1.

“We are living under the reign of government gone amuck,” the keynote speaker proclaimed:

At every station in this society…government is feared and distrusted…. It is the Democrat Party…which has built the federal bureaucracy ever larger and larger and directed the agents of that bureaucracy to penetrate ever deeper and deeper into the conduct of all of this nation’s private affairs and personal lives. Yes it is the Democrat Party…which has unleashed upon the American people the curse and abomination of government which today careens about, so clearly out of effective control.

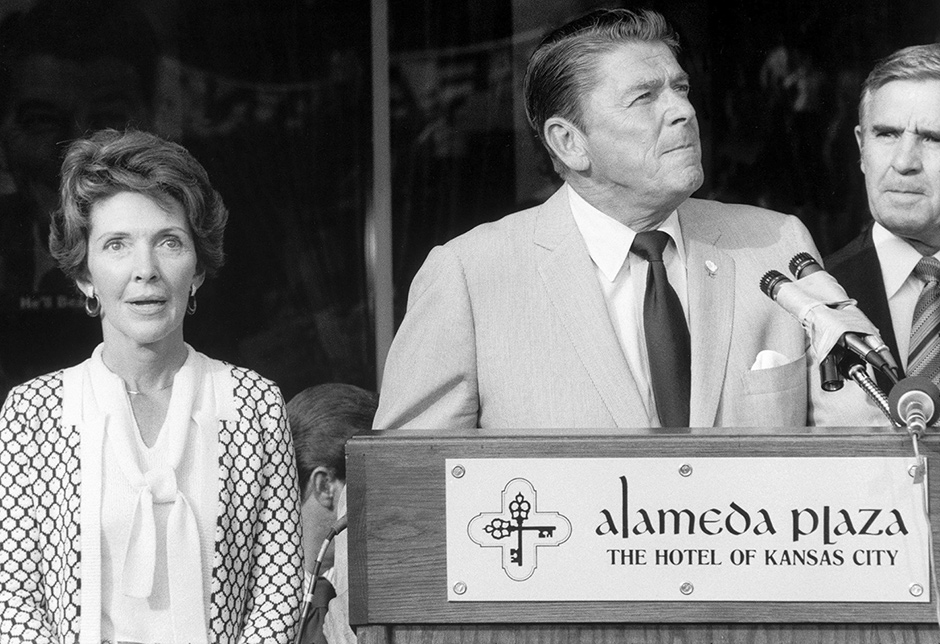

From a recent Tea Party convention, you might think; but you would be wrong by nearly four decades. This was the keynote address at the Republican National Convention in Kansas City in August 1976, a fascinating moment in modern American history. The keynote speaker was John Connally of Texas, a prominent Democrat himself for forty years before converting, three years earlier, to the Grand Old Party. He was a man of boundless ambition and limited scruple who had sensed that the political winds within the Republican Party were blowing rightward.

Five years earlier, as Richard Nixon’s treasury secretary, Connally orchestrated a presidential decree freezing wages and prices throughout the American economy—an intervention by government that didn’t involve a single Democrat except Connally. His speech, about the “curse and abomination” of government, was preposterous; but it reflected the conventional Republican wisdom that summer: the rhetoric of Ronald Reagan, the former Democrat and insurgent candidate for their 1976 presidential nomination, was more closely attuned to rank-and-file Republican sentiment than the uncertain bromides of the accidental president of the day, Gerald Ford.

Reagan nearly beat Ford for the nomination that year. If fifty-nine of the 2,257 convention delegates had switched from Ford to Reagan, Jimmy Carter would have faced the Hollywood actor four years sooner than he did. A Ford defeat would have been an unprecedented humiliation for an incumbent president, albeit one who came to the job by the strangest path ever followed to 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Reagan had sensed what activist Republicans most wanted to hear, and he appealed to their antipathy to government.

