When Henry Roth’s debut novel, Call It Sleep, was published in 1934, critics judged it second as a work of fiction, and first as a work of anthropology. An autobiographical account of immigrant Jewish life on the Lower East Side, the book was praised in the New York Herald Tribune as “the most accurate and profound study of an American slum childhood that has yet appeared”; the New York Times reviewer wrote that it “has done for the East Side what James T. Farrell is doing for the Chicago Irish.” The New Masses, a Marxist journal, debated whether the novel was sufficiently revolutionary. This arid political criticism might have contributed to killing it off, for the novel was out of print by 1936.

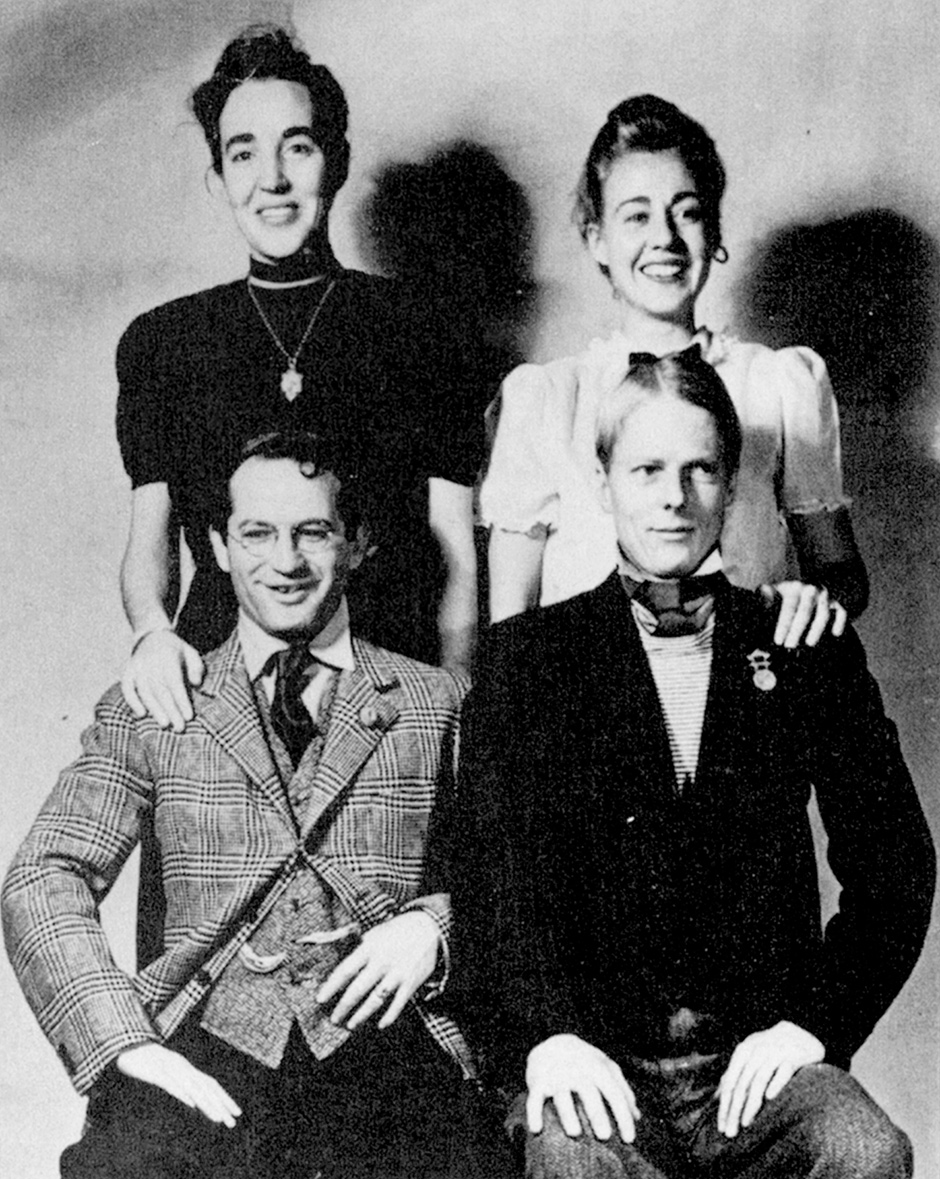

When it was republished as an Avon paperback in 1964, it was the mysterious fate of the author, who at that point had never completed another novel, that captured the public imagination. Championing Call It Sleep on the cover of The New York Times Book Review, Irving Howe led with a discussion of the novel’s precarious “underground existence” and “vague rumors” that Roth had become a “duck farmer in Maine.” Within the week Call It Sleep had sold more than ten times the number of copies it had sold in the previous three decades, on its way to selling more than a million copies. This came as a shock to Roth, who, after stints as a psychiatric hospital orderly, precision tool grinder, English teacher, and maple syrup vendor, was in fact a waterfowl farmer in Montville, Maine.

