Around 1600, a dramatic shift took place in Mughal art. The Mughal emperors of India were the most powerful monarchs of their day—at the beginning of the seventeenth century, they ruled over a hundred million subjects, five times the number administered by their only rivals, the Ottomans. Much of the painting that took place in the ateliers of the first Mughal emperors was effectively dynastic propaganda, and gloried in the Mughals’ pomp and prestige. Illustrated copies were produced of the diaries of Babur, the conqueror who first brought the Muslim dynasty of the Mughal emperors to India in 1526, as well as exquisite paintings illustrating every significant episode in the biography of his grandson, Akbar.

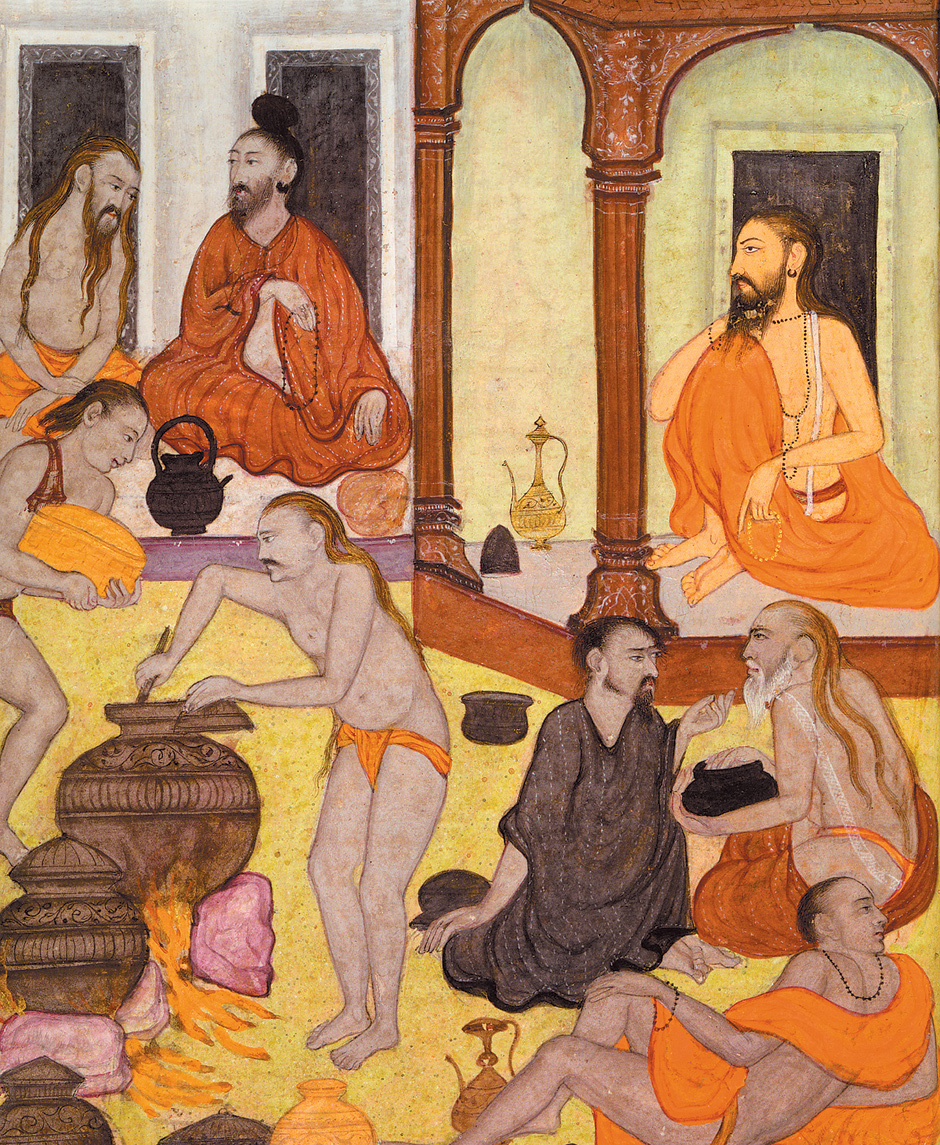

Then, quite suddenly, at this moment of imperial climax, a young Hindu khanazad (or “palace-born”) prodigy named Govardhan began painting images of a sort that had never been seen before in Mughal art. They were not pictures of battles or court receptions. Instead they were closely observed portraits of holy men performing yogic asanas or exercises that aimed to focus the mind and achieve spiritual liberation and transcendence. The results of Govardhan’s experiments in painting—along with a superbly curated selection of several hundred other images from the history of yoga—were recently on view in “Yoga: The Art of Transformation,” a remarkable exhibition at the Freer and Sackler galleries in Washington, D.C., which will travel next to San Francisco and Cleveland.

Govardhan’s images of holy men are works of penetrating intensity. They use the same skills of characterization and portraiture that the artist had learned from his close study of the Renaissance gospel books brought to India by the Jesuits. These portraits are as beautifully drawn and observed as anything Govardhan had painted before, with carefully stippled faces and the artist’s characteristically precise delineation of the subjects’ noses and cheekbones. But they are no longer the familiar courtiers or princes, seekers of power or pleasure. Instead these humble sadhus outside their huts, hair matted, limbs entwined, are engaged in a much harder quest: the long and arduous journey toward enlightenment.

The reasons behind this radical shift lay partly in geography and partly in politics. In the early months of the seventeenth century Crown Prince Salim, the future emperor Jahangir, had rebelled against his father Akbar. While the emperor was distracted by his attack on the Sultanate of Ahmadnagar to the south, Salim came close to setting himself up as a rival emperor in the north, making his own appointments and running his own imperial administration. It was exactly during the period of Salim’s rebellion, from early 1600 to November 1604, that Govardhan’s art underwent its transformation.