Today we have dreadful politics that feature unrestrained partisan warfare, a gridlocked government, and unprecedented public cynicism about politics and politicians. One of our two parties is dominated by a faction eager to undermine the functioning of the government. This grim situation may seem to have arisen since Barack Obama became president in 2009, but it has much deeper roots in the events of the 1960s and 1970s. John Connally’s 1976 keynote address is a powerful clue to this history.

2.

The books by John Dean and Rick Perlstein, different in approach and style, help explain the origins of today’s mess. Read together, they do much to bring the 1970s to life. For younger people (Perlstein himself was born in 1969), they may clarify large events that have already faded from political memory.

Perlstein has the grander ambition. He wants to convince us that Nixon’s humiliation in the Watergate scandal and Reagan’s unlikely challenge to Ford in 1976 are pieces of the same story of America coming unhinged. The Invisible Bridge is his third book about the rise of the new conservatism in America. The first, Before the Storm, considered the Barry Goldwater campaign of 1964; the second, called Nixonland, was devoted to Nixon’s rise and fall. A fourth will be an account of Reagan’s ultimate triumph in 1980. Presumably that book will argue that Reagan’s election was the culminating response to the unhinging of American society that Perlstein writes about here.

Essentially, The Invisible Bridge is an outsized example of what journalists call a “clip job”—an account based on the work of others. This is Perlstein’s “take” on the era, based on the work of scores of journalists, historians, and memoirists, whom he credits generously. He apparently interviewed few living participants in the events he describes, and none of the principals. Nor did he discover documents not previously found by earlier writers. He spent a lot of time watching movies and television shows from the Seventies, which enrich his narrative. He writes in hyped-up prose that can be convincing and amusing but is often exasperating.

Dean has a narrower focus and a more rigorous approach. The Nixon Defense is his third book on Watergate, and his most ambitious. For forty years he has been trying to deal with his complicated relationship with Nixon. In 1974 he spent four months in prison after pleading guilty to “obstruction of justice”: and he has since spent much of his time and energy trying to explain to himself and others just why that happened.

He took upon himself (with help from several assistants) the task of transcribing more than one thousand taped conversations from the Nixon White House that touched on Watergate. The four years Dean spent on this task produced a great deal of new information. “The tapes” are more informative than we had realized. Previously, prosecutors had transcribed only those they needed for the trials of various members of Nixon’s staff and workers in his reelection campaign. Nixon escaped a trial after Ford formally pardoned him, so even some tapes damning to the president had never been transcribed until now.

Advertisement

Dean used these newly transcribed conversations and the many books written by Watergate figures to reconstruct a kind of Watergate diary, recording almost day-by-day Nixon’s efforts to deal with the crisis. The book makes clear that Nixon had no defense, and was guilty of high crimes and misdemeanors beyond any doubt. The defense he mounted was an elaborate mountain of lies. “Fortunately for everyone,” Dean writes, “his defense failed.”

3.

The event that did the most to shape the era Perlstein and Dean write about was the Vietnam War. Nothing that happened since World War II approaches its historical significance. Without Vietnam, Nixon’s 1960 presidential campaign surely would have been his last. Without Vietnam, the collapse of public confidence in government and politics that invigorated the “New Right” of the 1970s and made Reagan a contender could not have occurred as it did.

Beyond the obvious—58,300 dead Americans, perhaps a million dead Vietnamese, hundreds of billions of dollars squandered—the costs of our Vietnam mistake were staggering. They included the country’s loss of faith in government; the end of a culture of shared sacrifice born in World War II, embodied in the army of drafted citizens that Vietnam ended; and the postwar economic boom, abruptly terminated in 1973. (The incomes of working families have languished for four decades since.)

The war shattered and discredited the ruling elite that had emerged from World War II ready to “pay any price, bear any burden…to assure the survival and the success of liberty,” in the words of John F. Kennedy. The war and the desegregation of the South crippled the Democratic Party, which had dominated US politics since 1932 until two Democratic presidents led us into Vietnam. The war split the party and ruined Democrats’ self-confidence. As more than a million young men were conscripted to serve during the Johnson administration, opposition to the war and the draft was at the core of many of the radical movements and protests that divided Democrats so bitterly. The Democratic Party has never rediscovered its voice as the progressive defender of working people.

