Although Alexander Hamilton never became president of the United States, he is more famous than most presidents, and these days is doubly famous because of the impending decision to remove him from the ten-dollar bill and, more important, because of the hit Broadway show Hamilton. Indeed, the response to this musical has been phenomenal: it is sold out for months.

Both the left and the right like this play; President Obama, who took his daughters to see it, said that he was “pretty sure this is the only thing that Dick Cheney and I have agreed on—during my entire political career.” It’s patriotic without being self-righteous or stuffy. So excited have people become with this musical treatment of the rise and fall of our first secretary of the treasury that the Rockefeller Foundation and the producers have agreed to finance a program to bring 20,000 New York City eleventh-graders to see Hamilton at a series of matinees beginning next spring and running through 2017. Using a curriculum put together by the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, they plan on drawing the students largely from schools that have a high percentage of low-income families.

No one thought of doing this for Jesus Christ Superstar, Les Misérables, or even 1776, which dealt with America’s writing of the Declaration of Independence. This show is different. Not only is it sung in the stylized rhythmic and rhyming manner of rap and hip-hop, but perhaps more important, the cast is deliberately composed almost entirely of African-Americans and Latinos. This symbolizes as nothing else could that the history of the founding of the United States belongs to all Americans at all times and in all places and not simply to elite white Anglo-Saxon males who lived in the eighteenth century.

Since we Americans have no common race or ethnicity, the main things that hold us together and make us a nation are the ideals of liberty, equality, and democracy that came out of the Revolution, the most important event in American history, in which Hamilton was a major participant. Americans have been desperate to attach all immigrants and all minorities to the history and meaning of the US, and this play helps to do that. It is no wonder that it has been so passionately and universally celebrated.

The show is the creation of Lin-Manuel Miranda, the very talented composer, lyricist, and star of Hamilton, and evidently a man with a thousand show tunes in his head. When Miranda read Ron Chernow’s 2004 biography of Hamilton, he was reminded of his father’s immigrant life. Just as Hamilton had been born in Nevis in the British West Indies in 1755 and moved to New York in his late teens, so Miranda’s father moved from Puerto Rico to New York at age eighteen. Miranda saw in Hamilton’s tumultuous life the risky and reckless immigrant story of America. His Hamilton announces himself early in the show: “Hey yo, I’m just like my country,/I’m young, scrappy and hungry,/and I’m not throwing away my shot!”

But the actual opening lines belong to Hamilton’s personal nemesis Aaron Burr, who had to be the other major character in the show; for the entwined lives of Burr and Hamilton are the central drama of the play. Burr poses the crucial thematic question: “How does a bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a/Scotsman, dropped in the middle of a forgotten/spot in the Caribbean by providence,/impoverished, in squalor,/grow up to be a hero and a scholar?” Miranda has Hamilton’s close friend John Laurens give the answer. “The ten-dollar founding father without a father/got a lot farther by working a lot harder,/by being a lot smarter,/by being a self-starter.” Then Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, George Washington, and Hamilton’s wife Eliza chime in with a succinct rhyming narrative of Hamilton’s early years. Chernow has said that this opening song, less than five minutes long, “accurately distills” the first forty pages of his book.

Some people like history less distilled, and a recent book, John Sedgwick’s War of Two: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Duel That Stunned the Nation, tells at length the same story as Miranda’s play. Sedgwick is a descendant of Theodore Sedgwick, a political leader in the early Republic who was a friend to both Hamilton and Burr. Like Miranda, Sedgwick wants to bring these eighteenth-century characters in knee britches down to earth. He has not sought out new information about Hamilton and Burr, but instead has tried “to make sense of the mountains of existing material.” He pays special tribute to Chernow’s biography of Hamilton and to Milton Lomask’s two-volume life of Burr, and especially to Gore Vidal’s novel Burr for doing “more to evoke the humanity of our all-too-revered Founders than a library of factual accounts.” Vidal, he says, “inspired me to consider Hamilton and Burr as if I’d heard them gripe about money or squabble with their wives, or smelled their cologne.”

Advertisement

The history of the intertwined lives of Hamilton and Burr is so improbable, so dramatic, and so tragic that no novelist could get away with making it up. Although Sedgwick is a novelist as well as a nonfiction writer, he has sought in this book to write only history, which is enlivened, however, by his novelistic talents.

