You see her from a distance, at the end of a long enfilade of rooms. As you approach, you notice that she is already turned toward you. She is in her fortified underwear: a light blue bodice, white slip, light blue stockings; in her raised right hand, a powder puff like a vast carnation. To the left, over a chair, is the blue dress she will soon put on. To the right, though you might not at first observe him, is an impatient, mustachioed figure in evening dress, his top hat still—or already—on his head. But once again, you are aware that she has eyes only for you.

She is Manet’s Nana, in the Hamburg Kunsthalle, benefiting from a recent rehang that makes her even more of a cynosure. Nana is the courtesan protagonist of Zola’s 1880 novel of the same name, and you might reasonably assume that Manet’s painting is, apart from anything else, one of the great book illustrations. But it is more interesting than this. Nana first appeared as a minor character in Zola’s L’Assommoir (1877). Manet spotted her there, and painted his portrait of her. When Zola saw it, he realized that, yes indeed, she was worth a novel in her own right. So, far from Manet illustrating Zola, what actually happened was that Zola was illustrating Manet.

The close friendship, interaction, and parallelism between writers and artists in nineteenth-century France are the subject of Anka Muhlstein’s The Pen and the Brush. Balzac put more painters into his novels than he did writers, constantly name-checking artists and using them as visual shorthand (old men looked like Rembrandts, innocent girls like Raphaels). Zola, as a young novelist, lived much more among painters than writers, and told Degas that when he needed to describe laundresses he had simply copied from the artist’s pictures. Victor Hugo was a fine Gothicky-Romantic artist in his own right, and an innovative one too, mixing onto his palette everything from coffee grounds, blackberry juice, and caramelized onion to spit and soot, not to mention what his biographer Graham Robb tactfully terms “even less respectable materials.”

Flaubert’s favorite living painter (also that of Huysmans’s Des Esseintes) was Gustave Moreau, and his Salammbô is like a massive, bejeweled, wall-threatening Salon exhibit—this being both the novel’s strength and its weakness. Baudelaire, Zola, Goncourt, Maupassant, and Huysmans were excellent art critics (Monet thought Huysmans the best of all). The subject is enormous, and might threaten to go off in every direction. What about photography? And book illustration? And sculpture? What about poets and pictures, both real and imaginary? Anka Muhlstein wisely limits herself to prose writers, and to five who speak to her most clearly: Balzac, Zola, Huysmans, Maupassant, and—a slight chronological cheat—Proust. The result is a personal, compact, intense book that provokes both much warm nodding and occasional friendly disagreement.

Of all the arts, writers most envy music, for being both abstract and immediate, and also in no need of translation. But painting might come a close second, for the way that the expression and the means of expression are coterminous—whereas novelists are stuck with the one-damn-thing-after-another need for word and sentence and paragraph and background and psychological buildup in order to heftily construct that climactic scene. On the other hand, it is much easier for writers (and composers, for that matter) to work in subtle, or not-so-subtle, homages to other art forms than it is for painters. Thus Zola gives a friendly nod to Manet in his novel Thérèse Raquin, where a murdered girl in the morgue is described as resembling a “languishing courtesan” offering up her breasts to us, while the black line around her neck (evidence of strangulation) recalls the black ribbon around the neck of Olympia; just to confirm the homage, Zola also includes that rather sinister black cat from the painting.

Zola’s public support for Manet and the Impressionists was loud and vigorous, and came at just the right time. (Sometimes there seems to be a logical assembly of rallying forces, at others it is a matter of fortune. When Tom Stoppard spoke at Kenneth Tynan’s funeral, he addressed the critic’s children on behalf of his own generation of playwrights: “Your father,” he told them, “was part of the luck we had.”) Manet certainly expressed his—equally public—gratitude to Zola, painting a celebrated portrait of the novelist at his desk: pinned on the wall behind is a print of Olympia, and clearly visible on the desk is Zola’s pamphlet in praise of the painter. Zola was a forceful, detailed, and brightly colored critic, though he didn’t exactly deal in the quiet hint; art was there to describe and to change society—both his and its functions were combative. If the aesthetic argument shaded into the political, so much the better.

