When the abolitionist William Wells Brown said that “Slavery has never been represented; slavery never can be represented,” it wasn’t because he didn’t mean to try. The writer, ex-slave, and orator (1814–1884) would spend most of his career testifying to the realities of bondage, in speeches, memoirs, a novel, a play, and eventually, as though frustrated with words, in magic lantern slides—“William Wells Brown’s Original Panoramic Views of the Scenes in the Life of an American Slave.”

Today, slavery remains the American unrepresentable. It is the perennial confession of the national conscience, perpetually on the verge of being made. Somehow, it is always new—every book, film, and television show on the subject is praised as a reckoning with history or pilloried as a desecration of it, and treated either way as the breach of a long silence. And yet it has been more than twenty years since Toni Morrison’s Beloved won the Pulitzer Prize; forty since LeVar Burton declared “My name is Kunta Kinte” in Roots; almost two hundred since Henry Wadsworth Longfellow sighed over “The hunted Negro” in “the dark fens of the Dismal Swamp.” Longfellow could have written for John Legend’s new series Underground; as the show opens, Kanye West’s chaos anthem “Black Skinhead” sets the tempo for a slave hunt: “But there’s nowhere to go now!/And there’s no way to slow down!”

Has the art of slavery become an escape from the American present, a means of avoiding ourselves? In Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’s play An Octoroon (2014), the author-surrogate, a black playwright, decides to stage Dion Boucicault’s The Octoroon (1859) while in therapy. Reviving a plantation melodrama seems to him the best way to face the existential dread of our contemporary racial psychosis.

You could easily put the country on the same couch. It seems hardly an accident that films like Django Unchained, 12 Years a Slave, and Free State of Jones—stories of exceptional Negroes and white saviors triumphing over oppression—have become so popular precisely at this moment. As though compared to the police killings of unarmed black people, the rise of the carceral state, and the return of explicit white supremacy to national politics, slave stories don’t look so bad—at least they have a happy ending that everybody knows. And so they have become part of that vast placebo politics that is our antebellum nostalgia: slave ship splinters at the new Smithsonian; the revenge of Quentin Tarantino’s Django; Harriet Tubman on the twenty-dollar bill.

Cora, the skeptical heroine of Colson Whitehead’s new novel, is well acquainted with the pitfalls of “remembrance.” A runaway from slavery, she is equally a fugitive from the distraction of its commemoration—something she discovers when, newly escaped from Georgia, she promptly finds herself exhibited in a diorama of slave life. Complete with a quaint cabin and a model slave ship (captained by a smiling wax skipper), the show is history as visitors want to imagine it—comfortable, contained, and leaving them out.

