The myth of Delmore Schwartz is a variant on the myth of the visionary modern poet, at once preternaturally gifted yet unable to live in the world. This Romantic image starts, perhaps, with Thomas Chatterton, the eighteenth-century prodigy from Bristol who wrote counterfeit medieval texts and committed suicide at seventeen. It gained intensity in the life stories of John Keats and Percy Shelley, who both died in their twenties, and most spectacularly with the Frenchman Arthur Rimbaud, who made himself a seer through “the derangement of all the senses” before he stopped writing at twenty.

“We Poets in our youth begin in gladness;/But thereof come in the end despondency and madness,” wrote William Wordsworth, a government functionary who in old age became poet laureate. Wordsworth’s stolid life didn’t fit his radical formula; still, his apothegm, which suggests that poets are fired at first by illumination but fly too close to the sun and flame out, took tenacious hold.

In the twentieth century in the United States, the mantle of maladjustment was taken up by any number of poets, among them a group of East Coast writers who came into their majority just before World War II. Delmore Schwartz called them “the class of 1930,” and besides him they included his younger compeers John Berryman, Randall Jarrell, and Robert Lowell. (Their female counterparts Elizabeth Bishop, Sylvia Plath, Adrienne Rich, Anne Sexton, and others lived their own various versions of the myth.) All would have troubled lives and die early or unnatural deaths. Eileen Simpson, who was Berryman’s first wife, wrote a shrewd, disabused, and moving memoir about them, Poets in Their Youth (1982), its title taken from Wordsworth’s couplet.

