Americans in the second half of the nineteenth century had no sure prospect of resting in peace after death. If their bodies weren’t embalmed for public viewing or dug up for medical dissection, their bones were liable to be displayed in a museum. In some cases, their skin was used as book covers by bibliophiles and surgeons with a taste for human-hide binding.

The preservation, exhumation, and exhibition of human remains become, in the hands of the literary critic Lindsay Tuggle, an illuminating basis for a provocative reassessment of America’s foremost poet, Walt Whitman. In The Afterlives of Specimens, Tuggle aligns Whitman’s life and work with the practice of preserving and learning from cadavers or body parts during the Civil War era. She offers new insights into Whitman’s poetics of the body, both by limning the history of body preservation and by considering his development using the work of various psychologists and literary theorists, including Sigmund Freud, Jacques Derrida, and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick.

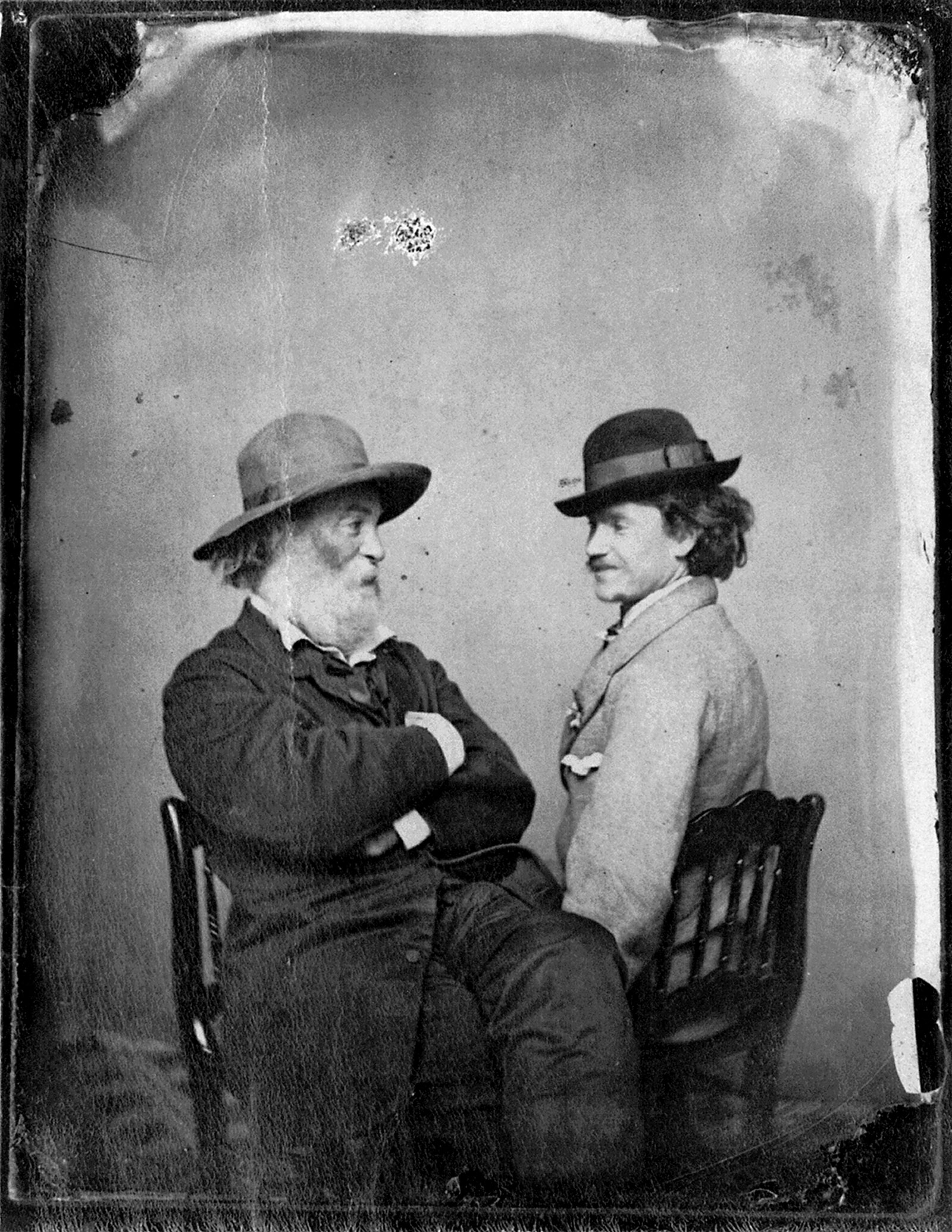

Whitman, long recognized for his candid treatment of the body and sexuality, was also the quintessential poet of disability and death. As a volunteer nurse in the Civil War hospitals in Washington, D.C., he visited, according to his own estimate, between 80,000 and 100,000 wounded or sick soldiers over the course of four years. He typically went twice a day to the hospitals, walking from cot to cot, tending to the soldiers, giving them food or small gifts, reading to them, writing letters for them, or sitting quietly by their side. Although his daily visits took a toll on him (he developed tuberculosis during the war), he got pleasure—including, it appears, homoerotic arousal—from his encounters with soldiers who stoically faced death or permanent disability.

Whitman was also inspired by the war to write new poetry. In the early spring of 1865, he arranged to publish a collection, Drum-Taps, that was delayed due to Lincoln’s assassination in April and appeared along with a sequel later that year. This volume contains the finest Civil War poetry we have. Its republication as Drum-Taps: The Complete 1865 Edition, expertly introduced and annotated by Lawrence Kramer, is most welcome. Since Whitman dispersed his war poems, often heavily edited, throughout later editions of his magnum opus Leaves of Grass, these poems have previously been available to general readers only in truncated, scattered form. Kramer’s edition of the original 1865 Drum-Taps and its sequel restores Whitman’s immediate creative response to the war that killed more than 750,000 Americans and injured at least 500,000 others—more American casualties than in all other wars combined.

