The past, in Poland, is not a foreign country; it is morality drama and passion play, combining high ideology and down-and-dirty politics. One recent manifestation of history’s significance has been the creation of several ambitious and architecturally inventive museums dedicated to central events and themes in the Polish past. Since the beginning of this century, four “houses of history” have opened in Warsaw and Gdańsk, attracting many visitors and contributing to the development of neglected neighborhoods. At the same time, the museums have inspired sharp controversies over such topics as freedom of cultural expression, the relationship of Polish to European identity, and interpretations of Polish-Jewish history.

At a time when Poland, with its unexpected hard-right turn and defiance of democratic principles, is once again a matter of European concern, these impressive institutions offer rich clues to the conflicts unsettling the Polish polity and the passions that historical disputes continue to arouse. Apart from undermining the independence of the judiciary and public media, the ruling Law and Justice party has now introduced a law making it a criminal offense to accuse the “Polish nation” of complicity in the Holocaust.

If recent debates about history have been turbulent, that is because they have followed a long period of ideological repression. In Poland, as in other formerly Soviet-dominated countries, the cold war decades were an era of censorship and deliberately falsified versions of historical events, including World War II and the Holocaust. Between 1939 and 1945, Poland was the epicenter of several violent upheavals: the Soviet invasion from the east under the auspices of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact; the Nazi conquest and occupation, which resulted in the deaths of three million non-Jewish Poles; and the attempt to exterminate the Jews of Europe, perpetrated largely on Polish soil, in which three million Polish Jews—90 percent of the country’s pre-war Jewish population—were murdered. In addition, Poland lost its eastern territories, now part of Ukraine, to the Soviet Union, and the region’s Polish residents were in effect deported westward. The enormity of these events, combined with the suppression of basic truths about them, meant that their legacies were preserved covertly by their various inheritors, all with their own adamant loyalties and wrenching recollections, and that Poland in the postwar period became a place of often conflicting and fervently defended forms of collective memory.

It was only with the lifting of censorship after 1989 that the past could be investigated, reexamined, and openly debated. The museums erected since then are projects of commemoration as well as documentation, bringing fully informed historical perspectives to highly charged memories and previously taboo subjects. The museums all run lively educational programs, and they have become newly important in the face of the current government’s attempts to control interpretations of history—this time from an arch-conservative rather than putatively arch-progressive standpoint.

These imposing and costly enterprises are the fruit of the post-1989 liberal interregnum, during which Poland underwent an economic recovery and joined the European Union. In addition to honoring the past, they can be seen as announcing Poland’s inclusion in that symbolic, as well as political, body: a declaration that Polish history should be as much a part of the European historical imagination as, say, French or German history has been for educated citizens of the advanced world.

No aspect of the Polish past has more pan-European relevance than that explored in the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. The idea for the museum began with a group of scholars from the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw after they visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. They proposed that the history of Polish Jews should be recognized in its own museum, and that this should cover not just the Holocaust but the entire thousand years of Jewish life in Poland.

They could not have chosen a history more fiercely contested or, for all its importance, less well known. In the postwar Jewish imagination, indeed in the imagination of the West, Poland had come to be associated almost exclusively with the Holocaust. It needs to be clearly said that the genocide was not the result of Polish policies. Poland had ceased to exist as a sovereign nation during the war, and Polish behavior during that most awful of times ranged from all too frequent episodes of informing or murderous violence to acts of extraordinary altruism in which Poles risked—and sometimes lost—their own lives in order to save Jewish people. But Poland was where most of the death camps were built and where the extermination of European Jewry largely took place; and for descendants of Polish Jews, as for many others, Poland came to be seen as the site both of the most profound trauma and of endemic anti-Semitism.