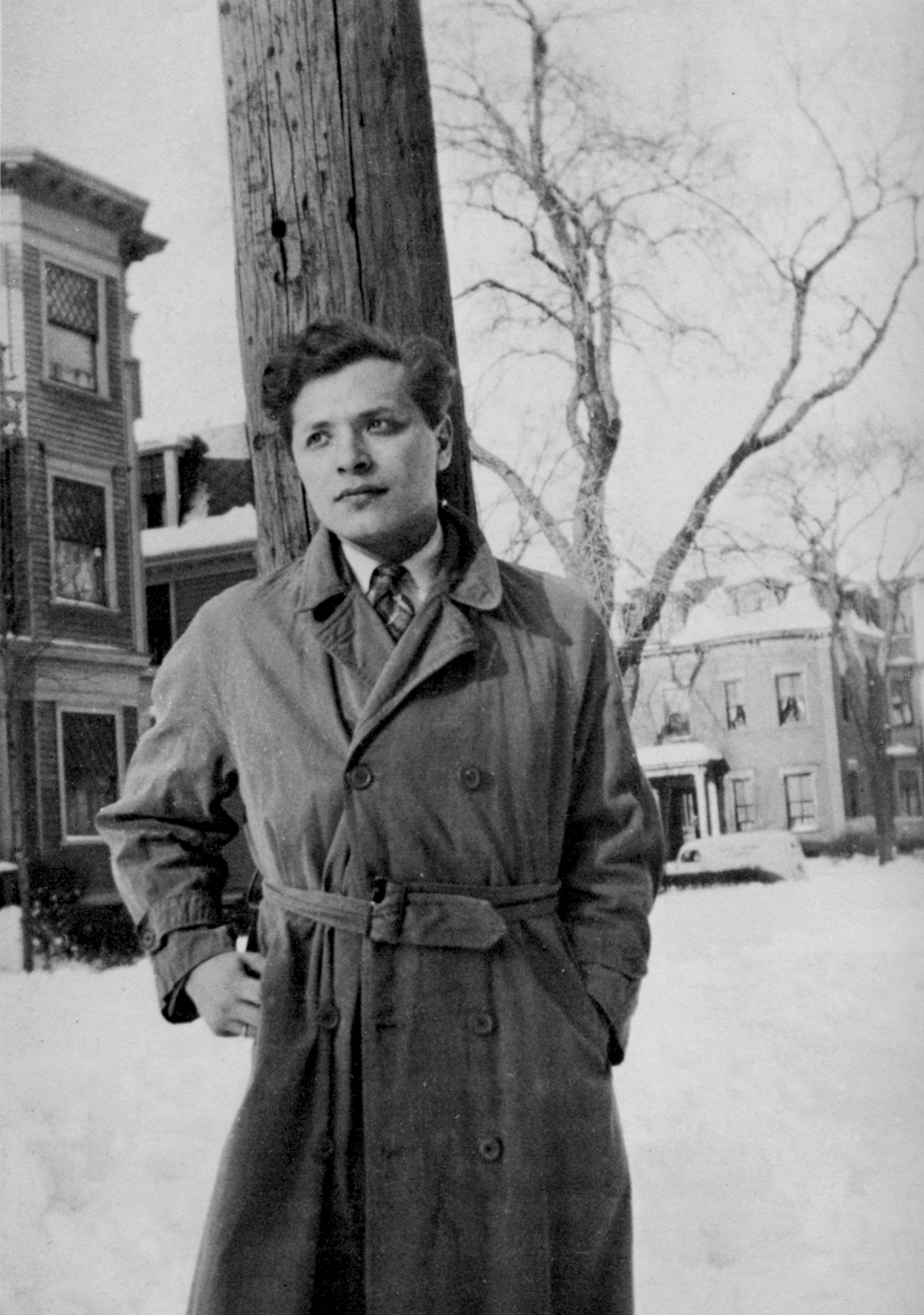

Delmore—“I never heard anybody call him ‘Schwartz,’” wrote his friend and occasional antagonist Dwight Macdonald—was born in Brooklyn to Jewish immigrants from Romania. They soon separated and his father, a philandering real estate wheeler-dealer, moved west and died when Delmore was still in high school; he never received the inheritance due him. He inhaled the precariousness and the exhilaration of his parents’ situation. His old friend John Berryman says Delmore “sang” this Virgilian parody to him as a young man:

I am the Brooklyn poet Delmore Schwartz

Harms & the child I sing, two parents’ torts

For his contemporary the critic Alfred Kazin, who shared a similar background, “to achieve success in life was a compulsion passed on from immigrant fathers to their sons. I was the first American child: their offering to the strange new God; I was to be the monument of their liberation from the shame of being—what they were.” Delmore thus exhibited both “chutzpah and social malaise,” as his second wife, Elizabeth Pollet, put it. “He and his friends assumed their own genius”—and others were quick to concur.1 Kazin told James Atlas, Schwartz’s biographer, that Delmore was “the genius, the writer of the old Partisan gang”—that is, of the writers around the “inky, thinky,” tendentious, radical literary review that set the intellectual tone in a certain swath of left-wing 1930s New York.

Philip Rahv, Partisan Review’s dominant editor, printed Delmore’s greatest story, “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities,” written when he was only twenty-one, which immortalizes the generational divide between immigrant parents and their partly assimilated, wounded, all-too-knowing children, at the beginning of the first issue in which the magazine was relaunched as an anti-Stalinist journal. Rahv, while impressed with Delmore’s precocity and charm, was not won over by his ingratiating manner, borrowed no doubt from his confidence-man father—Macdonald called his friend “an intellectual equivalent of the Borscht Circuit tummler.” Rahv was also envious of Delmore’s sexual allure, complaining that “poets get all the girls.” Delmore, for his part, saw through Rahv’s self-serving pretensions, branding him “manic-impressive.” “Philip does have scruples,” he liked to say, “but he never lets them stand in his way.”2

Delmore’s first book of poems, also called In Dreams Begin Responsibilities and including the famous story, was published in 1938, when he was twenty-four. It won him kudos from the likes of T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens, John Crowe Ransom, and William Carlos Williams. His publisher, the ever-prescient James Laughlin, called him “The American Auden,” and the critic F.W. Dupee agreed, declaring that “since Auden’s early poems appeared, there has been no verse so alive with contemporary meaning.” Allen Tate saw Delmore as “the first real innovation that we’ve had since Eliot and Pound.” Not everyone was snowed, however; Louise Bogan in The Nation criticized the potpourri of fashionable borrowings in Delmore’s poems: “The Kafka-Auden-Isherwood Dog, a monocle and some ice cream from W. Stevens, playing cards from Eliot, and Anglo-Saxon monosyllables from Molly Bloom.”