Roth’s legend grew with profiles, to which he reluctantly submitted, in national magazines that, as his biographer Steven Kellman put it, “contributed to the myth of Henry Roth as the Rip Van Winkle of American literature.”* Roth did not awake from his long professional slumber until 1994, with the publication of A Star Shines Over Mt. Morris Park, his first novel in sixty years and the beginning of a four-volume saga called Mercy of a Rude Stream, which has now been published for the first time in a monstrous volume of 1,279 pages, nearly twenty years after his death in 1995.

The book comes with endorsements comparing Roth to Balzac (from Cynthia Ozick), Nathanael West (Harold Bloom), and Philip Roth (Bloom again, as well as Joshua Ferris, in his introduction to the edition). Roth bears resemblances to these writers, to be certain: he shares Philip Roth’s agonized sense of humor, Balzac’s interest in sociological detail, and West’s fascination with the grotesque. But the publication of the complete Mercy of a Rude Stream is an opportunity to appreciate how sublimely strange Roth’s masterpiece is. It is not remotely like anything else in American literature.

Even though Roth had repeatedly renounced Call It Sleep (“The man who wrote that book at the age of twenty-seven is dead,” he told interviewers), A Star Shines Over Mt. Morris Park continues where the previous novel left off—in the summer of 1914, with Roth’s eight-year-old hero moving with his family from the Lower East Side to Jewish Harlem. Roth’s alter ego, David Schearl in Call It Sleep, has been renamed Ira Stigman, but like Schearl he is an only child, Galicia-born. His parents, Genya and Albert, have become Leah and Chaim, which happen to be the names of Roth’s own parents. (“Genya,” oddly, is the name given to one of Leah’s sisters, whom we learn will later be killed in a concentration camp.) Ira’s parents are not identical to their predecessors; they are more complex, richer. Chaim, like Albert, is a milkman, though he is not nearly as cruel, possessing a self-deprecatory streak that humanizes him; Leah, while as excessively devoted to her son as Genya, is less beatific and a stronger adversary to her husband.

Though six decades have passed between novels, readers will find the same cold-water flat with the same green oilcloth–covered table, the same arguments about money, the same florid Yiddish imprecations. Several episodes are repeated nearly intact, including the attempted seduction of the narrator’s mother while she is left alone with her son (in Call It Sleep, the suitor is Albert’s coworker; in Mercy, he is Leah’s adult nephew). The novel also borrows a striking linguistic inversion from Call It Sleep: when the immigrant parents use Yiddish, their speech is articulate, sophisticated, even poetic, while their English is broken and addled, full of solecisms. They possess a dignity that their destitute, overcrowded apartments, which they share with legions of brazen vermin, cannot entirely diminish.

Advertisement

Stylistically, however, the tetralogy is the work of a different writer. In Call It Sleep, David Schearl is trying to make sense of a new world—the new world—that is baffling, dangerous, and chaotic. It is “a fable,” as Roth later put it, “of discontinuity.” Mercy of a Rude Stream, on the other hand, is compulsively continuous. No memory goes unrecorded. The approach is more than nostalgic; it is custodial. We are in the mind of a dying man struggling to remember every possible detail about his childhood, before they all follow him into oblivion.

For most of the first volume, the story advances creakily, haltingly. Sections are introduced like journal entries: “It was a February day, the first week in February, 1918.” “Once again it was summer, the early summer of 1919.” “And finally came 1920….” During these years Ira meets a series of charismatic boys to whom he attaches himself in the hope of escaping the loneliness of his solitary home life, and there are occasional scenes of intense emotion: Ira is molested by two different men, a stranger and a teacher; an uncle comes home from war and, in his anxiety, bites into a drinking glass; Ira steals an expensive pen from another student, lies about it, and is expelled.

But these dramatic interludes sneak up on the unprepared reader, who is lulled into submission by descriptions of every teacher, every class, every report card (“He was promoted, with B B B on his report card”). Often Roth seems to cast around, free-associatively, as if brainstorming, for details he might have forgotten. The memories have anthropological interest, but no clear significance to the novel:

If you went to the movies, alone and on Saturday, it was better to go there with three cents, and wait outside for a partner with two cents….

A Star Shines Over Mt. Morris aims for comprehensiveness—and yet something is missing. It feels as if Roth is stalling for time. As we will learn in the next volume, he is. Something is missing, all right.

