There is a special allure in learning the secrets of people who work behind the scenes, especially when their success—as diplomats, psychoanalysts, or spies—depends in large part on the invisibility of what they do. This is certainly true of book editors. The illusion they seek to promote is that the writer alone has produced the richly textured novel, the pitch-perfect memoir. Robert Gottlieb, now eighty-five and still working, though with a reduced load, at Knopf, where he has had many of his greatest triumphs, pulls the curtain ever so slightly—and reluctantly—aside in his memoir, Avid Reader. “I felt then, and still do, that readers shouldn’t be made aware of editorial interventions,” Gottlieb writes of his early years at Simon and Schuster, when he edited Joseph Heller’s antiwar novel, Catch-22, still his best-known achievement as an editor; “they have a right to feel that what they’re reading comes direct from the author to them.”

Gottlieb has broken his silence, at this late date, for several reasons: the passage of time; the encouragement of his family; the wish to convey certain ideas about editing and publishing; and—perhaps the strongest motivation of all—the understandable impulse to correct the record or settle a score, especially when doing so redounds to his own credit. Who, for example, came up with the title “Catch-22,” when the manuscript, on the verge of publication, was called “Catch-18,” just as Leon Uris’s Mila 18 was announced, mandating a change? Was it because October 22 was, as Heller’s formidable agent, Candida Donadio, let it be known, her birthday? Not at all, Gottlieb says. “One night lying in bed, gnawing at the problem, I had a revelation. Early the next morning I called Joe and burst out, ‘Joe, I’ve got it! Twenty-two! It’s even funnier than eighteen!’”

Gottlieb also wants to inform us about his second career, also mostly invisible, in dance. He first saw George Balanchine’s Orpheus in 1948—“it changed my life”—and calls this early exposure to Balanchine’s art “my great education.” He served for a dozen years as an unpaid programmer, mapping out the season for the New York City Ballet—“a fiendishly complex exercise” in balancing the competing needs of subscribers, dancers, music directors, and choreographers. He describes his relations with Mr. B as “completely impersonal.” He asked Balanchine’s assistant why the great man trusted “the head of a publishing house” to take on such major responsibilities. “It’s your name,” she replied. “Gottlieb [love of god] is the German equivalent of Amadeus. It’s the Mozart connection.” Gottlieb’s late-blooming career as a writer began with dance criticism for the pink-paged New York Observer and a short biography of Balanchine (he later wrote another on Sarah Bernhardt). He has also written an insightful introduction to Kipling’s stories and a book on Charles Dickens’s children, along with many articles for this magazine and others.

The first sentence of Avid Reader sets the tone for the entire book. “I began as I would go on—reading.” Gottlieb’s lonely childhood wasn’t just bookish; it was, as he tells it, pretty much all books. His family of three read at the dinner table and read after dinner. “From the start, words were more real to me than real life, and certainly more interesting.” His distant father was a “hungry and driven (and good-looking)” lawyer from an immigrant family on the Lower East Side; a rare game of chess was “the only activity we shared.” His “gentle and impressionable mother” was a public school teacher in New York. To Gottlieb, they may as well have been Othello and Desdemona: “He didn’t, however, end up strangling her; stifling her naturally gregarious nature was as far as things went.” The violence of the remark takes one by surprise. “Perhaps if he could have brought himself to blame,” Gottlieb wrote of Kipling and his parents, while clearly thinking of his own father, “he would have found it easier to forgive.”

Gottlieb’s favorite characters were “bookish, shy loners” like himself. The zeal for statistics that other boys brought to baseball he brought to books, to the best-seller lists and the selections of book clubs. Heroic acts of reading were young Gottlieb’s way of showing off, including a memorable occasion when he was fifteen or sixteen and raced through War and Peace “in a single marathon fourteen-hour session.” Years later, in college, it was Proust’s turn: “seven volumes, seven days.” “Friends stopped in, food was provided, and I read and read”—the loneliness of the long-distance reader.

