1.

Just as Donald Trump was being inaugurated last January, the People’s Daily, the mouthpiece of the Chinese Communist Party, declared: “Western-style democracy used to be a recognized power in history to drive social development. But now it has reached its limits.” Two years earlier, China’s education minister, Yuan Guiren, told a conference of academics that they should “by no means allow teaching materials that disseminate Western values in our classrooms.”1 These statements are just two examples of an ever more evident theme of Xi Jinping’s tenure as China’s paramount leader. Behind the strident rhetoric lies a long-standing fear that somehow the “West” will take over and destroy China’s sense of itself.

The fear may be misplaced, but it is not surprising. The West and China have been intertwined for nearly two centuries, and the relationship has often been unhappy. What the Chinese call the “century of humiliation,” from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, lies at the heart of their political thinking about the wider world. The arrival of gunboats, missionaries, and the opium trade resulting in the Opium Wars of the mid-nineteenth century made Chinese observers believe that all Westerners had to offer was violence and commercialism.

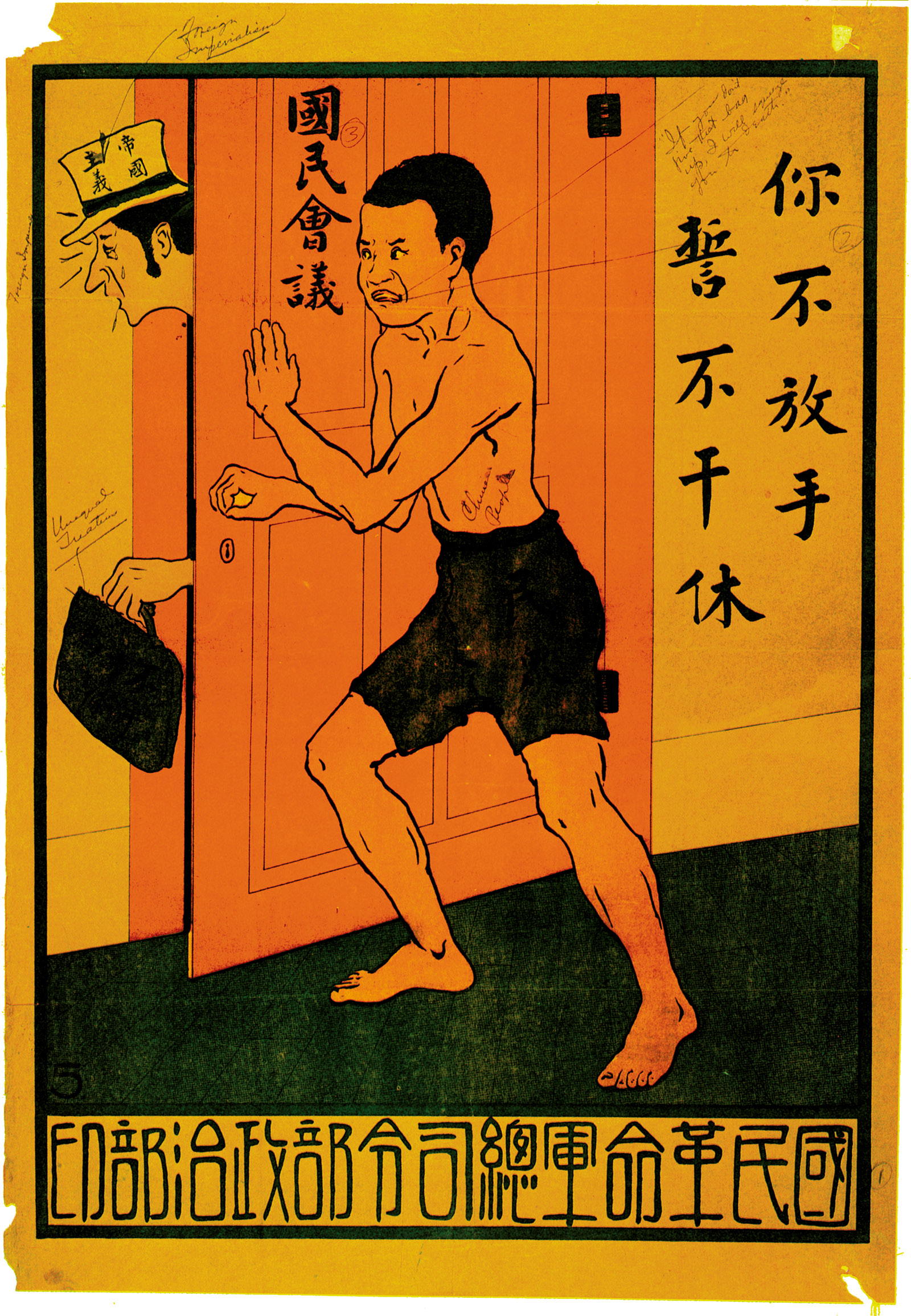

In the early twentieth century, the Chinese writers and intellectuals who championed a “New Culture” movement advocated adoption of Western political and cultural concepts such as Social Darwinism and anarchism while simultaneously rejecting the imperialist presence of Western nations. Today, too, the Chinese government officially speaks of the need for “internationalization”—through increasing its involvement with the UN and sending thousands of Chinese students overseas every year—while also warning its educators and students about the pernicious influence of the “West,” an ill-defined concept that apparently includes liberalism and constitutional reform but not Marxism or industrial capitalism.

During much of the period from the mid-nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century, China ceded territory and sovereignty to Britain, France, America, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, as well as its Asian neighbor Japan. In his new book, Out of China, Robert Bickers stresses the importance of this history for Westerners who wish to understand Chinese attitudes toward the wider world, although he remains skeptical of the idea—characteristic of much contemporary Chinese scholarship—that the period amounted to an “unrelenting Chinese nightmare.” His thoughtful, engaging, and well-written analysis helps to separate fact from myth when it comes to understanding the nature of Chinese nationalism.

