Human rights organizations today have a major part in international affairs. My organization, Human Rights Watch, works in ninety countries, including virtually all those suffering war or severe governmental repression. Amnesty International, the largest rights group, has similar coverage and three million members around the world. These two big international human rights groups are joined by diverse and vigorous groups and activists working in virtually every country of the world other than the most closed and repressive. Together, they investigate a wide variety of human rights abuses by governments and armed groups, publicize their misconduct, and generate often intense pressure for change.

Just in the last year or so Human Rights Watch has had a significant influence in such matters as forcing Rwanda to stop supporting the abusive M23 rebel group in eastern Congo, leading to its demise. It had a leading part in convincing the French government and the United Nations Security Council to deploy peacekeepers to stop the mass slaughter in the Central African Republic. It contributed to China’s decision to abolish its system of administrative detention known as “reeducation through labor.” It showed that the Syrian military was responsible for the sarin attack in the suburbs of Damascus, adding to the pressure for Syria to relinquish its chemical weapons. It helped to secure a major new treaty among dozens of nations strengthening the existing prohibitions on forced labor. And much more.

But as the international human rights movement, and particularly the big global organizations, have gained prominence and influence, they have become the subject of growing academic interest, much of it critical. In the most recent example, The Endtimes of Human Rights, Stephen Hopgood argues that the accomplishments of the human rights movement are the product of a fading political moment. Hopgood laments the passing of the movement’s early days in the 1960s and 1970s when small groups of Amnesty members sat around kitchen tables and wrote letters on behalf of “prisoners of conscience” in such places as Communist Czechoslovakia and Pinochet’s Chile or lit candles in church basements in solidarity with them. Hopgood admires these early activists for standing “as spiritual guardians outside the prevailing global regime of politics and money.” They were, in his view, characterized by their “detachment from power politics,” acting with a purity that was “without self-interest.”

Today, however, Hopgood sees organizations run by human rights professionals who, he says, are “throwing in their lot” with the US government and other Western powers while losing touch with the movement’s popular origins. Beginning in the 1980s, he writes, human rights organizations have allied themselves much too closely in particular with the US government, whose support has been inconsistent and whose influence in any event is declining in an increasingly multipolar world. By entering “the profane worlds of state power and money,” he suggests, human rights groups have lost the moral authority of the sacred and become the “dispensable allies of power.”

He urges rights groups to return to their roots, grounded in a popular movement, untainted by the power politics of the state and the insider’s perspective of a professional staff—to move, as he puts it, from Human Rights to human rights. For Hopgood, the human rights movement should be more about people asserting the dictates of their conscience through the old Amnesty-style protest campaigns than professionals investigating human rights abuses and then shaming those responsible in the media and enlisting powerful governments in an effort to change their conduct.

Hopgood also chides human rights groups for helping to develop and now relying on “abstract human rights norms”—by which he means the international accords on human rights and humanitarian law. These he sees as detached from ordinary people. The legitimacy of such norms, he says, is increasingly questioned by people outside the West—people who are more likely to be guided by their religious beliefs than the secular values that supposedly informed the norms’ creation.

Hopgood attributes this alleged remove from popular values and the parallel focus on power politics to the movement’s shift from its European origins (Amnesty was founded in London) to the United States, and implicitly, from the early days of Amnesty’s grassroots activists to the current dominance of a strategy, which he associates with the younger, New York–based Human Rights Watch, of generating pressure on abusive governments through the media and sympathetic governments with influence.

There is an element of truth in Hopgood’s critique, but also much caricature. It is true that one of the great accomplishments of the human rights movement has been the codification of international standards in a series of multinational treaties: broad conventions such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, more focused ones on such matters as the rights of women, children, and people with disabilities, and prohibitions on certain indiscriminate weapons such as antipersonnel landmines and cluster munitions. These provide an opportunity for governments to commit themselves to respect rights and periodic reviews to assess their compliance.