Watergate was the second momentous development of this era. Largely because of the Vietnam disaster, Americans elected Nixon to put the country on a different course. He established relations with China, found a modus vivendi with the Soviet Union, and abolished the draft in 1973, large and popular accomplishments. But he also sank deeper into the Vietnam mire and presided over bad economic conditions, including a fierce inflation that terrified many Americans. And then, after his reelection by a landslide, the public found that a neurotic, deeply insecure man had taken over the White House. His abuses of the presidency had no known precedent. Their exposure traumatized the nation.

Vietnam plus Watergate: a formidable combination that left many Americans without faith in their governors. Together they produced a new version of the United States—a country that had for the first time lost a war and put a criminal in the White House.

But the country was not helpless, as the response to Watergate showed. From the news media to Congress and most of the nation’s politicians, Americans rose to the occasion. First The Washington Post, then many other outlets pursued the Watergate story relentlessly and made it impossible for public officials to shrug it off. A Republican in Nixon’s cabinet, Attorney General Elliot Richardson, supported the FBI and Justice Department investigations of Watergate. Senators Sam Ervin of North Carolina and Howard Baker of Tennessee, the ranking Democrat and Republican on the Senate’s special Watergate Committee, oversaw a thorough congressional investigation that sank the Nixon presidency. Both Democrats and Republicans on the House Judiciary Committee voted to impeach Nixon. Finally, senior Republican senators led by Barry Goldwater of Arizona told Nixon he had to go. For the first time in US history, a sitting president resigned.

That these forces could mobilize effectively in such lawless times demonstrated that the American experiment had not failed yet. There were other hopeful signs. Women were mobilizing to promote their rights, and Congress approved in 1972 the Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution. Black Americans became more visible. For the first time since Reconstruction a black man, Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, was elected to the Senate; white Americans fell for a successful black family on television (The Jeffersons); young blacks enrolled in unprecedented numbers at Yale and Harvard. After the Stonewall riot in 1969, gay people began to make open demands to be treated equally.

Advertisement

4.

Perhaps the hardest part of writing the history of a specific period is coping with the complex, contradictory events that confuse those who live through it.

Rick Perlstein writes history with an ideological purpose, to show the relentless rise of conservatism. He does not adequately consider contradictory evidence of the kind I’ve mentioned. He does not acknowledge the ambiguity of those times, when awful and hopeful coexisted. He argues that the country lost an opportunity to really learn from the disasters of the Sixties and Seventies. He thinks we should have faced up to the fiasco of Vietnam, to the excesses of Nixon, to the sins of our secret agents who tried to assassinate foreign leaders—to the fact that we were sinners, not heroes or chosen ones, who had allowed our country to stray from its ideals.

We should, in Perlstein’s view, have pursued a new patriotism based on brutal honesty and confession of those sins. Many Americans were ready to embrace this approach—“the suspicious circles,” he calls them, one of the “two tribes of Americans” into which he divides the populace. But according to him, the suspicious ones were bested by the other tribe, Americans whose credo was “never break faith with God’s chosen nation, especially in time of war—truth be damned.”

In Perlstein’s America, Ronald Reagan became the chief of that second tribe, a leading apologist for Vietnam and Watergate who never criticized Richard Nixon, who saw only good in America, that “shining city on a hill.” Perlstein suggests that Reagan ultimately succeeded by offering a myopic, even fraudulent view of America and its traumas in the Sixties and Seventies that reassured an agitated citizenry.

“Before Reagan had served a single day in any political office, a polarity of opinion was set—and it endured forevermore,” Perlstein writes. “On one side: those who saw him as the rescuer, hero, redeemer…. On the other side: those who found Reagan a phony, a fraud, or a toady.”

