In December 2016, big billboards go up in Charleston that show an AR-15 assault rifle with a red bow tied around it and the line, “All I want for Christmas is You.” A gun store is pushing its Blackhawk brand military weapons.

Guns are embedded in South Carolina culture, with every attempt at firearm regulation trampled by the state legislature. Fathers give their sons, and some daughters, guns in rites of passage. A ceremony that survives is the first-blood ritual for adolescent hunters: a boy accompanies his father on a hunt and washes himself in the blood of the first deer he kills.

Dylann Roof got his gun. His father gave him money for it on his twenty-first birthday. “Happy Birthday! Here is $400 for the gun and the concealed carry permit,” the card read.

I went to the gun warehouse that advertised AR-15s to see the pistol Roof used for the massacre of nine African-Americans at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in June 2015. Palmetto State Armory, in the Charleston suburb of Mt. Pleasant, is the size of a big box store. It was previously a supermarket. (The company’s motto, on its logo, is Desperta Ferro—“Awake the Iron.”) The idea that a young man shops for guns in a 40,000-square-foot store with Van Halen playing on the ceiling speakers is, in this part of the US, unremarkable.

In the middle aisles are ammunition, gun sights, accessories, gun cases, and targets—bull’s-eyes, plus targets in the shape of men, like a guy in a hoodie. On the left side of the store are racks and racks of rifles, shotguns, and assault weapons, propped like rakes, by the hundreds. And in dozens of locked glass cases, like jewelry, the handguns.

I walk along one hundred yards of glass cabinets, past the Smith & Wesson case, the Browning case, past Springfield, Sig Sauer, Kemper Pistol, Uberti, Baer, Beretta, and arrive at the Glocks: engineered in Austria, manufactured in Marietta, Georgia. Roof used a Glock 41, a .45 caliber gun that feels like artillery in the hand—black, nine inches long, thirty-six ounces loaded.

“That’s the big daddy,” says the salesman, “for target and home defense. Holds thirteen rounds, strong recoil.” The salesman is a small man with a tenor voice, which he throws an octave lower to assist in male bonding. “I have a Glock 36”—he pulls back his jacket to show the holstered gun—“smaller, better for concealed carry.”

Roof added a laser sighting to his Glock, which throws a red dot where the shot will land, and he used hollow point bullets. Hollow points are more lethal. When one hits a person, body fluids enter the tip and cause the metal slug to spread and deform into a spiked wheel, which continues to progress, shredding internal organs. They cost about seventy-five cents each, twice the cost of a standard bullet.

The ammunition aisles are like a cereal section, a colorful array of boxed rounds. I walk the hollow point row, past the brands Civil Defense, Remington, Fiacchi, Mag-Tec, Sig Sauer, Federal, Gold Dot, Winchester, and RIP (“Radically Invasive Projectile”). Roof bought Winchester.

Felicia Sanders’s testimony at Roof’s trial gives way to crime scene evidence (police body cameras, ballistics, photos of the dead). Half a dozen FBI and state investigators testify, as well as the pathologist who performed the autopsies (fifty-four bullets removed). Surveillance cameras from Walmart capture Roof buying extra hollow points. Selfie videos taken by Roof show him practice-shooting in the backyard—bottles, tree stumps, a phone book. Maps made from GPS data track the killer’s movements, from the plantations, to the church, and to escape in North Carolina. And there’s the two-hour confession made to the FBI.

“Are you a neo-Nazi?” asks FBI agent Michael Stansbury, interrogating on camera, sixteen hours after the shooting.

“No because you have to be part of a movement,” Roof says. His high, hoarse voice is flat, affectless. The confession tape continues:

Stansbury: Are you a white nationalist?

Roof: I am a white supremacist. We are superior to blacks. Only East Asians are equal to white people, Chinese and Japanese.

Stansbury: What happened last night?

Roof: Well, I did, I killed them.

Stansbury: Why?

Roof: I had to do it, because somebody had to do something. Black people are killing white people every day on the streets, and they rape white women, a hundred white women a day. The fact of the matter is what I did was so minuscule to what they’re doing to white people…. There’s no KKK left. The KKK never did anything anyway. I’m glad I did it.

Stansbury: Why did you choose Charleston?

Roof: I like Charleston…it’s really nice down there. It’s a historic city, and at one time, it had the highest ratio of black people to white people in the whole country, when we had slavery.

Stansbury: What made you think this way?