2.

Out of China is a panoramic examination of the increasingly powerful articulation of China’s national identity in the twentieth century and the country’s painful encounter with Western imperialism. The book picks up from the end of Bickers’s last major work, The Scramble for China (2011), which detailed the rise of Western influence in China up to the 1911 revolution that overthrew the last emperor, Puyi. This account starts in 1918, at the end of the Great War, with a victory parade in the streets of Beijing led by the British community of Shanghai and the Chinese government at the time, which had committed China to the Allied side in 1917. (The 96,000 Chinese who went to Europe were not given combat duties but worked at the front, digging trenches and doing manual labor.) The rest of the book is divided into two sections: the first looks at China in the early twentieth century, weak but seeking to make itself strong; the second examines it later in the century, objectively strong but acting as if it were still weak.

Bickers begins by describing the growing sense of anger in China’s cities and rural areas over the influence of Western economic and political interests. The invasion of China in the mid-nineteenth century, first by the British but soon after by France, Russia, and Japan, among others, had deeply compromised the country’s sovereignty. China was never fully colonized, but portions of territory, such as Hong Kong and Dalian in Manchuria, were captured as spoils of the Opium Wars, the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, and the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905; and a system of treaty ports across China gave the West preferential trading rights. Perhaps most insidious was the system of “extraterritoriality,” which meant that Westerners were partially immune from Chinese commercial and criminal law anywhere within China, with foreign-dominated courts arbitrating disputes instead.

By the early twentieth century, Chinese anger against these arrangements had peaked. Centuries-old mistrust of foreign interference combined with a more modern nationalism based on the idea that China should be a free and sovereign republic, equal to others in the world. This was not just a Chinese phenomenon. In his influential study The Wilsonian Moment (2007), Erez Manela argued that Woodrow Wilson’s support for “self-determination” had inspired independence struggles across the colonized world, in places as far apart as India, Korea, and Egypt. Bickers shows that China’s delegates had come to the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 seeking nothing less than “the repudiation of Imperialism as a rule of action in the transactions of nations.”