Comparing Sedgwick’s four-hundred-plus-page book with Miranda’s play is difficult and unfair. Sedgwick’s War of Two, like Chernow’s great biography, has depths and details that the musical cannot match, however accurate it is in depicting the outlines of Hamilton’s life. Of course, Sedgwick’s book will never have the impact on the public that Miranda’s play is having. The show moves and electrifies from start to finish, with several show-stopping numbers, especially the ones sung by George III. No history book can do that.

Because Hamilton’s father, James Hamilton, the younger son of a Scottish laird who had come to the Caribbean to make his fortune as a merchant, and his mother, Rachael Lavien, were not legally married, Hamilton’s birth was illegitimate, a stain his enemies never let him forget. Miranda portrays Hamilton accurately as an amazingly bright, sensitive, and ambitious man with a chip on his shoulder. After his father abandoned the family in 1765 and his mother died in 1768, the fourteen-year-old orphan got a clerical job in a trading firm in St. Croix and went on, in effect, to run it, all the while yearning for a war in order to escape from what he described as his “groveling condition of a clerk…to which my fortune, etc. condemns me.” Sent to New York for an education by generous patrons, who were impressed by an account of a hurricane that the young clerk had written in a newspaper, Hamilton never looked back. Miranda has his Hamilton put it this way: “There’s a million things I haven’t done,/but just you wait, just you wait…”

In many ways Hamilton and Burr were very much alike. They were born a year apart, with Burr the younger. They were both orphaned as young boys and resembled each other physically. Both were slight and short, with Hamilton about five-seven and Burr perhaps an inch shorter. Both had sharp and quick minds and both became first-rate lawyers. Both had courage and sought out military action. Both were articulate and personally magnetic, “born leaders,” says Sedgwick. Despite their slender builds they tended to dominate a room. They were especially attractive to women, and they devoted a great deal of attention to them.

For Miranda the three Schuyler sisters, one of whom Hamilton married, stand in for scores of other women, at least as far as Burr is concerned. Sedgwick calls Burr “an unabashed sexual enthusiast” who “enjoyed the close companionship of dozens if not hundreds of women, all of them willing if not enthusiastic.” In the eyes of his enemies Hamilton was not much different. John Adams said that Hamilton possessed “a superabundance of secretions which he could not find whores enough to draw off.” And as both Sedgwick and Miranda emphasize, Martha Washington named her frisky tomcat Hamilton.

Despite the obvious similarities between the two men, however, the contrasts were even greater. Burr may have been an orphan like Hamilton, but his background could not have been more different. He was the son of the president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) and the grandson of the great Puritan divine Jonathan Edwards. Unlike all the major founders—Jefferson, Washington, Adams, Madison, Franklin, and Hamilton—who if they attended college were the first in their families to do so, Burr was born fully and indisputably into whatever aristocracy eighteenth-century America possessed.

Burr took his aristocratic status for granted and never felt he had to earn it. Lacking as they did any distinguished ancestry, Hamilton and the other revolutionary leaders constantly celebrated classical virtue, that is, the sacrifice of one’s private interests for the sake of the public good, as the only proper source of a republican elite. By contrast, Burr had no need to talk of virtue, and seems to have had no other interest but his own. He was certainly never accused of hypocrisy.

In rhyme after rhyme Miranda generally portrays the two men pretty much the same way as Sedgewick does. He has the cool and crafty Burr offering advice to the intense and loquacious Hamilton: “Talk less…smile more…. Don’t let them know what you’re against or what you’re for.” When Hamilton expresses surprise at this remark, Burr asks, “You wanna get ahead?” Then remember that “fools who run their mouths off wind up dead.”

Advertisement

But occasionally Miranda is harsher on Burr than Sedgwick is, especially in the way he depicts Burr’s treatment of women. He has Burr say to Angelica Schuyler, “Excuse me, miss, I know it’s not funny/But your perfume smells like your daddy’s got money.” When Angelica replies, “Burr, you disgust me,” he responds, “Ah, so you’ve discussed me./I’m a trust fund, baby, you can trust me!” Actually, it was Hamilton who looked at marriage as a means to wealth. “As to fortune,” he said in outlining the qualities of a future wife, “the larger stock of that the better.” Eliza Schuyler, the daughter of the wealthy New York patroon Philip Schuyler, fit the bill.

By contrast, Burr waited for a woman named Theodosia, who was ten years his senior, married to a British officer, and the mother of five children. Fortunately for Burr, the British officer died in Jamaica, and Burr married Theodosia not for her wealth but for her “cultivated mind.” Burr was far more charming with women than Miranda depicts in the exchange with Angelica. Indeed, what redeems Burr in many modern eyes was his admiration for Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and his faith in feminism. “Burr,” writes Sedgwick, “held to the heretical belief, shared only by John Adams in the circle of Founding Fathers, that women were fully the equals of men, just as capable in intellect, just as sensible, and just as deep in feeling.” Yet Sedgwick admits that despite Burr’s extraordinary success with women, he was ultimately “indifferent to them.”

