Here is an example of how things once worked in Washington. On July 30, 1958, Joseph Alsop, a leading pundit of the day whose column appeared in The Washington Post and the New York Herald Tribune, published an alarming commentary on the missile “gap” he said was about to open up between the Soviet Union and the United States. By the early 1960s, Alsop wrote, “the American government will flaccidly permit the Kremlin to gain an almost unchallengeable superiority in the nuclear striking power that was once our specialty.” Alsop cited statistics on Soviet missile production leaked to him by sources who were disclosing classified information.

Alsop’s friend John F. Kennedy, a fellow resident of the hamlet of Georgetown in Washington and an ambitious senator from Massachusetts, put Alsop’s column into the Congressional Record. Alsop then urged Kennedy to give a speech on the subject, which the senator did on August 14. When the Soviets have achieved clear superiority in intercontinental missiles, Kennedy told the Senate, “the balance of power will gradually shift against us…. [The Soviets’] missile power will be the shield from behind which they will slowly, but surely, advance….”

Then Alsop published two columns in praise of the speech he had promoted. The first, on August 17, described Kennedy as “Massachusetts’ hard-hitting young Senator,” and called his address “one of the most remarkable speeches on American defense and national strategy that this country has heard since the end of the last war.” Alsop wrote that the ominous statistics on future Soviet missile superiority that Kennedy cited—the statistics he took from Alsop’s original column—coincided with information known to senators Stuart Symington (D-Mo.) and Henry M. Jackson (D-Wash.) of the Armed Services Committee that they could not reveal because it was “classified information.” “The voice that faced facts”—Kennedy’s—was “the authentic voice of America,” Alsop wrote.

A second column published the next day closely echoed the first. In case anyone had missed the implication of the first one about the identity of Alsop’s own sources, he spelled it out. There were senators on the floor when Kennedy spoke who knew the classified estimates of future Soviet missile production, Alsop noted, including Jackson and Symington, and none challenged Kennedy’s (really Alsop’s) numbers. “Instead, a whole series of [senators], led by…Symington…and Jackson…, rose to praise Kennedy. They affirmed that he had spoken no more than the truth….”

According to the statistics Alsop cited, by 1964 the Soviet Union would have two thousand intercontinental ballistic missiles, and the US would have 130. These numbers did appear in intelligence estimates—made public years later—that had recently been disclosed to President Eisenhower and a few members of Congress. Alsop had a great scoop. Kennedy, then contemplating a run for the White House, had a great supporter.

But here is another example of how things work in Washington—then, and still today. The scary estimates leaked to Alsop were, as their authors were about to discover, all wet. They were a classic example of worst-case assumptions based on flawed “intelligence.” Photographs taken from high altitude first by the U-2 spy plane and then by the first American reconnaissance satellite would soon lead to radical revisions of the estimates. Instead of scores or hundreds of ICBMs, the Soviet Union had, at most, a few dozen, their reliability unknown. The missile gap and the Soviet strategic advantage attributed to it were myths.

Gregg Herken provides an abbreviated account of this episode in The Georgetown Set, which describes the relationships among an attractive group of World War II veterans who were friends, collaborators, drinking companions, and, in many cases, important government officials, journalists, or politicians. As this anecdote suggests, they lived on what feels today like a different planet, in an America half the size of today’s and in a Washington that John le Carré easily and accurately could have described as a small town in America. That America was under the sway of an Anglo-Saxon elite from the Northeast that fancied itself a governing class. In some respects it really was a governing class; in others its pretensions were not matched by its true importance.

