When people think of the work of Bob Fosse, Broadway’s foremost choreographer-director in the 1960s and 1970s, what they are likely to see in their minds is a group of dancers, in bowler hats and white gloves, standing in a stiff configuration and bobbing up and down in a cool sort of way. The dancers may rotate their wrists or splay their fingers, but they don’t stick out too many parts of themselves at one time, and they generally don’t travel around the stage much. They are often dressed in some combination of panties and garters and sheer silks; and even in the live shows, not to speak of the films, they offer you crotch shots galore. Not that they’re planning to do much with their crotches. Most of them would as soon knife you as go out with you. The sex is not sexual but satirical. It’s there to show us that every word we speak is a lie, that every promise will be broken.

That is what Fosse came to think about life, but even he was a child once. He was born in Chicago in 1927, the son of a salesman and a housewife, and he wandered into dance in what, for boys of the period, was the usual way, or the way they later claimed: his sister went to dance lessons, and he accompanied her. She quit; he stayed and became a star.

His teacher paired him with another boy in a tap duo called the Riff Brothers, and they played American Legion halls, amateur shows, and the like, until the other boy dropped out and Fosse went on, to TV—Your Hit Parade, The Colgate Comedy Hour, etc.—and eventually to small roles in movies. He loved dancing, and if you go to YouTube and search for “My Sister Eileen movie 1955, Alley Dance,” you can see this in a duet he performs with another man, Tommy Rall (Fosse’s the blond), both of them in hot pursuit of Janet Leigh. Even next to the excellent Rall, he’s clearly a virtuoso. Bell kicks, triple pirouettes, barrel turns, knee slides, back flips: he can do them all.

Nevertheless, he would have had a hard time making a career as a dancer. He was runty looking and stoop-shouldered, and he lost much of his hair as a young man. His looks also stood in the way of an acting career. His first big role was the lead in a 1951 summer-stock production of the Rodgers and Hart musical Pal Joey. If ever there was typecasting, this was it. Like Joey, a small-time nightclub emcee, Fosse could reel out breezy, lame jokes and get good-looking women to do him favors. This role, to which he returned many times, may have helped to form his rather sleazy personality, and vice versa.

The good-looking women were important. He was married by twenty, to the dancer Mary Ann Niles, and he soon had a useful girlfriend on the side, another dancer, Joan McCracken. (Of his love life, he said later, “I give my relationships two weeks now. Sometimes I bring it in ahead of deadline.”) Nine years older than Fosse and more sophisticated, McCracken nagged him to try for better roles, in film as well as theater, and to get some serious dance training, which he did, at the American Theatre Wing in New York, where he studied with Anna Sokolow, Charles Weidman, and José Limón.

McCracken also enthused about her boyfriend’s talents to the powerful producer/director George Abbott, who valued her opinion, and got him to go see Fosse in the 1953 film of Kiss Me Kate. Fosse’s role in that movie started small—he was just one of the Paduan skirt chasers—but its effect on his future was huge. The person in charge of the dances for Kiss Me Kate was Hermes Pan, Fred Astaire’s old collaborator. Fosse was desperate to make a dance for a movie, and he begged Pan to let him create just one number for Kate. Pan said okay, and Fosse made a dance to “From This Moment On,” and also performed in it. (Again, call it up on YouTube. Again, Fosse is the short blond.) From that moment on, exactly. The piece was high-flying, fun, crazy. Fosse got to choreograph Abbott’s next two big shows, The Pajama Game (1954) and Damn Yankees (1955).

Fosse had divorced Niles in 1951 to marry McCracken. A few years later, inconveniently, he found the woman who would become his greatest star and, presumably, his greatest love, Gwen Verdon. Verdon had been the protégée and assistant of Jack Cole, the inventor of what was then called “jazz dance.” She was a sexy redhead at the same time that she was sweet-spirited and comical, with an ear-to-ear grin. (“That alabaster skin, those eyes, that bantam rooster walk,” he said later. “Her in the leotard I will never forget”—a moving tribute.) In Damn Yankees she portrayed a devil intent on seducing the Washington Senators’ chief slugger, played by Tab Hunter in the 1957 film version. In her striptease, “Whatever Lola Wants,” she flings her garments this way and that over the Senators’ lockers as Hunter looks on, slack-jawed. The Senators won the pennant, and Fosse and Verdon became famous.