The first volume is redeemed by images of crystalline beauty—“rowboats floating on spangles of water” in Central Park, steel-shod horses “suddenly skating in mid-stride” on the “long, icy ribbons” of frozen avenues—and Roth’s own awareness of his narrative’s shortcomings. This self-lacerating commentary is introduced through the first of Mercy’s two major narrative innovations: a second narrative, set some seventy years later, in which Ira is an elderly man. Appearing at irregular intervals and rendered in a different typeface, these passages are initially unwelcome disruptions, especially as the story struggles to gain momentum. Even Roth agrees: “If only there weren’t so many interruptions,” he carps, “so many distractions.”

These interruptions are difficult to characterize: some appear in the first person, some in the second, some in the third. Many are dialogues between Ira and his computer, whom he addresses, with self-conscious pretension, as Ecclesias. They range from a sentence or two to digressions that go on for a dozen pages. Some take place in 1979, the year that Roth (and Ira) began writing the novel; others take place as many as fifteen years later when, near death, he is making his final revisions.

We learn gradually, in bits and pieces of allusive, evasive prose, that Ira has a wife, M., whom he loves deeply and gratefully; that he now lives in a trailer park in New Mexico; that he is the author of a single novel, published in 1934; and that his “extraordinary hiatus of production…was the dominant feature of his literary career.” At several points in the first volume he refers, vaguely, to an “omission” in the narrative, but we never know whether this is important or merely another digression.

The interruptions assume greater significance as we realize that the novel’s central drama lies not in the misadventures of young Ira, but in old Ira’s effort to turn his life into literature. A tension develops between the Ecclesias sections and the main story, as the older Ira grows frustrated with the limitations of his style—even before the reader does. Fifty pages in comes the admission that the stories from his youth

should have gone into a novel, several novels perhaps, written in early manhood, after his first—and only—work of fiction. There should have followed novels written in the maturity gained by that first novel.

—Well, salvage whatever you can, threadbare mementos glimmering in recollection.

What begins as a young man’s coming-of-age novel turns out to be an old man’s coming-to-sober-terms-with-death novel. Why, Ira wonders, this compulsion to write everything down? Is it really, as he tells Ecclesias at one point, “to make dying easier”? Or is it to understand something crucial about his identity? He believes that his family’s decision to leave “the Orthodox ministate of the East Side” for Harlem led to an irreversible “attrition of his identity.” The question of identity, he decides, is inseparable from his Jewishness. As a child he hated being a Jew, felt imprisoned in Jewishness, and as an adult he has responded by becoming a devoted atheist (“Marxist-Socialist atheism offers the only salvation”). But the act of writing about his youth forces him to realize that his Jewishness is the source of his creative impulse. “When he tried to pluck it out,” he writes, “creative inanition followed.” So perhaps the meticulous exhumation of his past is actually an attempt to understand what drives him—and us all—to create works of art.

Advertisement

Or perhaps this is all a cover. Perhaps something else is going on.

Something else is going on.

What it is, exactly, is revealed 122 pages into the second volume, A Diving Rock on the Hudson. Until this point we have continued to coast along the contrails of Ira’s memory: expulsion from Stuyvesant High School, a series of menial jobs—office boy at a law firm, clerk at a toy company, a soda pop vendor at the Polo Grounds—transfer to DeWitt Clinton High School, and an encounter with a young black prostitute. In the Ecclesias sections, we’ve learned that excerpts from A Star Shines Over Mt. Morris Park have been refused for publication by “various and sundry well-thought-of periodicals,” a rejection that he concedes is deserved:

His stuff was now old hat…waning and wanting, and perhaps pathetic. Be better, more dignified, if he shut up, maintained an air of remote reserve, because that way his deficiencies would remain unexposed. Good idea.

Then, shortly after a summation of his junior year report card (“A, A, A, every quiz, every test”), with Ira lying in his bed on a Sunday morning while his mother goes shopping, we encounter two nonsensical words of dialogue: “Minnie. Okay?”

There has not been any previous mention of a Minnie, so why a woman named Minnie should be inside the Stigmans’ small apartment is baffling. Not as baffling, however, as what follows:

She said all kinds of dirty words at first; where did she learn them? After he showed her how different it was, “Fuck me, fuck me good!” He wished she wouldn’t, though he liked it.

There follows a page of hard-core raunch. This is the least of it:

She slid out of her folding cot, and into Mom and Pop’s double bed beside it; while he dug for the little tin of Trojans in his pants pocket, little aluminum pod at two for a quarter. And then she watched him, strict and serious, her face on the fat pillow, her hazel eyes, myopic and close together—like Pop’s—watched him roll a condom on his hard-on…. “Fuck me like a hoor. No, no kisses. I don’t want no kisses. Just fuck me good.”