Advertisement

In recent years, the treaties have been augmented by institutions such as the International Criminal Court and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, which can monitor and report violations of human rights and, in some cases, prosecute the people responsible. For example, the International Criminal Court has filed charges against the former president of Ivory Coast and the current presidents of Sudan and Kenya. Hopgood dismisses these developments as formalistic—a legal and institutional superstructure divorced from the populism that informed the movement’s simpler past and is the ultimate source of its strength.

But the current activities of the human rights movement do not, as he implies, rely on lawyers quietly and mechanistically comparing governmental behavior with rarified treaties that few have read. Rather, the movement is powerful because of its ability, often at great risk, to conduct detailed, on-the-ground investigations of human rights abuses and then to use the information gathered to shame and pressure governments that fall short of public expectations for their conduct. One of the most important assets of the human rights movement is its ability to focus public attention on the abuses that it investigates and documents. The work of Human Rights Watch is cited in the global media dozens of times a day.

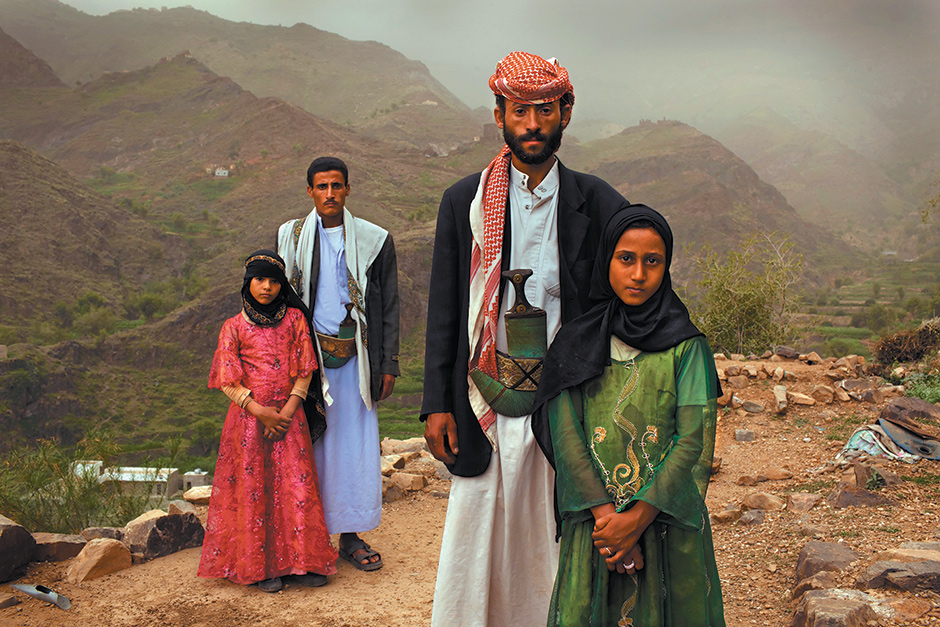

When human rights groups focus attention on abusive governments, whether in Burma, Egypt, Russia, Venezuela, or a host of others, it can subject them to opprobrium among their public and governmental peers that officials often go to great lengths to avoid. When the pressure works, it is because leaders realize that they can end the bad press only by stopping their bad conduct. Yemen, for example, recently introduced a bill setting eighteen as the minimum age for marriage after a Human Rights Watch report criticized child marriage in the country. Burma, under criticism from rights groups, has delayed plans to introduce discriminatory anti-Muslim legislation.

The working standard for such criticism is not international law per se but popular judgment. The law is relevant for shaping public opinion—particularly in matters such as the conduct of war, or even the use of torture, where the public may not intuitively understand what constraints human rights norms impose on government conduct. But in the absence of international courts to uphold most treaty commitments, exposing a violation of human rights law will generate pressure to end it only if the public disapproves of the conduct. Hopgood decries the human rights movement for not doing more to solicit direct action by members of the public, but the movement’s primary methods of investigation and exposure are intimately linked to public opinion. If publicizing a rights violation does not lead to condemnation in the media and by concerned members of the public, the written law will make little difference.

