The nineteenth-century cavalry officer George Armstrong Custer, who was a general at twenty-three and dead at thirty-six, has probably been the subject of more books than any other American, Lincoln excepted. All until now move swiftly through the brilliant feats of arms of the Civil War career that made Custer a national hero to focus instead on his last hours. Every schoolboy used to know that Custer died in 1876 on a hill overlooking the Little Bighorn River in Montana with five companies of the 7th Cavalry dead to a man around him, killed by Sioux and Cheyenne Indians. Only a single cavalry horse was found alive on the field.

Custer was the commander so the failure was his, the result of overconfidence and wrong decisions. He had divided his regiment into four groups before sending them into battle, exposing each to defeat in turn. He issued a promise to support the detachment of his second-in-command, Major Marcus Reno, with “the whole outfit,” but failed to give it any support at all. He did not know where the village was that he was planning to attack, or how big it was. He did not know how to reach the village from the bluffs that lined the eastern bank of the river. He believed in error that the Indians were poised to run, not stand and fight. Custer’s own detachment never crossed or even reached the river, much less the village on the other side. In fact, he never actually attacked the Indians at all. They rode out instead to meet him, sent his soldiers reeling back, pursued them up the spine of a long hill, and finally overwhelmed the desperate remnant in about the time, a Cheyenne war leader said later, that it takes a hungry man to eat his lunch.

When news of the disaster spread by telegraph in early July during a national celebration of the Centennial in Philadelphia, the country could hardly believe it. A century of excuse-making promptly began. Two popular images cast the disaster in a heroic light—a chromolithograph commissioned by Anheuser-Busch that hung over bars throughout the land, and a movie still of Errol Flynn playing Custer in the final scene of They Died with Their Boots On. Both depict Custer as the last man standing, wearing a buckskin jacket, hatless, sword in hand, and surrounded by stacks of dead savages.

The reality, long denied, was very different. In the fighting at the Little Bighorn about 261 soldiers and civilians were killed, including four members of Custer’s own family—two brothers, a brother-in-law, and a nephew. The number of Sioux and Cheyenne killed in the fight was far fewer, on the order of thirty to forty, according to an authoritative study of Indian accounts by the historian Richard Hardorff in his book Hokahey! A Good Day to Die (1999). The disparity, typical of a rout, helps to explain what happened. Custer had lost control of the fight. His men were in disarray, incapable of organized defense, overwhelmed in small groups, the bodies of officers and men scattered along their route of flight “like corn,” according to an officer who explored the scene a day or two later. Custer himself was found dead on the hill, shot in the side and in the left temple. The last of his men had been killed as they ran in panic down toward the river, probably hoping to hide in the brush and undergrowth along the bank.

That is roughly the way I think things unfolded, but it is only fair to say that just about everything I’ve said is in dispute by somebody, and sometimes by whole platoons of students of the battle, most of whom want to exonerate Custer, or at least include others in the blame. The record has grown so large that it requires a big chunk of a book just to introduce the leading characters, explain why Washington wanted and forced the war, sketch in the map of the five-mile-long battlefield, outline the chronology of the fight, and identify the many points in dispute before retelling the story of the fatal day and hazarding some new interpretation that is certain to meet a storm of contradiction.

Some very good books about Custer have followed this pattern, but Custer’s Trials, T.J. Stiles’s important and original new life of the general, does not. He seems to have gazed into the dark swamp of the controversy and concluded that nothing new could be learned from revisiting old ground. So he did not, and decided to leave out the battle. The body of his text ends as abruptly as a cliff with Custer marching out of Fort Abraham Lincoln in Dakota Territory at the head of the 7th Cavalry, while the regimental band played “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” All twelve companies of the 7th were under his command for the first time, and they were going out to whip the Indians. This is the point where most books about Custer really get underway.