In Gottlieb’s account of his college years, we glimpse, among yet more reading, the academic career that might have come of such an obsession. At Columbia he was part of an intense literary circle that included the poet and translator Richard Howard, the poet and critic John Hollander, and Hollander’s future wife, Anne Loesser, niece of the songwriter Frank Loesser and later a well-known historian of clothes. Gottlieb’s girlfriend (and soon wife), Muriel Higgins, another “voracious reader,” was also part of the group. Their snobbishly heady preferences—“Shakespeare, yes; Milton, no. Bach and Mozart, yes; Tchaikovsky, no (that would change)”—were more exciting for Gottlieb than anything he encountered in the classroom.

Advertisement

The “graying” Lionel Trilling, with his “historical/sociological” approach to novels, was a “major disappointment” for Gottlieb, who much preferred “the severe and indignant judgments of Cambridge’s F.R. Leavis.” At Cambridge after graduation, to study at the great man’s feet, he was again disappointed, finding that Leavis, also graying, had entered “his semi-paranoid mode.” Gottlieb was drawn instead into the lively college drama scene, directing avant-garde plays by Beckett and Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral, in a production praised by Stephen Spender. Gottlieb’s early marriage, which produced a child, Roger, foundered in Cambridge and failed in New York, where he worked at Macy’s, in the greeting-cards department, and other dead-end jobs.

Adrift professionally and personally, Gottlieb had his big break at twenty-four, when he was hired at Simon and Schuster, concealing his scorn for the books they published: “They just didn’t live up to my exquisite literary standards.” Simon and Schuster published Dale Carnegie and Calories Don’t Count, but Gottlieb, increasingly powerful in the firm and eventually editor in chief, managed to smuggle in Proust’s Jean Santeuil and the experimental novels of Michel Butor. Catch-22 was a career-making success for a young editor of twenty-six, along with the “superior popular fiction” that became his specialty.