Advertisement

What had almost entirely vanished from collective memory was the fact that before World War II, Jewish and non-Jewish communities had coexisted in Poland for ten centuries, in a relationship that included phases of tension and benign indifference, of spiritual separateness and mutually advantageous commerce, of ideological anti-Semitism and what might be called multiculturalism avant la lettre. For several of those centuries, Poland had the largest Jewish population of any country in the world as well as proportionately the largest Jewish minority, with highly elaborate forms of communal life and institutions of learning central to Ashkenazi Jews everywhere.

The POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews opened in 2014, after a long period of fund-raising (through the first public-private partnership in post-socialist Poland) and of comprehensive discussions among historians from Poland, Israel, and North America It is housed in a strikingly simple building, covered with panels of glass, on which Hebrew and Latin letters etched in black mingle to subtly shimmering effect, and it stands in the heart of the former Warsaw Ghetto, facing the monument to the Warsaw Ghetto fighters, which was designed in 1948 by Nathan Rapoport. On the day of my recent visit, the steps of the monument were covered with bouquets of flowers. So was a memorial stone honoring Żegota, a Catholic resistance organization that established underground networks to save Jewish lives, including those of children, during the Holocaust. (A larger monument to Żegota is being planned.)

The brilliantly designed exhibition inside recounts the centuries-long history mostly through virtual, interactive displays that were considered highly innovative at the time the museum was conceived but that were also a solution to the dearth of actual objects from the vanished world of Polish Jews, especially from its earlier periods. The most stunning exception to the digital presentations is the painted vault of a wooden seventeenth-century synagogue from the town of Gwoździec, faithfully recreated from architectural drawings by the Handshouse Studio in Massachusetts, an organization devoted to the reconstruction of historical objects. The replica charmingly combines the folk style of wooden village houses with liturgical symbolism painted in cheerfully vivid colors. The synagogue was one of many that dotted the landscape of Polish shtetls, and an evocative example of the syncretism that arose naturally from the long coexistence between Poles and Jews.

Much of the procession through the ages is presented using murals depicting life-sized medieval figures and texts in various languages including, for example, the Catholic Church’s pronouncements of religious anti-Semitism and the surprisingly liberal Statute of Kalisz, which in 1264 accorded wide-ranging rights and protections to a new Jewish minority. There are interactive presentations of events such as the partitions of Poland at the end of the eighteenth century, biographies of early Jewish intellectuals, and paintings, photographs, and occasional film footage. Many visitors might be surprised to learn about the Council of Four Lands, a sort of federated body that governed the affairs of the Jewish minority in Poland between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries, or to follow, during the interwar period, both the rise of ethno-nationalist and sometimes violent anti-Semitism and the simultaneous flourishing of Jewish political parties and literary groups, which adopted one of the three languages available to them—Hebrew, Yiddish, or Polish—with accompanying discussions of “identity” that uncannily resemble our own.

The horror of the Holocaust is reconstructed in almost unbearable detail. Among the darkly familiar images, one finds poetry that was passed from hand to hand in the Warsaw Ghetto; despairing excerpts from diaries written in expectation of death; and a reconstruction of a bridge joining two parts of the Warsaw Ghetto, from which the viewer can see—as the Ghetto’s inmates did—images of ordinary life in the streets below. The museum then turns to the postwar period, during which emigration reduced the surviving Jewish population to today’s comparatively very small numbers, but Jewish life and cultural institutions have had an energetic albeit modest revival.

For all its attempts at completeness, the museum has drawn criticism, ranging from the charge that it doesn’t sufficiently honor the “righteous” Poles to accusations that it underplays anti-Semitism in various periods; from the contention that the exhibition underestimates the place of religion in Jewish life to suggesting, conversely, that it gives too much importance to piety. Perfect balance in presenting such a long and multidimensional history is difficult to attain, but the wide spectrum of objections may be an indirect tribute to the museum’s efforts to do so impartially. Whatever one’s reservations, it is hard to come away from the exhibition without understanding that Jews were a vital part of Polish life for centuries.