The place Salim chose as his power base was Allahabad, previously known as Prayag. This was one of the most sacred places in India for Hindus: the point at which the two holy rivers of the north, the Yamuna and the Ganga, come into confluence. Prayag has always been a place of congregation for holy men, and in the seventeenth century it seems as if the great ascetic gathering we know today as the Kumbh Mela took place there as regularly as every five years, not on the current twelve-year cycle.

The Kumbh remains even today one of the most extraordinary sights on earth. Overnight a provincial town is transformed into a heaving ascetic metropolis, larger than London or New York. Hundreds of thousands of sadhus and yogis of the rival Hindu orders—Shaivite seekers with their tridents, Vaishnavite Ramanandis, and Nath yogis—pour in, with their dreadlocked hair and wild, often unpredictable behavior. Some are freelance wanderers, moving from town to town; others live ordered monastic lives in ashrams, dividing their day according to strict rules and performing severe penances. Most hypnotic of all are the unruly and aggressive naga sadhus: the naked, ash-smeared warrior ascetics who have always formed the shock troops of Hinduism.

There was nothing new about Prince Salim’s interest in this ascetic world. Far from being excluded by the Mughals, Hindu mysticism and its affinities with the austerities of Sufism had been a focus of Islamic interest in India since before the first Muslim conquests of the twelfth century. Half a millennium earlier, the Central Asian Muslim scholar Alberuni, who died in 1048, was the great pioneer of Hindu-Muslim interaction, and translated into Persian what are often regarded as the foundational texts of yoga, the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (second to fourth century AD). Two hundred years later, one of the most important Indian Sufis, Mu’in al-Din Chisti (died 1236), was credited with the authorship of an encyclopedic work entitled Treatise on Nature of Yoga, which again stressed the compatibility of Islamic and Hindu mysticism.

Advertisement

By the sixteenth century, yoga and the secret bodies of knowledge that were associated with it had become part of the science of government in Indo-Islamic courts. The interest was as much practical as mystical: many sultans were convinced that extraordinary powers could be accessed through the practices of yogis.