Herken’s dramatis personae were a colorful lot. They include Kennedy; Joseph Alsop and his brother Stewart, first famous for their sharp critiques of Senator Joseph McCarthy; Frank Wisner, Richard Bissell, and Richard Helms, all founding fathers of the CIA; Philip Graham and his wife Katharine, who in turn were publishers of The Washington Post; Felix Frankfurter, the Supreme Court justice; Llewelyn “Tommy” Thompson and Charles “Chip” Bohlen, the two career foreign service officers and Soviet experts who helped JFK through the Cuban missile crisis; George F. Kennan, the brilliant and neurotic Soviet specialist and historian; Isaiah Berlin, the Russian-born Oxford don who became one of the more respected intellectuals of his time and a frequent visitor to Georgetown; Walter Lippmann and James “Scotty” Reston, the two leading pundits of the cold war era; Robert Oppenheimer, the nuclear scientist in charge of creating the hydrogen bomb who opposed building it and ultimately lost his security clearances; and John Paton Davies, a China expert in the foreign service and a leading victim of Senator McCarthy’s witch hunts.

Advertisement

Because so many of them knew, liked, and helped one another, these people provided useful lubricants to the processes of governing in difficult times. Herken somewhat awkwardly, but also entertainingly, brings them all together in what he calls the Georgetown set, a term of uncertain origin used in previous books that have covered similar ground.1 Not all of them lived in Georgetown or would have seen themselves as members of a “set,” but Herken seems content to perpetuate an imperfect description.

Herken was obviously beguiled by these characters, none of whom he appears to have known personally. But he also seems uncertain about how to describe their contributions to the cold war era. The conclusions he offers are contradictory. On one hand he describes “a coterie of affluent, well- educated, and well-connected civilians” who “inspired, promoted, and—in some cases—personally executed America’s winning Cold War strategy.” He writes of “the Georgetown Set’s success in coping with—and ultimately triumphing over—a determined enemy imbued with a fanatical ideology.”

But Herken also, accurately, refers to the three greatest accomplishments of “the famed postwar bipartisan consensus of Republicans and Democrats”—the Truman Doctrine, the Marshall Plan, and NATO, all critically important to America’s ultimate cold war successes. Herken’s Georgetown set were mostly cheerleaders for—not architects of—those momentous developments. And he offers another account of the contributions of these people at odds with the exultant versions quoted in the previous paragraph:

The Georgetown set also bears no slight responsibility for the miscalculations and disasters of that era: the danger, profligacy, and waste of a runaway nuclear arms race; reckless and costly clandestine adventures overseas; complacency in the face of political reaction at home; and, not least of all, the protracted debacle of Vietnam.

Were they heroic, or culpable malefactors? Herken never answers the question. In the end he avoids any broad conclusions; his book is a series of sketches. His contradictory impressions of the cold warriors he writes about are not unusual—as a society we have not come to any clear conclusions about the cold war. We “won”—or the Soviet Union “lost”—but that is hardly the whole story. Herken’s list of miscalculations and disasters barely begins a serious enumeration of the cold war’s costs for the United States and for the countries where the cold war took our spies and soldiers. It seems possible, even probable, that in years to come the costs will loom larger than the sense of triumphalism brought on by the collapse of the Soviet empire a quarter-century ago.

Of all the beguiling characters Herken introduces, he is most taken with Joseph Wright Alsop, a unique twentieth-century American. Born to blue bloods in Avon, Connecticut, in 1910, educated at Groton and Harvard, and a member of Harvard’s then-snooty Porcellian Club, Alsop came to Washington in the 1930s as a journalist, a rare WASP aristocrat in the capital’s press corps. He happily exploited his access to his cousins Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt and established himself as a man about town. Since childhood Alsop had been overweight; in Washington society, to which he had easy entree in the 1930s, he was known as a charming fatso. A medical scare in 1937 prompted him to lose sixty-five pounds, reducing his waist by twelve inches.

Alsop’s suits, shirts, and shoes were made for him in London (and later Hong Kong). From a young age he affected a vaguely English manner of speech. For the last half of his life he wore oversized, round eyeglasses with thick, dark plastic frames that he often allowed to slide down his large nose. He devoured history, high culture, champagne, and gin. He loved parties and conversation. He was eager to share his strong opinions on nearly all subjects, sometimes in a bullying manner that could infuriate his interlocutors. Reston once called him “a cruel man.” The sometime bully was also a deeply closeted homosexual, which he never discussed (although Soviet intelligence, as Herken writes, tried to blackmail him). And he was always a hardworking reporter who broke stories, a talent he honed for decades. The complex eddies of his mind and personality baffled both friends (there were many devoted ones) and enemies (also a great many).

