I have been struck by parallels between the challenges facing the Federal Reserve today and those when I first entered the Federal Reserve System as a neophyte economist in 1949.

Most striking then, as now, was the commitment of the Federal Reserve, which was and is a formally independent body, to maintaining a pattern of very low interest rates, ranging from near zero to 2.5 percent or less for Treasury bonds. If you feel a bit impatient about the prevailing rates, quite understandably so, recall that the earlier episode lasted fifteen years.

The initial steps taken in the midst of the depression of the 1930s to support the economy by keeping interest rates low were made at the Fed’s initiative. The pattern was held through World War II in explicit agreement with the Treasury. Then it persisted right in the face of double-digit inflation after the war, increasingly under Treasury and presidential pressure to keep rates low.

The growing restiveness of the Federal Reserve was reflected in testimony by Marriner Eccles in 1948:

Under the circumstances that now exist the Federal Reserve System is the greatest potential agent of inflation that man could possibly contrive.

This was pretty strong language by a sitting Fed governor and a long-serving board chairman. But it was then a fact that there were many doubts about whether the formality of the independent legal status of the central bank—guaranteed since it was created in 1913—could or should be sustained against Treasury and presidential importuning. At the time, the influential Hoover Commission on government reorganization itself expressed strong doubts about the Fed’s independence. In these years calls for freeing the market and letting the Fed’s interest rates rise met strong resistance from the government.

Treasury debt had enormously increased during World War II, exceeding 100 percent of the GDP, so there was concern about an intolerable impact on the budget if interest rates rose strongly. Moreover, if the Fed permitted higher interest rates this might lead to panicky and speculative reactions. Declines in bond prices, which would fall as interest rates rose, would drain bank capital. Main-line economists, and the Fed itself, worried that a sudden rise in interest rates could put the economy back in recession.

All of those concerns are in play today, some sixty years later, even if few now take the extreme view of the first report of the then new Council of Economic Advisers in 1948: “low interest rates at all times and under all conditions, even during inflation,” it said, would be desirable to promote investment and economic progress. Not exactly a robust defense of the Federal Reserve and independent monetary policy.

Eventually, the Federal Reserve did get restless, and finally in 1951 it rejected overt presidential pressure to maintain a ceiling on long-term Treasury rates. In the event, the ending of that ceiling, called the “peg,” was not dramatic. Interest rates did rise over time, but with markets habituated for years to a low interest rate, the price of long-term bonds remained at moderate levels. Monetary policy, free to act against incipient inflationary tendencies, contributed to fifteen years of stability in prices, accompanied by strong economic growth and high employment. The recessions were short and mild.

No doubt, the challenge today of orderly withdrawal from the Fed’s broader regime of “quantitative easing”—a regime aimed at stimulating the economy by large-scale buying of government and other securities on the market—is far more complicated. The still-growing size and composition of the Fed’s balance sheet imply the need for, at the least, an extended period of “disengagement,” i.e., less active purchasing of bonds so as to keep interest rates artificially low. Moreover, the extraordinary commitment of Federal Reserve resources, alongside other instruments of government intervention, is now dominating the largest sector of our capital markets, that for residential mortgages. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to note that the Federal Reserve, with assets of $3.5 trillion and growing, is, in effect, acting as the world’s largest financial intermediator. It is acquiring long-term obligations in the form of bonds and financing those purchases by short-term deposits. It is aided and abetted in doing so by its unique privilege to create its own liabilities.

The beneficial effects of the actual and potential monetizing of public and private debt, which is the essence of the quantitative easing program, appear limited and diminishing over time. The old “pushing on a string” analogy is relevant. The risks of encouraging speculative distortions and the inflationary potential of the current approach plainly deserve attention.

All of this has given rise to debate within the Federal Reserve itself. In that debate, I trust that sight is not lost of the merits—economic and political—of an ultimate return to a more orthodox central banking approach. Concerning possible changes in Fed policy, it is worth quoting from Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke’s remarks on June 19:

Advertisement

Going forward, the economic outcomes that the Committee sees as most likely involve continuing gains in labor markets, supported by moderate growth that picks up over the next several quarters as the near-term restraint from fiscal policy and other headwinds diminishes. We also see inflation moving back toward our 2 percent objective over time.

