It’s called “the French paradox.” On the one hand the Germans, with the assistance of the actively anti-Semitic Vichy government and of a certain number of actively anti-Semitic French citizens, deported a shocking number of the Jews living in France between 1940 and 1944 to their deaths. On the other hand, the proportion of Jews deported from France was much smaller than that deported from the Netherlands, Belgium, or Norway. Is it not curious that among the Nazi-dominated countries of Western Europe the country reputedly most anti-Semitic had one of the highest survival rates? In that region only Denmark and Italy lost a lower proportion of their Jewish population.

About a quarter of the Jews who were living in France between 1942, when the deportations began, and 1944 were murdered. Double that proportion—roughly half—of the Jews living in Belgium and Norway during the same period were killed. The loss in the Netherlands was a catastrophic 73 percent. Why such disparities? What set France apart?

Jacques Semelin contends that the answer is assistance by French individuals, along with voluntary organizations, both Jewish and non-Jewish, rooted in a generally sympathetic public opinion. Much of his long book consists of a detailed analysis of the manifold ways Jews survived in France, either by their own ingenuity or with the aid of others, during the deportation period: from the first train, on March 27, 1942, to the last, on August 17, 1944. The basic raw material consists of personal testimonies: diaries or notes kept during the occupation period by six persons (not all of whom survived) plus postwar written and/or verbal testimonies by seventeen survivors: ten French citizens and seven foreign or stateless Jews who lived in France. About sixty other eyewitness statements are used to illustrate particular points.

Rescue efforts undoubtedly helped save many thousands of Jewish lives in occupied France. It is impossible to determine an exact number, of course, because some of the people involved were no longer living when studies were carried out, or did not care to speak about that painful time. A total of 3,654 French people have been inscribed as “Righteous Among the Nations” at the Yad Vashem Memorial in Jerusalem, as non-Jewish persons who aided Jews in danger of death at some risk to themselves, in third place behind only Poland and the Netherlands. The French government has proudly memorialized them with a plaque in the Pantheon. That number is surely only a small sample.

But did French people aid Jews more frequently than other Western Europeans? Semelin never says so outright, to be sure, yet he seems to imply as much, since he claims to be looking for “traits specific to French society.” No detailed comparison of rates of rescue efforts seems to exist, but no country affected by Nazism lacked such efforts. In one German province (Düsseldorf) where police records survive, there are 203 files on Germans who aided Jews, thirty for those suspected of the same offense, and forty-two on Germans who expressed public opposition to the persecution of Jews, mostly following the events of Kristallnacht in November 1938. Surely others escaped detection.1 An early and active Belgian resistance seems to have hidden about 25,000 Jews out of a total of about 70,000, almost all foreign, likely a higher rate than in France. A late start to rescue efforts in the Netherlands enabled only about 25,000 to be hidden out of a larger total of 140,000.

Semelin defines assistance far more broadly than simply hiding people, however. He is simultaneously a scholar and a militant proponent of nonviolent resistance to dictatorships and to mass-based genocides. In Unarmed Against Hitler he wrote that “petits gestes” were more effective than armed resistance.2 Whereas the latter set off spirals of violence and reprisal without really weakening the dictator, he argues, generalized nonviolent refusals (such as those of the Dutch doctors and the Norwegian clergy) produced awkward challenges that created divisions within the occupation regimes.

The danger here is making one’s concept of resistance too broad. Even silence can be an act of resistance, if it means not reporting a hidden refugee to the Gestapo. Semelin is less convincing, however, when he includes the indifferent among the resisters. He means people who refused to be mobilized by anti-Semitic propaganda, but indifference usually means something negative, a selfish preoccupation with one’s own everyday problems to an extent that allows the dictator a free hand.

If we accept Semelin’s broad definition, aid and assistance to Jews swells in his book to become in the summer of 1942 “an important movement of social reactivity.” A section entitled “Hommage au français moyen” (In praise of the average French person) makes it sound almost unanimous. Semelin implies two questionable conclusions here—that courageous actions of assistance to threatened Jews were ordinary, and that sympathy to threatened Jews was the norm in France.

