1.

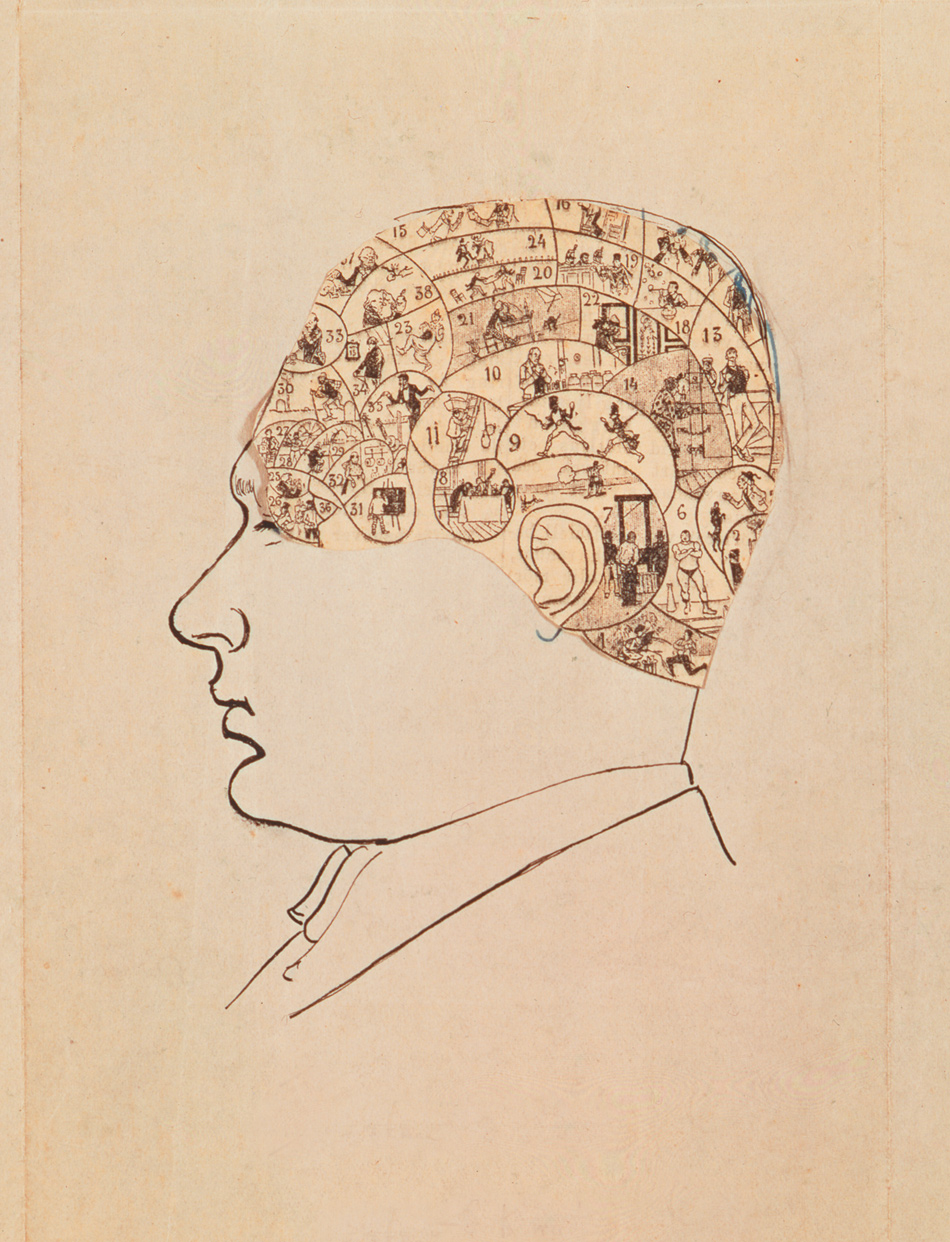

The problem of consciousness remains with us. What exactly is it and why is it still with us? The single most important question is: How exactly do neurobiological processes in the brain cause human and animal consciousness? Related problems are: How exactly is consciousness realized in the brain? That is, where is it and how does it exist in the brain? Also, how does it function causally in our behavior?