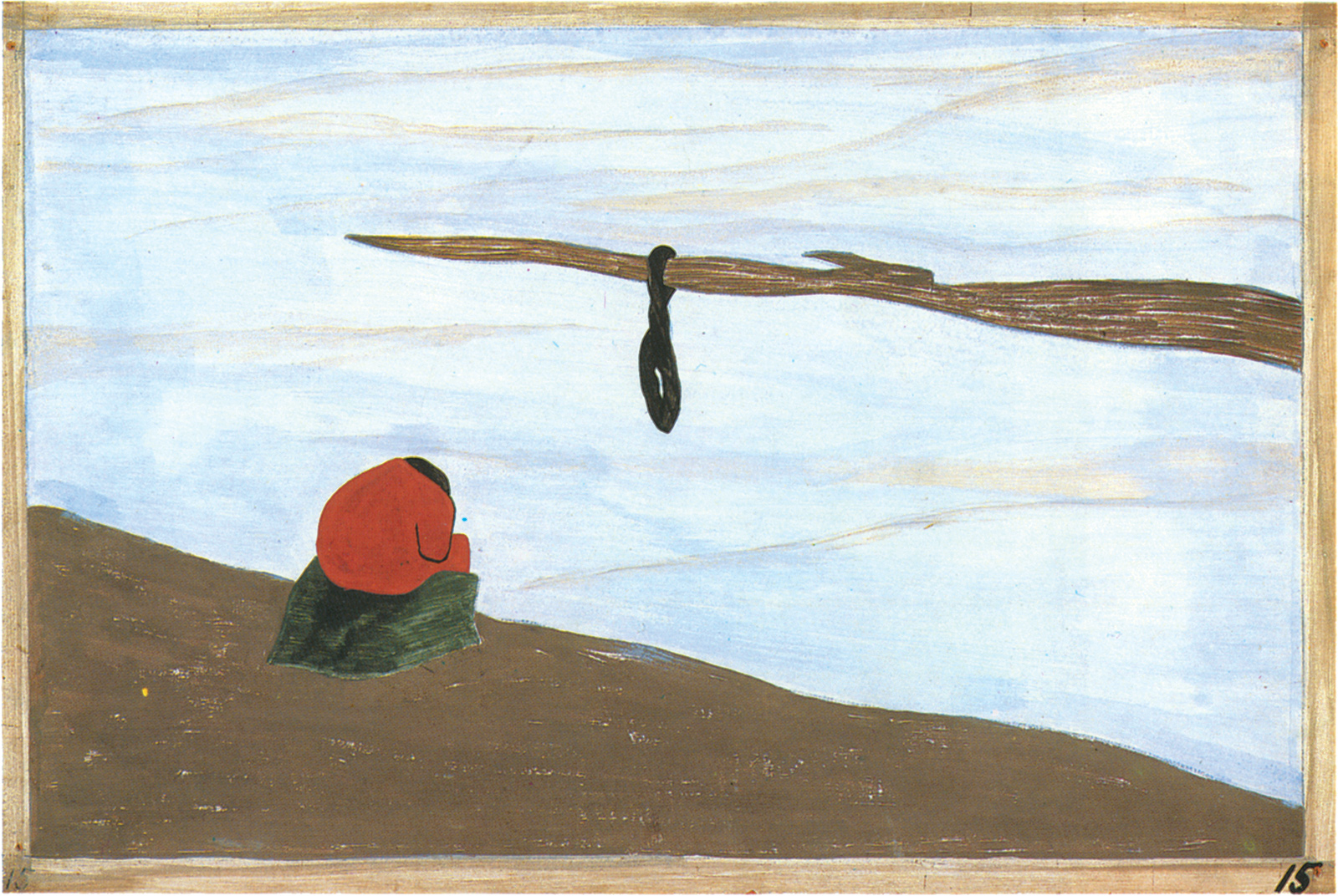

It is in other words the kind of history one might expect from a book called The Underground Railroad, a title suggestive of the feel-good pictogram past of children’s books. (And even, bizarrely, the decals of U-Haul trucks. Since 2009, many have been adorned with the likeness of Harriet Tubman.) Whitehead’s novel is anything but this kind of story. His alternate America is a world of skyscrapers and slave coffles, recognizably nineteenth-century but taking place as though on a different fork of time. The Civil War seems never to have occurred, and the slavery question has resolved itself otherwise. While the Deep South still has it, the Carolinas have abolished it, replacing it with new depredations of black life. North Carolina has a government of brutal white supremacists, who have abolished not only slavery but also the former slaves. On the roads in and out of the state, corpses hang in a line from the trees of a gruesome “Freedom Trail.”

South Carolina is controlled by a more subtle cabal, who are promoting a program of “uplift” for the emancipated. The government has opened up a hospital and dormitories for the newly free, along with the “Museum of Natural Wonders” where Cora is exhibited. There, in the rearview mirror of “progress,” she appears as the living miniature of a past put to rest.

Until she starts looking back:

She got good at her evil eye. Looking up from the slave wheel or the hut’s glass fire to pin a person in place like one of the beetles or mites in the insect exhibits. They always broke, the people, not expecting this weird attack, staggering back or looking at the floor or forcing their companions to pull them away. It was a fine lesson, Cora thought, to learn that the slave, the African in your midst, is looking at you, too.

The South Carolina that Cora looks out at—and that gazes so smugly at the pat myth of its past—is busy ushering its black population into a sinister future. Cora and her companion Caesar soon discover that the state has embarked on finding a solution to its “negro problem,” a long-term project of control and extermination to which abolition was only an opening act. The new hospital is conducting medical experiments on unwitting black patients and sterilizing black women; in a local saloon, a doctor brags about breeding the freedmen for desired traits.

