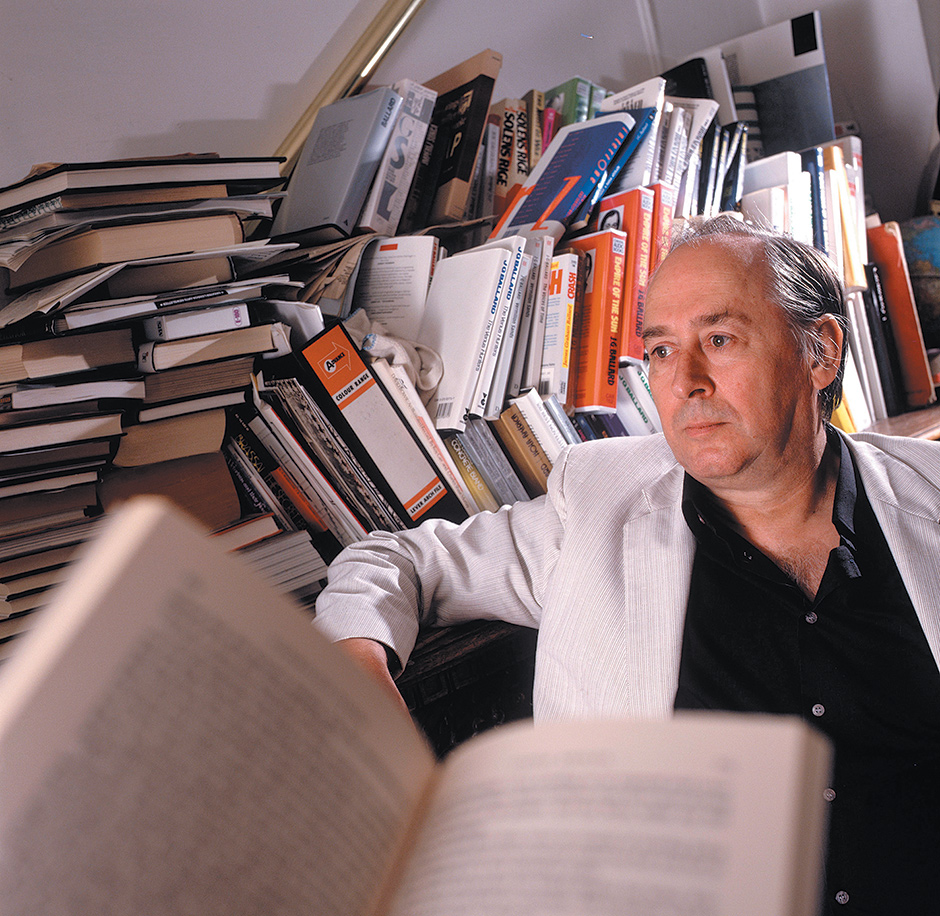

I met J.G. Ballard once—it was a car crash. We were sailing down the Thames in the middle of the night, I don’t remember why. A British Council thing, maybe? The boat was full of young British writers, many of them drunk, and a few had begun hurling a stack of cheap conference chairs over the hull into the water. I was twenty-three, had only been a young British writer for a couple of months, and can recall being very anxious about those chairs: I was not the type to rock the boat. I was too amazed to be on the boat. (Though it was no pleasure barge, more like a Travelodge afloat, with an interior that put you in mind of a Shepperton semidetached. A Ballardian boat. Everything brown and gray with accents of tube-seat orange.)

I slunk away from the chair hurlers and walked straight into Ballard. That moon of a face, the shiny tonsure, the lank side curtains of hair—ghost of a defrocked priest. An agonizing ten-minute conversation followed in which we two seemed put on earth to vivify that colloquial English phrase “cross-purposes.” Every book I championed he hated. Every film he admired I’d never seen. (We didn’t dare move on to the visual arts.) The only thing we seemed to have in common was King’s College, but as I cheerily bored him with an account of all the lovely books I’d read for my finals, I could see that moon face curdling with disgust. In the end, he stopped speaking to me altogether, leaned against a hollow Doric column, and simply stared.

I was being dull—but the trouble went deeper than that. James Graham Ballard was a man born on the inside, to the colonial class, that is, to the very marrow of British life; but he broke out of that restrictive mold and went on to establish—uniquely among his literary generation—an autonomous hinterland, not attached to the mainland in any obvious way. I meanwhile, born on the outside of it all, was hell-bent on breaking in. And so my Ballard encounter—like my encounters, up to that point, with his work—was essentially a missed encounter: ships passing in the night. I liked the Ballard of Empire of the Sun (1984) well enough, and enjoyed the few science fiction stories I’d read, but I did not understand his novels and Crash (1973) in particular had always disturbed me, first as a teenager living in the flight path of Heathrow airport, and then as a young college feminist, warring against “phallocentricism,” not at all in the mood for penises entering the leg wounds of disabled lady drivers.