These stark distinctions are misleading. Perlstein forces Americans of the 1970s into rigid categories that few would have recognized. There weren’t two tribes, one ready to confess sin and the other determined to deny it. Instead there were millions of confused Americans who harbored the usual hodge-podge of opinions and emotions—if they bothered, as many did not, to reflect on the world around them. Similarly, Perlstein’s “polarity of opinion” about Ronald Reagan never existed in the extreme version he presents. Most Americans probably had no view of Ronald Reagan whatever before he served a single day in public office. Many serious people who observed Reagan during his entire career never took either of those absolutist positions.

Perlstein’s apocalyptic portrait of the late Sixties and early Seventies is another example of his insistence on polarity. Everything he mentions really happened: there were urban riots, bombs planted by anarchists and nihilists, two attempts to assassinate Gerald Ford, meat shortages and long lines at gas stations, and much more. But America was not falling apart, and—a hard lesson for many who write about politics to learn—most citizens, as always, paid scant attention to politics. There were pennant races to enjoy every summer, and football every autumn weekend, new Motown songs on the radio, and an emotional celebration of the Bicentennial in July 1976 (an event that Perlstein describes but is unable to absorb).

He seems to have read everything about the 1970s—and seen the patterns of good and evil he describes here. But he creates an impression of a country on the precipice of chaos that readers who lived through the period are unlikely to recognize as an accurate portrait. Like all polemicists, Perlstein simplifies to make his case; but it is a case that is too simple to be historically accurate.

5.

One political event that did capture the public imagination was the Watergate scandal. Huge audiences watched the hearings on television; people everywhere talked and argued about them. As the story unfolded, Americans got a civics lesson of a kind that had gone out of fashion in the nation’s classrooms: an introduction to congressional investigations and white-collar prosecutions, and to impeachment law.

John Dean’s vivid recreation of the White House response to Watergate is full of revelations about one of the strangest men ever to occupy the White House.* For those who closely followed Nixon’s fall, his book has some surprises.

Nixon was a sloppy decision-maker and manager. He ordered his chief of staff, Bob Haldeman, to destroy the White House tapes—twice; but Haldeman didn’t do it, and Nixon never tried to make sure his orders were carried out. Had he done so, Dean observes, he would have survived Watergate as president.

Nixon never watched television news and rarely read the newspapers, even Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s stories in The Washington Post. He relied on summaries provided by aides and acquaintances. For months after the Watergate break-in (which, Dean shows, he knew nothing about in advance), Nixon never tried to find out what had happened, who ordered it, or what the bugs implanted by Republicans in the Democratic National Committee offices had revealed. He seemed not to care.

From the early days of the drama in 1972, the Nixon administration knew that one of the Post’s important sources was Mark Felt of the FBI. A lawyer representing another news organization told the Justice Department that Felt was leaking like a sieve. Nixon and his colleagues felt they couldn’t fire the man who years later became famous as Deep Throat, Woodward’s long-secret source; they feared he would write a book about all that he knew.

For technical reasons, the famous eighteen-and-a-half minute erasure on one White House tape could not have been accomplished by Nixon’s secretary, Rose Mary Woods, and was probably the work of Nixon, his lawyers, or senior aides. But Dean argues persuasively that that gap was “ultimately meaningless.” Whatever was erased was matched on other tapes.

Nixon repeatedly confessed his crimes in recorded conversations. “I am just telling you,” he said to Al Haig, who succeeded Haldeman as chief of staff after Haldeman and his sidekick John Ehrlichman had to leave the White House, “that from a practical standpoint, if Bob Haldeman and John Ehrlichman and Chuck Colson’s memoranda of conversations with the president about any relation to Watergate are spread to the public record, it will destroy us.”

He also told Haig that “I ordered that they use any means necessary, including illegal means, to accomplish this goal. The president of the United States can never admit that.” He was talking about the “Huston Plan” that authorized extensive bugging of political enemies—along with break-ins to their offices—that Nixon approved long before Watergate.

“Watergate, as the overwhelming evidence revealed, was merely one particularly egregious expression of Nixon’s often ruthless abuses of power,” Dean writes. Thanks to the tapes, that will stand as history’s judgment.

6.