Roof: The first thing that woke me up was the Trayvon Martin case. I kept hearing about this kid, and for some reason after I read an article I typed the words “black on white crime” into a search. And that was it. Ever since then.

Stansbury: Was it just you, or was there someone else?

Roof: Just me, and the Internet.

Trayvon Martin, the black seventeen-year-old killed by the white vigilante George Zimmerman in Florida in February 2012, started Roof on his journey into “totally aware” supremacy. When he searched “black on white crime,” the first pages he landed on belonged to the Council of Conservative Citizens.

Advertisement

The webmaster of the Council of Conservative Citizens is nearby. Kyle Rogers, forty-one, is an ideologue who lives twenty miles north of Charleston, in the town of Summerville. He feeds supremacist bile into the pipeline of the Internet from his ranch-style two-bedroom house. I ring the bell, but no one answers, despite cars in the driveway and lights on. I come back the next day, the same outcome. I write letters, telephone, and send e-mails. No reply from Kyle Rogers. A lesson is that supremacists are happy with Internet anonymity, but face-to-face conversations, and the public avowal of their supremacist faith, frighten them.

Since Roof was arrested, the Council of Conservative Citizens (founded in 1985, membership unknowable, but possibly five hundred) has melted into a site called Conservative Headlines. It contains the same sort of material Roof stumbled on (“soulless, evil, jungle beast feral colored boy in black on white stomp”). The poisonous hectoring of groups like these calls into question the idea that Roof was “self-radicalized,” to use the cant of terrorist politics. Was he not armed by an ideology he encountered from these teachers? Conservative Headlines offers fealty to the new White House, and heaps praise on its chief strategist, Steve Bannon, the idea man who works with President Trump.

The path of Dylann Roof’s “enlightenment” is shadowy, but the shooter’s house is known. There are still cotton fields near Eastover, Roof’s hometown in Richland County. The fields are brown and cut to stubble for winter, with white cotton tufts on the ground. Black hands no longer pick it, machines do, and black people have been leaving the rural South for a hundred years. Yet the middle of South Carolina is as black as any place in the country, with African-Americans composing nearly 50 percent of the population.

On the two-lane blacktops that lead to Dylann Roof’s home—one is called Old Chain Gang Road—you see a trailer, a wood cottage, a sofa dump, a railroad track, a country church, a deer stand, a ranch house, a trailer, and an eighteen-wheeler parked in a yard. Hunting is important here, and churches. Congaree Baptist Church, Pleasant Grove Baptist, and Red Hill Baptist all stand within one mile on the same road. Pickup trucks are important. White country music, as well as black gospel, is important.

Roof lived at 10428 Garners Ferry Road, a fake log-cabin bungalow with a big front porch and the flag of Clemson University hanging from the front. A man pulls up in a gray pickup. He is about sixty, gray hair, skinny nose, weathered face, and he looks up from lidded eyes. It is Dennis Beard, Dylann Roof’s stepfather, who came to the trial with Roof’s mother. He goes inside; it is his house.

I knock, and Dennis Beard appears behind a screen door.

“What’s the problem?”

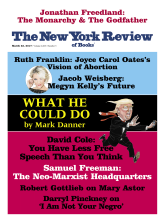

“I write for this paper”—holding up The New York Review of Books—“and I want to talk about the trial.”

“Go right home to where you came from! Get off this property now!”

“Is Ms. Amy Roof—”

“I said now! Or I’m gonna let the dogs out on you!”

A red shed stands near the house. Here, Roof made movies of himself test-firing the Glock. In one video, he wears a Gold’s Gym tank top, pajama bottoms, and aviator sunglasses. The gun blasts a red flame from its nose, recoils, kicks him backward. Roof’s face has an odd, droopy lip. I look around the shed. The targets and casings have been cleared, but bullet holes spray the bark of a loblolly pine tree.

Another survivor of the massacre provides the climax of the case. Seventy-year-old Polly Sheppard (“Miss Polly”) is a careful storyteller in the witness chair, softspoken to the point of inaudibility, as she dutifully recounts the night.

“The defendant said to me, ‘Have I shot you yet?’ I was lying under the table, praying aloud. I said, ‘No.’ He said, ‘I won’t shoot you because I want you to tell the story.’”

Advertisement

Ms. Sheppard is one of the victims who does not want the death penalty—in fact, she did not want the trial. And yet she gives the prosecution its crescendo, and another afternoon of tears. As she steps down from the witness box, all in the courtroom rise to their feet, as at a benediction.

