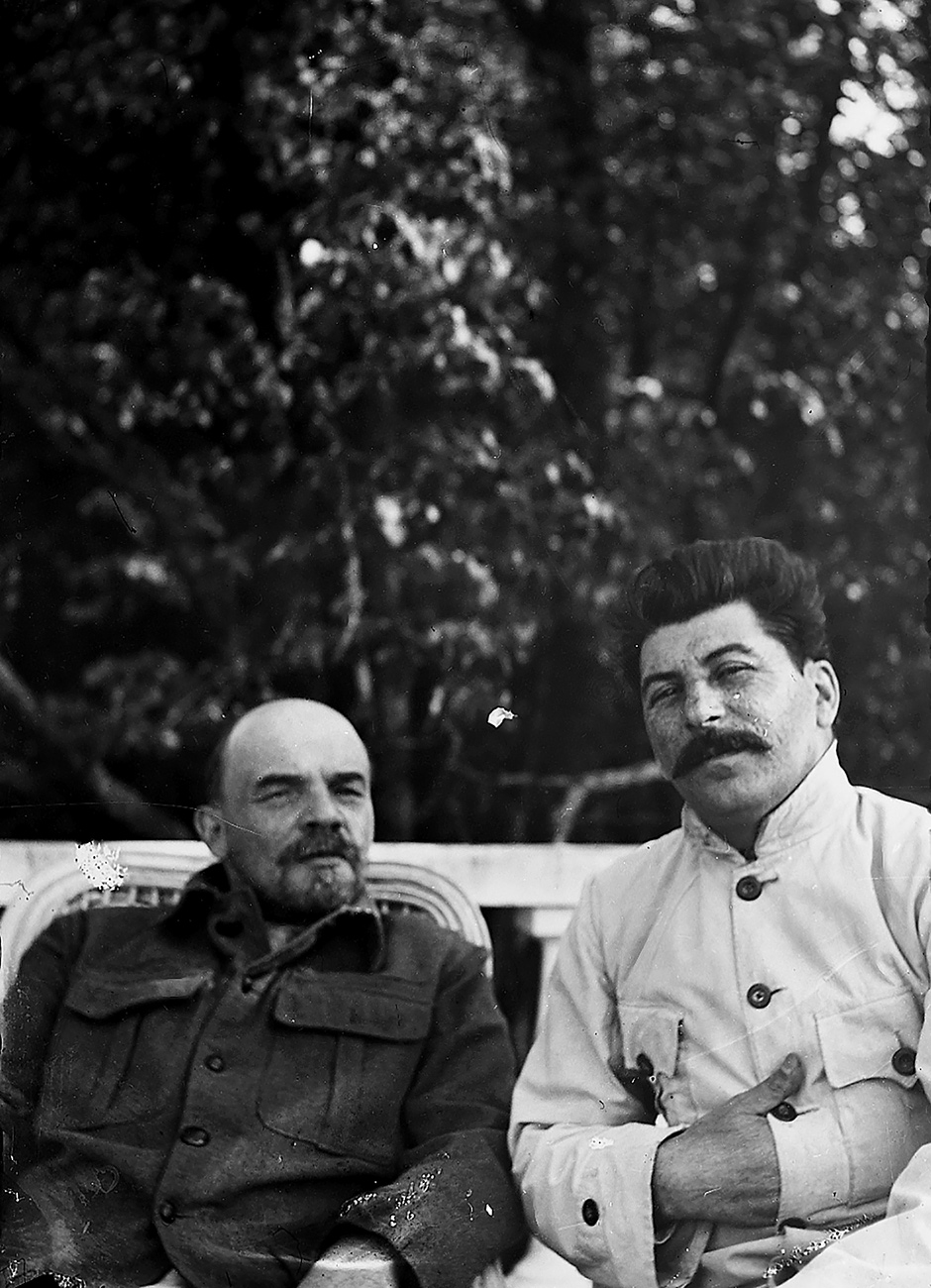

Russian State Archive of Social and Political History (former Central Party Archive)

Lenin and Stalin at Gorki, just outside Moscow, September 1922; photograph by Maria Ulyanova, Lenin’s sister. Stephen Kotkin writes that ‘Stalin had images of his visit published to show Lenin’s supposed recovery—and his own proximity to the Bolshevik leader. This pose was not among those published.’

Joseph Stalin, for a quarter-century undisputed master of the Soviet Union and its postwar satellites, was one of the leading mass murderers of the murderous twentieth century. So much so that Hitler, Stalin’s competitor in this field, came greatly to admire him. In some of his “table talks,” held in the circle of intimate associates while German troops were ravaging the Soviet Union, Hitler called him a “genius” and a “tiger.”*

According to Alexander Yakovlev, a member of the Politburo and the closest adviser of Mikhail Gorbachev, who as chairman of a commission to study Stalinist repressions had access to all the relevant records, Stalin was responsible for the death of 15 million Soviet citizens. He tyrannized over the country as no one had done before. Yet according to public opinion polls, he remains one of Russia’s most popular political figures: a survey conducted in 2006 revealed that nearly one half (47 percent) of Russians regarded him as a positive figure.

