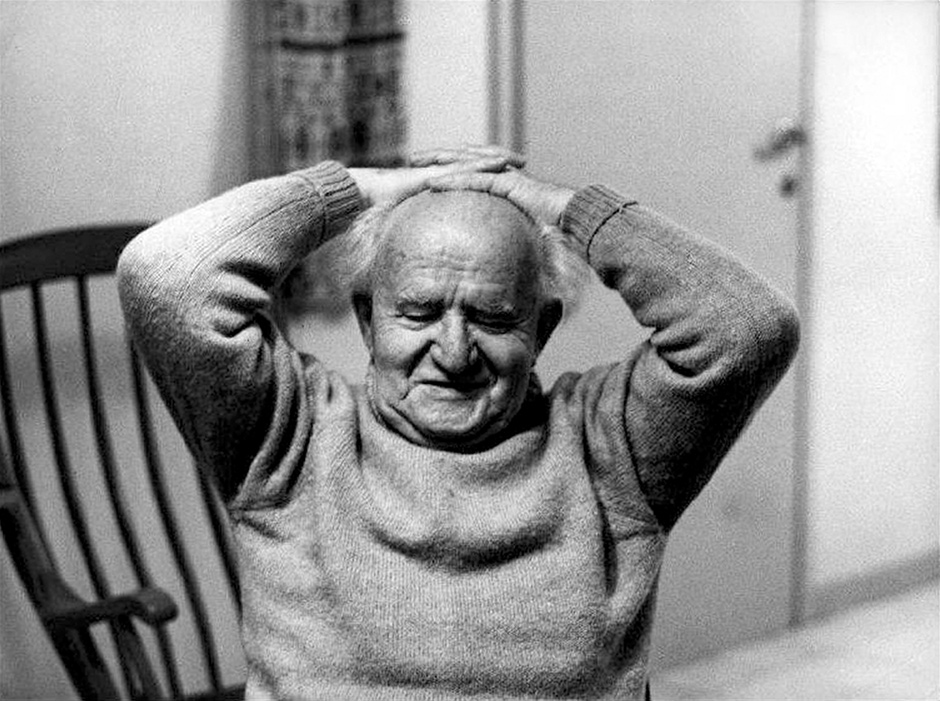

Michael Walzer turned eighty this year, as vital, productive, and intellectually alive as ever. After twenty-eight books, hundreds of articles, decades of teaching at Princeton and Harvard, editing Dissent as a nonsectarian voice of the democratic left, his work remains an essential reference point in academic and public discussion of the most pressing ethical dilemmas in international politics.

You can’t teach a class about just war and the ethics of intervention without using his Just and Unjust Wars (1977); you will not think clearly about whether justice is local and national or universal and cosmopolitan unless you have read his Spheres of Justice (1983); you can’t understand the vexed relationship between religion and politics without pondering The Revolution of the Saints (1965). His work may range widely, but his allegiances have remained stubbornly persistent. He has never wavered in his commitments to a secular, pluralist “democratic left,” to an Israel that makes peace with the Palestinians, and to a social theory that is practical, focused on issues, and rooted in specific historical cases and situations. “I follow the maxim about political life,” he has said, “that nothing is the same as anything else.”

He’s also said, with disarming but false modesty, that “I have always had difficulty sustaining an abstract argument for more than a few sentences.” In fact, his work manages to combine extended abstraction with masterful use of comparative examples. He shies away when called a public intellectual, but he is a genuinely democratic thinker, with a true teacher’s vocation for developing complex and nuanced arguments that he takes care to make as clear as he can. A book by Walzer will always be a pleasure to read, even when you find yourself shaking your head in disagreement.

His latest project, first delivered as lectures at Yale, takes him back to preoccupations that have defined his work for fifty years: why the democratic left condescends to religious conviction; why secular revolutions beget religious counterrevolutions; why in Israel, David Ben-Gurion’s founding vision of a secular civic state, granting equality to Jews and Palestinians alike, is now in retreat before an increasingly intolerant and exclusionist political culture.