Advertisement

Semelin does not neglect the reality of French popular behavior harmful to Jews. Many denounced hidden Jews to the authorities, though Semelin quite properly rejects the figure of two or three million French informers sometimes suggested. The most careful study accounts for several hundred thousand instances in which people acted as informers during the occupation (a majority of them not against Jews).3 Despite Semelin’s gestures toward balance, however, the dark side may be hard to remember during many pages of happy outcomes, especially in view of his conviction that most of the French population was sympathetic.

The heart of the matter is French public opinion. Semelin dwells, quite appropriately, on the profoundly negative reaction of many French people to the public arrests of thousands of Jews, some forcibly separated from their children, in the summer of 1942. In Paris, on July 16–17, 1942, 13,152 foreign Jews were rounded up by French police; most of them were held for five days in a bicycle-racing stadium, the Vélodrome d’hiver, without enough food, water, or sanitary facilities, before being deported to the new extermination center in Nazi-occupied Poland, Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In the unoccupied zone, between August 6 and September 15, 1942, the Vichy authorities rounded up or took from refugee camps slightly more than ten thousand foreign Jews, transported them to the occupied zone, and handed them over to the German authorities there. This action, taken at Vichy’s own initiative, was particularly shocking since it meant that French police delivered Jews to the Nazis from an area outside German occupation. There was no other case like this in Western Europe, and few in Eastern Europe.4

The strong public revulsion these actions aroused is well documented in police reports and other contemporary documents. Five bishops denounced them from the pulpit (though they blamed the Germans, and a majority of the French bishops remained silent). That individual and group actions to save Jews, especially children, became widespread in France starting in the summer of 1942 is beyond dispute.

But what about French opinion of Jews before that turning point, between the defeat of 1940 and the summer of 1942? Semelin thinks that if so many French people responded to the arrests of summer 1942 with outrage and assistance, the degree of anti-Semitism in France between 1940 and 1942 must have been exaggerated. His evidence to the contrary is the diaries and testimonies of Jews who had fortunate outcomes. These witnesses recalled the sympathetic French people who helped them. But a companion volume based on testimonies from the doomed, if such could be found, would evoke rather different French people: the betrayers of hidden Jews who wanted to obtain an apartment or get rid of a competitor; the bounty hunters paid by the head for Jews turned over to the Gestapo; some 50,000 purchasers of Jewish properties at less than real value, often neighbors; zealous officials of Vichy’s Police aux Questions Juives or the Milice; magistrates who judged Jews more harshly than others in petty criminal cases.5

Semelin rejects the kinds of evidence that most scholars have used to assess French public opinion: the monthly reports by the prefect of each department, based on the prefects’ personal knowledge as well as on clandestine police scrutiny of mail and telephone conversations. Contrary to Semelin’s assertion that the prefects reported what their boss, the minister of the interior, wanted to hear, the prefects had strong motivations to report accurately so that the minister of the interior might not receive an unpleasant surprise later on. Notably, the prefects told Interior Minister Pierre Laval that his speech of June 22, 1942, expressing hope for German victory because otherwise Bolshevism would triumph had been very badly received.

The most authoritative work on French public opinion during the occupation relies upon the prefects’ reports, and concludes that in 1940 anti-Semitism “impregnated a large part of the French population, right and left, among Catholics, in every profession.”6 Semelin admits the existence of French popular anti-Semitism, especially following the defeat of 1940, but he is convinced that it was readily outweighed by compassion. This is surely the most controversial aspect of his book.

Human aid was not the only thing that helped Jews survive in France. The broad expanses of thinly populated rural France offered more opportunities for dispersal and concealment than were available in the Low Countries. One could melt into the French population if one spoke French well enough. Most children of Jewish immigrants did, for Vichy did not have a policy of expelling them from school (with the significant exception of Algeria). Fascist Italy, by contrast, removed all Jewish children from public schools in 1938.