Atlas tells us that “the failure of life’s hopes had become [Delmore’s] obsessive theme before he was twenty-five,” and despite his early fame, which won him teaching jobs at Harvard, Princeton, Chicago, UCLA, and elsewhere, editorial positions at Partisan Review and The New Republic, and distinguished prizes, he proved unable to build on his early success. For Kazin, Delmore “believed in nothing so much as the virtue and reason of poetry,” but as Atlas writes, his absorption with literary politics conflicted with his sense of poetry’s nobility, and “the more influential he became, the more he decried the lot of the writer in America.”

Advertisement

His long autobiographical poem, Genesis (1943) (“Keep thinking all the time, O New York boy!”) was Delmore’s entry in the modernist epic sweepstakes. As Craig Morgan Teicher, the editor of the new selection of his writings, notes, it was his “most ambitious and least successful work,” widely considered a failure, as were his turgid verse dramas Dr. Bergen’s Belief and Shenandoah, whose protagonist, the resonantly named Shenandoah Fish, has written “a satirical dialog between Freud and Marx” that is not unlike Delmore’s unreadable closet drama Coriolanus and His Mother.

Other books of poems and stories followed, and other awards, though not the novels for which he made extensive notes. Delmore was married and divorced twice. Alcohol and paranoia slowly consumed him; there were hospitalizations, and he grew estranged from his old friends, though Philip Booth, a colleague at Syracuse, where he held his last teaching position in the 1960s, said, “Delmore exerts a moral force just when he paces the hall.” He died of a heart attack in a fleabag hotel off Times Square, alone and mad, in 1966, aged fifty-two.

Delmore’s story has been indelibly told in Atlas’s exemplary biography, which, along with Saul Bellow’s portrait in Humboldt’s Gift,3 his 1975 novel based on his relationship with Schwartz, are the urtexts of the Schwartz cult—along with memorials by Berryman, Lowell, and others. All have given impetus over the years to revivals of interest in him and his work.

There are two primary vectors in Schwartz’s writing. First is the myth of origins. As the son of immigrants, Delmore is obsessed with, and shaped by, “the enigma of arrival,” which is also the story of his generation of Jewish intellectuals, and Atlas praises “Delmore’s mastery of the tone of Jewish life.” Contrapuntal to this is his unquestioning adherence to what would come to be called the Great Tradition. Shakespeare and James are regularly invoked as guarantors of his own highbrow commitments, his passport out of Brooklyn. If his anecdotal style was Jewish, his literary voice is goyisch High Serious, with an up-to-date overlay of Auden, whose “rugged, crabbed hard language with the kind of ‘implicatory’ power which is always a sign of mastery” Delmore deeply admired. Atlas says he “was drawn to Baudelaire’s emphatic style of declamation—except that in Delmore’s voice defiance was tempered by a note of ineffable sorrow.” Listen to how a Brooklyn beach scene, through the eyes of “the novelist tangential” who is a stand-in for the poet, comes alive as socialist pastoral:

“the cure of souls.”

Henry James

The radiant soda of the seashore fashions

Fun, foam, and freedom. The sea laves

The shaven sand. And the light sways forward

On the self-destroying waves.

The rigor of the weekday is cast aside with shoes,

With business suits and the traffic’s motion;

The lolling man lies with the passionate sun,

Or is drunken in the ocean.

A socialist health takes hold of the adult,

He is stripped of his class in the bathing-suit,

He returns to the children digging at summer,

A melon-like fruit.

O glittering and rocking and bursting and blue

—Eternities of sea and sky shadow no pleasure:

Time unheard moves and the heart of man is eaten

Consummately at leisure.

The novelist tangential on the boardwalk overhead

Seeks his cure of souls in his own anxious gaze.

“Here,” he says, “With whom?” he asks, “This?” he questions,

“What tedium, what blaze?”

“What satisfaction, fruit? What transit, heaven?