It was during the reigns of the enquiring emperor Akbar and his son Salim that this interest took on a new urgency. Akbar had the Yoga Sutras and several other ancient Hindu texts on asceticism translated or summarized. His biographer Abul Fazl wrote with wonder about yogic asanas, remarking that “the writer of these pages, who has witnessed many of these postures, has gazed in astonishment, wondering how any human being could subject his muscles, tendons and bones in this manner to his will.”

In addition, a new work, Bahr al-Hayat (The Ocean of Life), was composed around 1550 by Muhammad Gwaliyari, a prominent Sufi shaykh who was close to Akbar’s court. He wanted his disciples to learn hatha yogic practices.* In the form that Salim commissioned it, The Ocean of Life constitutes the earliest-known treatise to contain a systematic series of images of yoga postures. Twenty-two different asanas—almost all seated postures designed to aid meditation—are examined. It is clear from the images that the artists that Salim had lured to Allahabad, Govardhan preeminent among them, must have been sent down to the confluence of the holy rivers to talk to and interact directly with yogis engaged in their austerities below the palace walls.

A portrait survives of Govardhan at this time: it shows an eager, sharp-eyed, and intelligent young man with raffishly long sideburns and a carefully trimmed mustache, dressed in an immaculate white robe and dashing black cape. Govardhan knew he was the crown prince’s particular protégé, and in years to come proudly referred to himself as “the servant of Shah Jahangir.” How this dapper young courtier got on with the dreadlocked holy men is not recorded; but the result is a revelation, perhaps the most intense artistic interaction that survives between Hindu and Islamic worlds. We are now far away from the idealized world of court art. Instead the illustrations show ash-smeared holy men engaged in their yogic austerities outside their huts with an almost photojournalistic accuracy.

The images are lightly colored, with translucent washes, showing every detail of the yogis’ daily lives, from their postures and pensive expressions through the form of their huts down to their pet dogs and smallest possessions: their horn whistles, staffs, gourds, and ewers, even the antelope skins they use for yoga mats. Most intriguing of all is the image of one holy man whose body may be drawn from life but whose face is quite clearly borrowed from that of Christ in some European gospel book.

So it was that seventeenth-century Allahabad/Prayag became the confluence not just of two holy rivers but of several traditions of sacred art in a way that today might be considered implausible to anyone who takes at face value the idea of a clash of civilizations: a Hindu artist painting the first-ever systematic set of illustrations of yogic asana positions, while working for a Muslim patron, and borrowing for the yogis the features of Jesus Christ.

The yogic traditions that so intrigued these Islamic rulers, and that today represent the most successful Indian export into the global marketplace of spirituality, have their origins in the deepest roots of Indian civilization, predating by two thousand years the revelations of the Koran. The Sanskrit word yoga means “union” and is etymologically linked to the English word “yoke.” Its earliest occurrence in the Rig Veda, which dates from the second millennium BCE when both the Pyramids and Stonehenge were still in use, links the word to the rig with which war chariots were yoked to horses; by the early centuries AD the same word is being used to convey the idea of the body and the senses being yoked and reined in so as to move toward the Absolute.

It is possible that the oldest image in Indian art shows a yogi in meditation: one of the Indus Valley seals dug up at Mohenjo Daro by Sir John Marshall in 1931, dating from between 2600 and 1900 BC, shows a cross-legged figure that Marshall interpreted to be Shiva as Mahayogi and Lord of the Beasts. This interpretation has been questioned by some scholars, but the Vedas, which date from maybe five hundred years after the Indus Valley seal, already contain references to flying long-haired sages that indicate even then the presence of a mystical tradition related to the world of the yogis.

Between the third and fifth centuries BC, yogic techniques and goals spread so as to become practiced across northern India, and were eventually codified in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali that date from the fourth century AD. By that time, yoga was being used by men and women across South Asia who sought by perfecting their bodies to transcend suffering, renouncing the world and devoting themselves to breath control, meditation, and austerities. Their radical insight was to realize that they had within them the potential correctly to perceive reality and stabilize their minds and bodies through the use of esoteric yogic techniques.