Some poems in Drum-Taps look unblinkingly at the horror of war. In one, Whitman describes his work as a hospital nurse:

From the stump of the arm, the amputated hand,

I undo the clotted lint, remove the slough, wash off the matter and blood,

Back on his pillow the soldier bends, with curv’d neck, and side-falling head;

His eyes are closed, his face is pale, he dares not look on the bloody stump,

And has not yet looked on it.

The poem’s speaker next tends to “a wound in the side, deep, deep,” and then to one that festers “with a gnawing and putrid gangrene, so sickening, so offensive.”

In another poem, Whitman describes a battlefield strewn with corpses; the moon shines down “on faces ghastly, swollen, purple;/On the dead, on their backs, with their arms toss’d wide.” In the poignant “Vigil strange I kept on the field one night,” a soldier sits all night by the body of a fallen comrade, then wraps it in a blanket and buries it.

The sheer physicality of death and disability in the Civil War, accentuated in graphic battlefield photographs taken by Matthew Brady and others, leads Tuggle to identify a pattern in Whitman’s literary career, which she follows across the six editions of Leaves of Grass and the late prose works, with the war writings as her main focus—an apt choice, since according to the poet, “my book and the war are one.” Tuggle shows that before the war Whitman emphasized the chemical transformation of the interred body into new life. He writes in the first edition of Leaves of Grass (1855): “And as to you corpse I think you are good manure, but that does not offend me,/I smell the white roses sweetscented and growing.” Tuggle links this notion of organic regeneration with Whitman’s prewar criticism of body-snatching—the exhumation of corpses, primarily for dissection by physicians—which occurred frequently in this period.

The sudden surfeit of cadavers during the Civil War, Tuggle contends, corresponded to a notable change in Whitman’s approach to the human body. Instead of compost for new growth, the body became a specimen for public exhibition and scientific analysis. Tuggle notes how important the term “specimen” became for Whitman, who wrote of “thousands of specimens of first-rate Heroism” among soldiers he visited. He described “a specimen army hospital case…Lorenzo Strong, Co. A, 9th United States Cavalry,” with his right leg amputated, “the perfect specimen of physique—one of the most magnificent I ever saw”; a New Hampshire soldier with “gangrene of the feet, a pretty bad case: a regular specimen of an old-fashion’d, rude, hearty New England country man”; and a New Yorker, “a regular Irish boy, a fine specimen of youthful physical manliness—shot through the lungs—inevitably dying.”