Criminal? justified? arrived at what June?”

That nervous conscience amid the concessions

Is a haunting, haunted moon.

Schwartz is attempting a new kind of American poetry here, in his own industrial-urban tone, inflected with the intellectual/political enthusiasms of his moment. But it proved an uphill battle; he came to feel, to his great pain, that Eliot and James were “hideous snobs,” and that he was somehow excluded from membership in the modernist final club; this awareness contributed to destabilizing “feelings of self-distrust and conflict of mind”:

The ghosts of James and Peirce in Harvard Yard

At star-pierced midnight, after the chapel bell

(Episcopalian! palian! the ringing soared)

Stare at me now as if they wish me well.

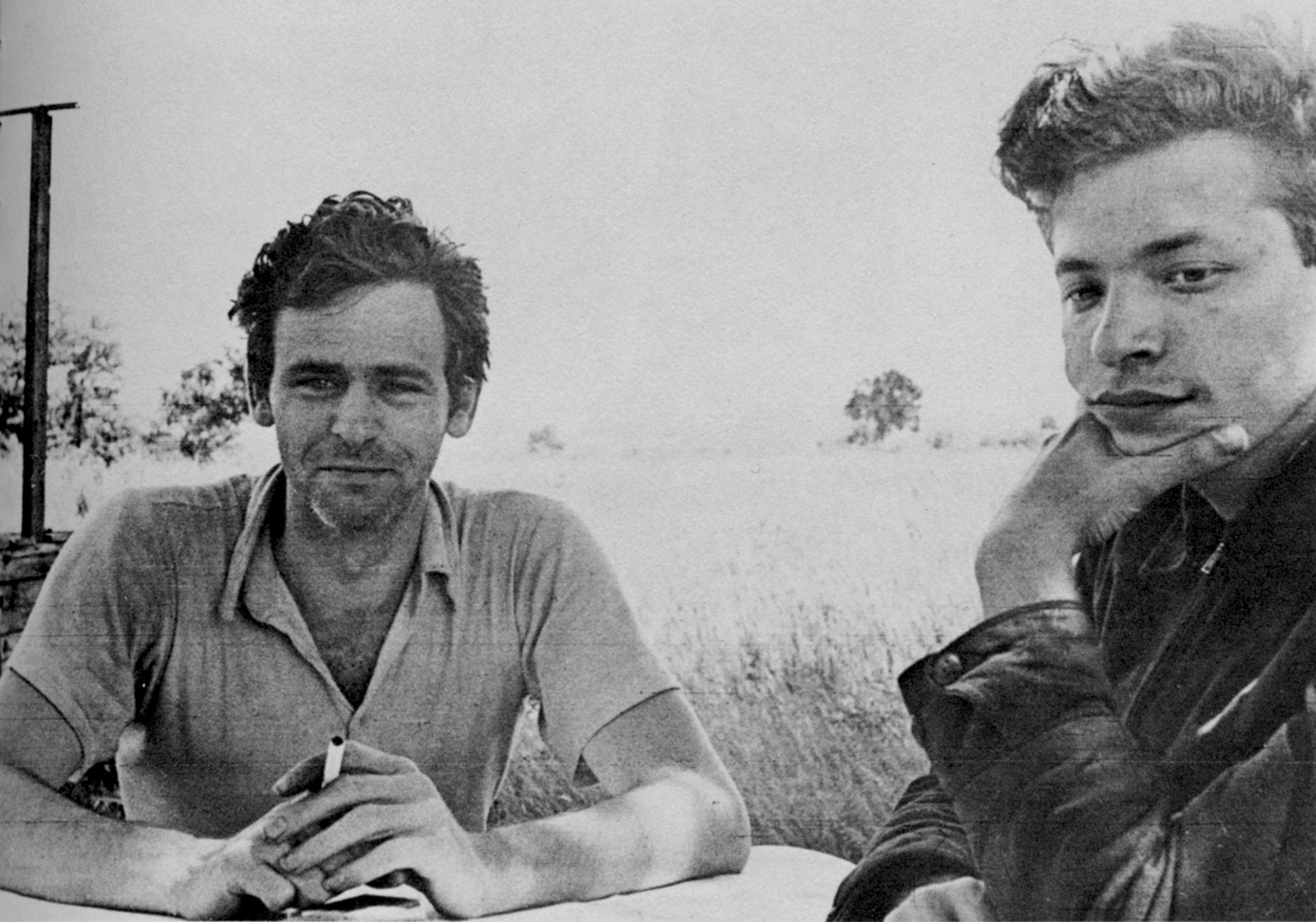

“We couldn’t even keep the furnace lit!” Lowell exclaimed in a poem about the ill-fated year that he and his first wife, Jean Stafford, shared a house in Cambridge with Delmore:

Advertisement

We drank and eyed

The chicken-hearted shadows of the world.

Underseas fellows, nobly mad,

we talked away our friends….4

After Schwartz’s death, Lowell wrote to Elizabeth Bishop that it had been

an intimate grueling year…Jean and he and I, sedentary, indoors souls, talking about books and literary gossip over glasses of milk, strengthened with Maine vodka…Delmore…husky-voiced, unhealthy,…quickening with Jewish humor, and in-the-knowness, and his own genius, every person, every book—motives for everything, Freud in his blood, great webs of causation, then suspicion, then rushes of rage…. Too much, too much for us…!5

Schwartz’s mania, his mounting paranoia, were indices of the illness that was eventually his undoing (that Lowell himself suffered not unrelated torment lends his portrayal of Schwartz a gruesome poignancy).

Delmore himself writes, introducing his translation of Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell, published by Laughlin’s New Directions in 1939, that Rimbaud’s book

is a record of the track which any poet must run when, for whatever reason, his attempt is to reject everything he has inherited (to be a poet, one might say, is to be an heir), and by himself and by his poetry attain to a new vision of life….

He adds: “Probably such an effort is a permanent tendency of the poetic mind, one which is bound to recur whenever the community cannot satisfy or sustain the poet.”