It helped in France if one bore no resemblance to abstract images of the shtetl Jew. Resourceful individual Jews could pursue a host of strategems to save themselves in France, often aided by neighbors or even by officials. The existence of an unoccupied zone in southern France should have made things easier until it was occupied in November 1942, but Vichy sent the ten thousand foreign Jews already mentioned from the unoccupied zone into Nazi hands, including children younger than the Nazis wanted to receive. Semelin thinks that having French offi- cials in place was advantageous, but the Germans governed through local offi- cials in every occupation regime in West- ern Europe. If the French officials were sympathetic to Jews this would help, but that was only sometimes the case.

Advertisement

A more important advantage of the French unoccupied zone was the relative freedom enjoyed there, at least for a time, by nongovernmental relief organizations. Many of these had religious ties, particularly Jewish (the Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants and the international emigration agency HICEM) and Protestant (the Quakers and the French Protestant aid organization CIMADE). Money came from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and from the twenty-five-member Coordinating Committee at Nîmes, directed by the American YMCA official Donald Lowrie.

Some foreign individuals, such as Suzanne Spaak, the wealthy sister-in-law of the Belgian statesman, and the American Varian Fry, were able to organize rescue work in unoccupied France for a time. As for the official Union générale des Israélites de France, funded by money confiscated from French Jewish charities and individuals, it furnished some aid and shelter but later became a trap when its orphanages and offices were raided by the Gestapo. The open role of NGOs in Jewish relief and rescue was another special feature of the French unoccupied zone, and Semelin does not ignore it. In Central and Eastern Europe, by contrast, it was mainly pity by individual gentiles that saved some Jewish children.

Though Semelin identifies and investigates with great care the range of aid and survival strategies, he does not investigate the German side of the picture. Nazi extermination officials tended to focus their attention on one region at a time, and sometimes they lacked trains. Variations in Nazi exterminationist activity need to be examined further and taken into account.

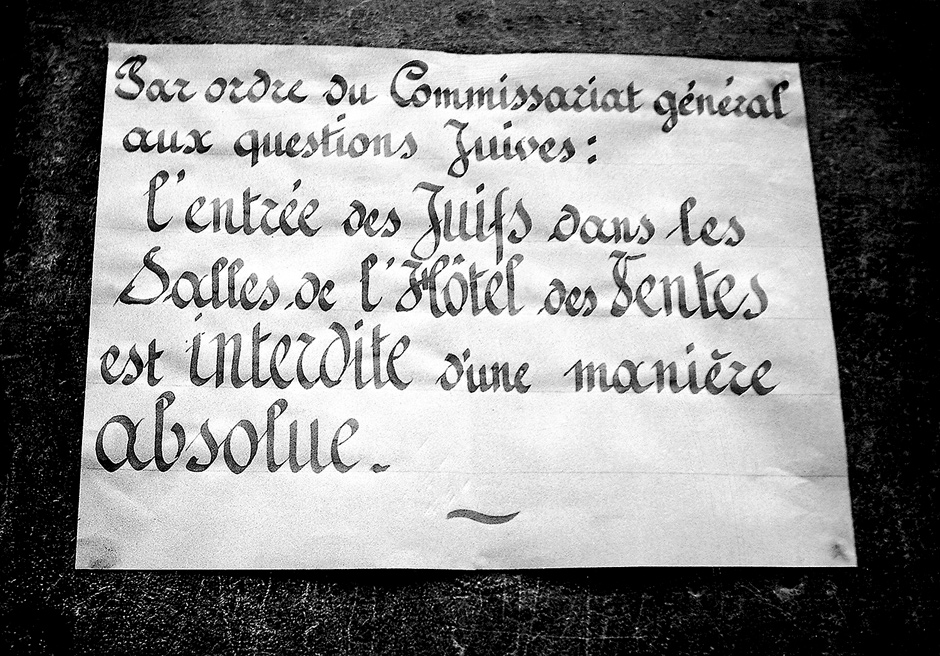

The “French paradox” has sometimes been used as an alibi to claim that things weren’t as bad for Jews in Vichy France as has been claimed by hostile or foreign observers. The first person to do so was Xavier Vallat, the head of the Commissariat aux Questions juives at Vichy in 1941–1942. At his trial for collaboration in December 1947, Vallat claimed that by taking its own steps to resolve the “Jewish problem” in France instead of leaving everything to the Germans, the Vichy government had saved 95 percent of the Jews who had French citizenship (87 to 88 percent is nearer the truth).7 The unrepentant Vallat also predicted that the United States, too, would soon have to face its own “Jewish problem.”8