When the Revolutionary War began both Hamilton and Burr read up on soldiering and joined as glory-seeking youngsters. As college graduates, both became officers. Burr was involved in General Richard Montgomery’s ill-fated attack on Quebec in 1775 and handled himself well. Hamilton began as an artillery officer, but his obvious talents led General Washington to appoint him as his aide-de-camp. Washington tended to treat him as a son, which Hamilton resisted. “Don’t call me son,” Miranda has him saying over and over. Burr too was appointed to Washington’s staff, but that lasted just ten days. “Ever after,” says Sedgwick, “Washington dismissed Burr as an ‘intriguer’ and never again welcomed him into his inner circle.” Something about Burr grated on Washington—Miranda suggests Burr’s presumptuousness and lack of deference. Miranda has Washington welcoming Hamilton just as he dismisses Burr, telling him, “Close the door on your way out.”

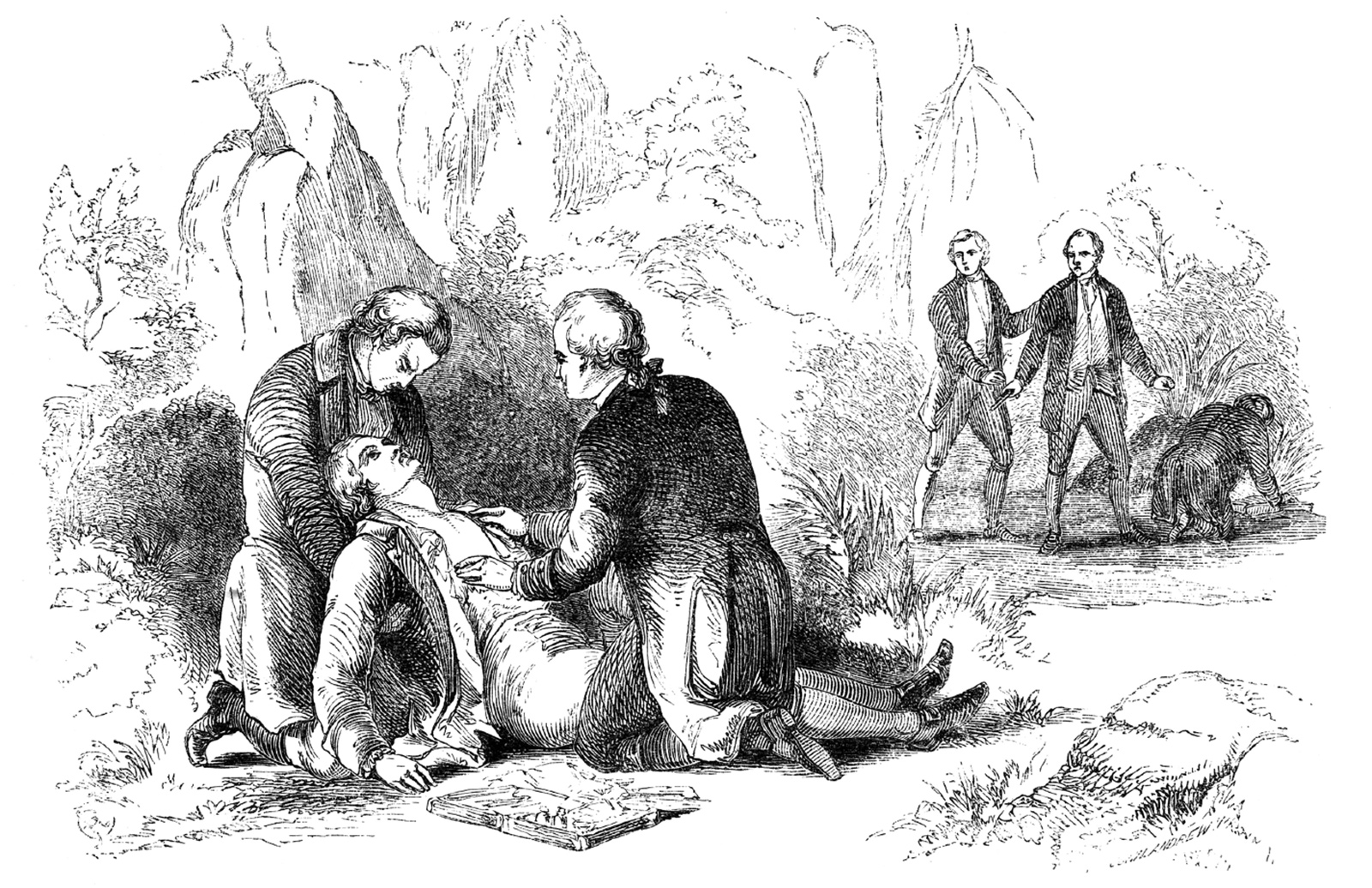

Both men were at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778 where Washington castigated General Charles Lee for disobeying orders. Following his suspension as a result of a court-martial, Lee criticized Washington in print, which prompted John Laurens to challenge him to a duel. Hamilton served as Laurens’s second. Since Burr’s antipathy to Washington made him sympathetic to Lee, Miranda exercises poetic license and has Burr present at the duel, suggesting that he was Lee’s second.

Miranda uses this occasion to spell out in song the rules of dueling, which was quite common in the Revolutionary era, especially between military officers. Although it was one of the ritualized ways in which gentlemen defended their honor, it did not usually end in anyone’s death. Hamilton engaged in eleven duels, but exchanged fire only in his fatal one with Burr. Monmouth was Burr’s last action, and a year later, piqued at the way he had been treated by Washington, he resigned his commission.

Hamilton pestered Washington for a field command, and finally at Yorktown in the fall of 1781 the commander-in-chief yielded and gave him command of a New York light infantry battalion. Lieutenant Colonel Hamilton led his men on a successful bayonet attack on a British redoubt, throwing himself first over the parapet. Miranda exaggerates Hamilton’s role at Yorktown. He has Lafayette telling Washington that we have the guns and ships and can cut the British off at sea, “but/for this to succeed, there’s something else/we need.” Washington says, “I know.” And Washington and the whole company cry out “Hamilton!” “Sir,” says Lafayette, “he knows what to do in a trench./Ingenuitive and fluent in French.” Miranda implausibly suggests that Hamilton all by himself turned the tide of the battle.