Advertisement

Leaving the Little Bighorn out of Custer’s Trials is about the boldest purely literary decision I’ve seen in a long while, and the effect is startling. We are given a cursory sketch of the disaster in the twenty-page epilogue that concludes the book, but it would be stretching things even to call it a bare outline. Faintly visible within the epilogue are one or two hints, no more, of where Stiles thinks that things went wrong and who ought to be held accountable. His stony refusal to wrestle with the main event seems willful and strange, and it leaves a reader wondering what is to be gained by tackling Stiles’s substantial book.

Ignore those doubts. He is an accomplished biographer (Jesse James and Cornelius Vanderbilt, which won a Pulitzer Prize); and he has a deep understanding of nineteenth-century American politics, business, and military history of the Civil War era. Custer’s Trials offers ample reward for anyone interested in Custer, in the way golden lives run off the rails, in how large events can be prompted by small persistent flaws of character, or in the way a writer in command of his material can force a reader to take a fresh look at an old subject as buried in stale argument as a fossil embedded in rock. Stiles does not spell out his strategy but it is clear. To understand what Custer did on the fatal day, he believes, we must know who Custer was.

About Custer’s life before he entered West Point in 1857 Stiles tells us little, but at that point the future general springs into the full light of history, pretty much as he remained until the end—a nice-looking, high-spirited fellow, eager to make an impression, obsessed with women, full of confidence, addicted to practical jokes, lazy in his studies, a truster in his luck, poised with one foot on solid ground and one over the abyss. He ignored rules. He racked up demerits at West Point but always squeaked by. In his final year Custer and some thirty other cadets flunked a crucial exam, and all were dismissed. Only Custer was reinstated. Why? He chalked it up to “Custer luck,” and it’s not a bad explanation. On some people—Winston Churchill, for example, who skirted death a score of times—Providence shines. Custer’s luck saved him again when he was court-martialed for permitting one cadet to strike another. That was unforgivable, unless you were Custer. The court only reprimanded him and he was allowed to graduate, last in his class of thirty-four, a few weeks after the Civil War began with the attack on Fort Sumter. People liked Custer; they noticed him and indulged him but nobody expected much from him.

During the first confusing weeks of the war, events tossed Custer one way and another. On his arrival in Washington from West Point a chance introduction to Winfield Scott, the general in chief of the Union Army, resulted in Custer being sent with a dispatch to General Irwin McDowell across the District line in Virginia, where he was preparing to attack the Confederate Army the next day near a winding stream called Bull Run. Custer was in the fight, was shot at but survived, and thereafter peppered family and friends with long letters full of dramatic detail that placed him at the center of events. He wasn’t making things up, just self-absorbed, and always excited most by whatever was happening to him.

Custer’s luck came in two forms—the first was to be noticed and then favored by powerful men. Scott led to McDowell, and thence to McDowell’s replacement as commander of the Army of the Potomac, General George B. McClellan, who put Custer on his staff, where he received a crash course in the politics of war. McDowell was a model general who did everything with energy except fight. But Custer himself saw plenty of action, was always favorably noticed, and on the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg was promoted from first lieutenant to brigadier general—five ranks in one jump!—and put in command of the Michigan Brigade at the age of twenty-three. A few days later a classic cavalry charge by Custer at the head of his men—“Come on, you Wolverines!”—routed a detachment of Confederate cavalry under General J.E.B. Stuart.

Advertisement

Stiles has a talent for describing military action, not just the clash of arms but the setting, the mood of the contending forces, and the meaning of the result. His account of Custer’s feat on the third day at Gettysburg is soberly persuasive and yet full of awe at the miracle of it. In the battle generally considered the turning point of the Civil War, on the very part of the field that helped to decide the battle, Custer in his first week as a general whipped one of the greatest cavalry commanders in history.

That episode pretty well captures the tenor of Custer’s Civil War. He was in a full roster of significant fights—Antietam, Trevilian Station, the Battle of the Wilderness, Third Winchester, where he helped win the victory that secured Lincoln’s reelection in November 1864, Cedar Creek, and the final weeks of chasing down Robert E. Lee and the remnant of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House. Custer inspired confidence equally in the generals above him and the men who followed him. “So brave a man I never saw,” a major in the Michigan cavalry wrote home after the Battle of Gettysburg. “Under him our men can achieve wonders.” Custer was wounded lightly a couple of times, nothing worse. Once or twice he attacked foes who were too many or too tough, but luck always got him out again.