Advertisement

At the same time, Tuggle informs us, medical science analyzed human specimens: corpses, body parts, and bones. Especially striking is her account of the Army Medical Museum in Washington, D.C., begun in 1862 and curated by the surgeon John H. Brinton, who collected the bones of soldiers killed in the Civil War and put them on display, with identifying labels. One of Whitman’s first sights when he arrived in Washington that year was “a heap of amputated feet, arms, legs, hands, & c., a full load for a one-horse cart” sitting outside a war hospital. These were the kinds of specimens that Brinton gathered, cleaned, and displayed. He presented the bones as evidence of the effect of new weaponry, such as the powerful bullet known as the minié ball, and as mementoes of the war and its martyrs.

It was considered a noble gesture, Tuggle reveals, for a soldier to contribute the remains of a dead comrade to Brinton “for the good of the country.” The bones of four soldiers Whitman had visited in the hospital were on display in the museum, which fed the curiosity of sensation-seekers even as it created a memorial of the war. One journalist called it “a museum of horrors” but recognized its appeal: “Its many bones, which never ached, and which have survived their painful sheaths of mortal flesh, all cool and clean, and rehung on golden threads, are not unpleasant to behold.”

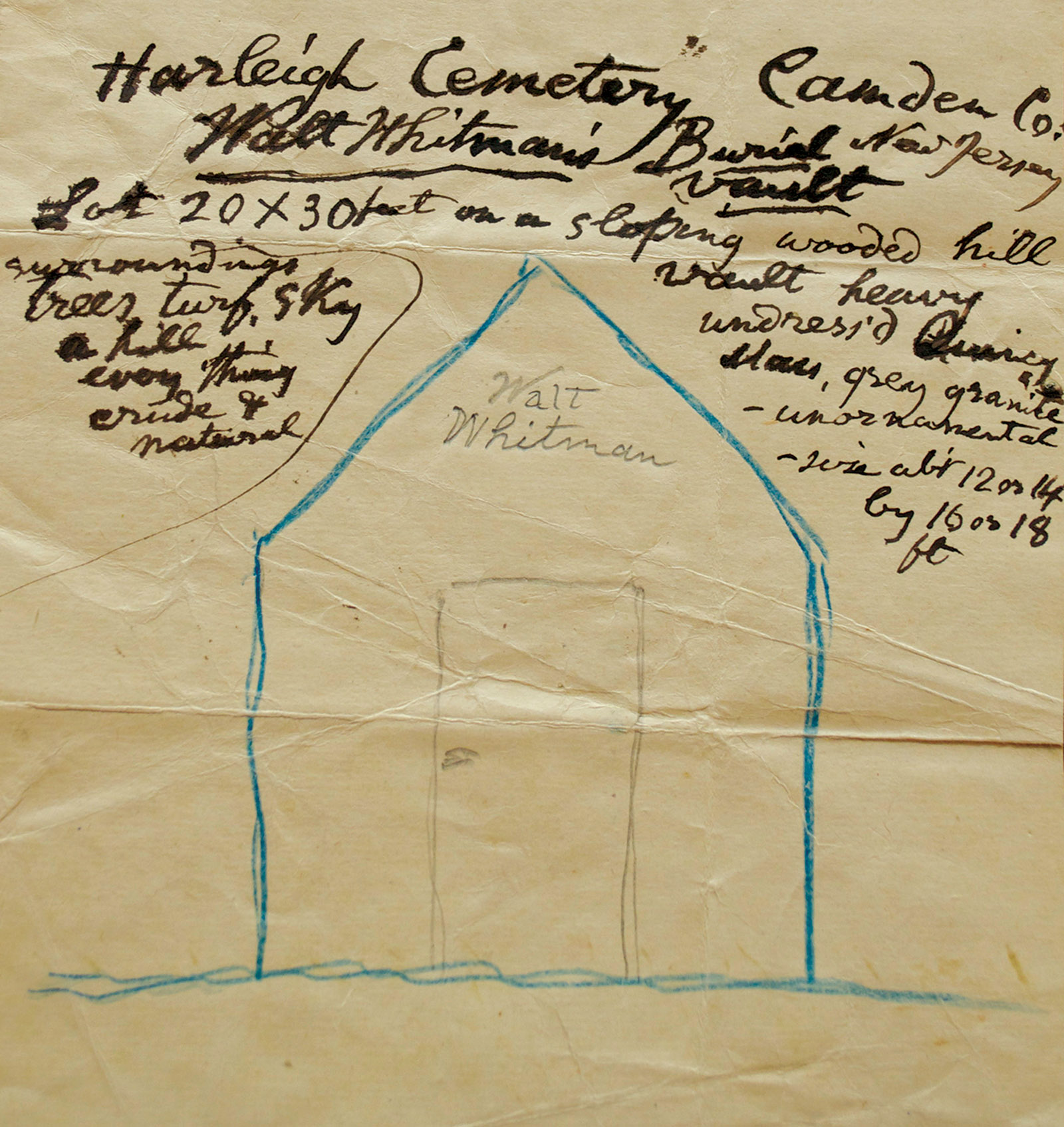

Human remains became such an overwhelming presence during the war that Whitman suggests that the earth is incapable of absorbing them. In both his poetry and his prose, Tuggle writes, “Whitman shifted from a focus on cyclical regeneration (‘composting’) toward a poetics of preservation (‘embalming’).” She points out that Civil War doctors perfected the art of embalming, as in the case of the assassinated Lincoln, whose corpse was drained of blood and injected with fluid that rendered it “hardened to the consistency of stone,” as a reporter put it. In this condition Lincoln’s body made its twelve-day, 1,700-mile train journey from the nation’s capital to Springfield, Illinois, viewed by millions of Americans when it stopped in many cities along the way.

