1.

Compared to John Williams’s earlier novels, Augustus—the last work to be published by the author, poet, and professor whose once-neglected Stoner has become an international literary sensation in recent years—can seem like an oddity.* For one thing, it was the only one of his four novels to win significant acclaim during his lifetime: published in 1972, Augustus won the National Book Award for fiction. (Williams was born in Texas in 1922 and died in Arkansas in 1994, after a thirty-year career teaching English and creative writing at the University of Denver.)

More important, the novel’s subject—the life and history-changing career of the first emperor of Rome—seems impossibly remote from the distinctly American preoccupations of Williams’s other mature works, with their modest protagonists and pared-down narratives. Butcher’s Crossing (1960) is the story of a young Bostonian who, besotted with Emersonian Transcendentalism, goes west in 1876 to explore the “wilderness” where, he believes, lies “the central meaning he could find in all his life”; and where he participates in a savage buffalo hunt that suggests the costs of the American dream.

Stoner (1965) traces the obscure and, to all appearances, unsuccessful life of an assistant professor of English at the University of Missouri in the early and middle years of the last century—a man of desperately humble origins who sees the Academy as an “asylum,” a place where he finds at last “the kind of security and warmth that he should have been able to feel as a child in his home.” (Williams later repudiated his first novel, Nothing But the Night, published in 1948, about a dandy with psychological problems.)

It would be difficult to find a figure ostensibly less like these idealistic and, ultimately, disillusioned minor figures than the real-life world leader known to history as Augustus—a man whose many and elaborate names, given and taken, augmented and elaborated, acquired and discarded over the eight decades of his tumultuous and grandiose life, stand in almost comic contrast to the simple disyllables Williams gave those two other protagonists. Both, as readers will notice, share their creator’s name—William Andrews, William Stoner: a coincidence that makes it almost impossible not to see some element of autobiography in the early novels.