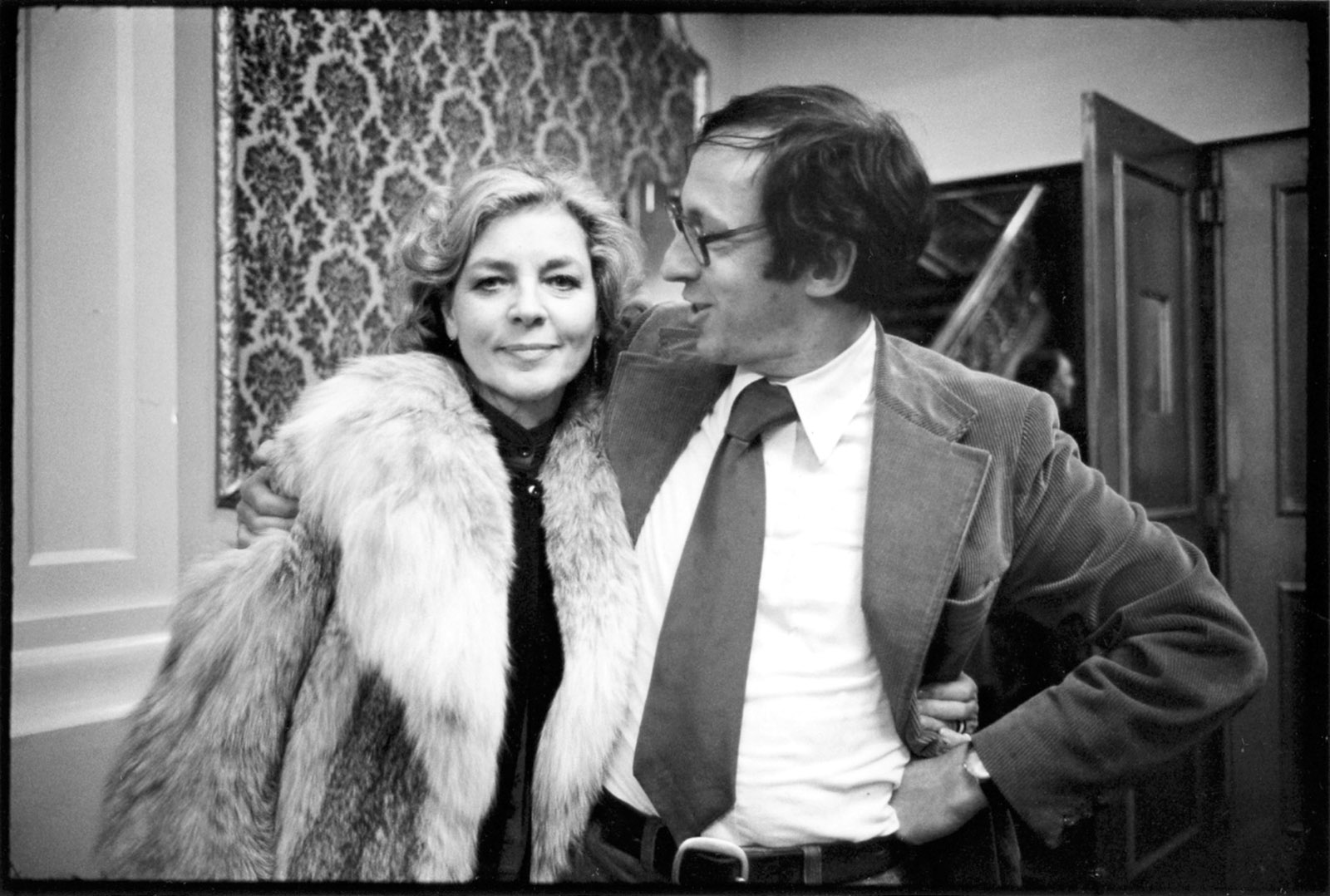

Gottlieb calls the period between the mid-1960s and the early 1970s “the great hinge in my life.” His parents died; he embarked on a new, happy marriage to the actress Maria Tucci (daughter of the Italian writer Niccolò Tucci, whose stories Gottlieb had edited), with whom he had two children; and, restless with the sheer ease of life at Simon and Schuster, he accepted an offer to run Knopf, the “great literary house of the century,” where he remained for nearly twenty years. Random House had bought the firm, with its formidable list that included Thomas Mann, Gide, Kafka, and Cather, as well as such reliably lucrative properties as Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet (four hundred thousand copies a year), “but didn’t know what to do with” it. “Avid Reader to Head Knopf” was the headline of one news story.