Advertisement

Fosse was by now very ambitious, and Verdon, who married him in 1960 (she got better than the two-week treatment, but not by much—they never divorced, though), was ambitious for him. Soon they embarked on a project, New Girl in Town (1957), that few other people would have dreamed of: a musical version of Eugene O’Neill’s Anna Christie. The main plot point of O’Neill’s play is that the heroine, after a number of years as a prostitute, tries to make a conventional marriage. The show included a dream sequence portraying an enthusiastic orgy in Anna’s old brothel. The producer of New Girl—George Abbott again—pronounced the orgy scene “just plain dirty” and ordered that it be taken out. There ensued a bitter fight, which Fosse lost, but which had a decisive effect on his career, because it convinced him that in the future he would be the director, not just the choreographer, of his shows. In other words, this man, who loved to shock and was used to indulging himself, would now have no rein on him, no one to tell him he had to tone something down.

On the contrary. It was at this time, the end of the 1950s, that Fosse went into psychoanalysis. (He would stay for five years.) His purpose, apparently, was to assuage his guilt over leaving McCracken for Verdon, and to calm his anxieties over becoming a director. The analyst prescribed for him some powerful drugs: Seconal to go to sleep and amphetamines (Dexedrine, Benzedrine) to wake up. The amphetamines, combined with the long, long hours of work that they supported—he rehearsed the dancers until they dropped—kept him in a state of sometimes irritable, sometimes euphoric hyperalertness. (He later did a lot of cocaine and, according to another biographer, Sam Wasson, gave it to some of his performers to help them fight off exhaustion: “‘The dressers would lay out your lines in your quick-change booth,’ one dancer said.”) Flying high, he did not mind scolding others for flying low—for not screaming, not taking drugs, not changing bedmates every two weeks. Such an approach may seem unnuanced to us now, but in the United States these were boom years for Freud’s reputation, and for the idea that getting naked meant telling the truth. Hair was less than a decade down the road.

At the same time that this boundary was being breached in his mind, so was another. In the early twentieth century, the major innovation in musical theater was the advent of realism, the elision of the song with the stage action. Before, the actors would be doing something or other; then, typically, they would stop and break into a song related to what they had been doing. Gradually, in the 1930s and 1940s, this changed. The song would grow out of the action. The actors would be admiring their cornfields or thinking about their nice new buggy, and then, as naturally as the choreographer could manage it, this would turn into a song, and maybe a dance, too.

But in the midcentury, as part of a ramping up of modernism throughout the arts, show dancing got tired of realism. As Fosse put it, “I get very antsy watching musicals in which people are singing as they walk down the street or hang out the laundry.” And so he took the step of acknowledging that the lyric situation of the show, its song-world, was different from its story. Indeed, he went in for forthright antirealism. Following Brecht and others, he used vaudeville techniques, film techniques, anything techniques. In his musical Sweet Charity, adapted from Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria (1957), he had his heroine, Charity, walk from one set into another without interrupting what she was saying. At the end of the show, her fiancé ditches her—pushes her into a lake—and Charity, played by the always-game Verdon, threw herself headlong into the orchestra pit. Fosse wasn’t pretending anymore that this wasn’t a show.

Those two developments, scabrousness and antirealism, were the two most important projects of Fosse’s middle period, his best period, and they are the main subjects of two new books about him: Kevin Winkler’s Big Deal: Bob Fosse and Dance in the American Musical and Ethan Mordden’s All That Jazz: The Life and Times of the Musical “Chicago.”

Advertisement

Winkler’s book covers Fosse’s entire career, and he may be the world’s best-informed person on that subject, since he spent almost two decades working for the performing arts division of the New York Public Library. (He also danced for Fosse briefly, in the ensemble rehearsals for a revival of the 1962 show Little Me.) After what must have been years in front of the NYPL’s videotape machines, he can describe, I think, every step that Fosse ever created. If, in a dance that the choreographer made for an Ed Sullivan TV special in 1969, Gwen Verdon raised her arms and turned her back and froze on count such-and-such, he can tell us about that, plus whatever came before and after. In fact, he could probably perform it. This does not always make for easy reading, but it is responsible scholarship, and it is going to be useful to researchers in the future. (Particularly that dance for the Ed Sullivan show: “Mexican Breakfast.” It was the basis for Beyoncé’s “All the Single Ladies” music video, which was named video of the year at the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards and has received over 640 million views in the version currently on YouTube.)