Vallat’s defense is undermined by the way Vichy legislated against French Jews as well as against foreign Jews. All Jews in France, native-born or foreign-born, suffered exclusions from public employment, quotas in education and the professions, confiscations of property, and the fatal requirement to register. The first two deportation trains in spring 1942 contained French as well as foreign Jews, and Vichy did not protest. When, in the summer of 1942, the Vichy authorities began to try to limit the deportations to foreign Jews, it was too late to undo the damage Vichy had already done to French Jews. In the end about 24,500 Jews of French citizenship were deported to their deaths. This may be a small percentage of an unknown but large total, approximately 12–13 percent, but in absolute terms it is a shocking figure.9 As for Jews who immigrated to France just before the war, about half (55,000) were killed, a result that approaches the Belgian rate.

Vallat’s case is weakened further by the fact that it was on their own initiative that the German authorities in Belgium also spared Jews of Belgian nationality at first, in order to minimize public opposition. No national government existed inside Belgium to urge them to do so.

Even some present-day authors try to use the “French paradox” to make a positive case for Vichy. The latest example is Alain Michel’s Vichy et la Shoah: enquête sur le paradoxe français, a work Semelin denounces as an effort to “rehabilitate” Vichy.10 Semelin emphatically denies any intention to present a rose-colored history of Vichy France. But while he judges the Vichy state harshly, he wants to modify the current image of the French population during the occupation, which he considers excessively negative (this reviewer receives some blame for it). The proof, for Semelin, is the surprising number of survivors who went openly about their business in France, protected, he argues, by a general climate of sympathy.

The essential background to Vichy’s readiness to send foreign Jews back to Germany is the flood of refugees France received in the 1930s. Today we can hardly avoid seeing Vichy’s measures as part of the first stage of the Holocaust; it is more historically accurate to see them as the last stage of a refugee crisis. In 1939, with 7 percent of the population foreign-born, France was obsessed with its perceived burden of refugees and immigrants. Semelin writes that in the 1930s, France had been “the first immigrant country [proportionally] in the world,” at a time when the United States refused to enlarge its immigration quotas by one iota to accommodate Jewish flight from Central Europe.

Negative reactions followed. Some (not all) French people saw the Jewish immigrants as competitors for jobs made scarce by the Great Depression; as diluters of French culture already threatened by Hollywood and jazz; and above all, in 1940, as promoters of “la guerre juive”—the dreaded war against Hitler. The refugee crisis did not end with the defeat of 1940; during the following fall and winter, German authorities expelled over six thousand German Jews into unoccupied France, despite Vichy’s vigorous protests. The hostility to refugees explains why just after the defeat of 1940 many (though not all) French people wanted and expected government measures to reduce Jewish influence and to send the refugees elsewhere. Even some Resistance movements thought that France had “a Jewish problem.”11 Semelin’s account of French public opinion toward Jews in 1940 underplays the emotional effects of the antagonism toward refugees during the 1930s.

Some of Semelin’s most interesting pages concern cases where conventionally anti-Semitic attitudes did not prevent some French people from helping Jews. Some rescuers, like the curmudgeon played by Michel Simon in the 1967 film Le vieil homme et l’enfant, did not know that the needy people—especially children—were Jews. Aid came more easily when the refugee could help work on the farm, and when the host was paid. Semelin is particularly informative about the ways that sheltering needy Jewish children fit comfortably within a well-established French rural practice of taking in the children of the Assistance Publique in exchange for a small stipend and some farm work.

Comparison lies at the heart of Semelin’s enterprise. He rules out, however, the most interesting comparison: Fascist Italy. Like France, Italy was only partially occupied by the Germans; both countries had official links to Nazi Germany—Italy by alliance and France, more coercively, by an armistice; like Vichy France, Italy adopted its own measures of discrimination against Jews and applied them thoroughly. The two cases had much in common. Only 16 percent of the Jews of Italy were deported (Semelin, usually so precise, says 20 percent). Whereas comparison with the Low Countries and Norway makes France look good, comparison with Italy makes France look bad.