Custer could ride, was a good shot, and was brave to a fault, but so were a lot of other young cavalry officers, especially in the armies of the South. Custer’s gift that mattered most was something like an athlete’s instinct for the unfolding of play in a heated game. On a battlefield he knew where everybody was, where they were going, where they were weak or off-balance, what they were trying to do, what they weren’t expecting. Custer was what the noted military writer S.L.A. Marshall, speaking of the Oglala Lakota chief Crazy Horse, called a “battlefield plunger.”

It was Custer’s luck of the first kind that put him in command of the Michigan Brigade at the right moment, and it was Custer’s luck of the second kind that let him survive not just Gettysburg but a dozen other fights where a chance bullet or the sniffles followed by pneumonia might have ended his life. That and an unmarked grave were the common end of thousands of promising lives. But Custer was fortune’s child, generals depended on him, he was noticed and celebrated. He married the prettiest girl in Monroe, Michigan, and he stole the show at the Grand Review celebrating victory in Washington a month after the war when his horse, spooked by a garland of flowers tossed to the boy general, tried to throw him but failed while thousands watched. You can’t overwrite the dazzling arc of Custer’s war, but his career after the war was a different matter.

The first and bitterest sting was being dropped back into his rank in the regular army, which was captain. Friends in high places soon got him a position as lieutenant colonel in a new regiment of cavalry, the 7th. Technically Custer was second in command but most of the time the regiment’s colonel was on leave or on detached duty. Pieces of the 7th under Custer were sent here and there after the war, to maintain civil peace during Reconstruction in Texas and Kentucky, and to secure the Kansas frontier from Indian attack. “The 7th Cavalry,” Stiles dryly notes, “would serve as a complete unit only once in Custer’s lifetime, with disastrous results.”

The second half of Custer’s Trials lavishes narrative attention on three connected stories—Custer’s sometimes stormy relationship with his wife Elizabeth, called Libbie, who wrote three remarkable memoirs of her life with “the General”; Custer’s education in fighting Indians, which involved much floundering at the outset; and Custer’s addiction to risk, which made him bold in war and reckless in peacetime in the pursuit of fortune at cards or in business. No one has dug more deeply, or with better literary effect, into the Custer record than Stiles, always excepting the final battle. He has read about that, too, of course, but not with the same focused passion for mastery. From Custer’s half-mad desire to dazzle the world and Libbie, and from his way with war, Indians, and risk, Stiles has coaxed forth the patterns of character that help to explain how the man who whipped Stuart at Gettysburg was annihilated by the Lakota and Cheyenne at the Little Bighorn. Explaining that is ultimately the point of going to so much effort, but Stiles has another goal: to explain how Custer fit comfortably into the post–Civil War world of American striving and acquisition.