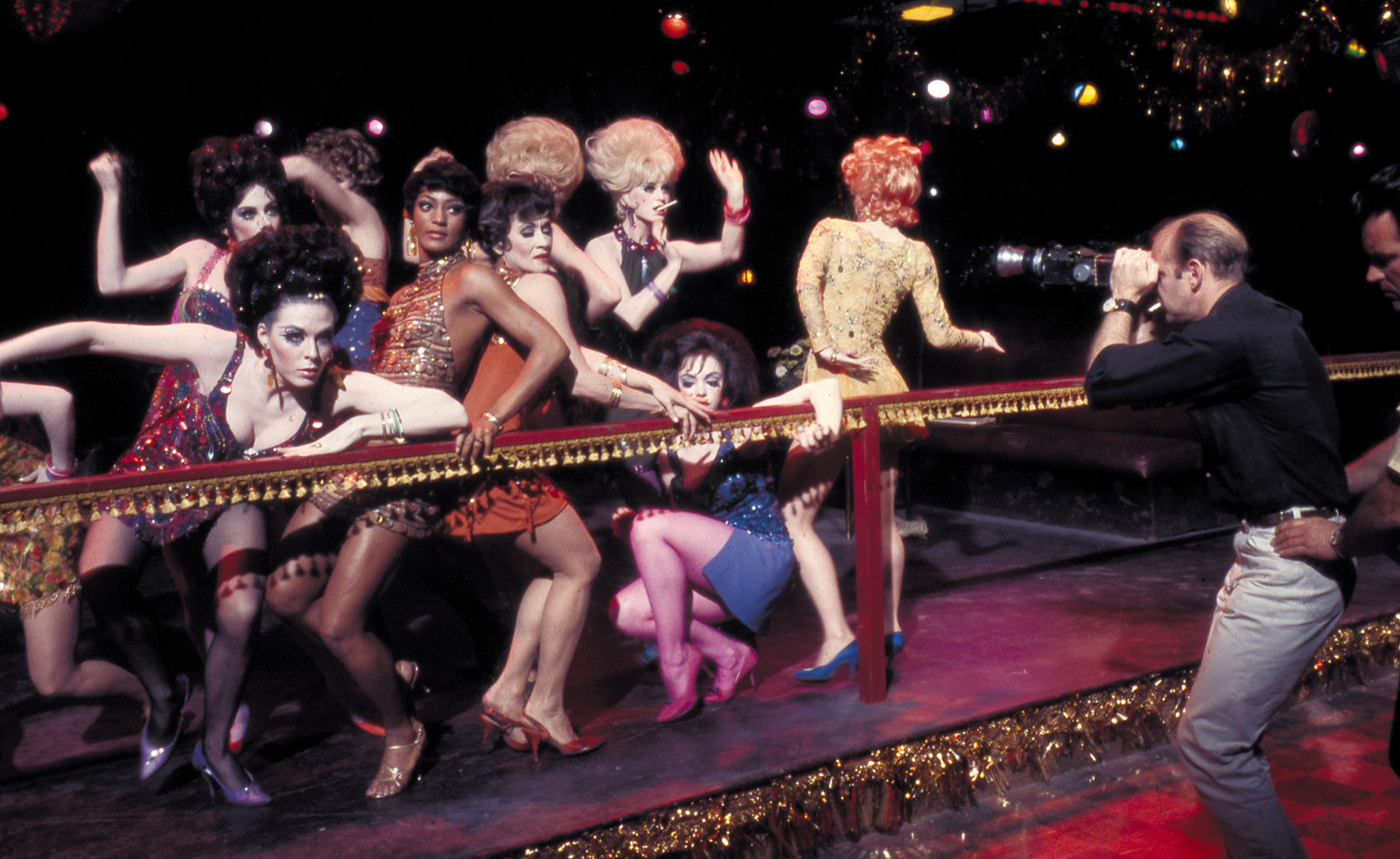

Apart from his mastery of detail, Winkler is our best source for what he thinks of as Fosse’s “conceptual staging”—that is, his attack on the fourth wall. Winkler believes that this starts in earnest in Sweet Charity. Charity is a “taxi dancer,” a woman who, in a special sort of club, will dance with you for a fee. (This is of course a metaphor for prostitution, and in Nights of Cabiria the heroine is a prostitute. The story was cleaned up for America.) The most interesting number in the show, at least insofar as the 1966 stage version was preserved in the 1969 film version, is “Big Spender,” in which a man enters such a club and confronts the dancers—a row of them, in a fantastic array of wigs and dangle earrings and whatnot—lined up behind a rail, waiting to be chosen. One beckons, “Hey, cowboy, you wanna dance?” Another slings her thigh over the rail and asks, “You got a cigarette for me?” Given the practiced coarseness of the routine—the frozen smiles, the squatty pliés—you don’t feel sorry for the women. Like so much middle-to-late Fosse, it’s not a representation of sex, but a representation of a representation of sex.

Fosse’s 1972 movie Cabaret shows a similar distancing. Cabaret grew out of Christopher Isherwood’s semi-autobiographical Berlin Stories, about a young tutor of English and Sally Bowles, a woman who, with little talent but great determination, is trying to make a go of it as the headliner in a seedy cabaret, the Kit Kat Klub, in Weimar-era Berlin. The story was later reborn as a play, then as a musical, Cabaret, directed by Hal Prince and set to songs by John Kander (composer) and Fred Ebb (lyricist).

Prince’s musical had a new tilt toward the unsayable—Nazism, violence, bisexuality—with, accordingly, newly indirect ways of addressing such matters. Once Fosse took over as director of the film adaptation, the material predictably became more sordid. To assemble his extras, Fosse got Verdon and his assistant director to cruise the dives of Berlin in search of faces that looked like something out of Georg Grosz or Otto Dix, and he instructed the Kit Kat Klub’s dancers to put on weight and stop shaving their armpits. At the same time, however, the presentation became more metaphorical. Most radical was Fosse’s decision to drop all but one of the songs that were not part of the Kit Kat Klub’s floor show. The remaining songs, because they were entertainment for a disreputable club, were almost all comic or obscene or both. But again, as in Sweet Charity, they were all to be seen as representations, performances, which made them seem more comic or obscene, but more coldly so. Think Jeff Koons.