Advertisement

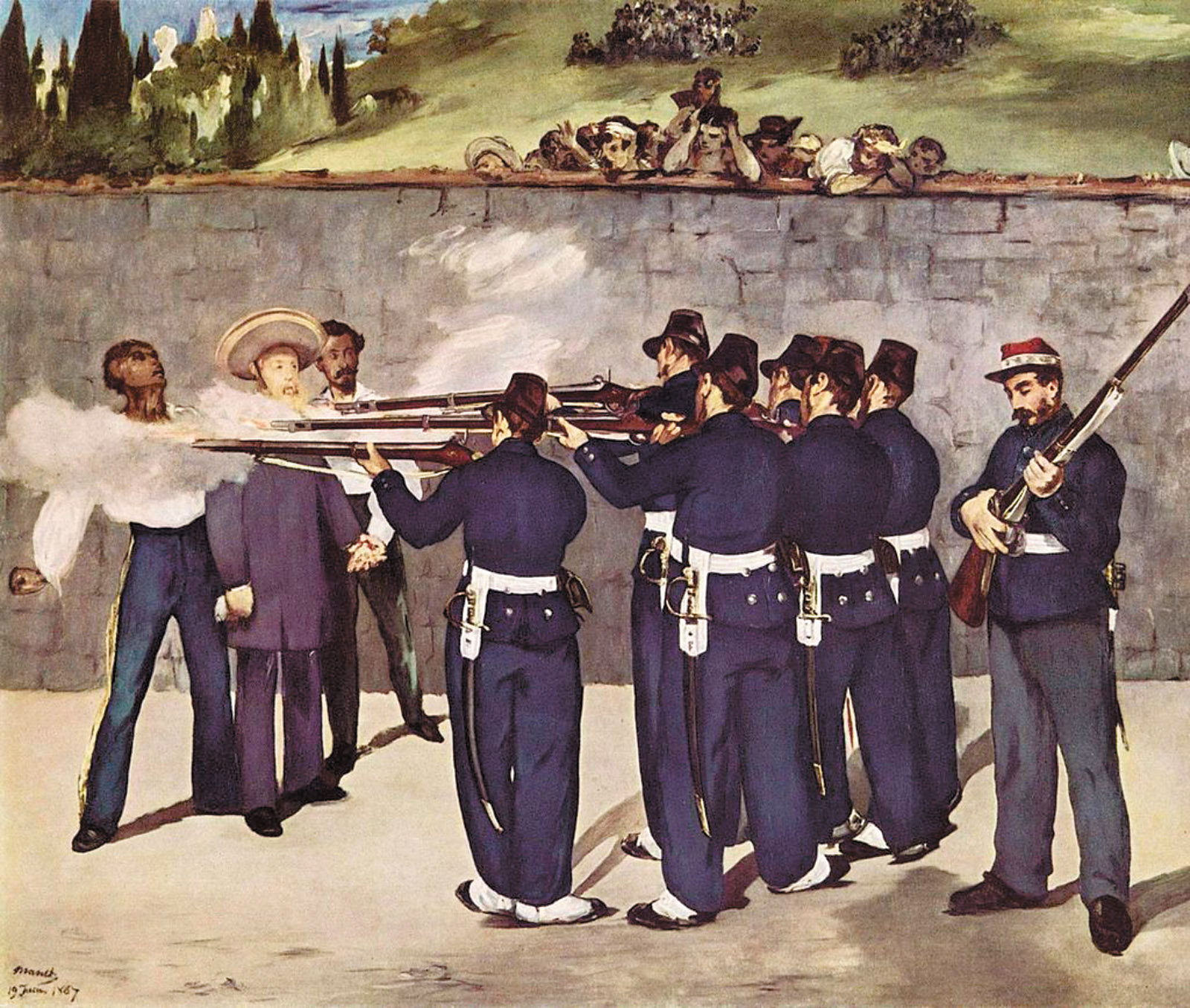

And Zola could be just as keen on having things both ways as his opponents were. In 1869, when Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian was about to be translated into mass-media form as a lithograph, the authorities banned it. The reasons were clear: the event was a key moment of geopolitical humiliation for Napoleon III’s regime, in which France had abandoned its Mexican puppet to his fate. Zola, in an unsigned article in La Tribune, piously claimed (as had Manet) that the picture was totally nonpolitical, with the subject treated “from a purely artistic point of view.” When this didn’t work, four days later he was pointing out the opposite: the “cruel irony” of Manet’s picture, which could be read as “France shooting Maximilian” (see illustration on page 26).