On December 14 the jury goes out, and two hours later the twelve return. The foreman, a white man in his fifties wearing tortoiseshell glasses, gives the verdict—guilty on all thirty-three counts.

Judge Richard Gergel suspends the trial for Christmas and Hanukkah, and, after the New Year, resumes with the penalty phase. The jury must decide: life in jail without release, or death.

Roof represents himself for these final days, having supplanted his lawyers by prior arrangement. The prosecution brings to court twenty witnesses, family members of the dead, for “impact testimony,” memorializing those killed, using witness trauma to make the government case for death. Roof asks no questions and introduces no evidence. His now-former attorney, David Bruck, and two other lawyers, sit with him. As his standby counsel, they are barred from speaking or raising objections, and instead they scribble Post-it notes to their former client. Roof remains preternaturally passive.

To show “malice aforethought,” which is necessary to the murder charges, the prosecutor, Assistant US Attorney Jay Richardson, introduces the “jailhouse manifesto.” Roof tries to stop it, briefly objecting, then returns to silence.

The day before the end, Roof’s father, Franklin “Benn” Roof, turns up, heavyset, age fifty-three. Benn Roof and Dylann’s mother, Amy, have not lived together in twenty years; they separated around the time Dylann was born. Benn Roof has a construction business. He also cuts yards, and before the murders it was he who gave Dylann one of the only jobs he had, cutting grass. With thinning gray hair, jowly cheeks, and a blue suit, the elder Roof wears a blank expression and, like his son, appears emotionless. He has declined to speak to the press since the week of the crime, in June 2015, when a newspaper published a photo of him in his yard at home—shirtless and heavily tattooed, wearing his apparently customary two nipple rings.

It is on the day his father comes in that the defendant does something that will guarantee a death sentence. He wears a pair of white sneakers—prison shoes, issued in jail—that he has decorated with his favored German signs. From the witness stand, FBI agent Joseph Hamski points out the Nazi symbols. On Roof’s feet are the Odal rune and the Lebensrune, with SS bolts. Few but the judge and jury can see, but at this disclosure there is an audible change of tone, and the courtroom is stunned. The decorated shoes, worn in the presence of a room of victims, do not suggest either a change of mind or the possibility of remorse—the two conditions for mercy, under the law.

On the last day of the trial, January 6, Richardson delivers a two-hour closing statement, the government’s call to death. He calls Roof’s crime “a modern-day lynching,” using the radioactive word for the first time, recalling the nearly five thousand mob killings during the Jim Crow era. Richardson does not use the word “terrorism,” although the massacre fits the description.

Dylann Roof stands to speak. His voice sounds chalky, as though powder lines his throat:

It’s safe to say that no one in their right mind wants to go into a church and kill people. In my confession I said I had to do it. Obviously that is not true. What I meant was I felt like I had to do it, and still do feel it…. You could say, of course, that everyone hates me. I’m not denying that. In my mind, everyone who hates has a good reason. But sometimes they are misled…. But anyone who thinks I am filled with hatred has no idea what hatred is. They don’t know what real hatred looks like…. I have a right to ask you to give me a life sentence. I am not sure what good that will do. I know that only one juror has to disagree with a death penalty.

The statement lasts seven minutes, with pauses. As he speaks, Roof refers to a piece of paper on a lectern in front of him and purses his lips hard. He is possibly the only one in the courtroom who has not wept. He looks at the jury blankly, and then down at his paper, and then sits down.

The jury is sent out at about 1:00 PM, and three hours later, they file back in with the sentence. It is life in prison without release on fifteen charges. It is execution for each of the other counts—nine victims, according to two different statutes—eighteen death sentences.

USA v. Dylann Storm Roof does not demonstrate that violent racism is a mental illness. It implies instead that white supremacy is like a root system that occasionally produces an extreme growth. The trial shows that supremacy is a story of ideas and tribal ethnicity, not one of pathology.

Roof’s defense lawyers, until he sidelined them, saw an argument for mental illness as the way to keep their client from execution. Before the trial and against his wishes, they moved for a competency examination. Eight psychiatrists and psychologists spoke at the closed hearing, and Judge Gergel studied a dossier of written evidence. He ruled Roof capable of standing trial but sealed the reports. Following conviction, the defense moved for a second competency hearing, which took place on a weekend in early January. The court again ruled Roof capable and again sealed the results. Two weeks after the trial, Judge Gergel unsealed case filings that contained a sentence here and there on the two mental exams, while still withholding the reports.