As Cabaret is Winkler’s main exhibit, Chicago, the 1975 stage show with Gwen Verdon and Chita Rivera (not the 2002 movie with Renée Zellweger and Catherine Zeta-Jones, which many of us have seen, but not Fosse, who died in 1987)—is Ethan Mordden’s subject. Coming only three years after Cabaret, Chicago has a lot in common with it. Both of them deal forthrightly with vice, and both are tied to a very specific time and place—Cabaret to the 1930s in Berlin, Chicago to the 1920s in Chicago—a fact that, by giving historical underpinnings to the misdeeds, seems, at least superficially, to make some excuse for them. (“That’s the way Chicago was in the twenties.”) As the main characters of Cabaret are surrounded by crime and cynicism, and laugh at it sometimes, so do the people of Chicago, and not just sometimes.

Also like Cabaret, Chicago had a considerable prehistory before Fosse got his hands on it. The first version, a 1926 play based on true, or true-ish, events, concerns a pretty and not especially virtuous young woman, Roxie Hart. Roxie longs to perform in vaudeville, and she feels she has what it takes. Married to a man she considers a big nothing, she acquires a lover, Fred Casely, who promises to introduce her to important people in the theater, people who could help her. The show opens one night when, after a hasty, drunken copulation, Roxie reminds Casely of his promise, and he casually confesses that he lied. He doesn’t know any important theater people; he was just trying to get her into bed. He seems to think this was an okay thing to do. She doesn’t. She reaches for the gun in her chiffonier and plugs him full of holes.

In any other crime drama, the ensuing events would have been about Roxie’s trying to evade the murder charge. Not here. Roxie figures that her elimination of Casely might get her onto the stage. Innocent young woman, her morals undermined by booze and jazz, forced to kill the man who corrupted her: such a story, fed to the tabloids, might be just the thing to jump-start a vaudeville career. And that is the gist of the 1926 play, written by Maurine Watkins, a crime reporter for the Chicago Tribune, who had taken a playwriting course at Harvard. Watkins’s play was followed, in 1927, by a silent movie, Chicago, directed by Cecil B. DeMille, which Mordden finds dull, and then in 1942 by William Wellman’s excellent movie Roxie Hart, starring Ginger Rogers as Roxie.