So there was allusion, name-checking, and boosterism, either discreetly worked into fiction or overtly shouted from newspapers. Balzac’s treatment of painters, as Muhlstein points out, is much more admiring than his treatment of his fellow writers. Whereas Daniel d’Arthez, the most significant writer he invented, is “a cold, gray, virtuous character…all his painters are jolly, attractive, unpredictable, and often practical jokers.” This hardly applies, however, to the Balzacian painter who made the most impact on real-life artists: Frenhofer, the protagonist of “The Unknown Masterpiece.”

This twenty-page text sets the fictitious Frenhofer (elderly, so inevitably like “a Rembrandt”) against the established, middle-aged Pourbus—court painter to Henri IV—and the aspiring young Poussin. Frenhofer, sole pupil of Mabuse, is the driven genius with impossibly high standards to whom the others defer; for ten years he has been secretly working on a portrait that expresses all he has learned about art. Poussin gulls him into showing it, whereupon the supposed masterpiece is revealed—at least to Poussin’s and Pourbus’s eyes—as “haphazardly accumulated colors contained by a multitude of peculiar lines, creating a wall of paint.” Either Frenhofer’s conception of art is so lofty that it is untranslatable into pigment; or, perhaps, what he has produced is so far ahead of its time that it can be appreciated only centuries later. In a rage (with himself, or the others?), he destroys all his paintings, and dies that night.

As a short story, it is somehow both rickety and overdense; as a narrative about the nature of art, it has a grasping intensity, which gave it the longest afterlife of any art fiction of the century. In his translation Anthony Rudolf enumerates the recognition from, and even influence over, Cézanne, Picasso, Giacometti, and de Kooning. (The story was also a great favorite of Karl Marx.) Picasso illustrated a livre d’artiste with choices that suggest, according to Rudolf, that he might not have read the text very carefully.

The link between writers and artists in nineteenth-century France was strong and largely cordial. But some writers went further—or imagined, or claimed, they did. Balzac described himself as “a literary painter.” Muhlstein calls Zola a “writer-painter.” Maupassant hymns the superiority of painting over fiction (though he was mainly talking about color). Proust is in Muhlstein’s eyes occasionally a kind of Cubist. Muhlstein charts the sudden irruption of the visual arts into the lives of nonelite Parisians: first, by the opening of the Louvre as a Central Museum of Arts in 1793; later, by the arrival of vast booty from Napoleon’s conquests (and the tenacious holding on to it after the empire fell). It was not just the thrilling, democratic availability of great art that excited writers; it was also that painters were “making it new” as much, if not more so, than writers. So writers now looked at how painters looked. Though Muhlstein’s claim that “the visual novel dates from this period” suggests too much. When was the novel—and before it, poetry—not “visual”?

You could say, perhaps, that writers look, whereas painters see. Muhlstein tells of Proust telling of Ruskin telling of Turner: how the English painter once did a drawing of some ships silhouetted against a bright sky and showed it to a naval officer. The sailor indignantly pointed out that the ships’ portholes were missing; the painter demonstrated that, given the light, they were in fact invisible; the officer replied that this might very well be the case, but he knew that the portholes were there. Writers look as hard as they can, but they may well falsely remember a porthole that is missing from the reality in front of them. Whereas painters have it both ways: they might Turnerishly omit the portholes, or choose to put them in, because they can also see what the rest of us can’t.

Advertisement

Perhaps the social closeness of French writers to painters in the nineteenth century made some of them think of themselves more self-consciously as writer-painters. Some of Muhlstein’s examples are very striking. So, Zola, in Une page d’amour (1877), gives five different descriptions of the same view of Paris, varying by time of day and season: the link to Monet’s (future) sequence-painting seems inescapable. (And he uses the same ploy in L’Oeuvre.) Then there is his picturish fascination with mirrors; and the way he justifies architectural anachronism in a Parisian cityscape because he needs the as-yet-unbuilt Opéra and the as-yet-unbuilt church of Saint-Augustin to give visual structure to his description.