After the British surrender at Yorktown, the war eventually came to an end. Lafayette returned to France and Hamilton returned to his wife Eliza and family and joined Burr in New York City as an attorney. According to a contemporary New York lawyer, the two attorneys became “the two greatest men in the state, perhaps the nation.” Their speaking styles were very different. Burr’s, writes Sedgwick, was “always conversational—personal and colloquial. Hamilton’s was oratorical—universal and timeless, if occasionally rather dense.” Miranda echoes this view. He has Hamilton say to Burr, “I know I talk too much, I’m abrasive./You’re incredible in court. You’re succinct, persuasive.”

In the mid-1780s both men became representatives in the New York assembly. Burr tended to see his participation in politics as a means of enhancing his income, for he was overspending on his house, furnishings, clothes, and wine, and deeply in debt. Although serving in the state legislature, Hamilton was less interested in New York than he was in the fate of the national government. In 1787 he became one of the New York delegates to the convention that created the Constitution. While Hamilton wrote a majority of the Federalist papers on behalf of the Constitution, Burr took no position on the document and didn’t seem to care about such matters. Miranda has Burr sing, “I’ll keep all my plans close to my chest./I’ll wait here and see which the wind will blow./I’m taking my time, watching the/afterbirth of a nation,/watching the tension grow.”

With the establishment of the new national government in 1789 and the appointment of Hamilton as secretary of the treasury and Jefferson as secretary of state, Hamilton’s principal antagonist temporarily shifts from Burr to the Virginian, who had returned from serving as minister to France. Once Jefferson and Madison grasped the significance of Hamilton’s financial program, with its assumption of the states’ debts and its creation of a national bank, they went into opposition and began organizing the Republican Party. Miranda handles all of this with colorful rhyming exchanges. He has Jefferson saying to Hamilton, “In Virginia we plant seeds in the ground./We create. You just wanna move our money around.” Hamilton responds, “Thomas. That was a real nice declaration./Welcome to the present, we’re running a real nation./Would you like to join us, or stay mellow,/Doin’ whatever the hell it is you do in Monticello?” Then he adds, “Yeah, keep ranting,/we know who’s really doing the planting.”

Burr avoided taking positions on any of these crucial issues. He mentioned Hamilton’s plans for a national bank at one point in 1791 but confessed that he did not have time to read them. He always kept his political options open and said little about them. Puzzled by Hamilton’s candor, Burr asked, according to Miranda, “Why do you always say what you believe?”

