What did Doris Lessing mean when she called Anna and Molly in The Golden Notebook “free women”? Certainly not that they were happy. The two friends, living in late-1950s and early-1960s London without men, supporting themselves through their art, devoting themselves to politics, still wish to be married. Regarded by generations as a bible of women’s liberation, The Golden Notebook was Lessing’s breakout work, a complex and shifting account of a woman making a life for herself among the competing ideologies of the 1960s. When it opens, Anna Wulf has written a novel that pays her bills, has had affairs and adventures, has fought racism in Africa, has a child. She knows that her independence comes at the price of her happiness, and that happiness, which for her means love, would cost her her mind. Lessing later said that “Free Women”—how she named the five chapters about Anna and Molly’s lives, which are interspersed with excerpts from Anna’s notebooks—was “an ironical title.”

“Men. Women. Bound. Free. Good. Bad. Yes. No. Capitalism. Socialism. Sex. Love…” The themes of The Golden Notebook are introduced baldly, “with drums and fanfares,” yet the conclusions Lessing draws from them are tangled, even fifty years after the novel’s publication. Anna is self-sufficient but emotionally dependent. Sex is a bind. She hates the sense of reliance it creates but cannot avoid it. And what of the men she falls in love with? Even the intensity of her attraction to Saul Green, the American radical based on the writer Clancy Sigal, can’t obscure his awfulness: “He talked—I…realised I was listening for the word I in what he said. I, I, I, I, I—I began to feel as if the word I was being shot at me like bullets from a machine gun.” (Raging male insecurity was a specialty of Lessing’s.)

Molly and Anna have agreed to this life. They frequently confirm this to each other. “We’ve chosen to be free women, and this is the price we pay, that’s all,” says Ella to Julia in a novelization of their relationship that Anna writes in one of her notebooks. But political emancipation does not ensure joy:

Both of us are dedicated to the proposition that we’re tough…. A marriage breaks up, well, we say, our marriage was a failure, too bad. A man ditches us—too bad we say, it’s not important. We bring up kids without men—nothing to it, we say, we can cope. We spend years in the communist party and then we say, Well, well, we made a mistake, too bad.

Unlike The Feminine Mystique, published the next year, The Golden Notebook did not promise happiness for women in work or collective action. Molly and Anna get out of the house; they support themselves. They go to meetings and to parties. They don’t spend all day reading House and Garden. Still, they suffer from “the problem with no name.” “Women’s emotions are all still fitted for a kind of society that no longer exists,” thinks Ella. “It’s possible we made a mistake,” says Anna. They live the lives they want, which must be its own reward.

“It seemed that Lessing was a writer to discover in your thirties; a writer who wrote about the lives of grown-up women with an honesty and fullness I had not found in any novelist before or since,” Lara Feigel writes in the opening pages of her memoir Free Woman: Life, Liberation, and Doris Lessing. Feigel, the author of books about artists in London and Berlin around World War II, returns to The Golden Notebook during summer wedding season. After “white weddings, gold weddings; weddings in village churches, on beaches, at woolen mills,” she finds herself wondering: Is this it? Why do her friends seem so eager to throw their selves away for a man or a family? “They began by identifying as part of a couple and then once a child arrived they identified themselves primarily as mothers.” She is happily married and trying for a second child. Yet she begins to resent “the apparent assumption that this remained the only way to live.”