Whitman’s war writings, according to Tuggle, performed a similar service of embalming both the president and myriads of fallen soldiers as specimens that remained in the poet’s sad memory. “Embalming” not only describes his literary preservation of the war in the retrospective poems and prose he wrote during the postbellum decades, but it also appears as a metaphor. For instance, in the 1890 poem “A Twilight Song,” written toward the end of his life, Whitman says of the war dead: “Your mystic roll entire of unknown names, or North or South,/Embalm’d with love in this twilight song.”

Tuggle thoughtfully analyzes Whitman’s experience of mourning, in which melancholia, nostalgia, and the poet’s physical decline (he was forty-one when the war began) were intertwined. With regard to Whitman’s “specimen soldiers,” she writes that “as symbols of embodied mourning, Whitman’s specimens conjure psychic and physical attachments that were, melancholically, impossible to sever.”

This approach illuminates a number of the original war poems as they appear in Kramer’s edition of Drum-Taps. The most moving poems in the volume, after all, are the portraits of the maimed or the dead; verses about the shattering effect of battlefield losses on family members; vignettes of soldiers in battle or on the march or bivouacked on a hillside. These poems are more than realistic or photographic—adjectives normally used to describe them. They are emphatically physical, alive with the sights, sounds, and smells of war. The vividness of poems like “The Veteran’s vision” (about the “grime, heat, rush” of battle), “A sight in camp in the day-break grey and dim” (describing three soldiers’ corpses), or “A march in the ranks hard-prest, and the road unknown” (picturing a field hospital filled with a “crowd of the bloody forms of soldiers”) substantiates Tuggle’s point about Whitman’s painful, “embodied” memories. Also, her interweaving of psychoanalysis and queer theory illuminates certain poems, such as one that ends: “(Many a soldier’s loving arms about this neck have cross’d and rested,/Many a soldier’s kiss dwells on these bearded lips.)”