What accounts for this paradox? It is that the great majority of Russians have little interest in politics. They regard politicians as crooks and esteem them only to the extent that they protect them from their neighbors and foreigners. Their concerns are not national but local, which means that the majority of them do not participate in politics in the sense in which the ancient Greeks have taught us. Thus when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 after nearly three quarters of a century of unprecedented tyranny, there were neither protests nor jubilations; people simply went about their private business. The lives of the great majority of Russians are uncommonly personal, which makes them excellent friends and poor citizens.

There was nothing in Stalin’s background to have anticipated that he would wield such monstrous power. He came into the world in the Georgian province of the Russian Empire, the child of a cobbler and a washerwoman, both of whom had been born serfs. His actual year of birth was 1878 but in 1922 he decided to rejuvenate himself and proclaimed his birthdate to have been December 21, 1879. Henceforth, as long as he was alive, his birthday was celebrated on that day throughout the Soviet Union. His alleged fiftieth birthday in 1929 was a national holiday.

Harvard University’s library catalog lists over 1,200 books about Stalin. Among the best known of these are the biographies by the French ex-Communist Boris Souvarine (published in 1935) and Leon Trotsky (posthumously published in 1941). Of the more recent biographies, especially noteworthy is that by the Soviet general Dmitri Volkogonov, based on archival sources and originally published in 1988.

Stephen Kotkin, a history professor at Princeton, has issued what he intends to be the first of three biographical volumes. It covers Stalin’s life until 1928, by which time, with Lenin dead and Trotsky exiled, he became the Soviet Union’s undisputed leader. The book is based on an immense number of sources: its bibliography covers nearly fifty pages and lists some three thousand titles. The endnotes encompass 122 pages. The dimensions of the projected biography are explained by the author’s conception of his book as much more than the life of a single man: as he says in the introduction, “in some ways the book builds toward a history of the world from Stalin’s office.”

Following Trotsky’s dismissal of him as “the outstanding mediocrity in our party,” it has been the practice of non-Bolshevik biographers to treat the young Stalin as a nonentity. Kotkin rightly rejects this view, stressing Stalin’s bookishness, his loyalty, his ability to “get things done.” He cites a former schoolmate recalling that Stalin “was a very capable boy, always coming first in his class; he was [also] first in all games and recreation.” “What Trotsky and others missed or refused to acknowledge,” Kotkin writes,

was that Stalin had a deft political touch: he recalled names and episodes of peoples’ biographies, impressing them with his familiarity, concern, and attentiveness, no matter where they stood in the hierarchy….

This in contrast to Lenin’s other close associates, who were mainly bookish intellectuals. On becoming personally acquainted with Stalin in 1905, whom in a letter to Maxim Gorky he would call a “splendid Georgian,” Lenin quickly learned to appreciate Stalin’s abilities as an organizer and increasingly came to rely on him. Even Trotsky had to admit that in 1917 he had “noticed that Lenin was ‘advancing’ Stalin, valuing in him his firmness, grit, stubbornness, and to a certain extent his slyness.”

Advertisement

As a youth, Stalin, known as Soso, was destined for a clerical career and enrolled in a theological school. He performed poorly and in 1899 was expelled from the Tiflis Theological Seminary. By this time he had read Marx and became a fully committed revolutionary. Kotkin describes how he “immersed himself in the workers’ milieu,” getting a job at an oil refinery owned by the Rothschilds and distributing incendiary leaflets. He engaged in illegal activities, including banditry, for which he was arrested in April 1902, and the following year sentenced to three years’ exile in Siberia. He soon escaped his exile and returned to revolutionary work, for which in 1908 he received another sentence of exile, which he again succeeded in escaping. In 1913 he was exiled for the sixth time: he remained in Siberia until the revolution. He was back in Petrograd in March 1917, one month ahead of Lenin.

Before Lenin returned to Russia and called for a decisive break with the Provisional Government, Stalin, unacquainted with Lenin’s thinking, wanted the Bolsheviks to cooperate with the government. Also, unusually for a Bolshevik and quite realistically, he questioned the likelihood of a revolution breaking out in Europe. As Kotkin writes, Stalin would note a few months later that “there is no revolutionary movement in the West, nothing exists, only potential, and we cannot count on potential.”

“Stalin’s role in 1917 has been a subject of dispute,” writes Kotkin.

Nikolai Sukhanov [the author of a seven-volume memoir of the revolution]…forever stamped interpretations, calling Stalin in 1917 “a grey blur, emitting a dim light every now and then and not leaving any trace. There is really nothing more to be said about him.”