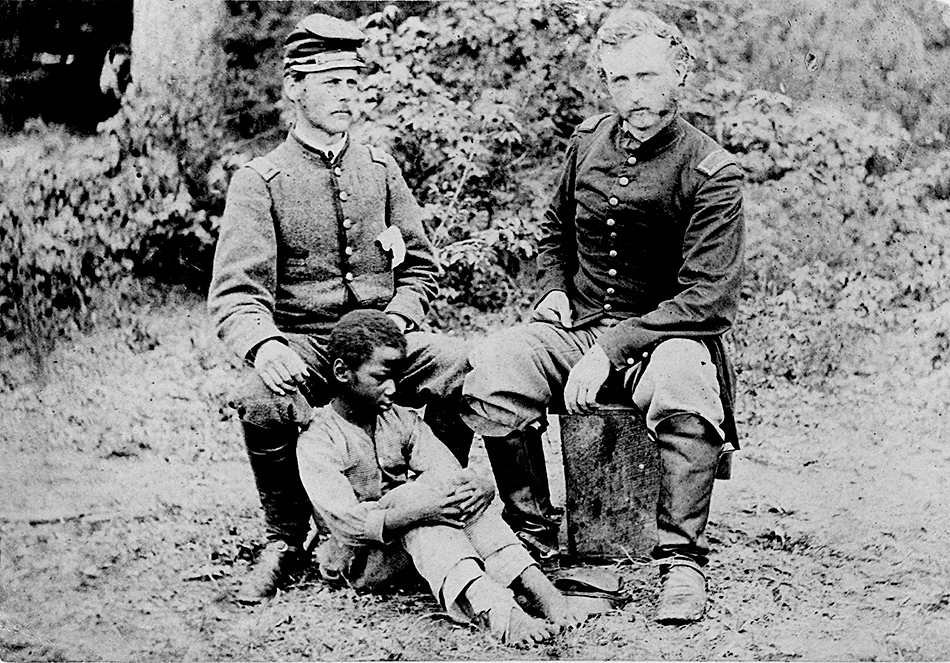

Custer established his reputation as an Indian fighter with an attack on a village of Cheyenne on the Washita River in Oklahoma in November 1868. Behind the attack were the usual causes—Indian reluctance to remain on a reservation where there was never enough to eat, raids by young warriors on settlements, a storm of angry editorials from western newspapers, stern warnings from agents and military officers. Placed in command for the campaign by one of his old mentors, General Philip Sheridan, Custer drove his men until scouts reported discovery of a winter camp of hostile Indians along the Washita. He followed the textbook and attacked at first light. The official tally was 103 dead Indians; 875 dead horses, shot on Custer’s order; and the burning of fifty lodges with all their stores for winter—in short, a mighty victory soon celebrated by Harper’s Weekly with a double-page engraving of officers and men of the 7th charging with revolvers blazing. In a moment Custer had regained his place as a national hero.

But a counternarrative soon developed. Some said (now many say) that Custer had attacked the wrong Indians, a village under one of the Cheyenne peace chiefs, Black Kettle. In the wild melee women and children were shot down along with the men. But the sharpest criticism centered on the fate of Major Joel Elliott, who had charged upriver in mid-battle with nineteen men after some fleeing warriors. Soon after, another officer of the 7th, Lieutenant Edward Godfrey, discovered, when he had a chance to look from a rise, that the river was lined with Indian lodges as far as he could see. Without knowing it Custer had attacked a huge winter camp, a thousand lodges in all.

Godfrey hurried back with the news. Custer did not linger to learn the fate of Elliott and his men, but departed briskly as soon as the 7th had finished its job of destruction. Two weeks later the bodies of Elliott and his men were found naked, shot up and bristling with arrows. One of Major Elliott’s close friends in the 7th, Captain Frederick Benteen, grasped the bitter truth immediately—the general had simply abandoned the major to his fate. But in retelling this episode Stiles is quicker to fault Benteen, the officer who likened the dead at the Little Bighorn to scattered corn, than Custer. “If disharmony in the 7th Cavalry began with anyone,” he writes, “it was with Captain Benteen, a soft-faced but bitter man…. He hated Custer immediately.” Well, the reader is inclined to ask, why not?

Stiles gives us a final insight into Custer’s state of mind in the months before he rode off to whip the Indians in Montana. The proper word for it might be despair, or perhaps desperation. This emerges in a brief but lucid account of Custer’s “business life,” which amounted to reckless financial speculation in New York City, where he lived for two long periods. Of business he knew nothing. An initial effort to promote the notional “Stevens Lode Silver Mine” west of Denver went nowhere. The idea was to issue stock and run up the shares with publicity and rumors until the “owners,” Custer and a handful of plutocrats who “bought” shares at a fraction of par, could sell out and let the buyers shift for themselves. It might have worked if someone had paid attention to the mine itself, but no one did.

A second bid for riches ended more badly still when Custer in New York in late 1875 tried to make a fortune on the stock market through short-selling. He had no feel for markets and no access to genuine insiders. His guesses tended to be wrong. Trades totaling $398,983 left him $8,578 in debt, a stupendous sum for a light colonel in the army. “It was larger than the annual salaries of major railroad presidents,” writes Stiles. In February 1876 Custer issued an IOU for the whole of his losses at 7 percent interest, with a promise to pay in six months—August 1876. Libbie made no mention of these troubles in her memoirs, and probably had only a faint understanding of the situation.