To answer these questions we have to ask: What is it? Without attempting an elaborate definition, we can say the central feature of consciousness is that for any conscious state there is something that it feels like to be in that state, some qualitative character to the state. For example, the qualitative character of drinking beer is different from that of listening to music or thinking about your income tax. This qualitative character is subjective in that it only exists as experienced by a human or animal subject. It has a subjective or first-person existence (or “ontology”), unlike mountains, molecules, and tectonic plates that have an objective or third-person existence. Furthermore, qualitative subjectivity always comes to us as part of a unified conscious field. At any moment you do not just experience the sound of the music and the taste of the beer, but you have both as part of a single, unified conscious field, a subjective awareness of the total conscious experience. So the feature we are trying to explain is qualitative, unified subjectivity.

Now it might seem that is a fairly well-defined scientific task: just figure out how the brain does it. In the end I think that is the right attitude to have. But our peculiar history makes it difficult to have exactly that attitude—to take consciousness as a biological phenomenon like digestion or photosynthesis, and figure out how exactly it works as a biological phenomenon. Two philosophical obstacles cast a shadow over the whole subject. The first is the tradition of God, the soul, and immortality. Consciousness is not a part of the ordinary biological world of digestion and photosynthesis: it is part of a spiritual world. It is sometimes thought to be a property of the soul and the soul is definitely not a part of the physical world. The other tradition, almost as misleading, is a certain conception of Science with a capital “S.” Science is said to be “reductionist” and “materialist,” and so construed there is no room for consciousness in Science. If it really exists, consciousness must really be something else. It must be reducible to something else, such as neuron firings, computer programs running in the brain, or dispositions to behavior.

There are also a number of purely technical difficulties to neurobiological research. The brain is an extremely complicated mechanism with about a hundred billion neurons in humans, and most investigative techniques are, as the researchers cheerfully say, “invasive.” That means you have to kill or hideously maim the animal in order to investigate the operation of the brain. Noninvasive research techniques, such as brain imaging, are useful, but they have so far not given us the sort of detailed understanding of the workings of the conscious mind that we would like.

2.

Christof Koch has written about these issues before, including an important book I reviewed in these pages, The Quest for Consciousness.1 His current book abandons the biological approach he adapted earlier, and which I have articulated above. According to his current view, consciousness has no special connection with biology. He follows the Italian neuroscientist Giulio Tononi,2 now at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, in thinking that the key to consciousness is information theory, which, he writes, “exhaustively catalogues and characterizes the interactions among all parts of any composite identity.” It does so by quantifying the information about such interactions as “bits” that can be measured, stored, and transmitted. The application of information theory made by Tononi and Koch emphasizes that consciousness requires that the information that constitutes consciousness should be both “differentiated” and “integrated.” In one of Tononi’s examples, in experiencing a red square we “differentiate” the property of redness and the property of squareness, but the experience is “integrated” in that it “cannot be decomposed into the separate experience of red and the separate experience of a square.” Tononi goes on,

Similarly, experiencing the full visual field cannot be decomposed into experiencing separately the left half and the right half: such a possibility does not even make sense to us, since experience is always whole.

According to Koch, any system at all that has processes describable by information theory is, at least to some degree, conscious. But since any system that has causal relations can be described in the vocabulary of information theory, it turns out that consciousness is everywhere. Panpsychism follows. As he tells us:

Advertisement

By postulating that consciousness is a fundamental feature of the universe, rather than emerging out of simpler elements, integrated information theory is an elaborate version of panpsychism.… Once you assume that consciousness is real and ontologically distinct [i.e., exists apart] from its physical substrate, then it is a simple step to conclude that the entire cosmos is suffused with sentience. We are surrounded and immersed in consciousness….

No matter whether the organism or artifact hails from the ancient kingdom of Animalia or from its recent silicon offspring, no matter whether the thing has legs to walk, wings to fly, or wheels to roll with—if it has both differentiated and integrated states of information, it feels like something to be such a system; it has an interior perspective.

In other words it is conscious. So:

personal computers, embedded processors, and smart phones…might be minimally conscious.

Koch and Tononi begin by investigating biological consciousness in humans and animals. They develop a theory that consciousness is information. But such information is not confined to biological systems. You also find consciousness in, say, smartphones. So, in the end, for these authors, there is nothing especially biological about consciousness.

The integrated information theory of consciousness makes a number of important predictions. Among them is that, in the specific case of biological consciousness, information arises from causal interactions within the nervous system, and when those interactions cannot take place anymore the amount of consciousness shrinks. For example, there is less consciousness in deep sleep than in wakefulness. According to Tononi this is because there is less integration going on in the brain in deep sleep compared with that in wakefulness. Tononi and his colleague Marcello Massimini, now a professor in Milan, set out to prove this by attaching electrodes to volunteers both sleeping and awake. A difference of results, according to Tononi, showed that in deep-sleeping subjects the integration breaks down.