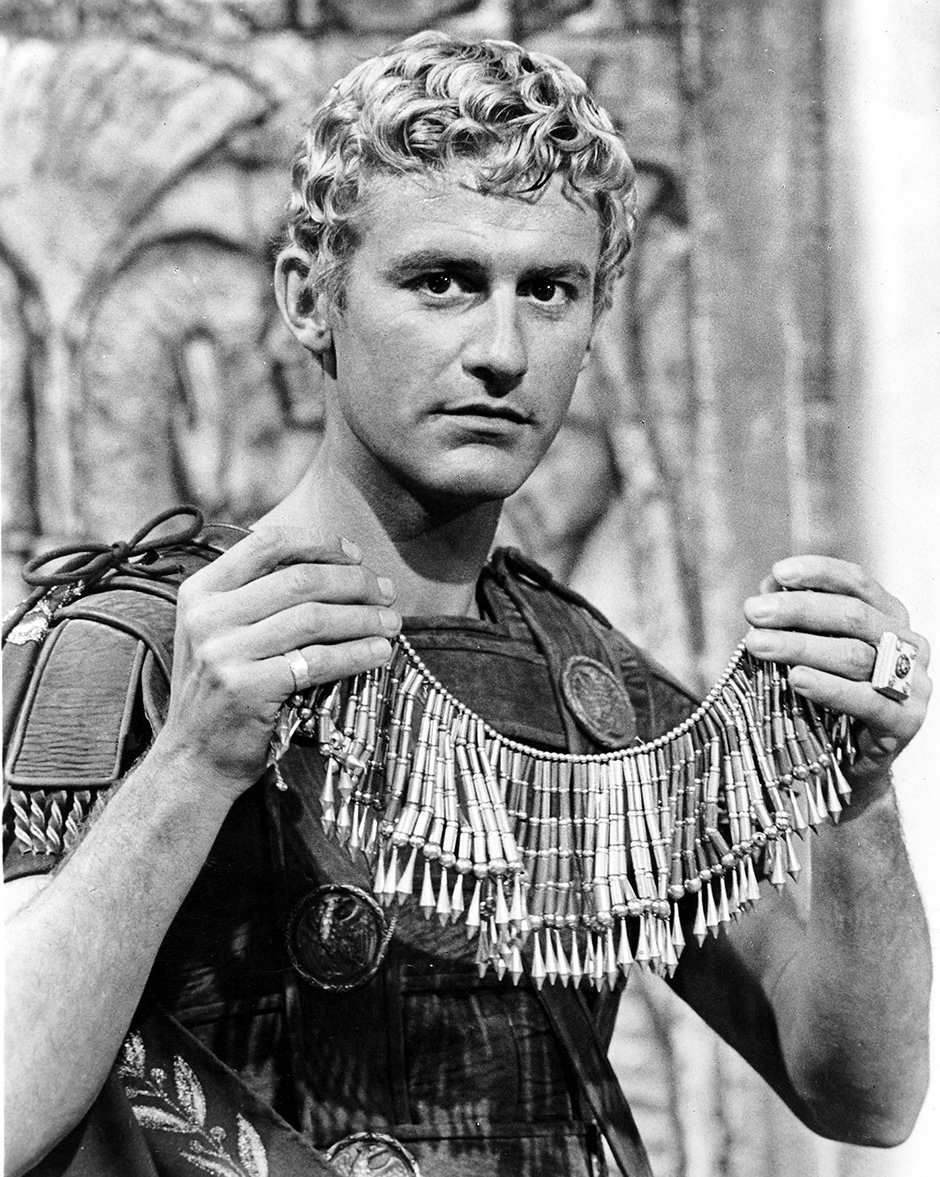

No such temptation exists in the case of Augustus. The emperor who gave his lofty name to a political and literary era was born Gaius Octavius Thurinus in 63 BC, the year in which the statesman Cicero foiled an aristocrat’s attempted coup d’état against the Republic. The offspring of Gaius Octavius, a well-to-do knight of plebeian family origins, he was raised in the provinces about twenty-five miles from Rome. While still a teenager, the sickly but clever and ambitious youth sufficiently impressed his maternal great-uncle, Julius Caesar, to be adopted by him; he was thereafter known as Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (“Octavian”).

In 44 BC, following Caesar’s assassination and his subsequent deification by decree of the Senate, the canny nineteen-year-old, eager to capitalize on his dead relative’s prestige and thereby enhance his standing with Caesar’s veterans, referred to himself as Gaius Julius Caesar Divi Filius (“Son of the Divine”). By the time he was twenty-five, having avenged Caesar’s murder by vanquishing Brutus and Cassius at Philippi, the new Gaius Julius Caesar had shrewdly maneuvered himself to the center of power in the Roman world as one of three military dictators or “triumvirs.” (Another was Marc Antony, with whom he would eventually quarrel.) At this point the “Gaius” and “Julius” disappeared, to be replaced by “Imperator”: a military title used by troops to acclaim successful leaders, and the root of the English word “emperor.”

Within another decade this “Imperator Caesar Divi Filius” had successfully wrested absolute control of the vast Roman dominions from his one remaining rival, Antony, whom he defeated at Actium in 31 BC and who committed suicide a year later, along with his paramour Cleopatra. (As the imperator gave the order to murder Cleopatra’s teenaged son Caesarion—a potential rival, since the youth’s father had been Julius Caesar himself—he remarked that “too many Caesars is no good thing.”) Master of the world at thirty-three, he then set about consolidating his power, craftily legitimating his autocratic rule under the forms of traditional republican law, and establishing the legal, political, and cultural foundations for an empire that would persist, in one form or another, for the next fifteen centuries.

One title that this astonishingly adept figure never used was rex, “king”—a word much loathed by the Romans, some of whom killed his great-uncle partly out of fear that he wanted to be one. The master of the world referred to himself as princeps, “first citizen.” In 27 BC, ostensibly in gratitude to the new Caesar for ending a century of civil bloodshed and establishing political stability at home and abroad, the Roman Senate voted him an additional honorific name that had suggestive religious associations: augustus, “the one to be revered.” The name by which he has come to be known bears no resemblance whatsoever to the one he was born with.