Advertisement

The Sackler exhibition explores the visual culture of yoga in all its rich variety, aiming, according to its curator Debra Diamond, to show “yoga’s rich, protean diversity—its varied meanings for both practioners and those who encountered and interacted with them—over the last 2,500 years.” For as the exhibition makes clear, while the use of meditation, posture, and breathing techniques has been widespread in India since remote antiquity, yoga was never a unified construct and has clearly meant quite different things at different times to different people, whether Jain, Buddhist, Sufi, or Hindu.

Moreover, there has always been a clear duality visible in the objectives of the yogis. Some were focused entirely on the interior: on breathing exercises and mastery of the body as a route to self-understanding and spiritual liberation. Others, however, were clearly searching for the magical tantric powers that they believed yoga could unleash. There are hints of this tension already in the Yoga Sutras where Patanjali outlines the route to union with the Absolute, while making it clear that an accomplished yogi can perform all sorts of useful tricks in this life: flying, transmigrating, reading other people’s minds, and even defying death itself.

The Khecarividya of Adinatha, an early hatha yoga text that dates from 1400 AD, which has recently been translated into English for the first time by James Mallinson, goes further and explictly promises to give the adept magical powers and ultimately immortality. “One becomes ageless and undying in this world,” writes Adinatha, “all obstacles are destroyed, the gods are pleased and, without doubt, wrinkles and grey hair will disappear.”

This is not all:

Success in sciences such as finding buried treasure, entering subterranean realms, controlling the earth and alchemy arise for the yogis after five years…. With a body as incorruptible as diamond [he] lives for one hundred thousand years. With the strength of ten thousand elephants,…he has long-distance sight and hearing. Capable of punishing and rewarding [people], he becomes powerful.

If he so wishes he can “associate at will with great ghouls, ghosts, snakes and demons.”

The text also promises attainment of “absolutely all the magical powers that are found in the three worlds,…power over zombies…and power over male and female genies.” Finally the adept can gain “dominion over the highest gods.” It is in many ways closer to the world of Harry Potter and Lord Voldemort than to the New Agey yoga of modern Western gyms, moving across a line from the search for spiritual liberation to a quest for dark and possibly demonic powers for use in this material world.

San Antonio Museum of Art

‘Yogini’; sandstone statue, Kannauj, Uttar Pradesh, first half of the eleventh century. William Dalrymple writes that ‘in ancient India yoginis were understood to be the terrifying female embodiments of yogic powers who could travel through the sky and be summoned up by devotees who dared to attempt harnessing their powers.’

This sense of shifting meaning and elusiveness of definition, around both the concept and practice of yoga over two millennia, is a difficulty that the exhibition embraces with creativity. As you enter, the first hall has on one side a white marble image of ice-calm tranquillity: a Jain Jina, or Victorious One, sitting in a lotus position, lost in peaceful meditation. Opposite it, however, is a no less fabulous image that is all sound and fury: a full-breasted and slim-waisted Hindu yogini, arriving on the back of an owl, armed to the teeth, brandishing a sword and a shield, while making a piercing wolf whistle: not for nothing does her name translate as “She Who Makes a Loud Noise.”

Today in modern India a yogini is understood to be a female yogi, a seeker after peace and enlightenment. But in ancient India yoginis were understood to be the terrifying female embodiments of yogic powers who could travel through the sky and be summoned up by devotees who dared to attempt harnessing their powers. They were also the policewomen of the yogic world, who Adinatha says will quickly eat up “he who makes this supreme text public to all…at the order of Síva.”

This dual world of the yogi is there throughout the show: for every ivory of a gentle Buddha mortifying his flesh and starving himself in the quest for inner peace and Enlightenment there are other more unsettling images of wild-looking yogis and the fearsome blood-drinking deities they sought to worship sitting amid the smoking pyres of cremation grounds, both draped with skull necklaces and brandishing weapons as they sit astride headless corpses. Some deities bring this duality into a strange union: one Himalayan image of the God Bhairava in yogic attire is wearing a belt of human arm and has a necklace, bracelets, anklets, and earrings all made of human skulls—but he is smiling as sweetly and alluringly as a baby Krishna. As one of the contributors to the catalog, David Gordon White, asks: “If these be yogis, then what is yoga?” It is something that the contributors to the exhibition catalog have clearly agreed to disagree on.