While Israel remains the central focus of The Paradox of Liberation, Walzer has made a major contribution to the question of what’s happening there simply by arguing that Israel may not be so special after all: the same kinds of problems may be occurring in other states created by national liberation movements. He compares what happened to Ben-Gurion’s vision with what befell Jawaharlal Nehru’s in India and Ahmed Ben Bella’s in Algeria.

In all three cases, he asks, why did secular liberation movements fall prey, within a generation, to a religious counterrevolution? What does this tell us, he asks in turn, about Zionism, the Indian Congress Party, and the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN)? What was it about religion that these movements failed to understand?

The paradox of liberation, Walzer argues, is that the liberators looked down on the people they came to liberate. None of Kant’s “crooked timber of humanity” for these revolutionaries: they all believed that the timber made crooked by oppression could be planed straight as a board. Liberation was always an ambiguously dual project: to free the people from the colonial power and then to free them from their own submissiveness and psychological subjugation.

The Algerian FLN’s Soummam conference platform of 1956 positively seethes with scorn toward “the torpor, fear, and skepticism” of the Algerian population in general. The revolutionary militants of the FLN vowed that they would shock their people into militant consciousness and awaken “their national dignity” after a century of colonial occupation. If it took bombs and the assassination of collaborators with the French to do this, so be it. Through this trial by fire, Frantz Fanon, the Algerian revolution’s leading theorist, proclaimed, “a new Algerian man” would be born.

The Zionist revolutionaries took a similarly millenarian view of liberation: not just to throw out the colonial oppressors, in this case the British, but to create a new kind of Jew. In 1906, for example, Ze’ev Jabotinsky wrote that Zionism’s “starting point is to take the typical Yid of today and to imagine his diametrical opposite…. Because the Yid is ugly, sickly, and lacks decorum, we shall endow the ideal image of the Hebrew with masculine beauty.” Zionism’s weird streak of anti-Semitism, Walzer allows us to see, flowed directly from its idea of what liberation had to be about. Achieving national independence was not just winning self-government, but using state power to throw off the dead weight of subjection burdening the very soul of the Jewish people.

This took the measure of the harm that the sufferings of exile had done, but at the same time it condescended toward the sustaining beliefs of the Jews the revolutionaries came to free. The roots of this condescension, Walzer argues, lay in a deep misconception about religion. In exile, in the diaspora, the Jewish faith had not always been the willing accomplice of subjection and accommodation, as the Zionists too often seemed to believe: religion had also been a source of resistance and affirmation.

Advertisement

In the Indian revolution, too, religion was dismissed as an obstacle, never truly seen as a potential resource to fuel revolt. Nehru argued that the major challenge of freedom was not just throwing out the British, but liberating the vast mass of the population from the stranglehold of India’s religion and their prevailing “philosophy of submission…to the prevailing social order and to everything that is.” Once religious traditionalism was challenged by a humane, progressive reformist state, Nehru thought, its illusionary comforts would vanish, in his words, “at the touch of reality.”

The other leaders of national liberation movements believed the same, though as Walzer points out, there were nuances. The FLN conceded that a free Algeria would be an Islamic democracy. The Zionists acknowledged, sometimes reluctantly, that their movement’s support among the Jewish masses depended almost entirely on the ancient biblical call, repeated in everyday worship, to remember Jerusalem. Whenever the Zionist leadership forgot the biblical warrant for a return to the Holy Land, as the Zionist leader Theodor Herzl appeared to do when he gave serious consideration to accepting a British proposal to settle the Jews in Uganda, the Jewish masses in the shtetl responded with incredulity and anger. There was only one Zion, the one promised in the Bible.

The secular leaders of national liberation realized they could only succeed if they had support from Islamic, Jewish, and Hindu traditions among the poorest and most desperate of their supporters; yet their accommodation of religion was tactical and condescending rather than sincere. The secular revolutionaries believed that history was a story of modernization and that freedom would inevitably win in a battle with superstition, prejudice, and backwardness. In such a story of progress, religion was a vestigial attachment, “the heart of a heartless world” as Marx so condescendingly put it, a haven bound to crumble in the face of the ruthless forces of global capitalism and the relentless pressures of a modernizing secular state.