If the incoming data are broadly consistent with this forecast, the Committee currently anticipates that it would be appropriate to moderate the monthly pace of [asset] purchases later this year. And if the subsequent data remain broadly aligned with our current expectations for the economy, we would continue to reduce the pace of purchases in measured steps through the first half of next year, ending purchases around midyear.

In this scenario, when asset purchases ultimately come to an end, the unemployment rate would likely be in the vicinity of 7 percent, with solid economic growth supporting further job gains, a substantial improvement from the 8.1 percent unemployment rate that prevailed when the Committee announced this program.

I would like to emphasize once more the point that our policy is in no way predetermined and will depend on the incoming data and the evolution of the outlook as well as on the cumulative progress toward our objectives. If conditions improve faster than expected, the pace of asset purchases could be reduced somewhat more quickly. If the outlook becomes less favorable, on the other hand, or if financial conditions are judged to be inconsistent with further progress in the labor markets, reductions in the pace of purchases could be delayed.

Indeed, should it be needed, the Committee would be prepared to employ all of its tools, including an increase in the pace of purchases for a time, to promote a return to maximum employment in a context of price stability.

I do not doubt the ability and understanding of Chairman Bernanke and his colleagues. They have a considerable range of instruments available to them to manage the transition, including the novel approach of paying interest on banks’ excess reserves, potentially sterilizing their monetary impact. What is at issue—what is always at issue—is a matter of good judgment, leadership, and institutional backbone. A willingness to act with conviction in the face of predictable political opposition and substantive debate is, as always, a requisite part of a central bank’s DNA.

Those are not qualities that can be learned from textbooks. Abstract economic modeling and the endless regression analyses of econometricians will be of little help. The new approach of “behavioral” economics itself is recognition of the limitations of mathematical approaches, but that new “science” is in its infancy.

A reading of history may be more relevant. Here and elsewhere, the temptation has been strong to wait and see before acting to remove stimulus and then moving toward restraint. Too often, the result is to be too late, to fail to appreciate growing imbalances and inflationary pressures before they are well ingrained.

There is something else that is at stake beyond the necessary mechanics and timely action. The credibility of the Federal Reserve, its commitment to maintaining price stability, and its ability to stand up against partisan political pressures are critical. Independence can’t just be a slogan. Nor does the language of the Federal Reserve Act itself assure protection, as was demonstrated in the period after World War II. Then, the law and its protections seemed clear, but it was the Treasury that for a long time called the tune.

In the last analysis, independence rests on perceptions of high competence, of unquestioned integrity, of broad experience, of nonconflicted judgment and the will to act. Clear lines of accountability to Congress and the public will need to be honored.

Moreover, maintenance of independence in a democratic society ultimately depends on something beyond those institutional qualities. The Federal Reserve—any central bank—should not be asked to do too much, to undertake responsibilities that it cannot reasonably meet with the appropriately limited powers provided.

I know that it is fashionable to talk about a “dual mandate”—the claim that the Fed’s policy should be directed toward the two objectives of price stability and full employment. Fashionable or not, I find that mandate both operationally confusing and ultimately illusory. It is operationally confusing in breeding incessant debate in the Fed and the markets about which way policy should lean month-to-month or quarter-to-quarter with minute inspection of every passing statistic. It is illusory in the sense that it implies a trade-off between economic growth and price stability, a concept that I thought had long ago been refuted not just by Nobel Prize winners but by experience.

Advertisement

The Federal Reserve, after all, has only one basic instrument so far as economic management is concerned—managing the supply of money and liquidity. Asked to do too much—for example, to accommodate misguided fiscal policies, to deal with structural imbalances, or to square continuously the hypothetical circles of stability, growth, and full employment—it will inevitably fall short. If in the process of trying it loses sight of its basic responsibility for price stability, a matter that is within its range of influence, then those other goals will be beyond reach.