Advertisement

These eugenic horrors, far beyond the slavery-era timeline, are excerpts from a country much closer to our present. They are cross-cut from the Tuskegee syphilis experiments and the hospitals where as late as 1974, tens of thousands of black women were sterilized against their will. The anachronism is startling, out of place in a genre that traditionally centers on the runaway’s inspiring journey. Which is precisely Whitehead’s point.

The Underground Railroad isn’t the modern slave narrative it first appears to be. It is something grander and more piercing, a dazzling antebellum anti-myth in which the fugitive’s search for freedom—now so marketable and familiar—becomes a kind of Trojan horse. Crouched within it are the never-ending nightmares of slavery’s aftermath: the bloody disappointments, usually sidelined by film and fiction, that took place between the Civil War and civil rights. In Whitehead’s hands the runaway’s all-American story—grit, struggle, reward—becomes instead a grim Voltairean odyssey, a subterranean journey through the uncharted epochs of unfreedom.

Like his South Carolina, Whitehead’s grisly North Carolina is set in the time of slavery. But it also recalls the state’s 1898 Wilmington insurrection, when the city’s interracial government was deposed by a mob of armed, self-avowed white supremacists—“Red Shirts” much like the night riders of the novel. Over the course of a day, dozens of black residents were shot or lynched. Part of the so-called redemption of the South, the uprising laid the groundwork for more than half a century of Jim Crow segregation. As W.E.B. Du Bois put it in Black Reconstruction: “The slave went free; stood a brief moment in the sun; then moved back toward slavery.”

The art of Whitehead’s alternate timeline is in the way he removes this “brief moment in the sun”—in history, the event of emancipation; in fiction, the catharsis of “freedom.” (Or in the darker variant of fugitive stories, martyrdom.) His runaway characters pass directly from slavery into what succeeded it, each era sewn seamlessly into the same fictional world. Cora’s journey through that world, and her search for freedom within it, begins to take on the unreal dimensions of allegory—no longer a heroic escape, but instead a winding pilgrimage; the runaway’s progress become Sisyphean critique.

Colson Whitehead isn’t the first person you’d expect to write The Underground Railroad. His last book, The Noble Hustle (2014), was a gambling memoir beginning with the sentence: “I have a good poker face because I am half dead inside.” Before that he published Zone One (2011), a post-apocalyptic zombie novel set in Manhattan, and Sag Harbor (2009), a bildungsroman about the summer misadventures of black teenagers in the Hamptons.

Gambling, body-snatching horror, and the idiosyncrasies of vacation communities aren’t the likeliest lead-up to a slave narrative. Then again, there are no body snatchers quite like slave catchers; no vacation quite like leaving the plantation; no gambles higher-stakes than the ones runaways made with their lives. Nevertheless, closer to Whitehead’s Underground Railroad are his earlier, more historically minded novels, which use the ersatz pasts of legend and commemoration to access the deeper histories beneath them.

John Henry Days (2001) unearths the multigenerational epic of John Henry, the legendary steel driver and blues-ballad hero, from the festivities around a postage stamp released in his honor. Apex Hides the Hurt (2006) has a similar structure—a “nomenclature consultant” hired to rename and rebrand the largely white town of Winthrop uncovers the story of the black freedmen who settled it.

But The Underground Railroad’s truest forerunner is The Intuitionist (1999), Whitehead’s magical debut. Lila Mae Watson, the main character, is the first black woman in an arcane guild of elevator inspectors. She works in an unnamed city in the early twentieth century, where she is assigned to supervise the elevators at a federal office building named after a runaway slave. The assignment is a superficial demonstration of racial progress—up from slavery and all the way to the hundredth floor.

Advertisement

Racial uplift doesn’t last; when an elevator goes into free fall, Lila is scapegoated by the inspectors and suspended from the guild. Her investigation of the accident leads her to the writings of James Fulton, a black inventor and elevator visionary. His prophesies of a great “second elevation” track the story of the Great Migration, when millions of black southerners found new lives in unfamiliar (and often hostile) northern cities. Whitehead makes elevators the mirror of this vast human aspiration—and, by indirection, a way to criticize the way we remember it.