In case there was any doubt, that second reference to “Pop” seals it. Minnie is Ira’s kid sister. As we later learn, they’ve been having sexual relations for four years, since Minnie was ten. But this information isn’t revealed at once, so we’re left to wonder if somehow, in 389 pages of anatomical description of every object in the cold-water apartment—every tablecloth and bathroom fixture and family portrait hanging on the wall—and of every activity Ira has experienced between the years of eight and sixteen, we might have missed the fact that Ira has a sister, and is regularly having sex with her. It is one of the most deranged moments in American fiction.

It also turns everything that’s come before it into a lie—including, if we are to read it as a work of memoir, Call It Sleep. David Schearl, like Ira Stigman, is an only child. The closest Roth comes in the earlier novel to revealing his secret is a scene in which a friend’s sister drags Schearl into a closet and gropes him. “I managed to evade [it] in the only novel I ever wrote: coming to grips with it,” says old Ira, in Mercy of a Rude Stream. “You made a climax of evasion,” replies Ecclesias, “an apocalyptic tour de force at the price of renouncing a literary future. As pyrotechnics, it was commendable.” But pyrotechnics and nothing more. The evasion in his first novel, Ira believes, was responsible for his writing block.

We also realize that, in the earlier parts of Mercy of a Rude Stream, what seemed a compulsion to disclose every detail of his youth was in fact a compulsion to erase every trace of his sister. It’s the liar’s first pantomime: tell everything, show nothing. Roth, it turns out, is not a laborious chronicler of lost time, but a trickster. Minnie’s sudden appearance forces us to question everything. For instance: Was Ira really so lonely after all? Doesn’t seem like it! Is he telling this story in order to come to terms with death, or with his own original sin? Might the “attrition of his identity,” his profound sense of alienation, relate not to Manhattan geography but to shtupping his sister and keeping it a secret for seventy years?

When volume two was published in 1995, Roth told interviewers that the incest, like most everything else in the novel, was drawn from actual experience. (His sister Rose, still alive at the time, issued a denial and threatened to sue his publisher; she settled with her brother for $10,000.) For literary critics incest replaced the “extraordinary hiatus” as the dominant feature of Roth’s literary career. But because the two final volumes were not yet published, it was impossible to see how the revelation transformed the substance of the novel itself. It was not appreciated that Minnie appears at the one-third mark of his story—the end, in conventional drama, of the first act.

After the revelation, it is as if the novel begins anew. Though we remain at the mercy of the chronological stream, the prose is livelier, the Ecclesias sections crackle with equal parts self-loathing and elation, and, for the first time, the story possesses momentum and suspense. Roth is liberated by his disclosure, free at last to move beyond childhood and into the thornier questions that arise with sexual maturity—particularly Ira’s sexual maturity. “I must admit that I come to life,” he writes, “when in the grip of the sexual escapade.” It is true that after nearly four hundred pages of chores, games with neighborhood children, and report cards, the incest scenes are a lively addition.

But the rest of the narrative is livelier too. His incestuous relationship, like “a dark binary star on a visible one,” has “altered the entire universe” of the novel. A life is now at stake. Ira is a man with a horrific secret, which is “the determining force in Ira’s thoughts and behavior.” It influences every decision he makes—from his choice of college to his desire to become a novelist. We need Ecclesias now, to serve as a guide through the tenebrous, overgrown forest of Ira’s mind.

Buried in the second volume, not long before Minnie’s appearance, is a short anecdote about Ira’s discovery of Wagner’s “Prize Song,” from Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. It mystifies him when he hears it on a friend’s phonograph one aimless afternoon. After playing the song repeatedly, “with a tenacity born of sheer anomie,” what he originally perceived as cacophony becomes

deliberately ordered sounds, not just ordinary harmony, but unique sounds and cadences that once comprehended became inevitable…. So that’s what they meant by great music. After a while the music went through your head. It was a different kind of tune, altogether different at first, but it slowly became familiar, and when it became familiar, it sang—in its own way, and yet it was right.

That is exactly what it’s like to read Mercy of a Rude Stream.

It is one of the perverse satisfactions of the novel that Ira, despite his deep feelings of shame, writes shamelessly about the thrill of incest. It is a “glorious abomination,” “the jackpot of the transcendental abominable”:

Better, more obsessively sought after, for being a sin, an abomination! Boy, that fierce furor, with her alternately foul and tender outcries of the essence of wickedness…. He wouldn’t miss it, exchange it, for anything else in the world.