“One of the things Richard Nixon had been most expert at as president,” Perlstein writes, “was damping the ideological passions of his party’s right wing. Now, with Nixon gone, those passions thrummed.” Gerald Ford encouraged a sudden resurrection of the far right when he chose Nelson Rockefeller as his vice-president. Nixon had picked a nonentity, Governor Spiro Agnew of Maryland, as his running mate. His choice avoided alienating either of the principal factions of the 1968 Republican Party: the moderate-to-progressive wing centered in the Northeast and Midwest, and the “New Right” inspired by Barry Goldwater in 1964. (Agnew belonged to a third faction—bag men. This became clear when he had to resign in 1973 in the face of charges of corruption, which led to Gerald Ford becoming the thirty-eighth president.)

Rockefeller, the classic liberal Republican, combined political and cultural traits that were bound to inflame right-wing Republicans. He was seen as an arrogant billionaire liberal (although he had sponsored draconian drug laws as governor of New York). When he challenged the right-wing conservative politics of Barry Goldwater in 1964, he aggravated class resentments. Jesse Helms of North Carolina, a new kind of aggressive southern conservative, testified against Rockefeller’s confirmation as vice-president before the Senate Rules Committee. Rockefeller, said Helms, represented “a dynasty of wealth and power unequaled in the history of the United States” who could never put “the survival of the national interest” ahead of “the survival of ingrained dynastic values.” Four conservative senators, including Helms and Goldwater, voted against Rockefeller’s confirmation.

Ford’s selection of Rockefeller unleashed right-wing Republicans whom Nixon had restrained, and gave the country the New Right of the 1970s. These were direct descendants of the John Birch Society, which was still in business at the time, as well as Senator Joseph McCarthy and the fiercely right-wing magazine Human Events. All were obsessed with the threat of communism inside the US itself, and all were promoters of conspiracy theories. Richard Hofstadter had described this strand of America’s political life in his 1964 essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Hofstadter wrote of the sense of dispossession that motivated many on the far right in the 1960s:

America has been largely taken away from them and their kind, though they are determined to try to repossess it…. The old American virtues have already been eaten away by cosmopolitans and intellectuals; the old competitive capitalism has been gradually undermined by socialistic and communistic schemers; the old national security and independence have been destroyed by treasonous plots [involving] major statesmen who are at the very centers of American power.

Hofstadter was writing about people who became avid Goldwater supporters in 1964. Ford’s choice of Rockefeller as his vice-presidential candidate made it easy to mobilize them again on behalf of the former governor of California. Ronald Reagan was an enthusiastic subscriber to Human Events. He had made his first impression on the national Republican Party with a televised speech promoting Goldwater in October 1964, when he was still just a pitchman for General Electric. “The issue of this election,” Reagan said then, was “whether we believe in our capacity for self-government or whether we abandon the American revolution and confess that a little intellectual elite in a far-distant capitol can plan our lives for us better than we can plan them ourselves.” This speech made Reagan a hero on the right, a status he retained despite eight years governing California (1967–1975) as a flexible politician ready to make deals with his Democratic legislature.

Perlstein describes how Reagan backers, using mainly lists of New Right people that traditional Republican politicians overlooked, built support for him in 1976. The party establishment was startled by Reagan’s successes in early primaries and caucuses. Ford responded by mimicking Reagan and moving to the right, but the true believers were not persuaded. Perlstein quotes a memo from a Ford aide: “We are in real danger of being out-organized by a small number of highly motivated right wing nuts.” Patrick Buchanan, by then a columnist, crowed: “The liberal wing of the Republican Party is a spectator now…. The civil war in the GOP is between conservatives—militant and moderate.”

It would take another quarter-century to complete the decimation of old-fashioned moderate Republicans, but Buchanan was essentially correct in 1976. Though he lost to Ford, Reagan’s success in 1976 confirmed the rise of the New Right faction within the Republican Party.