Fosse knew all this history and for years had tried to buy the rights to Watkins’s play. She wouldn’t agree. From her youth, Watkins had been a devout member of the Disciples of Christ, a Protestant sect, and she was not ignorant of Fosse’s reputation; she thought he would turn her story into something dirty. Finally, in 1969, Watkins died, and in her will she took pity on the choreographer, in a roundabout way. She gave to Gwen Verdon the right of first refusal to the tale of Roxie. Of course she knew that Verdon was Fosse’s wife, but apparently she considered women more trustworthy. Verdon immediately turned the rights over to Fosse, and he proceeded to make something dirty, starring Verdon.

Mordden may know more about American musical comedy than anyone else on earth. His past works include When Broadway Went to Hollywood, on how Broadway song-writers fared in early song films; Anything Goes: A History of American Musical Theatre; Make Believe: The Broadway Musical in the 1920s; Beautiful Mornin’: The Broadway Musical in the 1940s; Coming Up Roses: The Broadway Musical in the 1950s; and On Sondheim: An Opinionated Guide, among others. And he doesn’t just know the musicals; he knows their contexts, their surroundings, item by item. In the case of Chicago, for example, he can list for you the city’s foremost crime neighborhoods (“Mother Conley’s Patch, Shinbone Alley, Little Cheyenne, the Black Hole, The Bad Lands, Satan’s Mile, Hell’s Half-Acre, and Dead Man’s Alley, among others”), the brothels that served them (Madame Leo’s, Monahan’s, French Em’s, Dago Frank’s, etc.), the items on the dinner menu of the fanciest whorehouse, the Everleigh Club (“from Supreme of Guinea-fowl to Spinach Cups with Creamed Peas and Parmesan Potato Cubes”), and so on.

Who cares? Mordden does, and you come to like him for it, a little. It gives his writing a pleasing relaxation. He loves these shows, they are his friends, and he joins in with them. “Roxie, close the door!” he yells at her at a certain point, while relating the events of DeMille’s movie. Someone is coming down the stairs. “Oh no,” he says, turning to us now. “Pallette’s body is in the way!” (Eugene Pallette is the actor who played the murder victim.) And in our minds, we try, with her, and him, to drag that big lummox out of the doorway. It’s like watching a child in front of a TV set trying to warn Bugs Bunny that Elmer Fudd is arriving with his shotgun.

Fosse’s Chicago was not a smash hit at the beginning. At the 1976 Tony Awards, it faced a formidable competitor, Michael Bennett’s A Chorus Line, to which it lost in category after category. Then, in 1996, as part of City Center’s excellent revival series, Encores!, it returned. Soon it moved to the Richard Rodgers Theatre, and in the twenty-odd years since, it hasn’t closed. It is now the second-longest-running show on Broadway, after Phantom of the Opera.

Mordden thinks that Chicago was born before its time—that the world had to get nastier before audiences could endorse Fosse’s cynicism. In particular, he thinks that the O.J. Simpson trial, with its parade of incompetence, showmanship, and bad faith, may have sparked the huge success of the Chicago revival. (It opened the year after the Simpson verdict was rendered.) At last, he says, the public found out that what Fosse was telling them about the connection between show business and the American justice system was the truth.

And that is Mordden’s main point about Chicago, that it is “commentative,” by which he just seems to mean satirical. God knows there were satirical musicals before it, notably Pal Joey (which, as noted, Fosse acted in a number of times) and also The Pajama Game (1954) and How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying (1961)—he was the first choreographer for both—and that’s not to mention the grandfather of the genre, The Beggar’s Opera (1728) and its descendant, The Threepenny Opera (1928). But none of these was as ugly-hearted as Chicago.

Mordden says that the show was Fosse’s farewell to Verdon. By now they had established separate residences. This was the last time she would be his star, and even then he had to bring in a second star, another boyfriend-killer—Velma Kelly, played by Chita Rivera—because Verdon, champ though she was, was fifty, and couldn’t have managed it alone. But, says Mordden, Fosse was not happy with the show. While he felt he had to give Verdon something, he resented having to do so, and he wanted Chicago nastier than he made it. In his original choreography, there was an orgy in the courtroom at Roxie’s trial. (The producers demanded its removal. It was only Jerry Orbach, who played Roxie’s greaseball lawyer, who got Fosse to take it out. Fosse respected Orbach, and Orbach told him that Brecht wouldn’t have done it that way.)