Debra Diamond, the curator of this most striking show, had as her last major project an equally wonderful exhibition of Jodhpur painting entitled “Garden and Cosmos.” That exhibition told the story of the Naths, a sect of wandering ash-smeared followers of Shiva mystics who codified hatha yoga in the twelfth century, claiming that their practices gave them superhuman powers: the ability to fly, to see into the future, and to hear and see over great distances.

By 1803, the Nath yogis were nearing the height of their influence across northern India, when they became the effective rulers of the desert kingdom of Jodhpur, advising their faithful disciple, Maharajah Man Singh, on all matters of state. In an extraordinary coup d’état, one of the greatest kingdoms in pre-colonial India had fallen into the hands of an order of esoteric yogis.

It didn’t take long before the Naths began flexing their muscles and abusing their new power: they kidnapped women and forcibly inducted men into their order, seizing property for themselves. A folk song from this period expressed the growing swell of disgust: “Nathji,” begins the chorus, “your glance is poison.” Nevertheless, it did represent a brief but astonishing golden age in the history of Rajasthani painting, and has provided some of the highlights of both the “Garden and Cosmos” show and this exhibition.

As the story of the Naths shows, yogis sometimes took very different forms from the peaceful sages the West has loved to imagine as archetypically Indian since Gandhi succeeded in presenting Hinduism to the world as the religion of ahimsa, nonviolence. This complexity is something several interesting books have recently grappled with.

In 2009 David Gordon White, a professor of religious studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, published a provocative and controversial book entitled Sinister Yogis, which took the story further. White emphasized that there is a whole tradition in South Asia of violent, frightening, and even cannibalistic yogis, many of whom had a developed taste for kidnapping children and human sacrifice. The same rites that could be used to remove the individual from his body and join it with the formless Absolute were also believed to give yogis the ability to enter another’s body, or to shift shape at will.

White made the case that medieval yogis were primarily interested in occult techniques to project the self outward in order to overcome death, enter other bodies, and effect all manner of sinister wizardry. As White shows in a book full of entertaining stories of yogis behaving badly, there is in fact a whole body of South Asian literature and folk tales where yogis are not peaceful meditators but instead archetypically wicked sorcerers.

White may well overstate his case, and James Mallinson, another of Debra Diamond’s contributors, has written critically of his work, stating that he “leaves no room for nuance,…in particular the elephant in his room—the huge body of Indic texts written over the last two thousand years which teach a meditation-based yoga.” This may well be the case, but there can be no disputing that many medieval yogis were as much in search of occult powers as cosmic self-discovery. Indeed the fascinating texts that Mallinson has himself translated show this very clearly.

Yogis seem to have gone particularly out of control during the eighteenth-century anarchy between the fall of the Mughals and the rise of the British. This is a subject explored by William Pinch in his brilliant 2006 study of the militant yogis of the period, Warrior Ascetics and Indian Empires.

European travelers of the period frequently describe yogis who are “skilled cut-throats” and professional killers. “Some of them carry a stick with a ring of iron at the base,” wrote Ludovico di Varthema of Bologna in 1508. “Others carry certain iron diskes which cut all round like razors, and they throw these with a sling when they wish to injure any person.” A century later the French jewel merchant Jean Baptiste Tavernier was describing large bodies of holy men on the march, “well armed, the majority with bows and arrows, some with muskets, and the remainder with short pikes.” By the Maratha wars of the early nineteenth century, the Anglo-Indian mercenary James Skinner was fighting alongside “10 thousand Gossains called Naggas with Rockets, and about 150 pieces of cannon.”