Republicans had a long, bitter history of factional conflict. In 1912 factions aligned respectively with Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft split what was then the country’s majority party, so that Woodrow Wilson won the presidency. In the Forties and Fifties the GOP was divided between conservative midwestern isolationists led by Senator Robert Taft of Ohio and more pragmatic internationalists associated with Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York and, later, General Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 1964 Goldwater and Rockefeller supporters created a new version of Republican factional war. Dewey (the Republican candidate for president in 1944 and 1948), Eisenhower, and Nixon had all avoided challenging the New Deal and its progeny, but Goldwater cheerfully took them on—even Social Security. Goldwater was a disastrous national candidate, but triumphed within the GOP. His failed 1964 campaign gave rise to the antigovernment New Right that we live with today.

John Connally understood what was happening when he wrote his keynote address for the 1976 convention. He was himself part of the most important new faction in the GOP, created by the mass conversion of southern Democrats to the Republican Party. Lyndon Johnson had predicted this development on the day in 1964 that he signed the Civil Rights Act, and Goldwater had capitalized on it in the 1964 election, when he won only his state of Arizona and five deep South states that had never before voted for a Republican presidential candidate. Connally’s attack on government and Democrats in Kansas City was meant to appeal to this newest conservative faction in his new party.

In 1976 Goldwater supported Ford against Reagan. But writing to Ford that spring, he cautioned, “You are not going to get the Reagan vote. These are the same people who got me the nomination and they will never swerve.” At the convention in Kansas City, after Reagan supporters had yelled “sell-out” at him in the hall, Goldwater told a reporter that former supporters of his from 1964 who had gone to work for Reagan in 1976 included “some of the most vicious people I have ever known.”

7.

The anxious dispossessed whom Hofstadter discussed half a century ago can now be found in the ranks of the Tea Party, today’s far-right faction. They don’t run the Republican Party, as demonstrated by the many primary elections their chosen candidates have lost during this election year. But even as they lose electoral contests to “establishment” Republicans, they prevail ideologically. Their hostility to government and to President Obama trumps all other considerations.

The Tea Party is defined by what it opposes and dislikes. Polling of Tea Party supporters makes clear their hostility to the black man in the White House and to his nonwhite supporters, including newer Americans who look nothing like them. Alan Abramowitz of Emory University argues persuasively that the Tea Party is a product of growing racial and ideological polarization within the electorate.

Tea Party adherents and sympathizers in the House of Representatives have made it impossible for John Boehner, the Speaker, to muster a majority of his caucus to vote for any bill that suggests support for an active government in domestic affairs. The anti-government faction is in charge.

How long will that dominance last? We don’t yet know. Last October the House held a vote on a bill to increase the total amount of the national debt. Congress had earlier voted for the spending and taxes that forced this borrowing. By the time the debt ceiling needs to be raised, the money has been spent. Raising the ceiling has been a pro forma matter for years. Failing to do so would effectively force the United States to default on its obligations to creditors.

When the House voted last year, 144 of its Republican members said no—they voted to put their country into bankruptcy. Just eighty-seven Republicans voted yes, to allow the government to meet its obligations. Perhaps this was just symbolic—those 144 knew that Democrats (198 of them, as it turned out) would all vote yes, so the debt ceiling was raised with votes to spare. Yet some of the Republicans sounded as though they would welcome default, and more expressed confidence that default wouldn’t really matter. Symbolic or not, that 144 members of the House were willing to cast a vote to default on the full faith and credit of the United States is a sign of our times.

Those 144 House Republicans acted on an impulse that was first legitimized in 1981, when Ronald Reagan became the fortieth president of the United States. Reagan, who loved speech-making, made things clear on the Capitol steps from which he delivered his inaugural address. “Government,” he said on that occasion, using one of his favorite lines but now speaking about the institution he had just been elected to manage, “is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

-

*

For Nixon fans, another new book may prove satisfying: The Greatest Comeback: How Richard Nixon Rose from Defeat to Create the New Majority (Crown Forum, 2014), a hagiographic account of Nixon’s years after leaving office by his longtime aide and later conservative commentator Patrick J. Buchanan. ↩