Advertisement

But Tuggle underplays the complexity of Whitman’s response to the Civil War. The poems in Drum-Taps show clearly that he used poetry not only to memorialize specimens of the war but also to hail the war as a social cleansing agent and as a powerful force for union in America. Mourning was just one of several of Whitman’s responses to the war, which he viewed far more positively than she allows.

Before the war, Whitman had been appalled by corruption in the US government, which he said swarmed with “cringers, suckers, doughfaces, lice of politics,” including Franklin Pierce, about whom he wrote, “The President eats dirt and excrement for his daily meals, likes it, and tries to force it on The States.” Whitman continues, “The cushions of the Presidency are nothing but filth and blood. The pavements of Congress are also bloody.” Whitman characterized Pierce and two other presidents, Millard Fillmore and James Buchanan, as America’s “topmost warning and shame,” saying they showed “that the villainy and shallowness of rulers…are just as eligible to these States as to any foreign despotism, kingdom, or empire—there is not a bit of difference.”

He was convinced that the war purified the national atmosphere like a thunderstorm. In Drum-Taps he greets it as the savior of an America that had gone terribly awry. “I waited the bursting forth of the pent fire,” he writes, “I waited long;/—But now I no longer wait—I am fully satisfied—…/I have lived to behold man burst forth, and warlike America rise.” Drum-Taps at times becomes stridently militaristic:

War! an arm’d race is advancing!—the welcome for battle—no turning away;

War! Be it weeks, months, or years—an arm’d race is advancing to welcome it.

Initially, in Whitman’s view, the war spirit burst through the venality and materialism that he thought had nearly ruined America in the 1850s. Believing that Southern soldiers exhibited just as much heroism and self-sacrifice as Northern ones, he asks in one Drum-Taps poem, “Was one side so brave? the other was equally brave.” In another, he insists that the war bolsters “the CONTINENT—devoting the whole identity, without reserving an atom,” because the war is “for all!/From sea to sea, north and south, east and west,/Fusing and holding, claiming, devouring the whole.”

His poems about the later stages of the war become darker, but his hope for national union was revived after Lincoln’s death. In his poems about the murdered president, he shifts between the emotional fervor of “O Captain! my Captain!” and the nature-bathed lyricism of “When Lilacs last in the door-yard bloom’d.” Like much of the nation, Whitman had become war-weary, but since Lincoln’s passing was mourned throughout the North and even in much of the South, Lincoln stood, above all, Whitman wrote, for “UNIONISM, in its truest and amplest sense”; his memory “belong[ed] to these States in their entirety,” thus providing “a cement to the whole people, subtler, more underlying, than any thing in written constitution, or courts or armies.”

Union was an admirable goal, but Whitman never fully learned a main lesson of the Civil War: it was, most urgently, a war over slavery. Kramer in his introduction to Drum-Taps insightfully discusses the poet’s ambivalent position on slavery. On the one hand, he opposed it and spoke out against its westward spread. He also sometimes portrayed African-Americans sympathetically in his poetry. On the other hand, he denounced radical abolitionism, which called for the separation of the North and the South unless the nation’s four million enslaved persons were immediately emancipated.

Like many other prominent white Americans, from Benjamin Rush through Harriet Beecher Stowe and Theodore Parker, Whitman stood against slavery but was capable of making racist pronouncements. Lincoln, too, could sound racist early on, but he progressed on race, whereas Whitman did not. While Lincoln in his final public speech floated the idea of African-American citizenship, Whitman opposed suffrage for blacks in the years just after the war. He also bought into ethnographic pseudoscience, which predicted the disappearance over time of “inferior” races. Antislavery sentiment is notably absent from Drum-Taps, which makes overtures to the South in the interest of reconciliation and national unity. In the poem “Pioneers! O Pioneers!” he embraces slave-owners:

All the hands of comrades clasping, all the Southern, all the Northern,

Pioneers! O pioneers!…

All the seamen and the landsmen, all the masters with their slaves,

Pioneers! O pioneers!