But when, for instance, Muhlstein notes parallels in Zola between the representation of landscape and a character’s state of mind, this is not something new to literature: this is the Wordsworthian “egotistical sublime”—or, to take a more local example, the pantheistic trance of Emma Bovary after she has been seduced by Rodolphe in the forest. Contact with painters doubtless suggested new angles of looking and tweaks of lighting. But the book’s subtitle—“How Passion for Art Shaped Nineteenth-Century French Novels”—is overreaching. The fact remains that we don’t read Maupassant for the colors, or Zola for the lighting. We read Zola for the psychological truth, the social observation, and the tragic working-out of determinism. Further, the world of Zola—that “Homer of the sewers,” as the duchess so jauntily puts it in À la Recherche—is essentially one of darkness; the world of Impressionism essentially one of light.

While many of France’s nineteenth-century painters, from Delacroix to Monet to Cézanne, were very well read, and some of them drew inspiration from literature, not many of them—with the exception of Odilon Redon (“Writing is the greatest art”)—directly envied the form. As for what they made of their literary friends’ and supporters’ work, there is often more nuance and less full-heartedness in their response than you might expect. Indeed, some, like Van Gogh, writing in 1883, were very unnuanced: “Zola has this in common with Balzac, that he knows little about painting…. Balzac’s painters are enormously tedious, very boring.” Balzac and Delacroix, who met around 1829–1830, initially had much admiration for each another; Balzac dedicated La Fille aux yeux d’or to the painter, and over the years Delacroix copied into his journal twenty pages’ worth of quotes from Balzac, from thirteen different novels.

But a cooling-off happened around 1842, and thereafter Delacroix’s opinion of the novelist became harsher. By 1854, four years after Balzac’s death, the painter was fulminating into his journal against the panegyrical preface to Le Provincial à Paris, which boasted of Balzac’s “colossal reputation” and compared him to Molière. (Delacroix seems not to have known that “The Editor” was almost certainly Balzac himself.) And the next day, the painter went into detail: works like Eugénie Grandet hadn’t stood the test of time, he wrote, because of the “incurable imperfection” of Balzac’s talent. “No sense of balance, of structure, of proportion.”

You sense that Balzac was usually the wooer, Delacroix the wooed. Also that Balzac perhaps imagined Delacroix to be an artist other than he was. (When a flatterer congratulated him on being “the Victor Hugo of painting,” Delacroix chilled him with the response, “You are mistaken, Monsieur, I am a purely classical artist.”) It was Balzac, rather than the supposedly Romantic Delacroix, who was the more constant dreamer. He imagined giving his lover Mme Hańska Delacroix’s Les Femmes d’Alger—if only he could have afforded it. One of his saddest dreams took place in 1838 when, already on the run from creditors, he decided to build a country house called Les Jardies with a view over the woods of Versailles. His colossal initial plans were quickly scaled back to a “skinny three-storey chalet,” but within it, Balzac carried on dreaming, with everything from electric bells to a fireplace of Carrara marble. And the decor? That too Balzac had planned. As Robb explains in his richly observed biography:

The walls were bare except for Balzac’s charcoal graffiti, which became a permanent feature: “Here an Aubusson tapestry.” “Here some doors in the Trianon style.” “Here a ceiling painted by Eugène Delacroix.” “Here a mosaic parquet made of all the rare woods from the Islands.” There was also a charcoal Raphaël facing a charcoal Titian and a charcoal Rembrandt, none of which ever turned into the real thing: all signifiers and no signifieds.

Whether Delacroix knew he was down to do a ceiling for the novelist is doubtful.