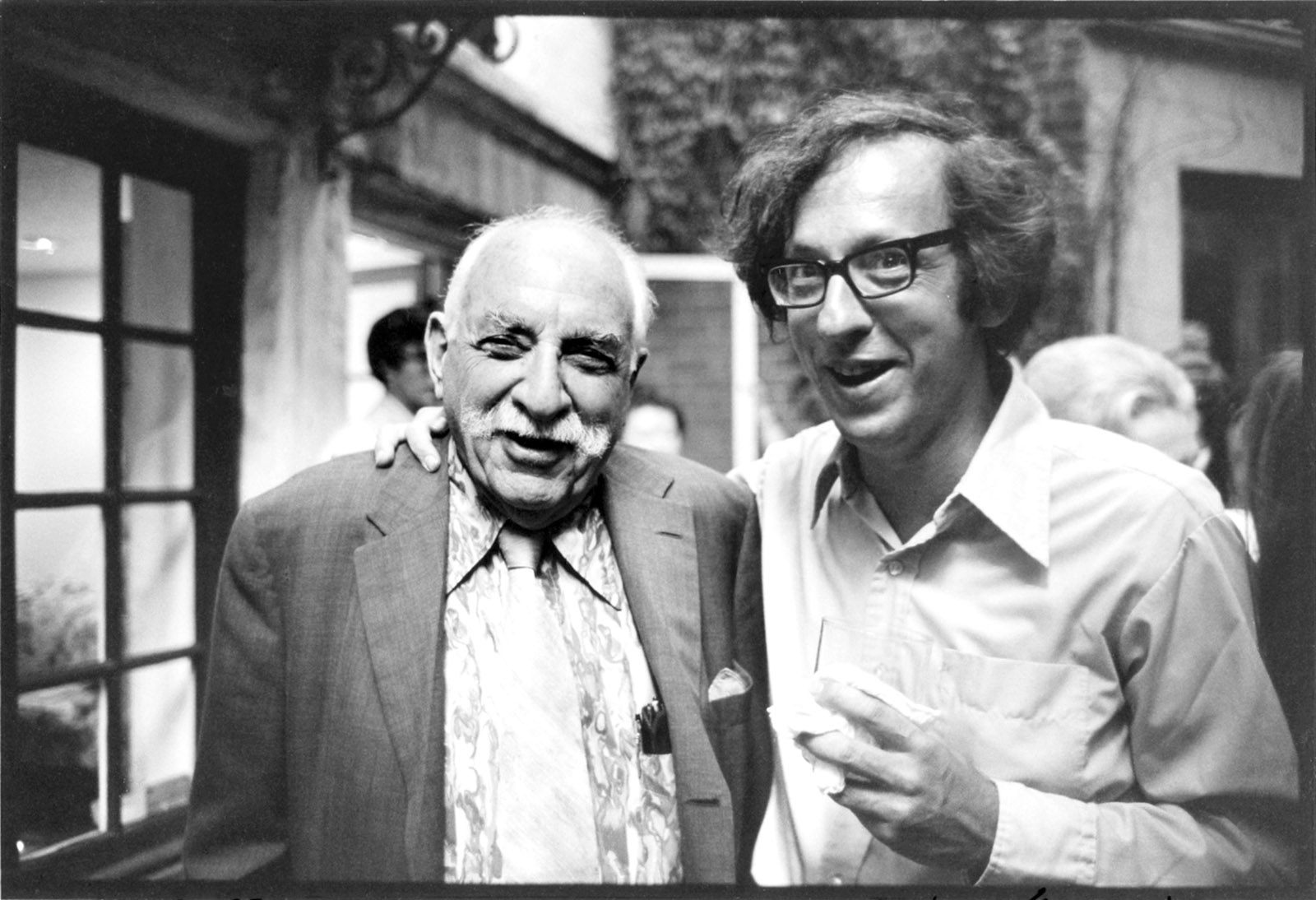

What Gottlieb found at the firm, with Alfred Knopf himself deposed but still hovering in the office, was a “gentle desuetude” and pervasive “low-level depression.” He simplified procedures, eliminated time-wasting rituals (the martini lunch), and hired gifted editors. The result was an intimidating list of successes, to many of which he devotes a succinct paragraph or two, sometimes in adjective-heavy language that resembles the catalog copy he himself wrote over the years. Again, the emphasis is on heroic acts of reading: essentially rewriting, with Carol Janeway, the immense German submarine thriller Das Boot; quarrying the three to four million words of John Cheever’s tiny notebooks for the triumphant The Journals of John Cheever, a feat worthy of Max Perkins; going through Robert Caro’s immensely detailed biographies of Robert Moses and LBJ sentence by sentence, summed up by what could be the first line of a villanelle about editing: “He felt I was being insulting, I felt I was doing my job.”

There were his Nobel Prize winners. Toni Morrison needed little hands-on editing. “Our only real disagreements have to do with commas, since she hates them and I love them.” But it was Gottlieb who persuaded her to quit her own editing job at Random House and devote her full attention to writing. It was Gottlieb who read the opening section of what was to be a three-part historical epic and told Morrison, “Stop here. This is the novel.” The novel was Beloved. Doris Lessing needed editing, in Gottlieb’s view, but refused to take his advice. “One of our running jokes—it ran on for decades—was that I claimed she never took any of my editorial advice while she claimed she took all of it.” V.S. Naipaul, “a superb writer” and a snob, “didn’t welcome editorial suggestion, and fortunately didn’t need it.”

Salman Rushdie won the Booker Prize for Midnight’s Children, but Gottlieb, who also published Shame, found Rushdie “more demanding, less cordial” after his big success. In 1993, both attended the English premiere of Michael Berkeley’s opera Baa Baa Black Sheep, where Rushdie complained about the bother of restrictions imposed on him by the British police, who were protecting him after the ayatollah’s fatwa:

Advertisement

Embarrassed, I tried to change the subject by commiserating with him over the fact that if he had only known in advance what was going to happen, he could have dropped or changed a few lines in The Satanic Verses, saving the lives of the people who were assassinated [Gottlieb means the Japanese translator; the Italian translator and a Norwegian publisher were also attacked] because of their professional involvement with it. In a fury he turned on me, sputtering, “Why would I have done that? It’s not my fault that they were killed!”