Semelin rejects the Italian comparison because, he writes, the Germans occupied Italy later than they occupied France. But the German occupation of Italy in September 1943 came only ten months after the German occupation of the formerly unoccupied zone of southern France in November 1942. Moreover Italy, or at least northern Italy, remained occupied eight months longer than France, until early May 1945. Some deportation trains left Italy in 1945, long after the last ones left France in August 1944. The occupation of northern Italy was thus only two months shorter than that of southern France, though, to be sure, northern France (and not Italy) was occupied during the crucial year of 1942. And Germany did not need to occupy southern France since the Vichy government itself handed over Jews from that region.

Time, moreover, was not the most important variable. It took the Nazis and their Hungarian helpers only three months to deport 450,000 Jews from Hungary between April and July 1944. A recent authoritative comparative study shows that the most important variable was the concentration of Nazi effort.12

The next most important variable was the degree of police and para-police cooperation. In Belgium, 67 percent of the Jewish population of Antwerp was deported as compared with 37 percent from Brussels, largely due to the active assistance of the Flemish nationalist Volkswering (People’s Defense) in Antwerp.

In the Italian case police cooperation was desultory. To be sure, some Italian Fascist militiamen helped the Nazis hunt down Jews; it was they who arrested Primo Levi, for example, on December 13, 1943. But the public largely refused to help them, and much of the administration dragged its feet. Aid to Jews by the clergy was considerable in both countries, even without any overt encouragement from Pope Pius XII. It is plausible, though admittedly speculative, to think that the French figure would be closer to the Italian figure of 16 percent without the negative effect of actions taken by the Vichy state and by some French anti-Semites.

Nazi effort was particularly intense in the Netherlands. As a kindred Germanic people, the Dutch had the dubious honor of being ruled not by military authorities, like Belgium and France, but by a committed Nazi civilian, the Viennese lawyer Arthur Seyss-Inquart. Nazi party and SS officials took charge of occupation policy in the Netherlands from the beginning, whereas the SS assumed direct control of police and racial programs in France and Belgium only in May 1942. Therefore it did not make much difference in the end that the Dutch people rejected Nazi racism more actively than any other Western occupied nation. The population of Amsterdam went on strike in February 1941 against the first measures taken to eliminate Jews from professions and businesses. Students struck to protest the removal of Jewish professors. Another widespread strike against Nazi measures took place in April and May 1943. In each instance the Nazi authorities reacted with savage reprisals, closing the universities entirely and sending hundreds of Dutch civilians and students to speedy deaths in the notorious Mauthausen quarry in Austria. Public protests actually made things worse; the Nazis responded to Dutch clerical protests by immediately deporting all converts of Jewish origin.

Some commentators speak of a “Dutch paradox”—a tolerant country where the final results were worse than those of Hungary. Crucial to the Nazi success in the Netherlands was the behavior of Dutch officials called the secretaries-general, who had been left in charge of each ministry when Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government went to London in June 1940. As German pressures increased, the secretaries-general adopted a policy of “presence”—including participation in the roundup of Jews—in order to keep the administration in Dutch hands.

Another crucial step was the swamping of the Dutch police by large numbers of indigenous Nazis, members of Anton Adriaan Mussert’s Dutch National Socialist Movement. Given the efficiency of the Dutch administration—their ID card was all but impossible to forge, unlike the French ones for which a wine cork could be carved into a plausible stamp—as well as the orderly and obedient nature of Dutch society, and a late start to rescue efforts, the result was a death toll in the Netherlands among the highest in all of Europe.

The Belgians, too, rejected Nazi anti-Jewish measures more overtly than the French. The Belgian resistance stopped a deportation train on April 19, 1943; the mayors of Brussels refused to distribute the yellow star that Jews were required to wear after May 27, 1942. The Vichy regime, it is true, rejected the yellow star in the unoccupied zone, arguing successfully that it was contrary to the German interest to so flagrantly undermine Vichy’s appearance of sovereignty. In the occupied zone, however, the French administration distributed the star, enforced its wearing, and helped arrest those brave French gentiles who mocked the new rule by wearing a version of the stars.