Koch discusses a number of other issues in the book: notably free will, the relation of science and religion, and the role of unconscious mental processes. I will discuss some of these later, but the single most important claim is the analysis of consciousness based in information theory.

3.

Two objections stand out immediately. The first is that no reason has been given at all why there should be any special connection between information theory and consciousness. In his earlier views, Koch argued that consciousness is explained by synchronized neuron firings. Now he objects to that previous view. The objection is: Why should there be any connection between certain rates of neuron firings and consciousness? The same question arises with information theory: Why should information theory give us the essence of subjectivity? What is the connection supposed to be? My second objection is that the theory implies panpsychism, and pansychism is absurd for a reason I can explain briefly.

Consciousness comes in units. The qualitative state of drinking beer is different from finding the money in your wallet to pay for it. But a consequence of its subjectivity is its unity. So for example, I am conscious and you are conscious but each consciousness is separate from the other; they do not smear into each other like adjoining puddles of mud. Consciousness cannot be spread over the universe like a thin veneer of jam; there has to be a point where my consciousness ends and yours begins. For people who accept panpsychism, who attribute consciousness, as Koch does, to the iPhone, the question is: Why the iPhone? Why not each part of it? Each microprocessor? Why not each molecule? Why not the whole communication system of which the iPhone is a part? The problem with panpsychism is not that it is false; it does not get up to the level of being false. It is strictly speaking meaningless because no clear notion has been given to the claim. Consciousness comes in units and panpsychism cannot specify the units.

4.

Christof Koch describes his book as the “Confessions of a Romantic Reductionist.” But this is misleading. His book is explicitly and aggressively antireductionist, it contains no confessions, and if you are looking for a romantic book—this is not it. A crucial sentence is this:

Experience, the interior perspective of a functioning brain, is something fundamentally different from the material thing causing it and…it can never be fully reduced to physical properties of the brain.

And:

I believe that consciousness is a fundamental, an elementary, property of living matter. It can’t be derived from anything else; it is a simple substance, in Leibnitz’s words.

This is antireductionism with a vengeance. Indeed, as he himself says, it is a form of dualism. You are reductionist if you think that consciousness is really something else, and that the first-person ontology—the sense I have that I exist—can be shown to be third-person ontology—my sense is reducible to something else. Favorite candidates for reducing consciousness to something else are neuron firings, computer processes, and behavior. Antireductionism does not become reductionism by being described as “romantic.” There is no sense whatever—romantic or otherwise—in which Koch is a reductionist about consciousness.

Advertisement

Also, I could not find any confessions in the book. “Confessions” implies that he admits he has done something wrong. There are many personal reflections in the book about himself, his family, his children, his dogs, his mountain-climbing experiences, and his work as a scientist. His friends, of whom I am one, will find many of these quite moving. But any confession where he actually admits to some serious or even trivial misdeed is conspicuously absent from the book. An accurate subtitle would be “Personal Reflections of a Scientific Dualist.”

5.

On the question of free will, Koch endorses the most extreme of interpretations of the experiments conducted by the late neuroscientist Benjamin Libet, whose experiments drew on the work of other scientists. Libet would tell his subjects to perform some intentional but trivial act, such as pushing a button or flicking their wrist, and to do it every so often whenever they feel like it. But he asked them to observe on a clock exactly the point at which they made up their mind to do it and he found that at exactly the point at which the intention in action began, there was an interval between increased brain activity in a specific area of the brain and the awareness by the subject that he is beginning to push the button or perform a similar action. In short, before I was aware that I was about to push the button, my brain was getting ready to do so. The brain has an extra activity, called the “readiness potential,” prior to the reported awareness of the onset of the action. This can last a couple hundred milliseconds or sometimes even longer.

Now what is one to make of these data? I think the most extreme unwarranted interpretation is that they show that we do not have free will. The brain decides to do something before the mind knows what it is doing. The brain decides to act and the mind becomes aware of this later on. Koch endorses this extreme naive view.