What was I so afraid of? Well, firstly that West London psychogeography. I spent much of my adolescence walking through West London, climbing brute concrete stairs—over four-lane roads—to reach the houses of friends, whose windows were often black with the grime of the A41. But this all seemed perfectly natural to me, rational—even beautiful—and to read Ballard’s description of “flyovers overla[ying] one another like copulating giants, immense legs straddling each other’s backs” was to find the sentimental architecture of my childhood revealed as monstrosity:

The entire zone which defined the landscape of my life was now bounded by a continuous artificial horizon, formed by the raised parapets and embankments of the motorways and their access roads and interchanges. These encircled the vehicles below like the walls of a crater several miles in diameter.

Those lines are a perfectly accurate description of, say, Neasden along the ring road called the North Circular, but it can be shocking to be forced to look at the fond and familiar with this degree of clinical precision. (“Novelists should be like scientists,” Ballard once said, “dissecting the cadaver.”) And Ballard was in the business of taking what seems “natural”—what seems normal, familiar, and rational—and revealing its psychopathology. As has been noted many times, not least by the author himself, his gift for defamiliarization was, in part, a product of his own unusual biography:

One of the things I took from my wartime experiences was that reality was a stage set…. The comfortable day-to-day life, school, the home where one lives and all the rest of it…could be dismantled overnight.

At age fifteen, he left decimated Shanghai, where he’d spent the war, for England, to study medicine at Cambridge, and found it understandably difficult to take England seriously. This set him apart from his peers, whose habit it was to take England very seriously indeed. But if his skepticism were the only thing different about Ballard he would not be such an extraordinary writer. Think of that famous shot in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, when the camera burrows below the manicured suburban lawn to reveal the swarming, dystopian scene underneath. Ballard’s intention is similar, but more challenging. In Ballard the dystopia is not hidden under anything. Nor is it (as with so many fictional dystopias) a vision of the future. It is not the subtext. It is the text. “After this sort of thing,” asks the car crash survivor Dr. Helen Remington, “How do people manage to look at a car, let alone drive one?” But drive she does, as we all do, slowing down on motorways to ogle an accident. Like the characters in Crash we are willing participants in what Ballard called “a pandemic cataclysm that kills hundreds of thousands of people each year and injures millions.” The death drive, Thanatos, is not what drivers secretly feel, it’s what driving explicitly is.

Advertisement

“We live in a world ruled by fictions of every kind…. We live inside an enormous novel…. The fiction is already there. The writer’s task is to invent reality.” The world as text: Ballard was one of the first British novelists to apply that French theory to his own literary practice. His novels subvert in particular the world that advertising presents, with its irrational convergences sold to us as if they were not only rational but natural. In the case of the automobile, we have long been encouraged to believe there is a natural convergence between such irrational pairs as speed and self-esteem, or leather interiors and family happiness. Ballard insists upon an alternate set of convergences, of the kind we would rather suppress and ignore.

It is these perverse convergences that drive the cars in Crash, with Ballard’s most notorious creation, Dr. Robert Vaughan, at the wheel, whose “strange vision of the automobile and its real role in our lives” converges with Ballard’s own. And once we are made aware of the existence of these convergences it becomes very hard to un-see them, however much we might want to.

There is a convergence, for example, between our own soft bodies and the hardware of the dashboard: “The aggressive stylization of this mass-produced cockpit, the exaggerated mouldings of the instrument binnacles emphasized my growing sense of a new junction between my own body and the automobile.” There is a convergence between our horror of death and love of spectacle: “On the roofs of the police cars the warning lights revolved, beckoning more and more passers-by to the accident site.” And there is an acute convergence, we now know, between the concept of celebrity and the car crash:

She sat in the damaged car like a deity occupying a shrine readied for her in the blood of a minor member of her congregation…. The unique contours of her body and personality seemed to transform the crushed vehicle. Her left leg rested on the ground, the door pillar realigning both itself and the dashboard mounting to avoid her knee, almost as if the entire car had deformed itself around her figure in a gesture of homage.

This vision of a fictional Elizabeth Taylor—written twenty-five years before the death of Princess Diana—is as prescient as anything in Ballard’s science fiction. How did he get it so right? How did he know that the price we would demand, in return for our worship of the famous and beautiful (with their unique bodies and personalities), would be nothing less than the bloody sacrifice of the worshiped themselves? Oh, there were clues, of course: the myth of decapitated Jayne Mansfield, Jimmy Dean with his prophetic license plate (“Too fast to live, too young to die.”), Grace Kelly’s car penetrated by a tree. But only Ballard saw how they were all related, only he drew the line of convergence clearly. Once you see you cannot un-see. What are all the DUIs of Lindsay Lohan if not a form of macabre foreplay?