Drum-Taps, then, has as much to do with Whitman’s politics as it does with the preservation of human specimens of the war. The poems in the volume also lead us to question Tuggle’s argument that his focus on composting and regeneration was replaced by the preservationist theme of embalming. Actually, Whitman’s 1855 motif of the corpse as compost reappears in Drum-Taps, as when the poet describes Mother Nature calling on the earth to absorb fallen soldiers’ bodies: “Absorb them well, O my earth, she cried—I charge you, lose not my sons! lose not an atom.” The speaker invokes the soil, the streams, the rivers, and the roots of trees to transform soldiers’ corpses into future vegetation and air: “Exhale me them centuries hence—breathe me their breath—let not an atom be lost;…/Exhale them perennial, sweet death, years, centuries hence.”

Not only does Whitman in Drum-Taps retain his belief in the organic recycling of bodies; he also pays homage to the soul. On the body/soul issue Tuggle does a deft dance. She discusses Whitman in relation to spiritualism—contact with departed spirits—and animal magnetism, with its belief in an electrical fluid known as the odic force. Into the mix she casts the phenomenon of phantom limbs, discovered by the Philadelphia physician and author Silas Weir Mitchell. Mitchell found that war amputees frequently had an uncanny sense of their missing limbs—a psychosomatic condition that Tuggle links to Whitman, for whom deceased soldiers were ever-present figures. “Like Mitchell’s ‘spirit members,’” she writes, “Whitman’s description of soldiers as ‘spiritual characters’ situates his specimens as performers in a fashionably macabre contemporary discourse.” This point casts a fresh light on certain lines in Drum-Taps about the war dead, such as these:

Phantoms, welcome, divine and tender!

Invisible to the rest, henceforth become my companions;

Follow me ever! desert me not, while I live.

The “afterlives of specimens” in Tuggle’s title, then, refer to the continuing presence of bodies or body parts, either as phantom limbs, preserved corpses, museum exhibits, or traumatic sights of war that haunted Whitman. At times, Tuggle suggests that Whitman conflates the spiritual with the physical. She writes, “Like [the amputee] Lewy Brown’s lost toes, for Whitman the body and the soul are ‘impossible to disentangle.’”

We should keep in mind, however, that the metaphysical realm was very much a reality for Whitman. Although he rejected conventional religious explanations of the afterlife, he believed in the immortality of the soul. This was his main dispute with “the Great Agnostic” Robert Ingersoll, who loved his poetry but, unlike Whitman, believed that there was nothingness after death. In a public discussion, Whitman asked Ingersoll, “What would this life be without immortality?… If the spiritual is not behind the material, to what purpose is the material?” He addressed these questions privately by telling his companion Horace Traubel, “I am not prepared to admit fraud in the scheme of the universe—yet without immortality all would be sham and sport of the most tragic nature.”

Among the poems in Drum-Taps is “Chanting the Square Deific,” about religion. The poem describes four conceptions of God: as an angry judge, like the Old Testament’s Jehovah; as a loving consoler, such as Christ; as Satan, the fallen God; and as what Whitman calls “Santa SPIRITA,” the “essence of forms—life of the real identities, permanent, positive…the most solid” of realities. Santa Spirita, the deathless essence within all humans, is what Whitman champions. In a later poem about religion, “Eidólons,” the poet reaffirms his faith, insisting upon a spiritual reality behind everything. He describes the eidólon as “Thy body permanent,/The body lurking there within thy body,/The only purport of the form thou art, the real I myself,/An image, an eidólon.” In 1891, the year before he died, Whitman published the poem “Sail Out for Good, Eidólon Yacht!,” which contains the lines:

Depart, depart from solid earth—no more returning to these shores,

Now on for aye our infinite free venture wending,

Spurning all yet tried ports, seas, hawsers, densities, gravitation,

Sail out for good, eidólon yacht of me!

In Whitman’s cosmic view, then, the decomposed body nurtures physical life while the soul sails on an eternal journey.

This Issue

March 22, 2018

Hearing Poland’s Ghosts

‘I Should Have Made Him for a Dentist’