Kotkin justly disagrees with this judgment. “Sukhanov’s characterization…was flat wrong,” he writes.

Stalin was deeply engaged in all deliberations and actions in the innermost circle of the Bolshevik leadership, and, as the coup neared and then took place, he was observed in the thick of events.

Stalin’s official post in the new Soviet government was commissar of nationalities. Roughly more than half the population of the Russian state consisted of national minorities. Stalin was the Bolshevik Party’s expert on this subject, having written in 1913, under Lenin’s tutelage, an essay in which he had advocated that the minorities be granted the right to “self-determination” without specifying what exactly he meant by it. But his actual position in the Soviet government was much weightier: a member of the Bolshevik Central Committee since 1912, he was, as Kotkin notes, one of the party’s four “top” people, next to Lenin, Trotsky, and Yakov Sverdlov, as well as editor of Pravda. He was important to Lenin not because of his ideas—Lenin had no need of those—but because of his organizational skills and uncanny ability to deal with people. He had a talent, Kotkin writes, “for summarizing complicated issues in a way that could be readily understood.”

His principal rival was Trotsky, who in March 1918 was appointed people’s commissar of army and navy affairs, in which capacity he directed the Red forces to ultimate victory in the Civil War. Incomparably more sophisticated than Stalin, Trotsky had two strikes against him. One was his prolonged hostility toward Lenin. In the early years of the century he had repeatedly denounced Lenin as a “slipshod attorney,” a “Robespierre” who sought “a dictatorship over the proletariat,” a “malicious and morally repulsive” individual. This hostility was ignored after he joined the Bolsheviks in mid-1917, but the memory lingered. In elections to the Central Committee held at the Tenth Party Congress in 1921, the hero of the Civil War came in tenth, behind Stalin.

The other handicap was his Jewishness. Although born a Jew, Trotsky attached no significance to this fact, on one occasion telling a Jewish delegation that he was not a Jew but an “internationalist.” Yet whatever he thought of himself, he was perceived, in and out of the party, as what Stalin in a personal conversation cited by Kotkin called “a Jewish internationalist.” No Jew had ever held a governmental post in Russia and this was not about to change. Trotsky’s handicap proved Stalin’s boon. In March 1921, Lenin declared that as concerned politics, Trotsky “hasn’t got a clue” and is said to have proposed that he be excluded from Politburo meetings.

In June 1918, Stalin was dispatched to Tsaritsyn on the Volga to gather grain for the central cities. Before long Tsaritsyn was encircled by anti-Bolshevik White armies. Stalin requested and obtained unlimited powers over the city and its garrison; instead of being engaged in provisioning he assumed military command. He acted ruthlessly, shooting many people. Trotsky was dissatisfied with his performance and asked Lenin to have him recalled. The city was eventually won when Dmitry Zhloba, leader of the Bolshevik “Steel Brigade,” led a raid on the White Army. Even though Tsaritsyn was not a glorious page in his career, in 1925 Stalin had it renamed in his honor as Stalingrad, a name the city would bear until 1961 when, following his disgrace, it was renamed Volgograd.

Advertisement

Even after Stalin’s failure to lead the Red Army in Tsaritsyn, his power continued to grow. By the autumn of 1921 he was drafting Politburo agendas and appointing numerous party officials. As Lenin’s health began to deteriorate in early 1922, Stalin felt increasingly secure in his post. In the spring of that year, Lenin proposed and the Eleventh Party Congress acquiesced in having Stalin appointed the party’s general secretary, the chief executive officer of the Central Committee. In this capacity he was Lenin’s heir apparent. Kotkin describes how he “had exceptional power almost instantaneously.” My own researches revealed that during 1922 Stalin was Lenin’s most frequent visitor. He grew increasingly self-confident and began to act on his own initiative, which soon led to a conflict with Lenin.

In 1922 Lenin suffered two massive strokes that gradually eliminated him from public activity. He was installed in a mansion outside Moscow where doctors permitted him only occasional involvement in politics. Though disabled, he watched with growing dismay Stalin’s high-handed behavior and began to wonder whether he had not made a mistake endowing him with such great powers. In December 1922–January 1923, he dictated a document that came to be known as his “Testament.” In it, he wrote as follows:

Stalin is too rude and this shortcoming, fully tolerable within our midst and in our relations as Communists, becomes intolerable in the post of General Secretary. For this reason I suggest that the comrades consider how to transfer Stalin from this post and replace him with someone who in all other respects enjoys over Comrade Stalin only one advantage, namely greater patience, greater loyalty, greater courtesy and attentiveness to comrades, less capriciousness, etc.