Fosse asked his musical collaborators, Kander and Ebb, to provide a really lame final number for Roxie and Velma, to show that these girls, though they killed their men to get into vaudeville, weren’t very good vaudeville performers. And the number that Kander and Ebb provided to Fosse’s specifications turned out so lame that he had to ask them to rewrite it. Even so, the resulting song—“Nowadays,” which they are said to have produced in an hour—is ambiguous. Things are terrific nowadays, Roxie and Velma say. You can get away with whatever you want. (“You can even marry Harry, but mess around with Ike.”) But somehow, they seem to feel, they aren’t having as much fun.

One interesting feature of the Winkler and Mordden books is how little they go in for biography. There was plenty of dirt to be had. Fosse reported how, when he went off to perform alone after the breakup of the Riff Brothers, he often worked in strip clubs, and how the strippers liked to take him on their laps and stick their tongues in his ears, among other things, so as to send him out on stage with an erection. I have two feelings about that. Imagine this thirteen-year-old boy ejaculating in his pants (he said he did) as he achieved what he thought was his dream. That could go a long way toward explaining how obsessed he was—morbidly, tediously—with sex throughout his life. Second, consider how afraid he must have been. “I was very lonely, very scared,” he said later. “You know, hotel rooms in strange towns, and I was all alone, 13 or 14, too shy to talk to anyone.” What did his parents think when he disappeared for days on end, saying he had to be in a show? Did they never think of going to the show? Of course, those were the days when people had big families—Fosse was the fifth of six children—and it was hard to keep track of what everyone was doing. Still.

In the last fifteen years of his life, things got tough for Fosse, and the spark that had enlivened Cabaret and Chicago dimmed. After Chicago he never again worked with a writer or with a first-rate score, and he never again had Verdon, that warm presence, on his stage. He made a number of movies: Lenny (1974), supposedly about Lenny Bruce but really about Bob Fosse, and then All That Jazz (1979), flatly about Bob Fosse, played by Roy Scheider. He used his daughter, Nicole Fosse, as one of the dancers; he used Jessica Lange, a recent girlfriend, as an angel who comes to visit him before his death. The labels on the hero’s Dexedrine bottles bore an address a few doors down from his own house, on West 58th Street. His last movie was Star 80 (1983), about a Playboy centerfold who was murdered by her husband. Anyone who wants to know the specifics can look it up on the Internet. It is appalling.

Fosse had a bleak ending. He retreated to his house in Quogue, on Long Island. He turned down offers to direct movies, such as Flashdance, that he would have been good at, and for which he would have made a lot of money. But he already had a lot of money, from shows like Dancin’, a 1978 anthology musical with, for example, a duet, “The Dream Barre,” in which the man slid his face under the woman’s dress as she did her barre exercises. Bernard Jacobs, the president of the Shubert Organization, accurately called this the “cunnilingus number.” But the problem wasn’t the unsexy sex, or not mostly. It was that, the 1960s and 1970s having passed, people began to notice that Fosse didn’t really have many steps at his command—characteristically, he acknowledged this—or, in the end, many emotions. He remained very influential. In the 1980s, you could barely see a dance in a music video—let alone a TV commercial or a Cirque du Soleil number or a dancercise routine—that wasn’t filtered through his style. But an influence is not necessarily a good influence.

And by now, four decades after the 1980s, you may ask yourself what the difference is between this work and a Vegas floor show. Winkler is not afraid of the question. He flatly says that some of Fosse’s product is leering, tawdry, crude. At the end of All That Jazz, there is a number called “Bye Bye Life,” in which Joe Gideon’s death is played against the Everly Brothers’ sweetly anodyne “Bye Bye Love.” Winkler writes:

It is Fosse’s comment on both his fears of being second-rate and his cynicism about his ability to manipulate an audience. “I hesitate about a movement and think: ‘Oh no. They’ll never buy that. It’s too corny, too show-biz.’ And then I do it, and they love it.”

So he does it again, and he hates himself, and hates them.

In 1987, at the age of sixty, while walking down the street with Verdon—they were on their way to the opening of a revival of Sweet Charity—Fosse had a heart attack, his second. He died in the hospital emergency room. For his reputation’s sake, this was not a moment too soon.

This Issue

May 24, 2018

Crooked Trump?

Freudian Noir

Big Brother Goes Digital