It must be said that paid mental health experts possess an incentive to call a defendant mentally ill. And further, an hour or two with a patient does not open a royal road to his unconscious. Nevertheless, Dr. James Ballenger, a forensic psychiatrist, thought that Roof showed symptoms of “Social Anxiety Disorder, a Mixed Substance Abuse Disorder, a Schizoid Personality Disorder, depression by history, and a possible Autistic Spectrum Disorder,” according to a court filing.

It would be reassuring to whites to believe that a person like Dylann Roof is disturbed or crazy. Yet what if he is not? “Schizoid personality disorder” is not schizophrenia, and it involves no hallucinations or delusional beliefs; it is a condition of distance or detachment from social relationships—an odd determination, considering Judge Gergel’s finding that “Defendant was extremely engaged during his two-day competency hearing.” At different points in the trial, evidence suggested Roof’s social anxiety, recreational drug use, and depression. These unsurprising facts place him squarely in a giant cohort of late adolescent men. One defense filing put things as vaguely as possible: “A twenty-one-year-old’s brain is still developing, making a person of that age likely to be more impulsive and more vulnerable to outside influences.”

A day or two of observing Roof is enough to suggest that he lives somewhere on the autistic spectrum (while not too far along that continuum). Yet he addressed the court several times, stood to make objections, and interacted with counsel and judge. Roof possesses calm and little emotion of any sort. What is oddly missing from him is hatred in its hot form. His lawyer David Bruck referred to “perseveration” in one statement, a psychiatric term describing fixation and repetitive responses, before he was stopped by the judge for bringing up Roof’s mental health, in disregard of the finding of competence.

It is a fallacy to see USA v. Roof as a case of psychopathology. It cannot be a surprise that someone these days would become intoxicated with race identity, especially whiteness and blackness, whose extreme advocates travel the Internet. Dylann Roof had no social group, no face-to-face political affiliation. He sat in a room for five years, with little human contact, and absorbed from the Internet the story of the final race conflict, the glories of white identity, and the war of all against all, ideas that appear on websites like Stormfront, White Information Network, Occidental Dissent, American Renaissance, Traditionalist Youth Network, and League of the South.

In the US, suffused as we are with the inheritance of slavery, and with the ubiquitous ideology of racial difference, it stands to reason that a young man might use whiteness to fuel his fantasy life. That absolves no one of the responsibility. It certainly does not absolve the people who write about apocalyptic whiteness on the Internet, so that a kid is seduced by it. To dismiss the Charleston massacre as a case of mental illness or an idée fixe does not explain anything. Look instead at the soil, in the root system of white supremacy.

The Council of Conservative Citizens denounced Roof’s act while pointing to “legitimate grievances.” But USA v. Roof may actually strengthen the cause of white supremacy. We are in a cultural moment in which white entitlement has surfaced as a mainstream goal. In Dylann Roof you have vicious white supremacy, and its very viciousness makes things short of it appear more reasonable.

After the trial, I go back to Emanuel A.M.E., the two-hundred-year-old organization that the killer shot to pieces. The stuccoed brick church can seat five hundred, with pews in a large balcony. On the Sunday after the verdict, 150 come, twenty-five of them white, something new for the congregation. Some of the family of the dead are here, and the decent thing is to leave them alone.

A thirty-voice choir wears burgundy robes and sings to accompaniment from an electric piano, a drum kit, and a brass player, who improvises on a flugelhorn. Half of the two-hour service is danceable.

Reverend Eric Manning, taut and composed, speaks in restrained tones, until he mounts the pulpit. Within five minutes Manning has raised the pitch, moving the room to relief and gratitude.

The text on which his sermon is based is “Great is thy faithfulness,” from Lamentations, Chapter 3. “I know what you’ve been going through this week, with the trial, and I want to share how it is you are able to come here this day. The answer the benefit of praising God. Who we know holds our future, and who has brought us a long way.” Reverend Manning mops himself with a towel.

“You can wonder, with this trial, has God forsaken me? But even this week, I came out of the courtroom saying, great is thy faithfulness.”

There are eight ushers, women who wear long-sleeved, navy blue dresses. They cover up from the neck to the knee, and the women have on bright white gloves. The ushers move up and down the aisles, minding when someone needs attention. I see one of the survivors of the massacre, “Miss Felicia” Sanders, among them.

—This is the second of two articles. Research was supported by the Nation Institute.