The same dynamic lies behind the human rights movement’s enlisting of powerful governments. Appeals to the dictates of international law are far less important in moving such governments to use their influence to defend rights than are reports in the media informing people of serious abuses. The public, in turn, often demands that its government avoid complicity in abuses by repressive regimes and use its clout to curb them. The US and other governments, for their part, can make abusive leaders pay a price for that abuse, whether in lost military aid, targeted sanctions, or diplomatic snubbing. That price can make a leader decide to stop committing human rights violations.

For example, on the eve of Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’s recent trip to a Washington summit where he anticipated that the country’s anti-homosexuality law would face official criticism, a Ugandan court suddenly ruled it unconstitutional. The Burmese military has allowed a degree of democratization to escape the crippling sanctions imposed by Western governments in response to its repressive rule.

These are powerful tools. Yet Hopgood belittles them as “elite mobilization,” in contrast with the popular mobilization that he prefers. But behind the verbiage seems to be a dislike for the means used to influence public opinion. It is true that groups like Human Rights Watch tend to focus on better-informed media, because they are more likely to have the sophistication needed to address these often complex issues. To dismiss this use of media as “elite” is to neglect its enormous impact in shaping public opinion throughout society. Moreover, because of that influence, and in the absence of day-to-day polling, policymakers often look to such media as a surrogate for the public’s views, compounding their influence.

Advertisement

Groups like Human Rights Watch also use a variety of means to mobilize the public directly, from its more than two million followers on Twitter and Facebook to its widely visited website and YouTube channel. Hopgood seems to prefer the more personal appeals used in the early Amnesty days, but those methods, such as organized letter-writing campaigns, are extraordinarily time-consuming, expensive, and, by contrast with modern electronic methods, inefficient. Amnesty itself has largely moved on from them.

Hopgood acknowledges that the public must sympathize with human rights values for them to have an effect, but for him, especially once he looks outside the West, that reliance on public support is more a threat than an opportunity. His assessment reflects his view that rights are conceived in and imposed by the West rather than aspirations for humanity shared by people around the world.

But this is simply not true: a farmer in China will be just as angry as one in Nebraska if, say, his land is expropriated at gunpoint; each will want a legal and political system to redress this wrong. Malala Yousafzai—the now-seventeen-year-old Pakistani advocate for girls’ education—was hardly a Western creation. Nor were the Arab youths or Ukrainian protesters who were seeking democracy, the Chinese dissidents asserting their right to basic freedoms, the Latin Americans standing up to military dictatorships, or Nelson Mandela’s anti-apartheid movement.

Hopgood points to rising religiosity outside the West as indicative of a growing number of people who reject human rights standards. He is only partly right. The major religious traditions—as well as most people the world over—agree on the importance of many human rights standards: from prohibitions of summary executions, torture, and arbitrary detention to the duty to devote available resources to improve access to health care and education.

Some religious traditions certainly do have narrow or harsh views, or both, on such matters as gender equality, religious freedom, and the rights of gays and lesbians, but the matter is complicated. The increasingly integrated world of modern communications and travel offers promise that understandings of religious traditions will change, even as the change itself sometimes sets off reaction. For example, despite the Catholic Church’s opposition to homosexuality, it now also opposes violence and discrimination against gays and lesbians as well as the criminalizing of homosexual conduct.

Sharia, or Islamic law, is often cited as a great threat to women’s rights, but that depends to a large degree on who is doing the interpreting. ISIS and its ilk are without question a threat, but an imam in Iraqi Kurdistan recently issued a fatwa against female genital mutilation, to great effect. Predominantly Muslim countries like Tunisia, Yemen, Lebanon, and Egypt have in recent years taken positive steps on women’s rights. Even Saudi Arabia, whose Wahabi interpretation of Islam is among the most conservative, has been gradually expanding the range of activities permitted women in public life—from education to participation in professions like the law—though with major restraints such as the continuing ban on women’s travel without the permission of a male guardian.

