audubon. Robert Ridgway named his only child for him, but “Audie” Ridgway died young. Tim Birkhead finds Audubon too impulsive, too often mistaken. Julie Zickefoose, like the master, joins drawing and observation, more carefully but with no less passion, carrying forward his restless curiosity: “I know that I will never be through learning about how birds’ minds work.”

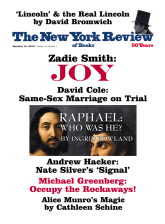

This Issue

January 10, 2013

Joy

Occupy the Rockaways!

How He Got It Right

-

1

Tim Birkhead, The Wisdom of Birds: An Illustrated History of Ornithology (Bloomsbury, 2008). ↩

-

2

The Birds of North and Middle America. A Descriptive Catalogue of the Higher Groups, Genera, Species and Subspecies of Birds Known to Occur in North America, from the Arctic Islands to the Isthmus of Panama, the West Indies and other Islands of the Caribbean Sea, and the Gallapagos Archipelago (US National Museum Bulletin No. 50, 1901–1950). Ridgway also published 553 technical papers and twenty-three monographs. ↩