Pinch focuses in particular on the well-attested case of Anupgiri, a Shaivite ascetic and mercenary warlord who led a large army of killer yogis and fought with both modern weaponry and spells: Mahadji Shinde, a rival leader of the time, was convinced that Anupgiri had attacked him with a painful case of boils through his “magical arts.” Nor was Anupgiri necessarily a champion of Hindu interests: “Far from thinking of themselves as the last line of defense against foreign invaders, armed ascetics in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth century served any and all paymasters,” writes Pinch. Though he sometimes fought with the Hindu Marathas, at other times Anupgiri worked for the Mughal emperor.

Indeed in 1803 his last act, as Pinch shows, “was to enable the Maratha defeat at the hands of the British…and, thereby, the British capture of Delhi, an event that catapaulted the Hon’ble [East India] Company into the role of paramount power in southern Asia—and ultimately the world.”

Through this complex jungle of rival interpretation, Debra Diamond leads the visitor to “Yoga: The Art of Transformation” with the steady tread of the umpire.

The show opens with images of wizened ancient ascetics: Gandharan Buddhist images of lean dreadlocked sages found in the tribal areas between Pakistan and Afghanistan, and a beautiful Kashmiri ivory of the fasting Buddha. A room is devoted to a series of fabulously voluptuous flying yoginis occupying that peculiarly Indian space between the sacred, the sensual, and the utterly frightful.

Ironically it is only with the coming of the Muslims, in Indo-Islamic art, that we see for the first time what a modern practioner of yoga would recognize as an asana. But perhaps it is the yogis’ post-Mughal glory days of the eighteenth century, once thought to be a period of artistic decadence, that gives this show its highlights. The period of Nath power in Jodhpur, and Nath prominence in nearby Jaipur, led to attempts by artists in both cities to explain their understanding of the world in what are perhaps the supreme examples of the art of yoga: two vast, awesome purple-gold images of the Cosmic Body, with the sun on one eye, the moon on the other, including a representation of the relationship of the macrocosmic to the individual entitled Equivalence of the Self and the Universe.

It was under the guidance of these power-hungry Nath gurus that painting in Rajasthan transformed itself into something utterly remarkable, reaching heights of Rothko-like abstraction and mystical strangeness that predate by more than a hundred years many of the experiments of twentieth-century European and American art. Cosmic oceans of gold hint at states of heightened mystical consciousness; Mondrian-like fields of color are divided by frames of pure red; esoteric ideas take wing in sublime forms of fabulous, dreamlike intensity. Cosmic oceans lap against figures incarnating divine principles such as Purusha (Consciousness) and Prakriti (Matter). These are images that do not tell religious stories as much as attempt to explain the great questions of human existence: What are we doing here? How did we come? Who created us? Where are we going?

The penultimate room of the show examines the story of how yoga moved west between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries. From the black-and-white photographs of early British Orientalists to 1940s circus posters for “Koringa—THE ONLY FEMALE fakir IN THE WORLD,” the show ends by telling a story of cultural misunderstanding, as the complex and sometimes contradictory body of yogic knowledge was cleaned up and rebranded as a vogueish health trend open to all—men and women, Indian and foreigner—to be marketed to a sometimes credulous Western public through celebrity yoga faddists beginning with Marilyn Monroe in the 1950s. It was only at this very late point, under the influence of Swedish body building, gymnastics, and British military drill, that it became a method of fitness: almost all pre-twentieth-century Indian yoga involved staying for a prolonged period in one asana, not moving rapidly from one to another in a yogic workout.

Today it is estimated that around 20 million Americans have performed yoga. It is a fitting end to the show, therefore, that remarkable 1940s black-and-white film footage of Krishnamachrya and his youthful disciple Iyengar, inventor and exporter of Iyengar yoga, is shown in a room where visitors are encouraged to bring their yoga mats and perform their asanas within the exhibition space. They became part of one of the most stunning shows of Indian art ever to be displayed in the US.

-

*

“Hatha yoga”—“Forceful” or “willful” yoga performed with a set of physical exercises or asanas, designed to align and balance the body and mind. ↩