Delmore is talking about himself here, as writers inevitably are, about his inability to get beyond his struggle with his inheritance into matter that would truly be his own. In Bellow’s novel, Von Humboldt Fleisher, the Schwartz character, is a “hero of wretchedness,” “intent,” as Atlas puts it, “on settling ontological scores through more practical instruments.” Humboldt, Bellow writes,

consented to the monopoly of power and interest held by money, politics, law, rationality, technology because he couldn’t find the next thing, the new thing, the necessary thing for poets to do.

He “wanted to drape the world in radiance, but he didn’t have enough material…. The radiance he dealt with was the old radiance and it was in short supply. What we needed was a new radiance altogether.”

It’s hard to make out the principles that motivate Teicher’s selections in Once and for All. His intent, he writes, is to provide an “accurate sense of the development of Schwartz’s art,” but the development feels like a decline. Many of the great set pieces are here: “In Dreams Begin Responsibilities” and poems like “In the Naked Bed, in Plato’s Cave” and “The Heavy Bear Who Goes with Me”; but I found myself wondering why, for instance, we need to page through the humorless Dr. Bergen’s Belief. It is interesting, though, to sample selections from Delmore’s unfinished study of Eliot’s poetry and a few of his intemperate letters to his long-suffering editor, Laughlin. And one cheers when, after reading Pound’s anti-Semitic diatribes in his Guide to Kulchur, Delmore tells him, “I want to resign as one of your most studious and faithful admirers.”

What is truly helpful in Once and For All is John Ashbery’s introduction, with its revelatory reading of Schwartz’s work, in particular his identification of “the electric compressions and simplifications” of Delmore’s great early poetry, whose subject is always inevitably himself. As Ashbery writes: “His work is really all of a piece, the same retelling of birth, migration, new disappointment, damaged hopes, ordinary lives being turned into the stone of history.” Ashbery, perhaps unsurprisingly, makes a kind of case for the later work in the beautifully named selected poems of 1959, Summer Knowledge (Delmore’s titles were poems in themselves; Ashbery says they “inveigle and buttonhole the reader in the manner of the Ancient Mariner”). Atlas calls the late poetry “haphazard, euphonious, virtually incomprehensible” but Ashbery discerns in it almost “a new kind of telling, with an urgent bluntness of its own.”