Advertisement

Instead, China had to acquiesce to a dubious settlement in which former German colonial territory in China was handed over to Japan, which had entered the war in 1914 as one of the Allied powers. Chinese figures as different as the dapper diplomat V.K. Wellington Koo and the rural revolutionary Peng Pai all agreed after Versailles to focus on the same task: to strengthen China and remove the “unequal treaties” by which it had been controlled ever since the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing handed over Hong Kong to Britain. The Nationalist (Guomindang) government of Chiang Kai-shek won a precarious hold on power in 1927, compromised by fiscal weakness and the need to cut deals with the warlord leaders who controlled much of China away from the prosperous east coast. Yet it used its new authority to renegotiate sovereignty, slowly regaining autonomy over tariffs in 1930 and setting unilateral dates by which it expected the Western powers to end extraterritoriality.

This advance toward sovereignty was accelerated by the second Sino-Japanese war, which broke out in 1937 and lasted eight years. After Pearl Harbor, the war became global as the US and the British Empire formally allied themselves with China. The war had the ironic effect of making China weaker than it had been before, while also giving it symbolic strength in the global order. In 1937, China was still a semicolonized state. By 1945, it was one of the few fully sovereign states in Asia, with a permanent seat on the UN security council. But China’s improved international standing came even as its government was burdened by inflation, corruption, and human rights abuses, all of which contributed to the collapse of Chiang’s regime and his defeat by Mao Zedong’s Communists in 1949.

Mao’s China, by contrast, was freer to make its own choices in comparison to its predecessors, which had had to deal with a constant round of internal insurgencies and foreign invasions. Yet it was vulnerable in a different way. Pre-war China had been unable to keep foreigners out, even when it wanted to. Mao’s China, on the other hand, was prevented from allowing many of them in, as major Western powers (notably the United States) refused to open diplomatic relations. Mao was more inclined to focus on China’s relationship with the socialist bloc and to create new partnerships with the USSR and “fraternal” states such as Vietnam.

But by the 1960s, China had turned even further inward, and had begun to regard even old allies like the Soviets with suspicion. In the 1970s, after the opening to the US and the restoration of markets by Deng Xiaoping, China reversed course and made the journey toward political and economic strength that marks it today. But throughout that time, and even now, Beijing’s policymakers have remained fearful that China is only a step or two away from once more becoming a victim of a world that wants to alter the ideas and identity that it has developed internally over decades.

3.

One theme that distinguishes Out of China from much Chinese-language and Anglophone scholarship is its concentration on the part Britain played in shaping modern China. Broadly, the story of Sino-Western encounters in the twentieth century has been dominated by the tumultuous relationship between China and the US, with the principal participants on the American side being figures such as Henry Luce, a magazine magnate and Republican adviser, and Richard Nixon. Discussion of Europe’s influence on China during the twentieth century has been increasingly confined to shorthand secondary cultural references, such as the love of croissants that Deng Xiaoping developed in France as a student in the 1920s.

Yet Britain in particular profoundly influenced modern China. When architectural historians think of the great cities of British imperialism, Bombay and Cape Town tend to come to mind. They rarely mention Shanghai. However, a stroll down the Bund, the waterfront in the heart of the city, lined by buildings that combine imperial pomp with the art deco and modernism of the interwar years, reminds one of Britain’s historical dominance. Halfway down the Bund, the entrance hall of the old Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank (now the Pudong Development Bank) features mosaic murals of eight cities where it previously had branches, among them Calcutta, Hong Kong, and London. The bank was just one of the institutions that tied China to British imperial interests.

Technically, the center of Shanghai was an “International Settlement,” a term devised by the British in the nineteenth century to describe a zone that was run by an autonomous Municipal Council of foreigners, rather than by a colonial governor. Americans and Japanese contributed to the Settlement as councilors and taxpayers, supporting its police force and bureaucracy, but its government and culture were markedly British—at best, in Bickers’s phrase, a sort of “Anglo-cosmopolitanism.” More powerful, if less visible, was the Maritime Customs Service, established in 1854 to gather tariff revenue from imports. It was an agency of the Chinese government and lasted until 1950, but it, too, was shaped by Britain. All but one of its inspectors-general were British, and one of them, Sir Robert Hart, spent nearly half a century in charge.