In the liberationists’ desire to purge their people of the timorous, abject, accommodating, credulous aspects of their character, they sowed the seeds of their own undoing. There were strengths—endurance, solidarity, and faith—in traditional Islamic culture in prerevolutionary Algeria, just as there was wisdom accumulated in the Jewish experience of the diaspora, just as there was a language of freedom and national pride in Hindu traditional consciousness. For the national liberation movements, Walzer argues, none of these religious traditions seemed useful. Instead, they were seen as obstacles to overcome, dead weights to be thrown off. Once the revolutionaries seized control of the state, they were confident that they could use state power to safely relegate faith to a politically innocuous private sphere, while educating a new post-liberation generation to do without religion altogether.

In essence, the liberators were alienated from the people they came to liberate. They were the privileged children of the empires they sought to overthrow. All of them learned the doctrines of modern society and reform from their colonial oppressors. During their battles against the colonialists, they all sought support for their rebellions from secular intellectuals on the other side. It was as if the inner validation they valued most had to come, oddly enough, from the empires they were seeking to overthrow. Ben Bella prized the decoration he received as a veteran of the French army. It’s hard to know who was more of an Anglophile, Chaim Weizmann, the first president of Israel, or Nehru, India’s first prime minister. Nehru (Harrow, Trinity College, Cambridge, and the Inns of Court) confessed to John Kenneth Galbraith that he was the last Englishman to rule India.

Once these Westernizing revolutionaries seized power, once they took control of the state, Walzer argues, their rule proved to be a painful reckoning with the stubborn force of religious traditionalism. In this reckoning, they were forced to shed many of their liberationist illusions. The deepest one was that a secular, egalitarian citizenship could transcend religious, caste, and tribal divisions.

The Algerian revolutionaries promised a single secular code for all Algerians. By 1981, they had conceded jurisdiction over family matters to sharia law. By the late 1980s an Islamist party was challenging the secular revolution in the name of Islamic democracy. In 1991, faced with this challenge, the regime abolished democracy in order, it said, to save the revolution. Barred from democratic politics, the Islamists then went to war against the regime and it was only after a bloody battle, lasting from 1991 to 1997, that the old revolutionary order prevailed, now more autocratic and reactionary than ever. Their revolution had prevailed but at the price of all the ideals for which the revolution had been fought, and though the Islamists were eventually defeated, Algerian society is now more Islamized than ever.

Advertisement

In Israel, the story is different. Democracy survived and for the Jews who made aliyah, their transformation into Hebrew-speaking Israelis kept alive, at least for them, the Zionist idea that political liberation could also deliver inner transformation. But otherwise, Zionist ideals are in full retreat. In December 1947, Ben-Gurion said:

In our state there will be non-Jews as well, and all of them will be equal citizens, equal in everything without any exception, that is, the state will be their state as well.

Who could honestly say that this promise of equality has been kept in Israel today?

Walzer is not clear about how this failure came about. Being surrounded by unremitting Arab hostility on all sides certainly didn’t help, but that can’t be the whole story. Walzer’s essay lacks a full historical analysis of the decline of the inclusive Zionist ideal. One reason surely is that after the astounding victory in the Six-Day War in 1967, hubris led the victors to ignore Ben-Gurion’s warning that holding on to the newly occupied territories posed “a terrible danger” to the future of the Jewish state. Ben-Gurion, then out of power, was ignored and the pragmatic, secular Zionism that he stood for was steadily displaced by an ever more religious and messianic settler movement for whom the territories were not a dispensable trophy of victory, as Ben-Gurion thought, but the heart and soul of biblical Israel.

Walzer, for his part, essentially fingers the religious fundamentalists, particularly the ultra-Orthodox settlers, those whose first loyalty was to their faith, not to their state or even to Israeli democracy, and whose ultimate allegiance was ethnic, particularistic, exclusionary, and, though Walzer does not use the term, sometimes downright racist. These people have no interest in tolerance for Muslims, secularists, or anyone else, because they do not want them in the state at all. They want a home in their own image, faithful in all particulars to religious law.