Isaiah Berlin first met Alsop in the early 1940s, when Berlin came to New York to work in his government’s propaganda office there. In a letter to his parents in 1941, Berlin described his new friend as “a fanatical Anglophile, intelligent, young, snobbish, a little pompous, and my permanent host in Washington.” Their friendship lasted until Alsop died in 1989; Berlin flew to Washington for his funeral.

Advertisement

Alsop’s gift for friendship helped him practice his favored brand of Washington journalism. Herken, aptly, calls it “access or elite journalism, which was almost wholly dependent on news leaks and privileged entrée to Washington’s policy makers.” Alsop mastered this art form in pre-war Washington, when his cousins occupied the White House and New Dealers tended to be the most interesting and amusing people in Washington—and the most powerful. The Truman years were a little trickier, but Alsop’s personal connections still provided a steady stream of scoops, the lifeblood of the column he and Stewart wrote together, “Matter of Fact.” By the late 1940s, when Herken’s story begins, Alsop’s dining room table was a center of Washington life, the chairs regularly occupied by other members of the Georgetown set, prominent diplomats, members of Congress, and other journalists.

When the Eisenhower administration arrived in 1953, the new president and his people rebuffed Alsop’s efforts to establish special relationships with them. One was Eisenhower’s national security adviser, Robert Cutler, a Porcellian man at Harvard fifteen years before Alsop whom the columnist hoped to make a regular source. Herken quotes Cutler’s account of Alsop’s approach to him: “By periodically outlining background material I could provide enough orientation to make his column an authoritative, but of course anonymous, spokesman for the President.” But Cutler was not charmed. He bluntly told Alsop to get his news from Eisenhower’s press secretary.

Joe stewed on this overnight, then wrote Cutler a letter: “I cannot refrain from writing to give you my opinion, as a friend and not as a newspaperman, that you are making a very great mistake.” The letter had no effect. Alsop never became a confidant of the Eisenhower White House, and soon became its fierce critic.