Back in the 1950s, after the Federal Reserve finally regained its operational independence, it also decided to confine its open market operations almost entirely to the short-term money markets—the so-called “Bills Only Doctrine.” A period of remarkable economic success ensued, with fiscal and monetary policies reasonably in sync, contributing to a combination of relatively low interest rates, strong growth, and price stability. That success faded as the Vietnam War intensified, and as monetary and fiscal restraints were imposed too late and too little. The absence of enough monetary discipline in the face of the overt inflationary pressures of the war left us with a distasteful combination of both price and economic instability right through the 1970s—a combination not inconsequentially complicated further by recurrent weakness in the dollar.

We cannot “go home again,” not to the simpler days of the 1950s and 1960s. Markets and institutions are much larger, far more complex. They have also proved to be more fragile, potentially subject to large destabilizing swings in behavior. There is the rise of “shadow banking”—the nonbank intermediaries such as investment banks, hedge funds, and other institutions overlapping commercial banking activities. Partly as a result, there is the relative decline of regulated commercial banks, and the rapid innovation of new instruments such as derivatives. All these have challenged both central banks and other regulatory authorities around the developed world. But the simple logic remains; and it is, in fact, reinforced by these developments. The basic responsibility of a central bank is to maintain reasonable price stability—and by extension to concern itself with the stability of financial markets generally.

In my judgment, those functions are complementary and should be doable.

I happen to believe it is neither necessary nor desirable to try to pin down the objective of price stability by setting out a single highly specific target or target zone for a particular measure of prices. After all, some fluctuations in prices, even as reflected in broad indices, are part of a well-functioning market economy. The point is that no single index can fully capture reality, and the natural process of recurrent growth and slowdowns in the economy will usually be reflected in price movements.

With or without a numerical target, broad responsibility for price stability over time does not imply an inability to conduct ordinary countercyclical policies. Indeed, in my judgment, confidence in the ability and commitment of the Federal Reserve (or any central bank) to maintain price stability over time is precisely what makes it possible to act aggressively in supplying liquidity in recessions or when the economy is in a prolonged period of growth but well below its potential.

Credibility is an enormous asset. Once earned, it must not be frittered away by yielding to the notion that a “little inflation right now” is a good thing to release animal spirits among entrepreneurs and to pep up investment. The implicit assumption behind that siren call must be that the inflation rate can be manipulated to reach economic objectives—up today, maybe a little more tomorrow, and then pulled back on command. But all experience amply demonstrates that inflation, when deliberately started, is hard to control and reverse. Credibility is lost.

I have long argued that concern for “stability” by central banks must range beyond prices for goods and services to the stability and strength of financial markets and institutions generally. I am afraid we collectively lost sight of the importance of banks and markets that would robustly be able to maintain efficient and orderly functioning in time of stress. Nor has market discipline alone restrained episodes of unsustainable exuberance before the point of crisis. Too often, we were victims of theorizing that markets and institutions could and would take care of themselves.