Jacques Semelin wrote his book with good intentions, describing the very real rescue efforts of some French people during the Holocaust, even as other French people aided those efforts and an even larger number had time only for their own struggle to survive a bitter enemy occupation. Serge Klarsfeld, the principal memorializer of the Holocaust in France, has long accused the Vichy state and defended the French population in ways quite similar to those of Semelin. The Vichy state “dishonored itself in contributing efficaciously to the loss of a quarter of the Jewish population of this country,” Klarsfeld wrote twenty years ago. But the remaining three quarters “owe their survival essentially to the sincere sympathy of most French people, and to their active solidarity as soon as they understood that Jews who fell into German hands were condemned to death.”13

Semelin has approached this sensitive matter with care and scholarly accuracy. But the balance he wanted to adjust remains off kilter. There is a troubling tone of satisfaction in the subtitle—“how 75 percent of the Jews of France escaped death.” Semelin claims that the French population inflicted a “half-failure” (“semi-échec”) on the Nazi Final Solution. What he fails to say is that the actions of the Vichy state and its accomplices in the French population made the result worse than it would have been without them.

-

1

See Sarah Gordon, Hitler, the Germans, and the “Jewish Problem” (Princeton University Press, 1984), pp. 211–215. ↩

-

2

Praeger, 1993. Other works in a similar vein by Jacques Semelin include Resisting Genocide: The Multiple Forms of Rescue, edited with Claire Andrieu and Sarah Gensburger (Columbia University Press, 2011) and Résistance civile et totalitarisme (Paris: André Versaille, 2011). ↩

-

3

Laurent Joly, La Délation dans la France des années noires (Paris: Perrin, 2012), p. 12. ↩

-

4

Romania handed over Jews from Russian territories they invaded, or killed them outright. Hungary handed over some Jews from Russian territory. Slovakia delivered its own Jews to Nazi forces in Poland although it was not occupied. Bulgaria (whose record otherwise was good) handed over Jews in captured areas of Thrace and Macedonia. ↩

-

5

The nearly universal severity of French magistrates toward Jews in criminal courts has been recently demonstrated by Virginie Sansico, “‘Mon seul défaut est d’être de race juive’: La répression judiciaire contre les Juifs sous le régime de Vichy,” in Pour une microhistoire de la Shoah, edited by Claire Zalc, Tal Bruttmann, Ivan Ermakoff, and Nicolas Mariot (Paris: Le genre humain/Éditions du Seuil, 2012), pp. 265–284. ↩

-

6

Pierre Laborie, L’Opinion française sous Vichy (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1990), p. 134. Semelin otherwise praises Pierre Laborie’s work. ↩

-

7

Le procès de Xavier Vallat présenté par ses amis (Paris: Éditions du Conquistador, 1948), p. 118. ↩

-

8

Xavier Vallat, Le Nez de Cléopâtre: Souvenirs d’un Homme de droite, 1919–1944 (Paris: Les Quatre Fils Aymon, 1957), p. 257. ↩

-

9

No one knows exactly how many Jews were living in France in 1940 because French statistics do not indicate religious or ethnic affiliation. The usual estimate is 300,000–330,000. Therefore, although we know that 80,000 Jews living in France died in the Holocaust, thanks to the relentless enquiries of Serge Klarsfeld, we cannot establish precisely what percentage of the total that figure represents. ↩

-

10

Alain Michel, Vichy et la Shoah: Enquête sur le paradoxe français (Paris: Cld Éditions, 2012). ↩

-

11

Renée Poznanski gave this matter magisterial treatment in Propagandes et Persécutions: La Résistance et le “problème juif,” 1940–1944 (Paris: Fayard, 2008). See especially pp. 124–129, 144, 181, 194–196, 203, 240–244. ↩

-

12

Marnix Croes, “The Holocaust in the Netherlands and the Rate of Jewish Survival,” Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Vol. 20, No. 3 (Winter 2006). ↩

-

13

Serge Klarsfeld, Le Calendrier de la persécution des juifs de France, 1940–1944 (Paris: Les Fils et Filles des Déportés Juifs de France, 1993), p. 1103. ↩