Advertisement

It may be that the museum, with its popular educational programs extending to provincial regions, has contributed to that awareness. Dariusz Stola, a historian of the twentieth century and the museum’s director, notes that despite the statistically discernible rise of anti-Semitism in Poland—along with the rise of xenophobic attitudes in general—interest in Jewish subjects has not subsided. The museum continues to draw record numbers of visitors, both from Poland and abroad, last year especially from Israel, where Poland has been to some extent rediscovered as the site not only of Jewish catastrophes but also of an important Jewish culture.

The Polish government’s recent introduction of the inflammatory “Holocaust bill” further confirms the need for the kind of complex understanding of history that the museum represents. Routine references to “Polish death camps” in other countries make Poles understandably defensive on behalf of their own, often ignored, history: the camps also imprisoned numerous non-Jewish Polish inmates. But the proposed law, which has elicited outraged protests, especially in Israel, is a rather transparent and dangerous attempt to stoke nationalist sentiment at a time when the Polish government, with its version of “illiberal democracy,” is waging a war against the liberal mandate of the European Union.

Dariusz Stola has made an eloquent statement on behalf of the museum, pointing to the Third Republic’s proud record of open debate on difficult issues including the fraught question of Polish participation in the Holocaust and its most painful episodes—such as the massacre of Jewish inhabitants of the town of Jedwabne by their Polish neighbors. He emphasized the need for disseminating knowledge about a complex past rather than stifling discussion through judicial measures. It is to be hoped that his voice, among many others, will help to get the legislation withdrawn or at least meaningfully modified.

The Warsaw Rising Museum addresses an event that outside of Poland is still often confused with the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. In postwar Poland, memories of the uprising contributed to a pervasive sense of grievous historical injustice and to the stubborn opposition to Communist regimes. The uprising was launched in 1944 by the Polish underground resistance movement—the largest in Europe, and working against nearly impossible odds—in the hope of liberating the capital from the German occupation and thus also averting a Soviet takeover. Instead, the insurgents were defeated after sixty-three days of fighting, during which more than 154,000 people, most of them civilians, lost their lives and Warsaw, fulfilling Hitler’s longstanding plan, was reduced to rubble by the retreating German army. The Soviet army, following Stalin’s cynical orders, stayed on the other side of the Vistula River and waited for the city to be destroyed before moving in, then went on to wreak its own mayhem as it moved west toward Germany. Since then, the question bitterly debated has been whether the uprising was an act of courage necessary to save the nation’s self-respect, with a real possibility of winning its freedom, or an example of Polish heroics in which lives were needlessly—and heedlessly—sacrificed.

The museum dedicated to this event opened in 2004, and it uses every means at its disposal to convey not only information about the uprising and the subtleties of the arguments surrounding it, but its devastating drama. The main part of the museum is situated in a building that served as a powerplant for Warsaw’s tramway system in the early twentieth century; its industrial architecture is well suited to the somber exhibition. When I visited, the crowds waiting to get in consisted, as they apparently often do, largely of young people. Inside the irregularly shaped and darkened interiors, disturbing, low-register music accompanies a variety of exhibits, including video cabinets with antique telephones on which you can hear reminiscences of participants in the uprising, some of whom were adolescents when they volunteered, and their poignant exchanges with their parents, who were often anguished about their children’s decision to fight but rarely tried to stop them. Elsewhere one finds biographies of insurgents who were imprisoned and sometimes sentenced to death by the Communist authorities after the war, a piece of rank malfeasance that fed the fierceness of anti-Communist memory for decades.

The exhibition reflects the significant contributions of women who participated in the uprising by making food for the increasingly starved population, tending to the wounded in hospitals, or working in the newly free underground printing presses, one of which has been reconstructed. On display are insurgents’ uniforms and military objects, ranging from a German motorcycle and rocket to less powerful Polish weaponry. A structure of tight round tunnels is intended to recreate the experience of moving through sewers, as people often had to during the uprising (a subject depicted in Andrzej Wajda’s great film Kanał). A theater shows some of the film footage made daily during the uprising and featured each evening in a Warsaw cinema, with commentary provided by the director. There are moving pleas from scholars to Warsaw’s population to preserve the cultural heritage of the capital; but also a recording of a Soviet radio broadcast encouraging Poles before the uprising to resist the Nazis, and one of Stalin saying, after the event, “I’m sorry for your people’s losses—but the uprising came too early.”