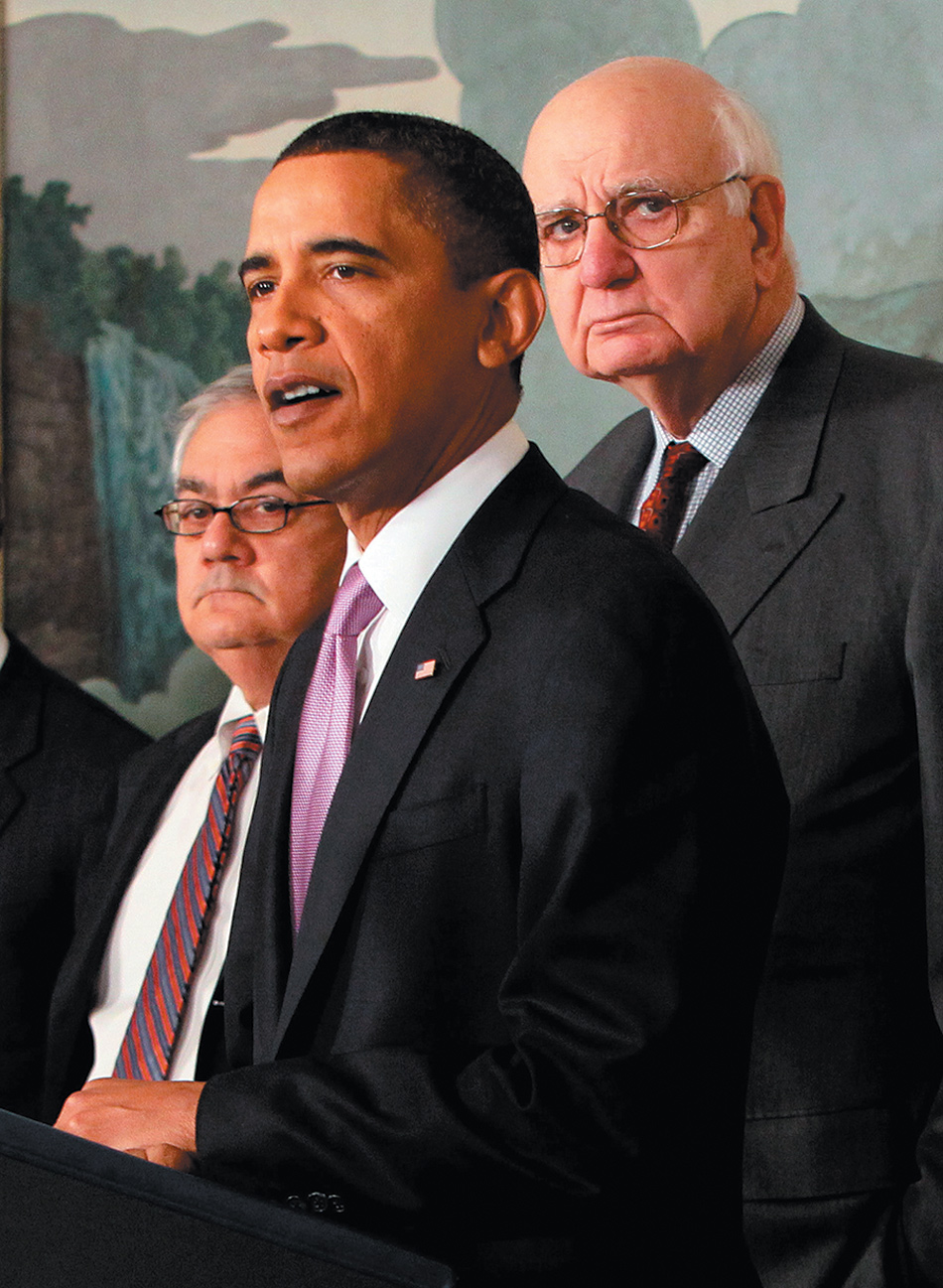

I expressed my concerns in that respect when I was chairman of the Fed; and their relevance to central banking and the organization of regulatory authority were more fully expressed several years ago. Congress was then beginning to consider reform legislation. It was recognized that regulatory agencies, perhaps most specifically the Federal Reserve, had exhibited a certain laxity and ineffectiveness in the period leading up to the financial breakdown of 2008, particularly with respect to the mortgage market.

Nevertheless, the provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 implicitly recognized and even reinforced the range of Federal Reserve regulatory and supervisory authority. To that end, it provided for a new vice-chairman of the board specifically charged with responsibilities for bank supervision. (Apparently one governor has in practice undertaken that substantial role, but for some reason after almost three years the specific position of vice-chairman remains unfilled. That lapse unfortunately leaves open the question of whether the administration and the Federal Reserve really appreciate the long-term significance of maintaining the Fed’s supervisory responsibilities.)

The Dodd-Frank Act does establish a new Financial Stability Oversight Council, a coordinating mechanism chaired by the Treasury. However, the regulatory landscape has been little changed. The result is that, following Dodd-Frank, we are left with a half-dozen distinct regulatory agencies involved in banking and finance, each with its own mandate, its own institutional loyalties and support networks in Congress, along with an ever-growing cadre of lobbyists equipped with the capacity to provide campaign financing.