To get out of this mess would require a miracle of the sort that saved Custer time and again during the war. Now he was thirty-five, he was dead broke (if the accounting was honest), chance of promotion in the post–Civil War Army was slim to zero, and he had half a year to brood upon the size of the miracle he would need to pay that note when it fell due. Facing all that, roughly, is where Stiles leaves him—Custer with the bloom off, riding out at the head of a regiment of cavalry to see if a rousing victory over the Indians could deliver a miracle.

Custer’s personal story ends with shocking completeness as he disappears downriver with his detachment a little after noon on the fatal day. If Stiles wished to argue (as many have) that responsibility for the disaster falls wholly or partly on someone else, there is much he might have said, but if he believes, as his book implicitly argues, that the disaster was Custer’s doing, there is no need to press further. It is this clarity of judgment that sets Stiles’s book apart from all others. He sticks to the life, in effect telling the reader that Custer was the cause—the man brought it on himself.

But then in the epilogue something odd happens. Stiles betrays a certain softening, a holding back, a hint of readiness to offer excuses. The wavering emerges from his account of the proceedings of a court of inquiry into the battle held in 1879. Its purpose was to weigh the behavior of Major Reno, Custer’s second-in-command, whom many had accused of cowardice. In the course of the inquiry attention was focused as well on Captain Benteen, to whom Stiles has taken a sharp dislike, singling him out as an unreliable narrator—a probable liar, in fact. The dislike is almost visceral, the way two men at a party with only a word or two might be on the verge of a fistfight. Benteen’s testimony at the Reno court of inquiry, Stiles writes,

established one thing for certain: it is possible to sneer continuously for days at a time. He appeared in the full flower of his petty arrogance, steeped in an embittered subordinate’s nitpicking resentfulness and a pervasive disdain for Custer.

Where does this vehemence come from? Why is Stiles expressing it now?

The inquiry established that the first phase of the battle, an attack on the southern end of a huge Indian village by Reno with about 110 men, ended with his retreat to a hilltop back across the river where he was joined by Benteen with a detachment of similar size. Custer meanwhile had disappeared downriver with five companies of the 7th, about 210 men, after promising to support Reno’s attack with “the whole outfit.” A principal question at the inquiry was whether Reno, as the senior officer on the hilltop, and for that matter Benteen, too, could have and should have known that Custer, far from able to support Reno with “the whole outfit,” was in desperate straits himself.

This is not a question that can be answered with a simple yes or no. But Stiles without further argument reaches a harsh judgment. “It is striking,” he writes,

that Benteen, who loathed Custer for purportedly abandoning Maj. Joel Elliott and nineteen men at the Washita, should so lightly excuse his own abandonment of ten times as many troops. Could his and Reno’s combined battalions have reached Custer, let alone rescued him? No one can ever know. What is certain is that they never tried.

This turns facts on their head. Reno and Benteen did not abandon Custer. They were pretty sure, in fact, that he had abandoned them, just as he had Elliott. But Stiles is harsh; he is saying that Reno and Benteen should have tried to rescue Custer, which must mean they are at fault for not trying, which in effect says the blame must be at least partly theirs. With this stinging judgment Stiles has plunged his book into the thick of the old arguments. All come from the impulse to defend Custer, to avoid saying plainly what was obvious from the first day: that he picked a fight he could not win.

But it would be pointless to go on. Stiles has already refused this quarrel. His final judgment raises questions he has made no serious effort to address, much less answer. I can offer only one explanation for this last-minute change of heart: Custer had a way about him and by the time Stiles reached his final pages, he had fallen under the general’s spell. This leaves us with a split judgment. If you want to understand the battle you will have to look elsewhere. But if you want to understand how Custer’s character became his fate, then Stiles’s book is the one to read before any other.