I would have welcomed a bit more about the opera, with its libretto by David Malouf. It is based on a traumatic (and autobiographical) childhood tale of Kipling, whose life and words have been of interest to both Gottlieb and Rushdie.

Among Gottlieb’s other big successes at Knopf were celebrity memoirs by Lauren Bacall (who wrote her book holed up in a Knopf office), Katharine Graham, and Bill Clinton. He recounts his work with them with zest and telling detail. “Left-handed Clinton scrawled on big yellow legal pads, his left arm curved up and around and then down to the page—painful to watch, and more painful to try to decipher.” Gottlieb mainly suggested cuts to Clinton’s exuberant performance. “This is the single most boring page I’ve ever read,” he wrote in one margin. “No, page 511 is even more boring!” the former president responded. When Hillary was present during Gottlieb’s “forays to Chappaqua,” he found her “a friendly presence, and it was interesting—and touching—to see how much he valued her opinions and responded to her reactions.”

About the political views of Graham and Clinton and the attacks on them, Gottlieb has little to say. His editorial philosophy comes across most clearly in his comments about editing “genre” books—the spy thrillers of John le Carré and Len Deighton, the sci-fi best sellers of Ray Bradbury and Michael Crichton—a field in which he has excelled. Working with the circumspect le Carré—another man experienced in maneuvering behind the scenes—made Gottlieb feel that he “was in a spy story”: “It was just his nature to be wary, to be one step ahead of the game, even when there was no game.” Prodded for a fuller characterization of Connie Sachs, the aging spymaster, le Carré “couldn’t wait to get back to her, and in a week or so I had twenty or thirty terrific new pages.” Their friendship frayed when Gottlieb questioned a description of a couple at a restaurant as “Jewish-looking,” pointing out that “Jews didn’t have a ‘look’”; after much resistance, le Carré, “not anti-Semitic, far from it,” agreed to a small change.

Deighton, by contrast, regarded editorial advice as something like dental surgery, to be gotten over as quickly as possible. When Gottlieb pointed out that a minor character killed off early on in a novel reappeared, in good health, a hundred pages later, Deighton promised to deal with the problem. “Now on page 49 this character was ‘shot and almost killed.’”

Gottlieb’s brilliance as an editor comes across in his seemingly unerring sense of what can and cannot be done. Crichton knew everything about science and plot but had no feel at all for character. “What Michael wasn’t was a very good writer.” Another editor might have taken the manuscript of The Andromeda Strain and tried to suffuse its wooden characters with personality quirks. Not Gottlieb:

It occurred to me that instead of trying to help him strengthen the human element, we could make a virtue of necessity by stripping it away entirely; by turning The Andromeda Strain from a documentary novel into a fictionalized documentary.

A larger principle is at work in this brilliant decision. After criticizing one of the Knopf editors he hired, Gordon Lish, for his “profound need to put his imprint on fiction—to steer his writers toward his own aesthetic,” most famously (and controversially) in the case of Raymond Carver, Gottlieb remarks:

As I’ve tried to drill into countless aspiring editors, the most damaging thing an editor can do to a writer is to try to change a book into something other than what it is, rather than try to make it a better version of what it is already.

At The New Yorker, another legendary enterprise that had, as he describes it, fallen into desuetude and depression, Gottlieb tried to adopt the same principle of making a better version of what it was already. Again, as at Knopf, there had been a change of ownership, after Si Newhouse’s Condé Nast had acquired it. Again, as at Simon and Schuster, Gottlieb was restive, eager for a change of scene:

I told him [Newhouse] that I revered what The New Yorker was and didn’t want to see it change into something different; that I thought it needed new energy, but that I was a conserver by nature, not a revolutionary, and that if he wanted a different magazine from the one he had, I wasn’t the person for the job; that I felt I could make it a better version of what it was, not turn it into something it wasn’t.

Gottlieb concedes that he “curated” the magazine “as if it were a weekly anthology rather than concerning myself with its overall editorial development.”