It’s the question of Soviet perfidy that comes up when I ask a young man about an exhibit of an RAF Halifax airplane, which had been shot down as it tried to deliver aid to the insurgents. He explains to me that the Soviets prevented Allied planes from using Soviet airfields, leading to the deaths of many pilots. His well-informed answer is given in a tone of almost trembling emotion, difficult to imagine among adolescent visitors to, say, the Imperial War Museum in London.

Jan Ołdakowski, the museum’s director, said that the history of the uprising speaks to the sensibilities of young people, who are drawn to their grandparents’ ideals of patriotism and resistance. Indeed, some of the museum’s critics have charged that it is too patriotic by half—and even that it propounds a Polish victory. Given that the exhibition’s final images are of Warsaw in ruins, this criticism suggests less a response to the museum’s presentation of events than liberal critics’ desire to distance themselves from anything resembling militant nationalism. For Ołdakowski, the museum shows both the terrible costs of the uprising and the legitimate desire of its participants to win their own freedom at a time when the nation was caught between two totalitarianisms.

Perhaps the difficulty of interpreting the museum’s message reflects the difficulty of judging the uprising itself. The museum’s advisory board included historians critical of the uprising, as well as some who admire it. Yet others have suggested that this calamitous episode had the classic outlines of a tragedy—there were no good choices to be made. When I brought this up in conversation with Adam Michnik, the leading Solidarity dissident and a powerful moral voice in post-1989 Poland, he responded with one word: “Shakespeare.” Poland’s wartime history in all its phases demands an exceptional tolerance for ambiguity and an acceptance of moral complexity.

Divergent ideas about what constitutes patriotism in contemporary Poland have likewise been at stake in the closely watched struggle between the recently opened Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk and the leaders of the Law and Justice party. Paweł Machcewicz, a historian who would become the museum’s founding director, first suggested that it was needed in a 2007 newspaper article. He was responding in part to a movement within Germany to create a museum commemorating the expulsions of Germans from Poland and elsewhere at the end of World War II. The emphasis on German victimhood (with accompanying demands for reparations) struck almost all Poles as a hurtful distortion of historical truth, ignoring questions of causality and responsibility.

Machcewicz thought that a fitting response would be to create a Polish museum that would place the expulsions of Germans and others in their proper perspective and show the effects of the war on populations around the world. His idea was taken up swiftly by Donald Tusk, the new prime minister, who mentioned it during his first conversation with Angela Merkel in the hope of persuading her that such a museum would make a German commemoration of “expellees” unnecessary. She was not persuaded, but Tusk approved the project of the museum, with funds to come from Polish sources. It was originally to be located in Westerplatte, a peninsula in the Gdańsk harbor, but soon moved to a location closer to the center of the city and to the post office where one of the first attacks of the war took place on September 1, 1939. After defending the building for fifteen hours, the staff (aside from four who escaped) was executed—presaging the mass killings of Polish civilians, beginning with the country’s elites.

The museum itself, topped by a red-framed, leaning glass tower, is almost sculptural in effect, with the huge exhibition located deep underground. The intention of the museum’s founders was clear from the outset: to show the war in its global dimensions and to emphasize the suffering of civilians, who, in contrast to previous conflicts, numerically bore the war’s greatest losses. But it was also, Machcewicz has written, “to insert the experiences of Poland and east-central Europe into Europe’s and the world’s historical memory.”