Meanwhile, such recent setbacks as the criminalizing of promotion of homosexuality in Nigeria, Russia, and, until it was overturned, Uganda have less to do with religion and more to do with the efforts of embattled presidents to shore up their political position by pandering to conservative forces. It is also a reaction to the increasing confidence of gays in these countries who had been living more openly and advocating for their rights. In short, the relationship between religion and rights is more nuanced and dynamic than the dark future that Hopgood foresees.

Moreover, in his suggestion that the human rights movement is imposing itself on non-Western cultures, Hopgood concentrates on the major international groups like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International while devoting little attention to the vast global movement of popular human rights organizations. These activists, in such countries as Egypt, Colombia, India, Russia, and China, represent popular assertions of the importance of defending rights, some covering the full panoply of rights, others the rights of certain subsets of people such as women, people deprived of their land, or communities facing environmental devastation. Such activists’ groups are smaller than the global giants, and more vulnerable to violence and retaliation by local powers unhappy with being held to account, yet they represent anything but the detached, declining, Western-dominated movement that Hopgood sees. Their increasing effectiveness greatly strengthens the entire human rights movement, ensuring that local priorities and voices have an important part in setting agendas for investigation and advocacy.

In part to build closer partnerships with these local activists—from combating their persecution to projecting their concerns onto the global stage—the international groups are increasingly basing their staff around the world. This fosters more intimate connections than were allowed by the “parachute” visits of the human rights movement’s earlier days. Indeed, the international groups are increasingly composed of these activists, not just Westerners. The Human Rights Watch staff of 415 includes seventy-six nationalities, based in forty-seven countries. Amnesty International’s core staff of 530 includes sixty-eight nationalities and is based in thirteen countries.

Hopgood neglects the rise of such non-Western rights activists. Instead, he sees a threat in the increasing power of non-Western governments such as Brazil, India, and South Africa—governments that lack a tradition of promoting human rights in their foreign policies. Western governments still retain significant influence, although their moral authority has been compromised by transgressions such as the US government’s Guantánamo detentions, CIA torture, unlawful drone attacks, and mass electronic surveillance. But there is no question that their relative power is waning.

Yet this is a transition to which the human rights movement is already reacting. Human Rights Watch, for example, traditionally focused on enlisting the influence of the major Western powers, with advocacy offices in Washington, Brussels, London, Paris, and Berlin. However, in recent years, the organization has also expanded the reach of its advocacy outside the West to such countries as Brazil, India, Japan, and South Africa. By building relationships with officials in these governments who are sympathetic to human rights, and encouraging journalists and activists in those countries to pay attention to their government’s conduct abroad, Human Rights Watch is working to bring their foreign policies more in line with the values informing their democratic domestic systems. Amnesty International is making a similar effort to expand its membership outside the West, reporting members in more than 150 countries.

These combined efforts are in an early stage, but they are hardly a pipe dream. Japan, for example, recently took the lead on a human rights initiative for the first time—sponsoring the establishment of a highly successful UN commission of inquiry into rights abuses by North Korea. India twice provided critical votes in support of UN efforts to press for investigation of large-scale war crimes in neighboring Sri Lanka. Brazil is at the forefront of efforts to establish global standards to rein in mass electronic surveillance. South Africa led an important UN effort to defend the rights of gays and lesbians.

These advances are accompanied by plenty of setbacks. Many of these non-Western powers are still dominated by foreign ministries that see advocacy of human rights as an infringement of state sovereignty. The process of convincing these governments to be more respectful of human rights in their foreign relations is a long-term project. But Hopgood, referring to the Treaty of Westphalia that established the system of national sovereignties in 1648, exaggerates when he says we are entering a “neo-Westphalian world” of “renewed sovereignty…and the stagnation or rollback of universal norms about human rights”—or “Eastphalia,” as he names it.