I will not take the time to elaborate on all of the evident frictions and overlapping responsibilities. But here we are, almost three years after the passage of Dodd-Frank, with important regulatory and supervisory issues arising from the act unresolved. Those include the prohibition on proprietary trading by banks—especially close to my heart—and certain aspects of trading of derivatives.

Beyond Dodd-Frank, a seeming consensus among the agencies and the Treasury on reform of money market mutual funds still has not resulted in satisfactory action even though no new legislation is required. A recently announced proposal by the SEC has been to require mark-to-market accounting for some funds. Such accounting requires that the value of assets be based on their current market prices, and not on historical cost accounting. That proposal, if accepted, will go only part way. Similarly, progress toward international accounting standards is stalled and no meaningful reform of the credit-rating agencies has been undertaken.

I know these issues raise old questions of regulatory organization, some of them apparent fifty years ago. I also know some of the current issues are complex and call for highly technical judgments. But none of that mitigates the fact that the current lack of agreement on key regulations and their enforcement is simply unacceptable to the financial industry, as well as harmful to effective governance. We also know that the present overlaps and loopholes in Dodd-Frank and other regulations provide a wonderful obstacle course that plays into the hands of lobbyists resisting change. The end result is to undercut the market need for clarity and the broader interest of citizens and taxpayers.

The simple fact is the United States doesn’t need six financial regulatory agencies—the Fed, the SEC, the FDIC, the CFTC, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, and the Office of the Controller of the Currency. It is a recipe for indecision, neglect, and stalemate, adding up to ineffectiveness. The time has come for change.

As things stand today, I am told that can’t happen and won’t happen. However powerful the arguments for action, the vested interests—within the agencies, in Congress, and outside—are just too strong.

I ask, can we let that view stand unchallenged? Permit me to look back once more, a half a century ago, for inspiration. Then, faced with similar issues about financial markets, monetary policy, and regulation, with unanswered questions and political pressures from left and right, two special inquiries were launched. The first was by Congress itself. A few years later an extensive review entirely sponsored by the private sector was undertaken. Both were well financed and staffed, with highly responsible leaders. In the Senate, there was Senator Paul Douglas, a well-known economist, who provided leadership and chaired the inquiry by the Joint Economic Committee. Frazer Wilde, a public-spirited, highly respected insurance company executive, chaired the private Commission on Money and Credit.

I recall from my then limited perch that the Federal Reserve was, true to its name, reserved, fearing that its independence and authorities might be questioned. Moreover, it’s easy to look back and find that most of the specific and detailed recommendations of the two inquiries—including proposals to consolidate the regulatory agencies—never were acted upon.

However, something crucially important was achieved. The result was to reinforce the rationale for Fed independence at a time when that was not taken for granted. Both extreme “populist” and “liberal” views about monetary policy and the organization of the Federal Reserve were rejected. The need for adequate resources and able staff for all the regulatory agencies was strongly supported. More broadly, a growing role for active countercyclical fiscal policy was advocated when that was not yet commonly accepted.

Can we replicate that process today? Can strong ideological and political divisiveness in the present Congress be overcome, along with the baleful influence of the constant search for campaign financing? I don’t know. I do sense a risk of a quite different kind of inquiry emerging, one with a preconceived mission of limiting Federal Reserve independence, restraining needed financial regulation, and conducting radical surgery on the financial system.

Let’s reject a meat-ax approach. Much better that the president, congressional leaders, and interested and responsible business and academic experts together support something constructive: a well-coordinated, adequately financed inquiry bringing together the legitimate public and private interests.

The erosion of confidence and trust in the financial world, in the financial authorities that oversee it, and in government generally is palpable. That can’t be healthy for markets or for the regulatory community. It surely can’t be healthy for the world’s greatest democracy, now challenged in its role of political and economic leadership.

Instead of complaining, let’s do something about it—something that can in its own way help restore a sense of trust and confidence that is so lacking today.