Advertisement

No resemblance to his former self: it is here that the hidden kinship between Augustus and its two predecessors lies. A strong theme in Williams’s work is the way that our sense of who we are can be irrevocably altered by circumstance and accident. In his Augustus novel, Williams took great pains to see past the glittering historical pageant and focus on the elusive man himself—one who, more than most, had to evolve new selves in order to prevail. The surprise of his final novel is that its famous protagonist turns out to be no different in the end from this author’s other disappointed heroes; which is to say, neither better nor worse than most of us. The concerns of this spectacular historical saga are intimate and deeply humane.

2.

The life of the first emperor is an ideal vehicle for a historical novel: Augustus is a figure about whom we know at once a great deal and very little, and hence invites both description and invention.

The biographies and gossip, recording and conjecturing began in the emperor’s own lifetime. One Life was written by a friend and contemporary of Augustus’s who appears as a character in Williams’s novel: the philosopher and historian Nicolaus of Damascus, erstwhile tutor to the children of Antony and Cleopatra. The emperor himself composed an official autobiography, the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (“Deeds Accomplished by the Divine Augustus”), clearly intended as a form of political propaganda. Inscribed on bronze tablets that were affixed to the portals of his mausoleum, it was reproduced in inscriptions throughout the Empire.

If we are to believe Tacitus, writing a century after Augustus’s reign, the obscurity of the emperor’s nature and aims was already a subject of discussion among his contemporaries. In his Annals, that historian paraphrases a debate that took place at the time of the emperor’s death, at the age of seventy-five, in 14 AD:

Some said “that he was forced into civil war by the duty owed to a father [Julius Caesar], and by the necessities imposed by the state, in which at the time the rule of law had no place…and that there was no other remedy for a country at war with itself than to be ruled by one man.”

And yet:

It was said, on the other hand, “that duty toward a father and the exigencies of state were merely put on as a mask: it was in fact from a lust for domination that he had stirred up the veterans by bribery…he wrested the consulate from a reluctant Senate and turned the arms that had been entrusted to him for a war with Antony against the republic itself. Citizens were proscribed and lands divided…Undoubtedly there was peace after all this, but it was a peace that dripped blood.”

The emperor may, indeed, have cultivated a certain opacity as a means of maintaining control: if his motives were hard to guess, so too would his actions be. Small wonder that his official seal was the enigmatic, riddling Sphinx.

How to write about such a figure? In Augustus, the question is slyly put in the mouth of the emperor’s real-life biographer Nicolaus. “Do you see what I mean,” the confounded scholar writes after a meeting with Augustus, whose notorious prudence he cannot reconcile with an equally notorious penchant for gambling. “There is so much that is not said. I almost believe that the form has not been devised that will let me say what I need to say.”

This is an in-joke on Williams’s part: the form Nicolaus dreams of—which is of course the one Williams ended up using—is the epistolary novel, a genre that wasn’t invented until fifteen centuries after Augustus. And yet its roots go right back to his reign. The Roman poet Ovid—also a character in Augustus, providing gossipy updates on the doings of the imperial court—composed a work called Heroides (“Heroines”), a sequence of verse epistles by mythical women to their lovers.

The epistolary form, so long associated with romantic subjects, is in fact ideally suited to Williams’s quasi-biographical project. (The form had been used with great success by Thornton Wilder in The Ides of March, his 1948 novel about Caesar’s assassination.) The portrait Augustus creates, refracted through not only (invented) letters but also journal entries, senatorial decrees, military orders, private notes, and unfinished histories, is at once satisfyingly complex and appropriately impressionistic, subjective. The authors of the invented epistles and documents are, with very few exceptions, real-life characters, and Williams, who expressed impatience with historical fiction that crudely “updated” the past, clearly relished the opportunity to impersonate some well-known figures.

Advertisement

Here, then, is the wit and also the preening of Cicero, the orator who, despite his opposition to Julius Caesar, was allied at one point with the young Octavian, whom at first he dangerously underestimates. (“The boy is nothing, and we need have no fear…I have been kind to him in the past, and I believe that he admires me…I am too much the idealist, I know—even my dearest friends do not deny that.”) Here too is the worldly Ovid, his report to his friend Propertius on a day at the races in the emperor’s box nicely filigreed with self-conscious poeticisms: “The sun was beginning to struggle up from the east through the forest of buildings that is Rome….”