From bus boycotts to freedom rides, the Amistad to Marcus Garvey’s “Black Star Line,” vehicles have always been attractive synecdoches for the black freedom struggle. And the Underground Railroad is the oldest of them all, thought up in 1839 when a Washington newspaper speculated that a fugitive had taken a railcar “underground all the way to Boston.” The metaphor took off. It made deeper inroads after the Civil War, in an era often called the “nadir” of race relations, when the United States largely abandoned black southerners to poverty, disenfranchisement, and lynch law. Not for the last time in American history, progressive whites sought an escape from this racial present in the stylized struggles of bygone days.

And the Underground Railroad provided it. With more than a touch of what is now called white savior syndrome—not to mention sheer exaggeration—historians like Wilbur Siebert and Homer Uri Johnson enshrined the Underground Railroad and its heroic conductors as the great apparatus of abolition:

It was most efficiently officered, and had its side tracks, connections and switches…its station agents and conductors, men undaunted in danger and unswerving in their adherence to principle; its system of cypher dispatches, tokens and nomenclature which no attache ever revealed.

Whitehead’s novel takes this grandiose metaphor and makes it real, guiding its runaway characters through a subterranean underground connecting Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, and Indiana. But his railroad is little like the emancipation superhighway imagined by abolitionists—a metaphor in which the railroad’s techno-optimism underwrites the inevitability of freedom. It is, instead, an incomplete warren of provisional refuge—a maze filled with precarious junctions and alarming dead ends. One station is entombed beneath a collapsed mica mine; another slumbers under the ashes of an abolitionist’s burned parlor. Trains don’t go straight north but instead carry their passengers to the next ad hoc refuge, each station rough-hewn from the nation’s recalcitrant rock.

Whitehead’s fantastic conceit is a leaf taken from a tradition of speculative slave narratives. The way Cora’s journey superimposes eras—each state standing in for a stage in American white supremacy—recalls the time travel of Octavia Butler’s classic Kindred (1979), the story of a black woman who (accompanied by her white husband) is transported back in time to a plantation. Even nearer to Whitehead’s derailment of antebellum history is Ishmael Reed’s Flight to Canada (1976). A satirical “neo–slave narrative” (Reed’s term), the novel wittily conjoins the past of slavery to the present of America’s bicentennial. The two times are bound by humorous, incisive anachronisms—none more unforgettable than the runaway protagonist’s escape. Skipping the usual swamps and frozen rivers, Raven Quickskill takes a jet plane to Canada: “Traveling in style/Beats craning your neck after/The North Star and hiding in/Bushes anytime, Massa.”

There is more than a little of Quickskill’s jet (and of Reed) in Whitehead’s Underground Railroad. But if Reed wrote his “neo–slave narrative” to make slavery immediate—to resurrect it in a culture in which it was still largely distorted or ignored—Whitehead has written his in a contemporary setting almost exactly opposite. Slavery is omnipresent, an almost anodyne subject, grafted onto America’s self-regarding romance with progress and the individual’s rugged freedom.

It was D.H. Lawrence who called the United States “a vast republic of escaped slaves.” He referred not to the enslaved and their descendants but to white Americans—runaways, in his eyes, because their concept of liberty had always meant escape. “They didn’t come for freedom,” he writes of the Pilgrims, the Western pioneers, the first Virginia planters, not “positive freedom, that is. They came largely to get away.”

This romance with negative freedom, with freedom from, shows in the way Americans have for hundreds of years consumed and identified with the stories of fugitive slaves—people who never seem to be going anywhere, but only ever “getting away.” It is “getting away” when Whitman in The Song of Myself writes, “I am the hounded slave, I wince at the bite of the dogs”; when at the end of the film, Tarantino’s Django abandons his caged comrades and rides off into the sunset. But the atomized freedom that so many depictions envision is not the same as the positive freedom many enslaved people actually sought. The difficult search for this other freedom, the freedom to build and belong in an unmolested community, is less easily assimilable to “universal” narratives of individual striving—stories often said to “transcend race.”

The drama of the black fugitive hero, pursued by wicked slaveholders, is one that goes down easy; much less the survival struggles of black communities amid white ones that wanted them destroyed. We see plenty of characters like Simon Legree and Calvin Candie; not so the mobs that burned down the homes of abolitionists; that destroyed the “Black Wall Street” of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1921; that in the July 1863 Draft Riots, the largest urban insurrection in American history, burned black orphanages in New York. Which is why Colson Whitehead’s quietly radical gesture in The Underground Railroad is his replacement of the fugitive individual—wrestling with herself and nature in search of an abstract freedom—with the fugitive community, fighting for an inch of free soil in enemy terrain.