The ultra-religious, especially the settlers, are the usual suspects in this debate about what happened to the Zionist dream. It may be that Walzer forces the division between secular Zionists and Orthodox fundamentalists in such a way that he leaves little room for those in between, religious Zionists who live their faith but are committed to defending a pluralist and democratic Israel. Walzer does not give much room in his analysis to people like this, but they exist and they may be the source of what hope there is for reconciliation between politics and religion in Israel.

Turning to India, Walzer tells the same story of an inclusive and egalitarian secular ideal being defeated by religious counterrevolution. He compares Ben-Gurion’s Zionism to Nehru’s vision of a secular civic democracy transcending confessional and caste ties. In post-independence India, Nehru insisted, Muslims must be given “the security and the rights of citizens in a democratic state.” In reality, independence took place against the backdrop of a murderous partition and horrendous communal bloodletting. Gandhi met his death in 1948 at the hands of a Hindu supremacist assassin enraged by his gestures of friendship toward Indian Muslims. Today’s rulers of India, the Hindu nationalist BJP, have governed inclusively, but no one forgets that they are actually the ideological descendants of the Hindu supremacist who killed Gandhi.

These are not the heirs that the makers of the 1947 midnight hour in India could have expected. The members of Nehru’s first Cabinet were committed to containing Hinduism, not elevating it. They were secular reformers determined to confront religious traditionalism head-on. They discovered that support for traditional practices was not only entrenched among the Indian masses but also among the nationalist elites of the Congress Party. These Hindu elites closed ranks against the likes of Rajkumari Amrit Kaur (a graduate of the Sherborne School for Girls and Oxford), the minister of health who wanted to wipe out purdah, child marriage, polygamy, bans on intercaste marriage, and laws of inheritance that discriminated against daughters and wives. All of these practices were abolished by legislation, yet eighty years later many survive in one form or another in India.

B.R. Ambedkar, who had risen through the Indian independence movement from poverty as an untouchable outcast to become the drafter of India’s first constitution, remarked irritably in 1951, “I do not understand why religion should be given [a] vast expansive jurisdiction so as to cover the whole of life.” “What,” he asked pointedly, “are we having this liberty for?” When Hindu members of the Congress Party rose up against Ambedkar’s attempt to control the effects of Hindu religious law, Nehru backed down and Ambedkar quit in disgust.

Here surely is a case where secularists gave in to traditionalists. Yet what exactly is the moral that Walzer wants us to take from his story? Sometimes, as in this case, he suggests that the national liberation movements failed because they gave in too often, while at other times, he argues that they gave in too little. Overall, his conclusion is that “it is the absolutism of secular negation that best accounts for the strength and militancy of the religious revival.” Had the modernizers sought a compromise with religion, he suggests, they might not have provoked the counterrevolution that came a generation later. “Traditionalist worldviews,” he writes, “can’t be negated, abolished, or banned; they have to be engaged.” But the secular modernists did “engage.” Nehru sold out the radical modernizers in his own party, let sharia law stand, and tolerated Hindu customs; Ben-Gurion never took power over marriage and divorce away from the religious authorities. The hard men in the FLN capitulated on sharia within a generation of taking power.

In fact, you could argue—and this is the position taken by Marxist critics like Perry Anderson—that the secular revolutionaries weren’t “absolutist” enough.1 The revolutionaries, in this view, never had the stomach, or even the desire, to take on the holders of traditional power. They deferred far too much to religious authorities, traditional landowners, and privileged castes. Had they been more Jacobin, more ruthless in their attack on tradition, superstition, and privilege, they might have forged an egalitarian civic culture robust enough to keep all three permanently in their proper place.

Instead, in India at least, the Congress Party legislated a purely formal legal equality for citizens, leaving caste and religion intact so as to ensure that the vast electoral power of the masses unleashed by democracy would never threaten the property and privileges of the Indian elites. In the compromise that governed India after 1947, the Indian state was never secular, Anderson argues, since Hinduism was clearly privileged, but Muslims and Christians were accorded full confessional freedom, so that intercommunal violence could be kept to a minimum.