Even those figures who left few traces of their writing style appear fully fleshed and, as far as the historical record permits us to know, true to life. Maecenas, the well-born patron of the arts and a friend to Horace, Vergil, and Augustus—who ridiculed his friend’s effete style—is presented as an aesthete (“much has been said about those eyes, more often than not in bad meter and worse prose”) with a hint of steel. Augustus’s ambitious third wife, Livia, mother of his eventual successor, Tiberius, comes across as coolly pragmatic and no more excessively conniving than most of the people around her: a far more persuasive character than the Grand Guignol poisoner of Robert Graves’s I, Claudius. “Our futures are more important than our selves,” Williams’s Livia matter-of-factly writes to her son, demanding that he divorce his beloved wife in order to enter into a dynastic match with Augustus’s daughter, Julia, whom he loathes.

And Williams uses invented excerpts from a now-lost memoir by Marcus Agrippa—Augustus’s great friend from youth, leader of his military victories, his eventual son-in-law, and the father to his heirs—to give the tersely prosaic, “official” version of events:

And after the triumvirate was formed and the Roman enemies of Julius Caesar and Caesar Augustus were put down, there yet remained in the West the forces of the pirate Sextus Pompeius, and in the East the exiled murderers of the divine Julius….

Williams knows how to deploy the persuasive stylistic tic: to Agrippa he gives the habit of beginning his sentences with “and.” A possible criticism of the earlier novels is that the author occasionally works so hard to make the writing “beautiful” that it sometimes works against believability; Will Andrews in Butcher’s Crossing often expresses himself in a high style at odds with his extreme youth. The ventriloquism imposed by Augustus’s epistolary form saves Williams from this vice. It is his most rigorous work.

One shrewd choice that he made in writing Augustus was the decision to withhold the emperor’s own voice until the end, where we get to hear it at last in a long (again fictional) letter to Nicolaus of Damascus, which constitutes the novel’s short final section. Not surprisingly, the emperor’s account of his past doesn’t square with many of the suppositions and speculations that have preceded it. For instance, it now emerges that what a friend had understood at the time to be the young Octavian’s cry of grief and confusion on hearing the news of Caesar’s assassination was—at least as the aged emperor would now have his friend believe—merely an expression of “nothing…coldness,” followed by a feeling of triumph: “I was suddenly elated…. I knew my destiny.”

As if to underscore the unbridgeable distance between what is perceived and what is true, between the official and unofficial, public and private narratives of our own lives, Williams intersperses this climactic fictional mini-autobiography with italicized excerpts of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti. Where does the truth of a life lie? After reading Nicolaus’s authorized biography (and reflecting on his own official autobiography), Williams’s Augustus wryly comments that “when I read those books and wrote my words, I read and wrote of a man who bore my name but a man whom I hardly know.”

To the historical novelist, that unknowability can be an advantage. Like the best works of historical fiction about the classical world—Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian, Wilder’s The Ides of March, Graves’s Claudius novels, Mary Renault’s evocation of fifth-century Athens in The Last of the Wine—Augustus suggests the past without presuming to recreate it.

3.

To have attempted simply to recreate the past would have left no room for the serious literary concern at the heart of Augustus and the author’s other works. In a 1985 interview, Williams described what he saw as the common theme of both Stoner and Augustus:

I was dealing with governance in both instances, and individual responsibilities, and enmities and friendship…. Except in scale, the machinations for power are about the same in a university as in the Roman Empire….

The effect of power (and of struggles for power) on individuals is, in fact, a theme of the episode in Augustus’s reign that first captured Williams’s imagination and would set the novel in motion. Not long after the publication of Butcher’s Crossing, he heard the story of the devastating scandal that had rocked both the empire and the imperial family: in 2 BC Augustus was forced to exile his beloved daughter and only child, Julia, to a tiny island called Pandateria. One of the charges was adultery—a violation of the strict morality laws her father had instituted as part of his campaign to renew old-fashioned Roman virtues in his new state. (By that point Julia, trapped in her hateful marriage to Tiberius, was notorious for her flagrant affairs.) Another was treason: there is a strong suggestion that some of the men whom she took as lovers were part of a faction opposed to Tiberius’s succession.