As for Zola, his support for Manet and the Impressionists was much more public, and more publicity-conscious, and the painters were properly grateful. But their response to his L’Oeuvre (1885), the century’s most famous novel about art, was complicated. Its protagonist, Claude Lantier—the brother of Nana—has a succès de scandale at the Salon des Refusés, and founds a plein-air school, but ends up sacrificing fortune, wife, and child for his art. It was loosely assumed for some time that Lantier was based on Cézanne (though Lantier, like Zola, is a “naturalist”); further, that the book’s publication had caused a breach between the two old friends. This theory was based on the last-known letter from Cézanne to Zola, which reads in full:

Mon cher Émile, I’ve just received L’Oeuvre, which you were kind enough to send me. I thank the author of the Rougon-Macquart for this kind token of remembrance, and ask him to allow me to wish him well, thinking of years gone by. Ever yours, with the feeling of time passing, Paul Cezanne

As Alex Danchev wisely comments in his 2013 edition of the letters:

Cézanne’s words have been combed for any hint of telltale emotion—offence, anger, antagonism, rancour, shock, sorrow, bitterness, or merely coolness—as if the letter might contain the key to the rift. This exercise in runecraft has yielded remarkably little, except for wildly varying assessments of these few lines, and a tendency to read back into them the knowledge of what came later.

Indeed, it’s not even clear from the letter whether Cézanne had even started reading the novel when he acknowledged its arrival, let alone taken any offense. And as it turned out, this wasn’t the painter’s last letter to the writer: Muhlstein points out that a later one has very recently turned up. Even so, it wouldn’t be fanciful to scent some ambiguity or polite withholding in Cézanne’s words: the more so because such ambiguity was perfectly expressed by Monet, in his letter to Zola. Here is a fuller version than the one Muhlstein gives:

How kind of you to send me L’Oeuvre. Thank you very much. I always find it a great pleasure to read your books and this interested me all the more since it raises questions to do with art for which we have struggled for so many years. I have just finished reading it and I have to confess that it left me perplexed and somewhat anxious.

You took great care to avoid any resemblance between us and your characters; all the same I am very much afraid that our enemies in the Press and among the general public will bandy about the name of Manet, or at least our names, and equate them with failure, which I’m sure was not your intention. Forgive me for mentioning it. I don’t intend it as a criticism; I read L’Oeuvre with a great deal of pleasure, and every page recalled some fond memory. You must know, moreover, what a fan I am of yours and how much I admire you. My battle has been a long one, and my worry is that, just as we reach our goal, this book will be used by our enemies to deal us a final blow. Forgive me for rambling on, remember me to Madame Zola and thank you again.

This is fascinating, for many reasons: the gentleness of the reproach; the similar mention of the “fond memory” evoked by the book, rather than praise for its representation of art and artists; the assumption that the public will identify Lantier with Manet (rather than Cézanne); and perhaps, above all, the sense of vulnerability bordering on paranoia about the damage the novel might do to the cause of Impressionism, which had already been going strong for fifteen years. The fear that a “final blow” might be dealt to the movement—and worse, by a friend and ally, rather than a traditional enemy—is revelatory.

When Monet writes of “failure” being associated with the names of the Impressionists, he is also using it in a narrower sense. Lantier exemplifies what Muhlstein calls a “destructive perfectionism”—not unlike Balzac’s Frenhofer (though Zola furiously denied any Balzacian influence). Zola’s friend Paul Alexis, in advance of the writing of L’Oeuvre, noted that the novelist was “planning to explore the appalling psychology of artistic impotence.” Zola himself, writing about the “hysteria” of modern life, noted:

Artists are no longer big, powerful men, sane of mind and strong of limb, like the Veroneses and the Titians. The cerebral machine has gone off the rails. Nerves have gained the upper hand, and weak, wearied hands now try to create only the mind’s hallucinations.

Lantier, always a slasher of his own canvasses (like Manet, like Cézanne), is a creator with too much ambition, one who, as Zola put it, “fails to deliver his own genius,” and as a result goes mad and kills himself; not a single picture of his survives.