Advertisement

Bickers analyzes the interaction between Britain and China, and divests it of any false romance or glamour. The sheer violence of colonialism echoes throughout the book. On May 30, 1925, police under British command, panicking as they were confronted by a demonstration against imperialism, shot at students and workers in central Shanghai; twelve died. Over the next few weeks, protests intensified across China. In Guangzhou (Canton) on June 23, a hot summer day, protesters gathered on Shamian Island. “We do not know who opened fire,” Bickers writes, “but we do know that in the ensuing twenty-minute slaughter, as French and British machine guns raked the column at 30 yards range across the canal, at least fifty-two Chinese and one Frenchman lost their lives.” This came just six years after the Amritsar Massacre in India, in which British troops opened fire on unarmed civilian protesters, perhaps the archetypal example of how empires ultimately rely upon violence to maintain control.

Bickers argues that the killings in China resulted in part from the imperial powers’ inability to understand that it had been moving, painfully but genuinely, toward becoming a modern society. Student nationalist movements, hygienic reform, and a strong Chinese presence at the League of Nations amounted to very little when the British were faced with a crowd of Chinese protesters. Indeed, “in most foreign eyes, every gathering was a potential mob” no better than the violent rebels who had besieged the foreign legations in Beijing as part of the Boxer Rebellion in the summer of 1900.

However, Britain began to lose its hold as China’s more outward-looking leaders realized that their anti-imperialist aspirations were better aligned with the American self-image than with that of the British or French. Many Americans felt that if the archetypal British figure in China was a red-coated soldier sacking the Summer Palace after the Boxers were defeated, then the American equivalent was a missionary or a sympathetic writer such as Pearl S. Buck. This image was only partially true at best, as the US shared in the spoils of imperialism; American missionaries and businessmen alike were protected by the hated system of extraterritoriality. Still, some Chinese persuaded themselves that the flattering image of the US as a champion of anti-imperialism put that nation firmly on China’s side.

Perhaps the most powerful Americophile was Song Meiling (Soong May-ling), often known as Madame Chiang Kai-shek, the wife of the leader of China’s Nationalist government from 1927 to 1975 (on the island of Taiwan after 1949). Song came from a wealthy Chinese diaspora family and was sent to Wellesley College to improve her knowledge of American customs and the English language. After war broke out between China and Japan in 1937, she lobbied ceaselessly in the US for American entry into the war in Asia (“China—first to fight!” read the posters intended to shame the neutral American public), and she knew the power of the unexpected gesture. “Two baby pandas arrived at the Bronx Zoo just after the Pacific War commenced,” Bickers notes drily, “heralded as ‘furry emblems of China’s gratitude’ for the work of United China Relief.”

Song Meiling has frequently been dismissed as a glamorous butterfly, and stories of her extravagance abounded during World War II. Bickers notes that in 1943, she supposedly reserved an entire floor of the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. Yet she was probably the single most prominent woman in global politics of the mid-twentieth century (rivaled only by Eleanor Roosevelt). Song and her husband, boosted by the Luce press, embodied the idea of China as a rising nation that deserved its own sovereignty. Chiang was the China insider, convinced that China needed authoritarian militarism to modernize and to expel the foreigners, a view that he expressed in his 1943 tract China’s Destiny. Song’s fluent, if florid, English and charming Westernized manners allowed her to convey to American leaders like Roosevelt and Wendell Willkie that Nationalist China was a nascent democracy not unlike the US. Liberal democracy was not, in the end, the destination of Chiang’s government. Still, the primary aim of Asia’s first power couple was achieved: when the war ended, no power, not Britain, the US, or Japan, would encroach on China’s rights. But it was their Communist successors who would reap the benefit.

4.