Even years later, long after they have concluded their affair, he admits desiring Minnie still. Yet Ira is painfully aware of how his desire cripples him, warps him, stunts his growth, and turns him inward. He is immured by his sexual appetite, “appetite always morticed to fear and self-reproach.” His life shrinks to the size of his incestuous compulsion. His sin infantilizes him, keeps him in a perpetual tawdry adolescence. He feels that he’s been ruined for adult relationships, and adult responsibilities. And like any obsessive, he can’t stop. Not long after Ira and Minnie finish their affair, he starts a new one with Stella, his pudgy fourteen-year-old cousin.

Ira can only observe the world of adults from the outside, like a spy. He gets an opportunity to do so in the final two volumes—From Bondage and Requiem for Harlem—when his best friend, Larry Gordon, begins an affair with Edith Welles, a pretty adjunct English professor at NYU. Larry, like so many of the boys Ira has befriended, is everything Ira wants to be, and isn’t: wealthy, handsome, articulate, culturally savvy, supported by a loving family that is generations removed from the shtetl, so assimilated that the fact of their being Jewish comes as a shock to Ira. Edith hopes to mold Larry, who has bohemian aspirations, into a poet. But Larry cannot produce lines. In his frustration he turns to sculpture, but he fails here too.

While Larry despairs, Ira, his clumsy sidekick, wins a story competition at CUNY, and Edith begins to shift her allegiance. As Edith and Ira draw closer together, he confesses his dark secret; to his surprise, Edith does not reject him, but sympathizes with him. She encourages him to liberate himself from the bondage of his compulsive depravity through literature. Returning from a trip to Europe she gives him a contraband copy of Ulysses, and in James Joyce’s novel, and later in the poetry of T.S. Eliot, Ira glimpses his future. Literature, he decides, can offer him “a way of buffering, of screening out, reality.” Through fiction he can rewrite his past. He can erase his sin. He can erase his sister. And his fourteen-year-old cousin, while he’s at it.

In the Ecclesias sections, meanwhile, old Ira refines his personal theory of literature. Characteristically it is full of contradictions. Some 750 pages into the novel he is still questioning himself, his narrative strategy, and the self-imposed exile that has swallowed up his career. Even as, in the main narrative, young Ira is discovering Joyce for the first time, in the second narrative old Ira is renouncing Joyce for abandoning his folk and abstracting their struggles into a narcissistic aesthetic exercise. Ira credits the richness of his immigrant childhood with inspiring him to create, in his first novel, “a fable that addressed a universal experience, a universal disquiet” that reverberated so deeply with readers. Yet at the same time he argues that his failure, and the failure of so many writers of his generation, lay in an inability to mature—“to align themselves with the future.”

Ira’s (or Roth’s) motivations for undertaking such an ambitious and peculiar novel as Mercy of a Rude Stream are just as conflicted. He claims, variously, that he is writing in order to “transmogrify the baseness of his days and ways into precious literature…[to] free him[self] from this depraved exile”; simply for the love of “creating something worthwhile”; to “help others avoid the pitfalls he had been prone to”; to impose order on his chaotic inner life; to celebrate his life’s disorderliness; “to ward off time”; “to make dying easier, more welcome, for myself and my fellow man”; and to tell future generations “what it was to be alive” in Harlem at the turn of the century. There’s nothing unusual about having more than one reason to write a novel, or to undertake a literary career. What is unusual is the author’s profound sense of turmoil as he struggles to organize his own thoughts. He is tortured by the way “contradictions within the self made you feel, as if you had lost all your substance, were hollow.” But he also realizes that “acknowledging his own contrarieties reunited him within himself.”

It is this pitiless examination of a writer grappling with his demons, at the highest reaches of his intellectual capacity, that gives Mercy of a Rude Stream its ferocious passion. This kind of self-questioning approach, as many other readers of Roth have pointed out, is as old as the Talmud, which he quotes in the epigraph of the novel’s final volume:

Without Haste, Without Rest.

Not thine the labour to complete,

And yet thou art not free to cease!

Really no other justification is needed. Ira writes despite his inadequacies and self-doubt, despite the fact that he doesn’t expect to finish the novel, or even for it to be read. There is folly in this, but also heroism. Mercy of a Rude Stream asks absolute questions and fails to answer them, as all powerful literature must do. If the novel is overlong and overstuffed, its prodigality is justified—it is an expression of the exhilaration felt by a man who has cast off six decades of self-repression and finally feels himself free.

-

*

Steven G. Kellman, Redemption: The Life of Henry Roth (Norton, 2005), p. 232; reviewed in these pages by Daniel Mendelsohn, December 15, 2005. ↩