The exhibition was scheduled to open in 2017. But in August 2015, the new conservative government was elected, and a reliably informed colleague told Machcewicz that he was a “dead man.” In the eyes of the new authorities, the museum was insufficiently patriotic or inspiring; the inclusion of other nations and the universalization of suffering in its account portended a dangerous dilution, or “Europeanization,” of specifically Polish history and identity. Machcewicz insisted that the museum would do just the opposite. He says that he knew from his travels abroad that the Polish part of the war remained virtually unknown outside the country, and that placing it in a larger setting would make its exceptional circumstances—and the exceptionality of the Polish resistance—more evident.

It is hard to disagree with him as one walks through the exhibition and contemplates the global progress of the conflict and its appalling cruelties. Parts of this story are better known than those told by Poland’s other recent museums, but the presentation in the Gdańsk museum, which includes hundreds of poignant individual details and shows the sheer scale of collective suffering, both deepens and enlarges one’s understanding of what is meant by “total war.”

Preventing the museum from opening became one of the main planks of the new government’s “cultural policy.” Its tactics, which Machcewicz details in his book Muzeum (2017), were astonishing: late-night visits to his apartment by functionaries of the Central Anticorruption Bureau to disturb his family in his absence; attempts to move the museum to Westerplatte, thus nullifying the existing institution; and investigations of Machcewicz and his colleagues on fabricated charges of financial irresponsibility.

Machcewicz fought back fearlessly, and although there were attempts to remove him from his position, he managed to shepherd the museum through to its opening on March 23, 2017. On April 6, the museum was officially liquidated through a legal ploy and then reestablished immediately, with a new director who belongs to the ruling party and has no background as a historian. But despite the government’s earlier threats to remove many artifacts, the contents of the museum have so far remained almost untouched.

The one major change under the new dispensation has been to replace a film at the end of the exhibition, which showed stark contrasts between the postwar East and West and the persistence of wars until today, with one that catalogs acts of Polish heroism in a rather portentous tone. Since then, Machcewicz and three of his colleagues have brought a case against the museum’s new director in the provincial court in Gdańsk, claiming their authorial rights to the exhibition and demanding its restoration to its original form. Machcewicz and his colleagues continue to be subjected to court hearings and other forms of harassment. Nevertheless, the opening of the museum in a mostly unchanged form surely constitutes a victory, however bittersweet, for its founders and their strategy of open political resistance.