The issue that turned Hamilton’s dislike of Burr into “savage contempt” occurred in 1791. Hamilton assumed that his father-in-law, Philip Schuyler, would be reelected to the US Senate, but Burr used his support in the New York legislature, which did the electing, to have himself elected senator. With the emergence of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties in the 1790s, Burr, the man with no principles, could have gone either way, but since Schuyler was a Federalist Burr necessarily became a Democratic-Republican. Miranda has Hamilton asking Burr in the aftermath of his Senate victory, “Since when are you a Democratic-Republican?” Burr replies, “Since being one put me on the up and up again,” to which Hamilton responds, “No one knows who you are or what you do.”

But perhaps more important to Miranda’s play than politics are the personal relationships between Hamilton and the Schuyler sisters, Eliza (his wife) and Angelica, and his affair with Maria Reynolds. There was Hamilton, “Longing for Angelica./Missing my wife./That’s when Miss Maria Reynolds walked into my life.” Hamilton’s affair began in 1791 when Mrs. Reynolds played on his sympathy and claimed to be an abused wife. Actually, she and her husband concocted a scheme to blackmail Hamilton, and rather than have his adultery exposed, he paid. Rumors that Hamilton might be misusing treasury funds led some congressional figures in 1792 to investigate, but when Hamilton explained the circumstances of the affair and the reason for paying Mr. Reynolds, the investigators dismissed his liaison with Maria Reynolds as a private matter.

Five years later, however, it all became public. The unscrupulous journalist James Thomson Callender charged that Hamilton’s relationship with Mr. and Mrs. Reynolds involved speculating with treasury funds. In order to defend his reputation for public virtue, Hamilton published a lengthy pamphlet laying out all the sordid details of the affair with Maria Reynolds. Even though the revelation deeply hurt his wife Eliza (for whom Miranda has written a touching ballad), Hamilton believed that it would be better to be thought a private adulterer than a corrupt public official. The publication was a disastrous mistake, and Hamilton never really recovered from it.

By attacking his fellow Federalist John Adams in another pamphlet, Hamilton contributed to the Democratic-Republican Party winning the election of 1800. Unfortunately, however, Jefferson and Burr received an equal number of electoral votes for the presidency. Although everyone knew that Jefferson was supposed to be the president and Burr the vice-president, the Democratic-Republican electors forgot to withhold one of their votes for Burr. Under the Constitution as then written a tie in electoral votes threw the decision into the House of Representatives. Suddenly there arose the possibility that the Federalists in Congress could engineer the election of Aaron Burr as president. Although many Federalists, including John Marshall, wanted to do just that, saying that Burr was an opportunist and someone they could deal with (“grab a beer with,” says Miranda), Hamilton thought otherwise. As the likelihood of a constitutional crisis emerged, Hamilton wrote letter after letter to his fellow Federalists, urging them to support Jefferson and not Burr as president. Although he hated Jefferson more than any other political figure, Jefferson, he said, at least had pretensions to character; Burr had none.

Finally, after thirty-five ballots, the Federalists in Congress allowed Jefferson to become president. Throughout the entire crisis Burr said nothing publicly to discourage the Federalist maneuvering, and thus he destroyed his future in the Jeffersonian Republican Party.

To keep his play within three hours Miranda had to compress and collapse some events. He makes Hamilton’s behavior in this election the source of the duel, when in fact Burr called Hamilton out in the aftermath of Burr’s failed attempt in 1804 to become governor of New York. Hamilton was not eager for a duel. His nineteen-year-old son Philip had recently been killed in one; but his acute sense of honor led him to his death. Burr was stunned by the public reaction to his killing of Hamilton, and he spent the rest of his life desperately trying to recover his reputation.

It’s a great story and both the musical and the book make the most of it. No doubt Miranda’s play cannot match the details of Sedgwick’s lengthy book. But he does manage to hit all the main points in the relationship between the two men. Of course Miranda had to move some people and things around and exercise some artistic license to fit some events together. But he doesn’t seem to make any unintentional mistakes.