Home is the one great question of the novel’s runaways—it is what the country they live in doesn’t want them to have. They try for it anyway, grim-faced pioneers in a world of white bandits. When they do find shelter, it is in fragile families of circumstance, pan-flash communities quickly snuffed out. On the Georgia plantation where Cora is born, shelter is the small garden she tends, the quarters where she lives with other “misfit” women, or the once or twice a year when Old Jockey, the eldest slave on the plantation, declares his birthday. As Cora escapes from slavery she finds larger communities among the freedmen of South Carolina, the agents of the Underground Railroad, and ultimately the founders of Valentine farm: a “black nation rising” in the fields of Indiana. The circles of sanctuary grow larger. So too does the violence of their destruction, and the velocity—mirrored in the novel’s style—of their unsettlement.

Whitehead’s prose is quick as a runaway’s footsteps, light as her shoulder-mounted bindle bag. You can feel it from The Underground Railroad’s first chapter, the story of Cora’s grandmother Ajarry. Kidnapped by Dahomean raiders and shipped across the sea, Ajarry’s life passes in a whir of narration only six pages in length. Catastrophes go by like a mute film on fast-forward—raped in the hold, father’s head stove in, exchanged for rum and gunpowder by slavers. Four buried children, three marriages ended by death or at auction, dozens of sales across the country. “And so on.” An inventory of misfortunes, suggestive of a race between Ajarry’s mind and the ever-mutating intelligence of slavery: “Since the night she was kidnapped she had been appraised and reappraised, each day waking upon the pan of a new scale.” Ajarry’s words are a good summation of the constant motion that suffuses The Underground Railroad—a story of those slaves and freedmen whose country allowed them no place of permanent rest.

And of their pursuers. Tracking Cora and her companions from refuge to refuge is the slave hunter Ridgeway, less a character than the grim embodiment of what he calls “the American imperative.” Riding around the country with his scribe, a quisling ex-slave called Homer, he has all the restless mobility of the fugitives he pursues—as though destructive wandering were the common destiny of Americans, imposed on whites, blacks, and Indians by the logic of empire.

Ridgeway’s predations give the novel an unusual, wrenching structure. Each chapter seems like the beginning of a long social novel—the sketch of a community, filled with loves and envies and irreconcilable, dueling dreams. And then it is destroyed, all the latent rivalries, romances, and subtle social entanglements melting in the hot sun of white supremacy. Like Middlemarch, if in every other chapter a character were lynched and the story begun over again. Whitehead replaces the pathos of pain with that of destroyed potential, richly sketched the better to make felt its loss. As though to remind us that the tragedy of slavery was not what happened but what never happened because of it.

There is no great happening in The Underground Railroad, no jubilant event of freedom. What happens, mostly, is that Cora never finds her mother, a woman named Mabel who ran away. The reader is privileged to know her destiny, but Cora isn’t. All she has to remember her by is a tiny vegetable garden, set behind her cabin on the Randall plantation. Cora cultivates this garden, fiercely defending it from her master’s violent favorites, knowing all the while that it will eventually be snatched from her hands.

Like every sanctuary in the novel, it is. And the repetition of this loss leads to a sobering epiphany, when Cora, learning how to read in South Carolina, stumbles over a word: “Cora didn’t know what optimistic meant.” It is a moment of slippage between character and genre—in slave narratives, reading is the manifest, almost theological sign of promised freedom. But it is in reading that Cora, wise in her illiteracy, discovers that the future is not promised to anyone, least of all to those whose country never planned for them to have one.

Voltaire’s Cora, “The Optimist” called Candide, wraps up his bleak romp through the world with a hard-edged, ambivalent commandment. “We must cultivate our garden,” he says to the philosopher Pangloss, who believes that ours is “the best of all possible worlds.” Together, the two have been through a world of misfortune, and when Candide speaks of a garden, it is not a paradise regained that he means. To him as to Whitehead’s Cora, to cultivate our garden means to struggle without hope—to clear the underbrush in a world where no God, no sacred history, no moral arc of the universe has ordained that we are or ever shall be free.

This Issue

September 29, 2016

Maya Lin’s Genius

The Heights of Charm

How They Wrestled with the New