I think the data do not show anything of this sort. The cases in question are all cases where the subject has already made up his mind to eventually perform a course of action, and the brain has an increased activity prior to his awareness of a conscious decision to physically perform it; but the presence of the readiness potential does not constitute a causally sufficient condition for the performance of the action. It could be the case that a person would have been inclined to push a button, that the brain then undertook the activity called readiness potential, and that the person would not push the button. Readiness potential in the brain is not a condition that is sufficient to cause the act. It is associated with the act but does not determine it. We need much more research before we can give a confident interpretation of the readiness potential data. By the way, the pedant in me is annoyed by the fact that he attributes all of this to the work of Ben Libet when in fact the same “Bereitschaftspotential” was discovered in the 1970s by two German scientists, Lüder Deecke and H.H. Kornhuber, and their colleagues.3 Koch makes no mention of Deecke and Kornhuber.

6.

Koch’s proposal to explain consciousness by the processing of information marks a major shift in the type of explanation he is seeking. Standard explanations in biology are causal; for example, we want to know how genes cause physical and other traits and how brain processes cause consciousness. But Koch’s explanation abandons this project. He is not saying that information causes consciousness; he is saying that certain information just is consciousness, and because information is everywhere consciousness is everywhere. I think that if you analyze this carefully, you will see that the view is incoherent.

To put the explanation bluntly: consciousness is independent of an observer. I am conscious no matter what anybody thinks. But information is typically relative to observers. These sentences, for example, contain information that make sense only relative to our capacity to interpret them. So you can’t explain consciousness by saying it consists of information, because information only exists relative to consciousness.

Information is one of the most confused notions in contemporary intellectual life. First of all, there is a distinction between information in the ordinary sense in which it always has a content—that is, typically, that such and such is the case or that such and such an action is to be performed. That kind of information is different from information in the sense of the mathematical “theory of information,” originally invented by Claude Shannon of Bell Labs. The mathematical theory of information is not about content, but how content is encoded and transmitted. Information according to the mathematical theory of information is a matter of bits of data where data are construed as symbols. In more traditional terms, the commonsense conception of information is semantical, but the mathematical theory of information is syntactical. The syntax encodes the semantics. This is in a broad sense of “syntax” which would include, for example, electrical charges.

Information theory has proved immensely powerful in a number of fields and may become more powerful as new ways are found to encode and transmit content, construed as symbols. Tononi and Koch want to use both types of information, they want consciousness to have content, but they want it to be measurable using the mathematics of information theory.

To explore these ideas two distinctions must be made clear. The first is between two senses of the objective and subjective distinction. This famous distinction is ambiguous between an epistemic sense (where “epistemic” means having to do with knowledge) and an ontological sense (where “ontological” means having to do with existence). In the epistemic sense, there is a difference between those claims that can be settled as a matter of truth or falsity objectively, where truth and falsity do not depend on the attitudes of makers and users of the claim. If I say that Rembrandt was born in 1606, that claim is epistemically objective. If I say that Rembrandt was the best Dutch painter ever, that is, as they say, a matter of “subjective opinion”; it is epistemically subjective.

But also there is an ontological sense of the subjective/objective distinction. In that sense, subjective entities only exist when they are experienced by a human or animal subject. Ontologically objective entities exist independently of any experience. So pains, tickles, itches, suspicions, and impressions are ontologically subjective; while mountains, molecules, and tectonic plates are ontologically objective. Part of the importance of this distinction, for this discussion, is that mental phenomena can be ontologically subjective but still admit of a science that is epistemically objective. You can have an epistemically objective science of consciousness even though it is an ontologically subjective phenomenon. Ben Libet was practicing such an epistemically objective science; so are a wide variety of scientists ranging, for example, from Antonio Damasio to Oliver Sacks.

This distinction underlies another distinction—between those features of the world that exist independently of any human attitudes and those whose existence requires such attitudes. I describe this as the difference between those features that are observer-independent and those that are observer-relative. So, ontologically objective features like mountains and tectonic plates have an existence that is observer-independent; but marriage, property, money, and articles in The New York Review of Books have an observer-relative existence. Something is an item of money or a text in an intellectual journal only relative to the attitudes people take toward it. Money and articles are not intrinsic to the physics of the phenomena in question.

Why are these distinctions important? In the case of consciousness we have a domain that is ontologically subjective, but whose existence is observer-independent. So we need to find an observer-independent explanation of an observer-independent phenomenon. Why? Because all observer-relative phenomena are created by consciousness. It is only money because we think it is money. But the attitudes we use to create the observer-relative phenomena are not themselves observer-relative. Our explanation of consciousness cannot appeal to anything that is observer-relative—otherwise the explanation would be circular. Observer-relative phenomena are created by consciousness, and so cannot be used to explain consciousness.