Moreover, Hopgood’s reminiscences about the halcyon days of the human rights movement are themselves only partial. As Barbara Keys describes in her new book, Reclaiming American Virtue, in Amnesty’s early days in the United States there was already tension between the purists around the kitchen table and a professional staff that even then used mass-market fundraising to build a lobbying capacity in Washington. Hopgood reflects a contemporary version of that tension when he dismisses the engagement of mass-market donors as “slacktivism”—a “shallow but wide commitment” without “deeper social roots”—rather than the more profound commitment that he recalls from earlier times.

But there was an inherent conservatism even in the early days of Amnesty. As Keys describes it, Amnesty tended to present the victims on whose behalf its citizen groups worked as voiceless and detached from governmental policies. It would seek an end to the torture of a prisoner or the release of a prisoner of conscience, but not a transformation of the policies and practices responsible for these wrongs. In that era, Keys explains, Amnesty treated

prisoners of conscience [as] fundamentally the same everywhere….The details were beside the point.The political causes prisoners waged and the political and social contexts in which they lived were elided as irrelevant.

Amnesty saw its mission, Keys writes, quoting one of their publications, as “to help people and not to reform governments.”

The human rights movement has long since transcended what Keys terms this “decontextualized approach” in which prisoners were treated “generically.” Human rights groups long ago learned the importance of addressing the policies that yield human rights violations, rather than only the violations themselves. The broader transformative efforts in which both Amnesty and Human Rights Watch now engage is, in my view, to be celebrated, not denigrated, as Hopgood does, as the sullied world of politics.

Still, Amnesty has always been more uncertain about its relationship to powerful governments than Human Rights Watch is. In its early days in the United States, Keys explains, Amnesty felt more comfortable lobbying the more populist Congress than the more professional State Department, and it tended to limit itself to expressions of concern about political prisoners rather than advocating the economic sanctions that Human Rights Watch sometimes sought, such as the cutting of US military aid to abusive US allies in Central America in the 1980s.

But there has long been recognition throughout the human rights movement that, important as popular mobilization is, it must be supplemented by pressure through the media and influential governments. Hopgood says, “One could be a fast, globally active advocacy operation or a mass movement: it was becoming harder to be both.” That is only partly true. Amnesty’s current secretary- general, Salil Shetty, is placing great emphasis on building his organization’s membership in the global South, but over the last several months he has also joined me to meet with, among others, German Chancellor Angela Merkel about Russia, Ukraine, China, and electronic surveillance, and Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif about humanitarian access to Syria.

In fact, a movement consisting solely of part-time volunteers would be incapable of undertaking the complex field investigations in the midst of war zones and repression that are the foundation of most modern human rights work. Nor would a movement composed solely of amateurs have the proven expertise to attract the attention of journalists and policymakers, let alone the global presence to build close working relationships with local activists. It hardly strikes me as moral or wise to abandon proven methods of protecting the rights and lives of people around the world just because these methods require the raising of large amounts of money and engagement with the complex and sometimes compromised world of modern politics. Would people’s rights really be better protected if there were no Human Rights Watch or modern Amnesty International?

Of course the aims of the human rights organizations define the limits of what they can do. For example, human rights law protects the participants in political debates about such matters as climate change or public health but it cannot resolve whether we should adopt a carbon tax or a single-payer system of health insurance. Similarly, international humanitarian law, or the laws of war, address the ways that warring parties fight but not whether they should go to war or the terms for ceasing fire. Still, even within this necessarily limited sphere, human rights organizations can provide a powerful defense of the basic rights that enable people to live securely and with dignity. It can often serve as a trustworthy witness to violent acts that are in dispute and should be stopped. That is not to be dismissed lightly.

Hopgood condemns the professional staff that run modern human rights groups as elitist; I see it as a powerful antidote to the reluctance of governments to respect and defend rights. A professional staff is the vehicle by which concerned people pool their resources to deploy the power of information to keep governmental transgressions in check. It is not a threat to the human rights ideal but one of the essential ways to defend it.

This Issue

October 23, 2014

How Bad Are the Colleges?

Find Your Beach

Law Without History?