Even as China was trying to assert its independence from Western influence during the interwar years, its political and intellectual leaders began a new campaign to shape the way it was perceived by the West. In the 1930s, Japan was regarded as the most advanced and modern Asian power, and the increasing encroachment of Japanese troops into China was seen by at least some Westerners as no less than China deserved. To reassert its identity and resist Japan’s influence, the Nationalist government promoted China’s ancient culture. On November 28, 1935, the “International Exhibition of Chinese Art” opened at the Royal Academy of Art in London. Featuring a nineteen-foot-high, 1,300-year-old statue of the Maitreya Buddha, the exhibition of treasures from the Forbidden City served to demonstrate that China was not simply a supplier of curios but played a major part in a changing global story of art. Bickers argues that by making the case for China’s cultural longevity, the Nationalist government hoped to provoke sympathy for China’s political weakness.

In the US, the Chinese turned to the movie industry for their cultural promotion. Even in those early days, Hollywood’s producers sought to attract as many Chinese viewers as possible, and a thumbs-down from the censors in Nanjing (Chiang’s capital) could mean significant losses. Frank Capra’s The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1933), despite its relatively progressive attitude toward racial “miscegenation,” was roundly condemned by Chinese diplomats, and Columbia Pictures eventually issued an apology.

Astonishingly, the studios permitted a Chinese diplomat (the twenty-three-year-old Jiang Yisheng, who had never been to America before) to be stationed in Hollywood to approve plots as they were developed. When a film version of Pearl Buck’s best-selling The Good Earth was proposed, the Nationalists made it clear that “the film should present a truthful and pleasant picture of China and her people”; that “the Chinese government can appoint its representative to supervise the picture in its making”; and that “all shots taken by MGM staff in China must be passed by the Chinese censor for their export.” Similar preoccupations can be seen today. In the past decade, Hollywood blockbusters have frequently been edited to gain access to the highly lucrative Chinese market.2 But as far as we know, no diplomat from the Chinese consulate in Los Angeles has been placed on permanent censorship duty.

5.

Bickers takes us through the turmoil of Mao’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), years when a foreign presence in China was not only unusual but actively unwelcome. In the late 1970s, after Mao’s death, his successor Deng Xiaoping realized that China required knowledge of the outside world once again if it were going to strengthen its military and industrial capacity. What emerged and continues today was a China willing to embrace the outside world when it comes to trade and technology, while trying hard to keep foreign influence out of politics.

Bickers’s book ends with the transfer of Hong Kong from the UK to China in 1997. A song by the Chinese pop-folk singer Ai Jing, entitled “My 1997,” celebrated the event. The song (available on YouTube) has its own touches of nationalist anger. About pre-1997 Hong Kong, Ai sings: “He can come to Shenyang, but I can’t go to Hong Kong.” But it ends with an upbeat sense that Hong Kong’s return might open up new horizons for China’s youth.

That was twenty years ago. Recent events suggest that the future may involve closing borders for both China and Hong Kong. In August, three young Hong Kong activists from the Occupy Movement in 2014 were sent to prison for trespassing and disqualified from standing for Hong Kong’s legislature. In the same month, Cambridge University Press blocked articles about topics including Xi Jinping, Taiwan, and the Cultural Revolution in the electronic versions of its journal The China Quarterly in China (though the decision was quickly reversed after protests from scholars and human rights activists).

Nationalist voices in China appearing in such newspapers as the Global Times may sound hysterical. But a simple assertion of liberal values will not sound convincing to a Chinese elite and a public mindful of the history of imperialism that the “liberal” West visited upon their country within living memory. Out of China, underpinned by extensive research in archives and written in warm and often witty prose, seeks neither to condemn nor celebrate the Western presence in China. Instead, it is an important reminder that even when our shared history is forgotten in the West, it is very much remembered—and sometimes resented—in Beijing and Shanghai today.

This Issue

December 7, 2017

Norwegian Woods

Ku Klux Klambakes

Outing the Inside

-

1

Hannah Beech, “China Campaigns Against ‘Western Values,’ but Does Beijing Really Think They’re That Bad?,” Time, April 29, 2016 and “China Slams Western Democracy as Flawed,” Bloomberg News, January 22, 2017. ↩

-

2

Charlie Lyne, “The China-fication of Hollywood Blockbusters,” The Guardian, May 4, 2013. ↩