The critic Michael Clune has written about Ashbery that the basic unit of his poetic practice is not the book, or even the poem, but the line. I think the same can be said for Delmore; apart from his few best poems, what really stays with the reader are individual lines, some of them employed, with slight variations, as titles:

The heavy bear who goes with me…

In the naked bed, in Plato’s cave…

The beautiful American word, Sure…

Tired and unhappy, you think of houses…

We are Shakespearean, we are strangers.

The mind is a city like London, Smoky and populous…

The actual is like a moist handshake, damp with nervousness or the body’s heat.

It’s impossible to gainsay the brilliance of these phrases, even when great poems fail to rise out of them. As Pollet said of Delmore’s voluminous diaries: “He begins the journals conscious of it as a literary form and therefore conscious of a potential audience. But the focus and coherence this implies is [sic] not sustained.” For Pollet he was sometimes “the poet, the Orpheus, transcending this world to make music out of things he alone had penetrated to and heard”; at others, he was “the wounded genius, the heavy bear of his poems, the naïf scheming to be practical in impractical ways.”

Today, the literature of identity, which so obsessed Delmore, is the province of others claiming their rightful place in the American cavalcade. As will be eventually true for them, too, no doubt, what remains alive in Delmore has less to do with his quest than with the ways he devised to evoke it. What he was expressing—the newcomer’s dislocation, the urge to grab life by the lapels, to be heard, to prevail—is universal, and therefore much less remarkable than the lightning strikes in which he gave it voice. Delmore’s genius survives in the sound of his words, in his hypnotizing lines. Their sound is their ultimate sense, since we read poetry, finally, less for what it says than how.

The myth of Delmore is a myth of the vicissitudes of assimilation and the travails and idiosyncracies of the poetic temperament. He is, in his own way, a perpetual adolescent, a kind of careerist Brooklyn Rimbaud, never able to extricate himself from his fatal family romance. Had he died young, he might have been an avatar of unfulfilled promise, a one-name wonder. Instead, he lives on as a tragic exemplar of arrested development. Berryman, in his grieving “Dream Songs” for Delmore, writes: “His mission was real,/but obscure.” He recalls his friend as “the whole young man/alive with surplus love,” who “undermined/his closest loves with merciless suspicion.”

In his best work, Delmore lives on perpetually young, perpetually aspiring and anxious, and its power and intensity keep on creating disciples. Lou Reed, his student at Syracuse in his last years, said, “I wanted to write. One line as good as yours. My mountain. My inspiration.”

Let Berryman have the last word:

The spirit & the joy, in memory

live of him on, the young will read his young verse

for as long as such things go…

-

1

Portrait of Delmore: Journals and Notes of Delmore Schwartz, 1939–1959, edited by Elizabeth Pollet (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1986), p. x. ↩

-

2

James Atlas, Delmore Schwartz: The Life of an American Poet (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977); see the review in these pages by Robert Towers, March 23, 1978. ↩

-

3

Atlas says, “There is a certain bitterness in Bellow’s portrait…that leads him to exaggerate Delmore’s vindictive qualities.” ↩

-

4

“To Delmore Schwartz (Cambridge, 1946)” in Life Studies (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1959). In Lowell’s poem he quotes Schwartz repeating Wordsworth: “We poets in our youth begin in sadness;/thereof in the end come despondency and madness”; but according to Lowell’s biographer Paul Mariani, Schwartz, on reading Lowell’s poem, wrote him that he had looked up what he had written in 1946—something much more clever and bitter: “We poets in our youth begin in sadness/But thereof come, for some, exaltation,/ascendancy and gladness.” See Lowell, Collected Poems, edited by Frank Bidart and David Gewanter (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003), p. 1037. ↩

-

5

Lowell to Elizabeth Bishop, July 16, 1966, in Words in Air: The Complete Correspondence between Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, edited by Thomas Travisano with Saskia Hamilton (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), p. 603. ↩