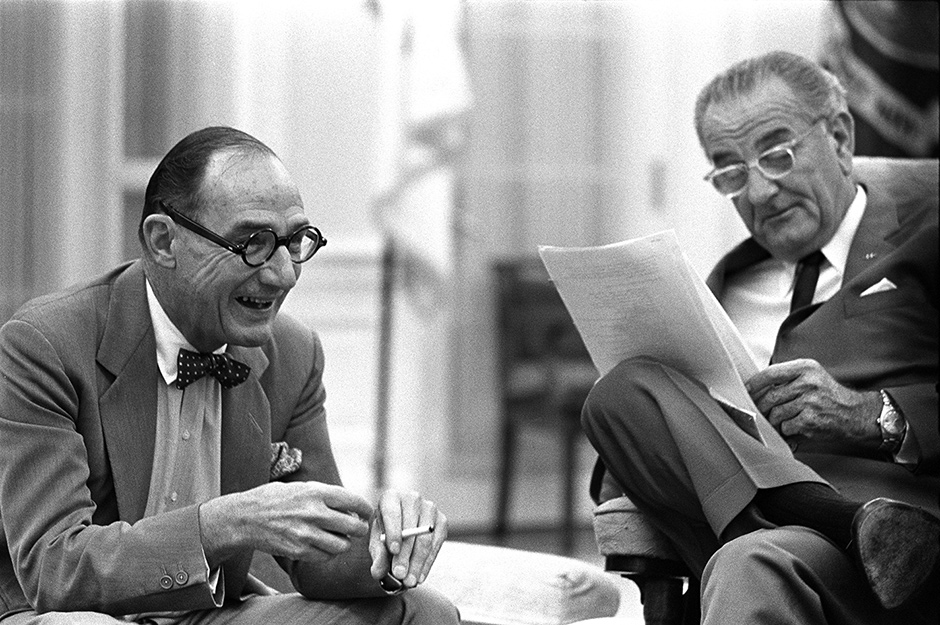

Kennedy was a different case entirely, beginning in the first hours of his presidency. The young president (forty-three when he was inaugurated) decided to make a friend of Alsop (then fifty), who was thrilled to reciprocate. Alsop became an informal adviser to the Kennedy campaign, a violation of all journalistic standards, and then its cheerleader in print—a worse violation. At about two AM on the night of his inauguration, still in white tie and tails, Kennedy showed up at Alsop’s house at 2720 Dumbarton Street (not Avenue, as Herken writes repeatedly) in Georgetown and drank champagne until after three. Word of this unconventional visit spread quickly around the village that was Washington; soon everyone knew the identity of the new president’s favorite journalist.

The intimate interaction between press and president in the thousand days of John F. Kennedy’s administration had no precedent, and has never been repeated. It depended on the existence of a like-minded cohort of World War II veterans (soldiers and journalists who covered the war) who shared a view of America’s destiny as the new superpower that would have to manage an unruly world. It also depended on John F. Kennedy’s self-confidence and guile. Kennedy played the press like a pipe organ.

He cultivated (among others) Lipp mann and Reston; Arthur Krock of The New York Times, who had been Joseph P. Kennedy’s close friend and promoter since 1934; Marquis Childs of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch; his old pal Charles Bartlett, Washington correspondent of the Chattanooga Times; Benjamin C. Bradlee, Washington bureau chief of Newsweek and Kennedy’s neighbor on N Street in Georgetown. Many of these people became Kennedy’s real friends. They provided laughs, companionship, and a good deal of political advice. Getting so close to a politician was not professional, most seemed to understand, but it certainly was fun. “If I was had,” Bradlee wrote years later, “so be it.”

Sometimes Kennedy used the relationships he built with journalists to conduct serious business. One striking example was the interview he gave Reston in the American embassy in Vienna just moments after Nikita Khrushchev had finished bullying him mercilessly at their summit meeting in June 1961. At the same time his spokesman and other aides were telling reporters that the conversation between the two leaders had been uneventful and “amiable,” Kennedy was admitting to Reston that Khrushchev had come after him aggressively, obviously believing he was too young and callow to be taken seriously. As Kennedy expected, Reston used this interview (without quoting Kennedy) to tell the world that the summit had featured “hard controversy” and “sharp disagreements,” foretelling difficult days ahead. (Alsop was also on the trip to Vienna; he completely missed the story, catching up days later.)

Kennedy’s intimate relations with journalists came to mind watching Barack Obama’s year-end news conference this past December. Near the end of that event, reading from a prepared list of White House reporters, Obama called on “Juliet Eyesprin,” mangling the name of Juliet Eilperin, a Washington Post reporter who covers Obama’s White House every day. No surprise there—Obama has no close personal relationships with Washington journalists. Neither did George W. Bush or Bill Clinton. The modern presidency is an elegant, elaborate isolation booth.

Washington from 1945 to 1965 provided a fascinating spectacle. The dramas were intense and consequential; the personalities were large. It is easy to see why Herken was attracted to these people and their doings. His book does not give us much new material or any striking new insights, but many will find it fun to read, because it brings back a captivating world that existed quite recently, but is already ancient history. The book may also frustrate some who find its author a rather dry historian whose characters deserve the talents of a gifted novelist. None of them really comes alive in these pages. Herken misses opportunities to paint fuller portraits of these complicated personalities. For example, Alsop’s aesthetic sensibilities, so important to him personally (he published carefully researched books about Greek bronzes and the history of art collecting) are barely mentioned.2

The heyday of the Georgetown set ended with the Vietnam War, an avoidable catastrophe that has done immeasurable damage to this country, and particularly to the tradition of New Deal liberalism that Truman, Kennedy, and many of Herken’s characters tried to sustain. That tradition has now largely disappeared from our politics. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, two Democrats who felt allegiance to FDR themselves, gave us the Vietnam War, which destroyed the country’s confidence in its government. That confidence has never been revived.