This powerful denunciation of Stalin, first published in The New York Times in 1926 (translated by Max Eastman), had to wait thirty years before it became public knowledge in the Soviet Union, following Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin at the Twentieth Party Congress. Subsequently it was included in the fifth edition of Lenin’s Collected Works.

Given these facts, it comes as a considerable surprise to have Kotkin reject the Testament as very likely a fabrication. He refers to it as a document “attributed” to Lenin whose authenticity “has never been proven.” Although Kotkin acknowledges that it could be authentic, he does not clearly accept it as such, as it has been by all other historians; as noted, it is included in Lenin’s Collected Works. Kotkin points to the fact that no stenographic originals of the document exist. But he contradicts himself by citing Stalin’s own references to the Testament and his admission, according to an account by Trotsky of a party meeting, that he was indeed “rude.” Stalin, in whose interest it was to denounce the Testament as a forgery, never did so, as Kotkin himself admits: indeed, he referred to it as “the known letter of comrade Lenin.”

In January 1923 another incident occurred that further alienated Lenin from Stalin. Lenin congratulated Trotsky for having won a battle over foreign trade. Stalin promptly learned of this communication. He telephoned Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin’s wife, rudely criticized her for “informing Lenin about party and state affairs” in violation of the rules he had established, and threatened her with an investigation. Having hung up the phone, Krupskaya became hysterical, sobbing and rolling on the floor. When he learned of this incident several months later, Lenin sent Stalin the following note:

Respected Comrade Stalin!

You had the rudeness to telephone my wife and abuse her. Although she had told you of her willingness to forget what you had said…I have no intention of forgetting so easily what is done against me, and, needless to say, I consider whatever is done to my wife to be directed also against myself. For this reason I request you to inform me whether you agree to retract what you have said and apologize, or prefer a breach of relations between us.

Kotkin does not cite this letter but refers to it as a “purported dictation” because there is no handwritten stenographic copy or any record of the letter having been sent from Lenin’s secretariat, even though it, too, is reproduced in Lenin’s Collected Works.

Finally, there was the Georgian question. In early 1920 Lenin ordered the invasion of Transcaucasia, an area consisting of three sovereign republics, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Given the overwhelming superiority of the Red Army the conquest proceeded smoothly. But once it was completed Stalin and his sidekick, Sergo Ordzhonikidze, began to behave ruthlessly in their native Georgia. Deeply troubled by reports that were reaching him from there, Lenin started to reconsider the whole concept of a Soviet Union. In the last days of 1922 he dictated a memorandum on the nationality question in which he criticized Stalin’s “hastiness and administrative passions” as well as his proclivity for anger. Referring to Stalin’s actions in conquered Georgia, he called him in this document “a crude Great Russian Derzhimorda” or “mug-slammer.”

Kotkin does not cite this document either but simply dismisses it as “a blatant forgery,” although it has been accepted by all historians of the period of whom I am aware as well as the editors of Lenin’s Collected Works.

It is difficult to explain Kotkin’s skepticism of Lenin’s late anti-Stalin diatribes except perhaps by his unwillingness to concede that, supportive as Lenin had been of Stalin until his fatal illness, by the end of his life he had turned resolutely against him. Kotkin admits that statements made by Lenin to his sister corroborate some of the Testament’s contents. But he maintains that the document itself may not have been written by Lenin and suggests that Krupskaya may have been responsible for it, believing that “in her heart she knew Lenin’s wishes.”

This volume ends in 1928, which indeed was a critical year in the history of the Soviet Union. In January Trotsky was exiled to Central Asia from where, the following year, he would be expelled to Turkey and eventually end up in Mexico, where he would be murdered by a Stalinist agent. This eliminated Stalin’s main rival. Then in Siberia, Stalin delivered what Kotkin calls an “earth-shattering speech” in which he announced two revolutionary measures: collectivization and industrialization.

Collectivization would deprive the 100 million Russian peasants of the land they had acquired over the previous century and herd them into collectives in which they would work not as independent farmers but as state servants. It was a return to the Muscovite period when the crown owned all the country’s acreage. The peasants furiously resisted this mass expropriation, destroying crops and killing livestock. Half of Russia’s horses, cattle, and pigs perished in this slaughter. As a consequence, between five and seven million people died from hunger.

Industrialization—in fact if not in theory—was meant to give the USSR a defensive capability necessary for the looming World War II, which Stalin both anticipated and hoped for. Although in principle it was intended to give the USSR a rich, modern economy, in reality it served principally military purposes. After joining the Politburo in the late 1980s, Yakovlev learned to his amazement that 70 percent of the Soviet economy was militarized.

This is a very serious biography that, except for its eccentric denial of Lenin’s rift with Stalin late in his life, is likely to well stand the test of time.

-

*

Hitlers Tischgespräche im Führerhauptquartier 1941–1942, edited by Henry Picker (Bonn: Athenäum, 1951). ↩