Like Walzer, Anderson sees nationalist parties being dragged under by the “confessional undertow” of the social struggles they unleashed and selling out their original principles, but unlike Walzer, he argues that the nationalist movements sold out, not to religious authority, but to class privilege, and once they did so the classes in charge, in each of these societies, had no difficulty in rallying the demons of faith to defend customary and unequal distributions of power. The problem with this is that Anderson’s explanation reduces faith to an instrumental device in the service of class rule.

Religion is not a reliable servant of the powerful. When religious doctrine contests the very supremacy of the secular state and the legitimacy of its law and secular moral custom, it is a threat to the powerful and a threat to their social order. If anything, the three revolutionary movements—Algerian, Indian, and Israeli—underestimated the radical challenge that religious fundamentalism posed to each.

Then the question becomes, what could the revolutions have done differently? Walzer thinks the revolutionaries were naive to believe in the inevitable triumph of secularism, but they were right to “engage” religion, to seek to enlist or co-opt its authority in the founding of their new states. Yet Walzer fails to ask whether the fundamentalist strains of these traditions—Hindu, Jewish, and Islamic—were ever really willing to “engage” with secular revolution. The fundamentalist strains of these faiths never accepted the supremacy of the secular state in the first place.

Fundamentalists of all faiths have an objection to the epistemology of democracy itself, to the idea that political truth is contestable and is arrived at through public debate. They also have an objection to the fundamental moral norm of democratic debate, that there are no enemies in a free politics, only opponents. For a true fundamentalist, truth is divinely received and when a political opponent denies it, he becomes an enemy, to be dealt with, if necessary, by the sword. These epistemological and moral positions—which make it essentially impossible for radical Islamic fundamentalists to accept democracy—do not feature in Walzer’s discussion, but they may have made it impossible for secular nationalists to find common ground at least with the extreme fundamentalists among their religious opponents.2

To this Walzer would say, what else could the revolutionaries do, but compromise with faith in traditional societies so deeply ordered by religious custom?

What is the moral of this story? One way to read Walzer’s essay, though he does not say this himself, is that the “democratic left,” his secular egalitarian idealists, failed to create a powerful and convincing political culture that would offer what religious faith still offers to those who remain in the tent, i.e., a spiritual home.

Another possible meaning to Walzer’s story is that the relationship between secular revolution and religious counterrevolution is not negative and antithetical, but positive and symbiotic. Secular revolutions may not succeed fully, but to the degree that they do, they make it impossible for religious counterrevolutions to entirely turn back the clock. Where secular revolutions fail, their failures leave nothing behind to restrain the fundamentalist impulses that lead the religious into extremism when they gain power.

This becomes clear if you think about cases that Walzer does not consider—the secular revolutions that failed. In Iran, the failure of the Shah’s autocratically secular modernization prepared the way for the furious intolerance of the Shia revolution. In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood’s failure to govern inclusively when it finally won power can be seen as a consequence not just of its intolerance, but of the failure of every secular leader from Nasser to Mubarak to lay the foundations of a political culture of pluralism and inclusion. Perhaps only in Tunisia is there a remaining hope, in the Middle East, that a constitutional order can emerge in which Islamist and secular parties can compete peacefully for power.

If the story Walzer tells seems to be one of defeat, it needs to be said that, in the cases he cites, the story is not over, indeed is never over. This is because, in fact, the secular revolution initially succeeded, and in doing so, laid down political expectations and a political culture that fundamentalism may not be able to uproot. In Israel, the religious and the secular, the Orthodox and the non-Orthodox believers are still fighting, mostly peacefully, over what kind of society their country should become. In India, Narendra Modi rose to power trafficking in Hindu extremism, but the actual exercise of power has so far forced him to respect Nehru’s legacy of intercommunal accommodation. In Algeria, the revolutionary gerontocracy is aging, and the Islamists are waiting for their time to come. When it does, however, those who still remember the secular revolution’s achievements will not surrender, without a struggle, to Islamic theocracy.

In other words, the successful secular revolutions that overthrew empire have not finished their work, and neither have the religious counterrevolutions that rose to contradict them. Only a pessimist would believe that the ultimate outcome is a foregone conclusion and only a dogmatist would want final, crushing victory for either side.