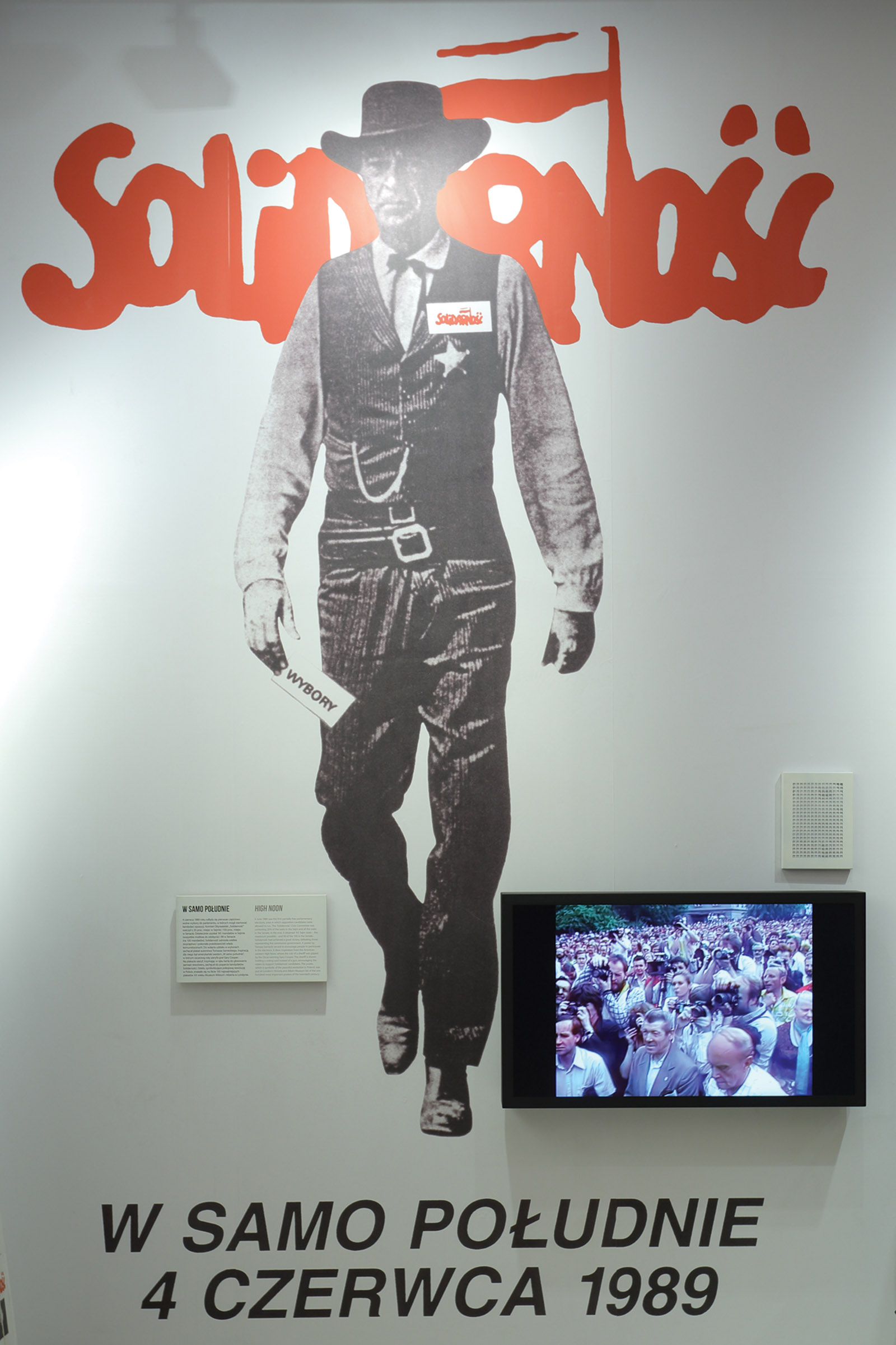

The theme of nonviolent resistance is at the heart of Gdańsk’s other new museum: the European Solidarity Center, which opened in 2014. This sturdy, beautiful building, fronted by a glass-and-metal façade, with a lovely garden overlooking the Gdańsk shipyard, is both a museum to commemorate one of the world’s few nonviolent revolutions and a cultural hub that sponsors discussions and events with participants from all of Europe.

For those who remember following Solidarity’s dramatic progress on the news, some of the images in this comprehensive museum—of the young Lech Wałęsa being hoisted aloft by cheering shipyard workers or the roundtable negotiations that ushered in a bloodless transition to democracy—are nostalgically thrilling. “I am very glad,” the museum’s director Basil Kerski stated,

that against the background of heated political conflicts in Poland, ECS is a place of calm, civilized debates, respect for the other. I will frankly admit that, as I observed the rising temperature of political discourse…I was worried that the atmosphere of division will also cross our threshold. I am very happy that this did not happen.

He thinks that there is much to learn today from Solidarity’s inclusive pluralism, which embraced all parts of society, and its capacity to compromise when doing so was necessary to avoid violent conflict. He also points out that by breaking the USSR’s domination over Eastern Europe, Solidarity changed the configuration of the continent—however difficult and divisive the conditions of freedom have turned out to be.

As for the future of Poland’s cultural institutions, Kerski says that much depends on what might be called the civic courage of individuals in opposing repressive policies, as well as on the credibility of the European Union. The courage has not been lacking; but the Solidarity Center stands as a reminder that democratic freedom, once so ardently fought for, needs once again to be defended. The other museums also serve as testimony to the history of a country that has at many critical junctures been crucial to Europe’s fate, and that may yet become one of the testing grounds on which the very idea of Europe succeeds or fails.

This Issue

March 22, 2018

‘I Should Have Made Him for a Dentist’

Fine Specimens