Pissarro didn’t think Zola’s book would do much harm to the Impressionists, even if it was “just not a great novel, that’s all”; but you can understand Monet’s “anxiety.” If this was how their great advocate presented his idea of the modern painter—as crazy, destructive, and self-destructive—what might Joseph Publique think? The truth was that most of the Impressionists worked hard and constantly, destroying only what they considered unworthy, and were far from crazy (the malleable myth of Van Gogh had yet to be constructed). The further truth remained that in describing artistic pathology, Zola’s actual model was neither Manet nor Cézanne, but himself. As he put it in his preparatory notes for the novel, “In a word, I will describe my own private experience of creativity, the constant agonizing labor pains; but I will expand the subject with tragedy.”

And then—jamais deux sans trois—along came Maupassant to compound the fiction writers’ well-intentioned sinning. Maupassant was also an excellent art critic, sympathetic to and appreciated by the Impressionists. In 1889, three years after L’Oeuvre, he published Fort comme la mort, his most underappreciated novel. Its central figure, Olivier Bertin, is a modern, fashionable society portraitist—a “conservative Impressionist” in Muhlstein’s words—who sounds more than a little like Jacques-Émile Blanche avant la lettre. He is taken into the household of the Comte de Guilleroy; he paints the comtesse’s portrait and, perhaps inevitably—this being a French novel—becomes her lover; the affair lasts ten years, and his portrait of her has pride of place in the house. What could be more suave, more fashionable, more Parisian? Except that the comtesse has a daughter, who grows up to resemble her mother (and therefore the portrait), and as the mother (unlike her portrait) ages, the painter finds himself becoming obsessed by the daughter.

Muhlstein mentions a recent theory that Maupassant’s source was a literary one: the rumor that Turgenev, for a long time in a contented ménage à trois with Pauline Viardot and her husband, had fallen disastrously in love with Mme Viardot’s daughter. Certainly, the novel had a literary consequence of some magnitude: Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier (1915). Looking back some years later, Ford wrote that “I had in those days an ambition that was to do for the English novel what in Fort comme la Mort Maupassant had done for the French.” He took from Maupassant the idea of violently transgressive passion; also the flaying difference between the easy love of youth and the desperate love of age. As Bertin puts it, trying to understand if not lessen his pain, “It’s the fault of our hearts for not growing old.” Faced with an impossible emotional—and social—dilemma, the painter throws himself beneath the wheels of a bus. And so another sympathetic novelist’s painter dies in torment: you might expect the Impressionists to get up a petition against such repeated libels.

Frenhofer, Lantier, Bertin… At least Proust’s Elstir doesn’t go mad and kill himself. Proust’s (and Swann’s) way of looking at pictures avoided addressing the work head-on, instead preferring to comment on which painted characters reminded them of which real people they knew in society. Indirection is all. There is a change of gear in this final section of Muhlstein’s book. Proust himself was more interested in classical than contemporary painting (though he approved of some Impressionists). Elstir—who is first introduced as a young prankster, then vanishes from the narrative for six hundred pages, emerging later as a “major artist”—is barely seen at work. Also, he is confected from many painters, and thus, as Muhlstein says, represents “the artist” rather than “an artist”—though he has many sly groundings in reality. Mme de Guermantes—while at the same time making a sign to the servants to give Marcel some more mousseline sauce for his asparagus—remembers that “Wait now, I do believe that Zola has actually written an essay on Elstir.” (And the asparagus is another hint: Elstir, just like Manet, painted a bunch of them.)

However, it is not one of Elstir’s pictures that everyone thinks of in connection with À la Recherche, but rather Vermeer’s View of Delft, “the most beautiful painting in the world,” according to Proust, with its famous little section of “yellow wall.” I confess that the first time I saw this painting I thought it not even the best Vermeer in the show, and then failed for a while to guess which bit of wall I was meant to be looking at. The most likely patch of pigment turned out to be a roof; but confusingly, although the roof was yellow, the thin sliver of actual vertical wall beneath it was more of an orange color (which all somehow confirmed what I had already suspected, that I shall never make a paid-up Proustian).

The dying writer, faced with the picture, comments, “This was how I should have written…. My last books are too spare, I should have applied several layers of color, made my sentences precious in themselves, like this little section of wall.” Would this have been a good idea? That question (since the writer is fictional) remains unanswerable. But Bergotte’s words act as a gentle underlining of what Muhlstein’s book often implies: that writers, of all artists, are the most anxious, and the most envious, about other forms of art.