The same cannot be said for Sedgwick’s history book; it’s full of minor errors. He has Benjamin Franklin in Paris negotiating the peace with Britain all by himself. He mistakenly makes John Adams the minister to France when in fact Adams was never minister and was only a member of a peace commission. He says that President Washington pardoned the rebels in Shays’ Rebellion when in fact it was Massachusetts Governor John Hancock. He has Washington selecting Hamilton to make a “grand summation” of the deliberations of the Constitutional Convention “at the end” of the meeting, when actually Hamilton gave his six-hour speech on June 18 near the beginning, and it was not a summation at all but an effort to make the Virginia plan seem more moderate. He says the Senate decided to call the chief executive the president, when actually it was the House of Representatives that overturned the more monarchical title suggested by the Senate. These are small matters perhaps, but cumulatively they tend to undermine confidence in the author’s command of the period.

In the end, however, neither Miranda’s sparkling show nor Sedgwick’s lengthy book does full justice to the tragedy in the history of these two men—a tragedy in the broadest sense because neither man fully comprehended the complicated circumstances with which they struggled or appreciated the long-term consequences of their actions. By 1802 Hamilton did glimpse that his future role in America was limited. “Mine is an odd destiny,” he wrote to a friend. Although no American had done more to prop up “the frail and worthless fabric” of the Constitution, he had received nothing but “the murmurs of its friends” and “the curses of its foes” for his reward. What could he do, he said, except withdraw from the scene? “Every day proves to me more and more that this American world was not meant for me.”

He was right. Fast-moving developments were overwhelming nearly all of his noble and aristocratic aims. Hamilton misread the future and was never in control of events. He never really understood the way the American economy was developing. He and the other Federalists tended to favor big merchants and financiers and to ignore artisans, small businessmen, and farmers. Hamilton expected his Bank of the United States (BUS) to create several branches that would eventually absorb the state banks and give the BUS a monopoly of the nation’s banking—something that never happened. Moreover, his BUS was intended to make credit available only to large merchants engaged in overseas commerce and others who wanted short-term loans of ninety days or less. But ordinary money-minded folk, farmers and artisans, wanted long-term credit and paper money with which to trade. Consequently, despite Article I, Section 10 of the Constitution, which prohibited the states from issuing paper money, the states began chartering dozens of banks that offered all these proto-businessmen lots of paper money—much to the horror of Hamilton and other Federalists.

Despite Hamilton’s interest in economic diversity and manufacturing, he and his fellow Federalists were insensitive to the entrepreneurial needs and interests of these ordinary farmers, artisans, and other small businessmen. His tariffs were not protective; they were revenue-raising measures. Indeed, he did not like protective tariffs, preferring to give bounties to the manufacturers instead. Those bounties tended to benefit manufacturers who exported articles rather than those who manufactured goods for domestic consumption.

In fact, Hamilton and the Federalists tended to think of commerce almost exclusively in the traditional terms of overseas trade. Consequently, they ignored the significance of the developing domestic market, which soon came to dominate American business in the burgeoning northern states. It is thus not surprising that the artisan-manufacturers and other businessmen, who had been strong supporters of the Federalists in 1787–1788, went over to the Jeffersonian Republicans in ever-increasing numbers.

One of the leaders of these Democratic- Republican artisan-manufacturers was Aaron Burr. Burr with his pragmatic, disingenuous, opportunistic, finger-to-the-wind manner represented the democratic future of American politics. Hamilton sensed that. The night before his fatal duel he foresaw “the Dismemberment of our Empire,” which would solve nothing, for “our real Disease,” he said, “is Democracy, the poison of which by a subdivision will only be the more concentrated in each part, and consequently the more virulent.”

Gore Vidal was very clever in characterizing Martin Van Buren in his novel Burr as the illegitimate son of Aaron Burr; for in an important political sense Van Buren was the offspring of Burr’s precocious brand of popular politics. More than any other major figure Van Buren came to epitomize the new breed of democratic politicians who succeeded the generation of the founders. Unlike the founders, Van Buren believed in political parties and in running, not standing, for office. He was the first modern professional politician to win the presidency.

As the ambitious son of a tavern keeper, Van Buren prided himself on having risen to office “without the aid of powerful family connextions.” Before winning office, he had achieved very little. He had won no battles, had written no great treatises, had made no memorable speeches. He had no public charisma and was barely known throughout the United States. But what this “little magician” had done was build the best and most organized political party the country had ever seen.

Van Buren knew he lived in a new and different world from that of the founders. He told the New York constitutional convention of 1820–1821 that Americans could not rely on the old-fashioned views of the Revolutionary generation any longer. They had to rely on their own experience, not on what those Founders said and thought. They had many “fears,” he said; they had “fearful forebodings” of democracy that American experience had not borne out. Since Burr had anticipated that democracy more accurately than any of the Founders, maybe he should get equal billing after all.

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story