The question then arises: What about information itself? Is its existence observer-independent or observer- relative? There are different sorts of information, or if you like, different senses of “information.” In one sense, I have information that George Washington was the first president of the United States. The existence of that information is observer-independent; I have that information regardless of what anybody thinks. It is a mental state of mine, which while it is normally unconscious can readily become conscious. Any standard textbook on American history will contain the same information. What the textbook contains, however, is observer-relative. It is only relative to interpreters that the marks on the page encode that information. With the exception of our mental thoughts—conscious or potentially conscious—all information is observer-relative. And in fact, except for giving examples of actual conscious states, all of the examples that Tononi and Koch give of information systems—computers, smart phones, digital cameras, and the Web, for example—are observer-relative.

We cannot explain consciousness by referring to observer-relative information because observer-relative information presupposes consciousness already. What about the mathematical theory of information? Will that come to the rescue? Once again, it seems to me that all such cases of “information” are observer-relative. The reason for the ubiquitousness of information in the world is not that information is a pervasive force like gravity, but that information is in the eye of the beholder, and beholders can attach information to anything they want, provided that it meets certain causal conditions. Remember, observer relativity does not imply arbitrariness, it does not imply epistemic subjectivity.

An example prominently discussed by Tononi will make this clear. He considers the case of a photodiode that turns on when the light is on and off when the light is off. So the photodiode contains two states and has minimal bits of information. Is the photodiode conscious? Tononi tells us, and Koch is committed to the same view, that yes, the photodiode is conscious. It has a minimal amount of consciousness, one bit to be exact. But now, what fact about it makes it conscious? Where does its subjectivity come from? Well, it contains the information that the light is either on or off. But the objection to that is: the information only exists relative to a conscious observer. The photodiode knows nothing about light being on or off, it just responds differentially to photon emissions. It is exactly like a mercury thermometer that expands or contracts in a way that we can use to measure the temperature in the room. The mercury in the glass knows nothing about temperature or anything else; it just expands or contracts in a way that we can use to gain information.

Same with the photodiode. The idea that the photodiode is conscious, even a tiny bit conscious, just in virtue of matching a luminance in the environment, does not seem to be worth serious consideration. I have the greatest admiration for Tononi and Koch but the idea that a photodiode becomes conscious because we can use it to get information does not seem up to their usual standards.

A favorite example in the literature is the rings in a tree stump. They contain information about the age of the tree. But what fact about them makes them information? The answer is that there is a correlation between the annual rings on the tree stump and the cycle of the seasons, and the different phases of the tree’s growth, and therefore we can use the rings to get information about the tree. The correlation is just a brute fact; it becomes information only when a conscious interpreter decides to treat the tree rings as information about the history of the tree. In short, you cannot explain consciousness by referring to observer-relative information, because the information in question requires consciousness. Information is only information relative to some consciousness that assigns the informational status.

Well, why could not the brute facts that enable us to assign informational interpretations themselves be conscious? Why are they not sufficient for consciousness? The mercury expands and contracts. The photodiode goes on or off. The tree gets another ring with each passing year. Is that supposed to be enough for consciousness? As long as we have the notion of “information” in our explanation, it might look as if we are explaining something, because, after all, there does seem to be a connection between consciousness and observer-independent information.

There is no doubt some information in every conscious state in the ordinary content sense of information. Even if I just have a pain, I have information, for example that it hurts and that I am injured. But once you recognize that all the cases given by Koch and Tononi are forms of information relative to an observer, then it seems to me that their approach is incoherent. The matching relations themselves are not information until a conscious agent treats them as such. But that treatment cannot itself explain consciousness because it requires consciousness. It is just an example of consciousness at work.

7.

There are many other interesting parts of Koch’s book that I have not had the space to discuss, and as always Koch’s discussions are engaging and informative. I would not wish my misgivings to detract from the real merits of his book. But the primary intellectual ambitions of the book—namely to offer a model for explaining consciousness and to suggest a solution to the problem of free will and determinism—do not seem to me successful.

This Issue

January 10, 2013

Joy

Occupy the Rockaways!

How He Got It Right

-

1

Robert and Company, 2004; see my review in these pages, January 13, 2005. ↩

-

2

Giulio Tononi, “Consciousness as Integrated Information: A Provisional Manifesto,” The Biological Bulletin, Vol. 215, No. 3 (2008). ↩

-

3

Luder Deecke, Berta Grozinger, and H.H. Kornhuber, “Voluntary Finger Movement in Man: Cerebral Potentials and Theory,” Biological Cybernetics (1976). ↩