Still, it’s easy to be shocked the first time you read Ballard. I was for some reason scandalized by this convergence of sex and wheels, even though it is enshrined in various commonplaces (not to mention the phrase “sex on wheels”). What else do we imply when we say that the purchase of a motorbike represents a “mid-life crisis,” or that a large car is compensation for a lack of endowment? But of course, in the fictional version of our sexual relationship with cars, it is we, the humans, who are in control; we determine what we do in cars. In Ballard’s reality it is the other way around:

What I noticed about these affairs, which she described in an unembarrassed voice, was the presence in each one of the automobile. All had taken place within a motor-car, either in the multi-storey car-park at the airport, in the lubrication bay of her local garage at night, or in the laybys near the northern circular motorway, as if the presence of the car mediated an element which alone made sense of the sexual act.

In 1973, horrified readers condemned such passages as fantastical pornography. Thirty years later, in England, a very similar scene burst onto the front pages and even received an official term: dogging. (And at the center of that scandal was one of the biggest television stars in the country, natch.)

Advertisement

The real shock of Crash is not that people have sex in or near cars, but that technology has entered into even our most intimate human relations. Not man-as-technology-forming but technology-as-man-forming. We had hints of this, too, a long time ago, in Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto of 1909, which makes explicit the modernist desire to replace our ancient Gods and myths with the sleek lines and violent lessons of the automobile. It also features an orgasmic car crash: “When I came up—torn, filthy, and stinking—from under the capsized car, I felt the white-hot iron of joy deliciously pass through my heart!”

But Marinetti’s prose is overwrought, deliberately absurd (“We went up to the three snorting beasts, to lay amorous hands on their torrid breasts. I stretched out on my car like a corpse on its bier, but revived at once under the steering wheel, a guillotine blade that threatened my stomach”) where Ballard is calm and collected. That medic’s eye, dispassionate, ruthless:

Braced on his left elbow, he continued to work himself against the girl’s hand, as if taking part in a dance of severely stylized postures that celebrated the design and electronics, speed and direction of an advanced kind of automobile.

Marinetti’s hotheaded poets and artists wrestled with the icon of the motorcar. Ballard’s ciphers coolly appraise it. The iciness of Ballard’s style is partly a consequence of inverting the power balance between people and technology, which in turn deprives his characters of things like interiority and individual agency. They seem mass-produced, just like the things they make and buy. Certainly his narrators and narrators manqués are not concerned with the personalities of human beings:

Vaughan’s interest in myself was clearly minimal; what concerned him was not the behaviour of a 40-year-old producer of television commercials but the interaction between an anonymous individual and his car, the transits of his body across the polished cellulose panels and vinyl seating, his face silhouetted against the instrument dials.

It’s almost as if the stalker-sadist Vaughan looks at humans as walking-talking examples of that Wittgensteinian proposal “Don’t ask for the meaning; ask for the use.” When Ballard called Crash “the first pornographic novel based on technology,” he referred not only to a certain kind of content but to pornography as an organizing principle, perhaps the purest example of humans “asking for the use.” In Crash, though, the distinction between humans and things has become too small to be meaningful. In effect things are using things. (And a crazed stalker like Vaughan becomes the model for a new kind of narrative perspective.)

Now, I don’t think it can be seriously denied that some of the deadening narrative traits of pornography can be found in Crash: flatness, repetition, circularity. “Blood, semen and engine coolant” converge on several pages, and the sexual episodes repeat like trauma. But surely this flatness is deliberate; it is with the banality of our psychopathology that Ballard is concerned:

The same calm but curious gaze, as if she were still undecided how to make use of me, was fixed on my face shortly afterwards as I stopped the car on a deserted service road among the reservoirs to the west of the airport.

That seems to me a quintessential Ballardian sentence, depicting a denatured landscape in which people don’t so much communicate as exchange mass-produced gestures. (Reservoirs are to Ballard what clouds were to Wordsworth.)

Of course, it was not this lack of human interiority that created the furious moral panic around this book (and later David Cronenberg’s film). That was more about the whole idea of penetrating the wound of a disabled lady. I was in college when The Daily Mail went to war with the movie, and found myself unpleasantly aligned with the censors, my own faux feminism coexisting in a Venn diagram with their righteous indignation. We were both wrong: Crash is not about humiliating the disabled or debasing women, and in fact the Mail’s campaign is a chilling lesson in how a superficial manipulation of liberal identity politics can be used to silence a genuinely protesting voice, one that is trying to speak for us all. No one doubts that the abled use the disabled, or that men use women. But Crash is an existential book about how everybody uses everything. How everything uses everybody. And yet it is not a hopeless vision:

The silence continued. Here and there a driver shifted behind his steering wheel, trapped uncomfortably in the hot sunlight, and I had the sudden impression that the world had stopped. The wounds on my knees and chest were beacons tuned to a series of beckoning transmitters, carrying the signals, unknown to myself, which would unlock this immense stasis and free these drivers for the real destinations set for their vehicles, the paradises of the electric highway.

In Ballard’s work there is always this mix of futuristic dread and excitement, a sweet spot where dystopia and utopia converge. For we cannot say we haven’t got precisely what we dreamed of, what we always wanted, so badly. The dreams have arrived, all of them: instantaneous, global communication, virtual immersion, biotechnology. These were the dreams. And calm and curious, pointing out every new convergence, Ballard reminds us that dreams are often perverse.