In this tale of a spirited woman whose passions brought her into disastrous conflict with her obligations, Williams perceived a compelling theme: what he called “the ambivalence between the public necessity and the private want or need.” This tension is one that his Julia, among the novel’s subtlest and most arresting characters—intelligent, ironic, rebellious, worldly, philosophical—tartly comments upon in the Pandateria journal Williams invents for her:

It is odd to wait in a powerless world, where nothing matters. In the world from which I came, all was power; and everything mattered. One even loved for power; and the end of love became not its own joy, but the myriad joys of power.

It is no accident that Augustus falls into two main sections: the first recounts his unlikely, triumphant rise to power, whereas the second, anchored by Julia’s journal entries, maps the disintegration of his family and personal happiness, largely as the result of his machinations to perpetuate his power through ill-conceived dynastic marriages. Which is to say, Part I is about success in the public, political sphere, and Part II about failure in the private, emotional sphere—the latter being a potential cost, Williams suggests, of the former.

The conflict between individuals and institutions is also at work in Stoner—the book that Williams wrote immediately after learning of the Julia story, the contours of which Stoner’s narrative to some extent inverts. For its thwarted hero repeatedly submerges his private wants to his larger obligations. There is an unhappy marriage alleviated too briefly by an affair with a sympathetic graduate student. (The novel’s one significant failure is the portrait of Stoner’s harridan of a wife: engineered to make Stoner miserable, she is far nastier than she needs to be.) There is fatherhood. Williams is particularly good on the tenderness of father–daughter relationships, both here and in Augustus.

And there is the middling career, delicately supported by a few cautious allies and open to threats from one or two academic enemies he has inevitably made in the course of things. One, who is bitter at Stoner’s criticism of a protégé, succeeds in thwarting Stoner’s progress and happiness over many years. In Augustus, a character called Salvidienus—a bosom friend of the emperor’s youth who ultimately betrayed him—observes in his “Notes for a Journal” that “every success uncovers difficulties that we have not foreseen, and every victory enlarges the magnitude of our possible defeat.” This is another of Williams’s major themes.

And yet Williams’s work cannot be reduced to a series of parables about individuals struggling with, and within, institutions. Among other things, such an approach can’t account for Butcher’s Crossing, a work in which the strictures of society and its institutions are almost wholly absent; it is, if anything, their absence that creates some of the dreadful outcomes in that novel, which charts the characters’ descent, during and after the buffalo hunt, into a precivilized, asocial stupor (“their food and their sleep came to be the only things that had much meaning for them”).

The main theme at play in all three of Williams’s mature novels is in fact rather larger: it’s the discovery that, as Stoner puts it to the mistress he must abandon for the sake of his family and his job, “we are of the world, after all.” All of Williams’s work is preoccupied by the way in which, whatever our characters or desires may be, the lives we end up with are the often unexpected products of the friction between us and the world itself—whether that world is nature or culture, the deceptively Edenic expanses of the Colorado Territory or the narrow halls of a state university, the carnage of a buffalo hunt or the proscriptions of the Roman Senate. At one point in Augustus a visitor to Rome asks Octavian’s boyhood tutor what the young leader is like, and the elderly Greek sage replies, “He will become what he will become, out of the force of his person and the accident of his fate.”

An inescapable and sober conclusion of all three novels is that the friction between “force of person” and “accident of fate” becomes, more often than not, erosion: a process that can blur the image we had of who we are, revealing in its place a stranger. Just before Will Andrews leaves for the buffalo hunt, a kindly whore he wants but cannot bring himself to sleep with—his loss of innocence will take another form, during and after the hunt—warns the soft-skinned and handsome young man that he’ll change and harden. This prophecy comes quite literally true at the height of the slaughter of the buffalo:

In the darkness Andrews ran his hand over his face; it was rough and strange to his touch;…he wondered if Francine would recognize him if she could see him now.