With few exceptions—George Kennan was one of them—most members of Herken’s Georgetown set initially supported the Vietnam War. For them and many other members of the World War II generation, Vietnam became a test of character. Did we learn the lesson of Munich or not? We did the “right” thing in Korea, now we must do it again in Vietnam. That was the line, embraced by numerous right-thinking worthies, including many liberal Democrats. Tragically, it left no room for the realities of Vietnam and its history, which did not fit the cold war narrative that the war’s proponents propagated.

There was no more ardent or articulate promoter of that narrative than Joseph Alsop. He was wrong about Vietnam from the very beginning. That came for him on his first trip to Indochina in December 1953, shortly after the armistice that divided Korea in two. Alsop was alarmed by what he found—an outgunned French army in danger of losing to Ho Chi Minh’s Communist Vietminh. A remote French outpost at Dien Bien Phu, near the Laotian border, was, Alsop concluded, a strategic location of great importance. He was right about that—the battle of Dien Bien Phu, which began several months later, proved to be the climactic battle in the Vietnamese war for independence. “The loss of Indo-China,” Alsop wrote in January 1954, “will be the prelude to the loss of Asia.”

Such pessimism was characteristic of Alsop, whose depressive psychology seemed often to dominate his analysis. Herken quotes a telling letter Alsop wrote to his wartime boss, Claire Chennault, in February 1946, describing postwar Washington:

Everything is awful here. The Administration is weak and seems to grow weaker by the day. The world situation is already appalling, yet appears to be deteriorating further with great rapidity. The Russians seem to me very likely to win the ball game, and no one here has any remedy in mind but further appeasement. God help us all.

Alsop retained this fundamental gloominess until the end of his days.

After Vietnam was divided by the 1954 Geneva agreements, Alsop became an enthusiastic supporter of Ngo Dinh Diem, the strange man who was Washington’s choice to run the new Republic of South Vietnam. Alsop fervidly supported American assistance for Diem, and Kennedy sent more than 16,000 military “advisers” to try to help his army fight the Communists who had launched a guerrilla war against the new regime in the south.

Later, after personal dealings with Diem and his brother convinced Alsop that both men were disconnected from reality, he personally warned Kennedy that they were doomed. We don’t know if Alsop’s advice played a part, but at about the same time, Kennedy approved US support for a military coup in Saigon that ended with the assassinations of the Ngo brothers—and a deeper American commitment to South Vietnam. By the time Johnson launched a full-scale ground war in 1965, Alsop was the most prominent and outspoken hawk writing for major American newspapers.

As the war effort dragged on and the country divided into bitter factions supporting and opposing it, the world of the Georgetown set was torn asunder. In 1969 the war became Richard M. Nixon’s, and many of its early supporters became its critics. Not Joe Alsop. He continued to visit South Vietnam twice a year, and always found a basis for optimistic columns on the course of the fighting. By 1970, his heavy drinking had rendered him a useless reporter in the field, but his course was set, and he never abandoned it. Herken quotes John Kenneth Galbraith’s observation that Alsop was, “second only to Lyndon Johnson,…the leading non-combatant casualty of Vietnam. From being a much-feared columnist, warrior and prophet he has become a figure of fun. It was the war that did him in.”

Forty years after that war ended in humiliating defeat, Alsop’s fate looks anything but singular. The “protracted debacle” of the Vietnam War, as Herken calls it, did in a lot more than Joseph Alsop and the Georgetown set. The war was the great tragedy of post-war America.

This Issue

March 5, 2015

Vaccinate or Not?

Our Date with Miranda

France on Fire