Feeling that the magazine had “lost its edge,” Gottlieb pursued “new writers and sharper art.” His redesign of parts of the magazine, such as “Talk of the Town,” was widely admired, and he brought brilliant fresh writing to the magazine, especially among reporters; he mentions Alma Guillermoprieto (writing about Latin America), Mark Danner (Haiti and the Gulf wars), Julian Barnes (writing from London), and Joan Didion (from California). “The last new reporter I welcomed to the magazine was David Remnick,” he writes, “whose writing from Russia in The Washington Post I greatly admired.” This “turned out to be the most fortunate hire of them all.”

Gottlieb is widely seen as supplanting one great editor, William Shawn, and preparing the way for another, David Remnick, with the shock-and-awe interregnum of Tina Brown in between. In Avid Reader, he takes potshots at all three of them. Shawn was, he says, less revered by his writers than many claimed publicly. Tina Brown, the firebrand Gottlieb refused to be, “changed it overnight from a magazine about its writers to a magazine about its subjects. And David, with his background as a journalist, has seemed comfortable with that new direction.”

Is this fair? As evidence, Gottlieb recounts his own experience with Remnick as editor, after Gottlieb had been asked to leave by Newhouse and then returned, as an “invisible” editor, to Knopf, which Newhouse also owned at the time. Gottlieb had proposed a story about Minou Drouet,

a now-forgotten French literary phenomenon of the fifties, a little girl of eight…who became a bestselling poet and the subject of a torrent of humiliating publicity when half the Paris literary establishment insisted that it was her mother who had actually written her poems and the other half defended her with equal vehemence.

Remnick, Gottlieb claims, didn’t understand the appeal of the story—“Minou Drouet wasn’t a natural subject for the magazine, and there was no hook”—but went along with it anyway, out of professional courtesy to Gottlieb.

In order to research the piece, Gottlieb and a friend tracked down Drouet’s house in Brittany and saw “a handsome middle-aged woman emerge and go into her garden.” And then? “Rather than intrude on her privacy, we slunk past.” Remnick was puzzled by this decision. “That’s what I don’t understand,” Remnick said to Gottlieb. “You were there. You saw her. Why didn’t you knock on her door and talk your way in? That’s what reporters do!” To which Gottlieb replied—triumphantly in his own mind, but lamely, it seems to me—“But I’m not a reporter.” Is the distinction between writing and reporting really so clear? And why assume that Drouet, after all these years, would have preferred privacy to the attention of a sympathetic journalist?

Given Gottlieb’s own instinct for privacy, it is not surprising that the writing of Avid Reader did not always come easily. For “at least twenty years,” Gottlieb says, he resisted the idea. “I specialize in holding my feelings in,” he confesses, describing himself as “emotionally unforthcoming.” Only on rare occasions, as in his account of the difficulties he encountered during the early years of raising a child with Asperger’s syndrome, does he allow himself, briefly, the kind of self-exposure many readers have come to expect from many memoirs; despite his disclaimers (“I couldn’t believe the world was waiting for an account of my exploits”), his is a celebrity memoir, though a somewhat veiled one. “I was always urging him to dig deeper,” he writes of the choreographer Paul Taylor. It’s easy to imagine an editor asking the same of this memoir.

In an autumnal final chapter, titled “Living,” Gottlieb seems to have reached a sense of acceptance of his record of conspicuous success and his occasional failures. He now divides his time (lucky man!) among apartments in New York and Paris and a house in Miami Beach, where he advises the Balanchine-loyal Miami City Ballet. He edits just one novelist, who happens to be exactly his own age: Toni Morrison. The lonely, bookish only child, who loved characters like Mowgli for finding ways to be “embedded in a family not his own,” has found many “families I’ve created or helped create” in the camaraderie of publishing offices, dance companies, and close friends. After years of psychoanalysis and monitoring of his own skills as a parent, he has even reached an accommodation with his own father. “Your father is your father.”

Recently, as Gottlieb found himself starting “to recede from whatever limelight I had once been in,” he came upon a tercet from Robert Frost’s dark poem “Provide, Provide”:

No memory of having starred

Atones for later disregard,

Or keeps the end from being hard.

Gottlieb’s response is disarming. “I never felt I was a star. I don’t now feel disregarded. And, yes, the end may very well be hard, but perhaps fate will be kind, and at least let me keep on reading for a while.”