Similarly, Stoner understands at the end of his life that whatever his ideals may have been, they have yielded to chance and necessity, which have made him other than what he had hoped:

He had dreamed of a kind of integrity, of a kind of purity that was entire; he had found compromise and the assaulting diversion of triviality. He had conceived wisdom, and at the end of the long years he had found ignorance. And what else? he thought. What else?

So too Williams’s Augustus, whose many names reflect with particular vividness the processes of unexpected evolution and irreversible erosion so fascinating to this author. In Augustus’s concluding letter to Nicolaus, Stoner’s word “triviality” tellingly reappears, as the dying emperor ruefully becomes aware of “the triviality into which our lives have finally descended.” What occasions this thought is Augustus’s weary realization that the peace and stability for which he has struggled for so long and staked his career and reputation may not, after all, be what the Roman, or indeed any people, want: “The possibility has occurred to me that the proper condition of man, which is to say that condition in which he is most admirable, may not be that prosperity, peace, and harmony which I labored to give to Rome.” He has founded his empire, in other words, on a misconception.

This painful concluding irony is typical of Williams. It bears a strong resemblance, for instance, to the awful end of Butcher’s Crossing, when the buffalo hunters return at last to civilization after the slaughter only to find that, during the months of their absence, the bottom has dropped out of the market for buffalo hides—which means that all their labor, all the slaughter, the deprivations and sacrifices, have been in vain. In Augustus, the irony is painfully underscored in a brief coda that takes the form of the last of the many documents the author so imaginatively invents: a letter written forty years after the emperor’s death by the now elderly Greek physician who had attended him on his deathbed. In it the writer, having weathered the reigns of the cruel Tiberius and the mad Caligula, celebrates the advent of a new emperor who “will at last fulfill the dream of Octavius Caesar.” That emperor is Nero.

And yet Williams didn’t see his heroes as failures; nor should we. In the long interview he gave a few years before his death, he remarked that he thought Stoner was “a real hero”:

A lot of people who have read the novel think that Stoner had such a sad and bad life. I think he had a very good life…. He was doing what he wanted to do, he had some feeling for what he was doing, he had some sense of the importance of the job he was doing. He was a witness to values that are important…You’ve got to keep the faith.

“Keep the faith”: these characters may have grown away from the selves they thought they would be, but what they come to understand is that the lives they have made are “themselves”—the dwellings they must inhabit, and must find the courage to inhabit alone.

This knowledge is tragic, but not necessarily sad. At the end of the affair that threatens the modest life he has painstakingly, confusedly created, Stoner gently tells his lover, Katherine, that at least they haven’t compromised themselves: “We have come out of this, at least, with ourselves. We know that we are—what we are.” William Andrews returns from the buffalo hunt dimly aware that his dream of oneness with Nature was a glib fantasy, and that the lessons he took away from his encounter with the wild were different from the ones he imagined he’d be learning—the “fancy lies” a bitter, older partner contemptuously dismisses: “there’s nothing, nothing but yourself and what you could have done.” As with Greek tragedies, Williams’s novels expose the process by which “what you could have done” is gradually stripped away from a character, leaving only what he did do—which is to say, the residue that is “yourself.”

So too with the Imperator Caesar Divi Filius Augustus, who in the last pages of Williams’s final novel stoically embraces the truth that Andrews’s colleague sourly complained about. To confront one’s self, stripped of pretense and illusion, is the climax to which every life inevitably leads, however great or humble:

I have come to believe that in the life of every man, late or soon, there is a moment when he knows beyond whatever else he might understand, and whether he can articulate the knowledge or not, the terrifying fact that he is alone, and separate, and that he can be no other than the poor thing that is himself.

This is the conclusion to which many good biographies and some of the best works of fiction also lead. “The poor thing that is himself” is hardly the way that most of us would think about the first Roman emperor. It is the achievement of Williams’s novel that we are able to do so by its end, and to think of that end as a satisfying one.

-

*

This essay will appear, in different form, as the introduction to a new edition of Augustus, published by NYRB Classics on August 19, the two thousandth anniversary of the emperor’s death. ↩