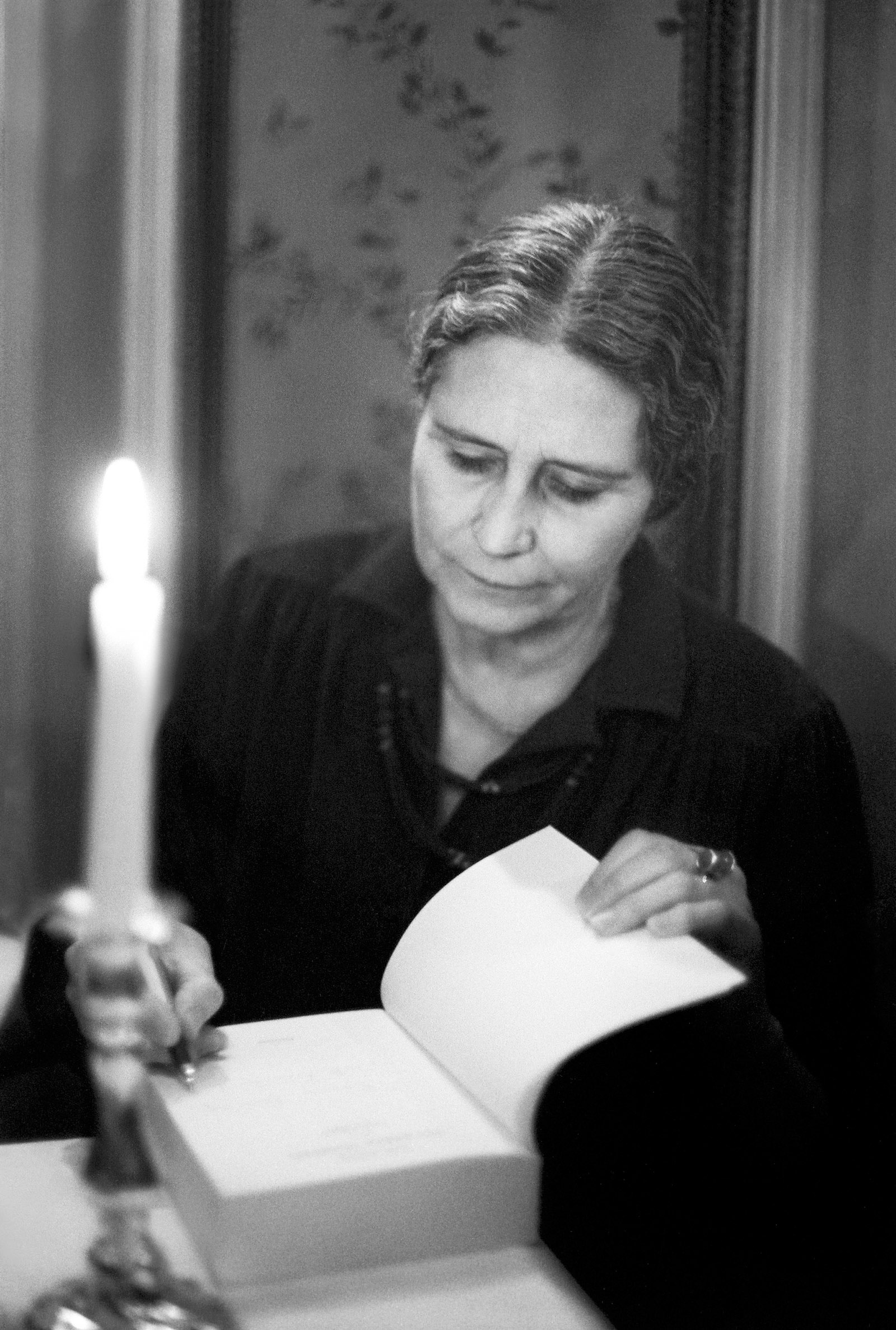

Lessing, Feigel hopes, will teach her how to find freedom, a word she leaves enticingly vague. Sitting under “a hundred metres of tasteful Liberty print bunting,” she hears Anna’s pronouncement from the beginning of The Golden Notebook: “I am interested only in stretching myself, in living as fully as I can.” Lessing wrote the novel in her early forties while living with her son and friends in London. She had recently left the Communist Party; her years fighting apartheid in South Africa were long behind her. Could the writer guide Feigel to a life outside convention? “I wanted to learn from her how to stand in the bush looking up at the sky and to liberate myself from the conflicting desires that stopped me being free.”

Advertisement

I imagine I am not the only reader who paused a little here. Single life, gay marriage: choices that would have seemed daring in Lessing’s time are unremarkable today. A life lived without a partner is no longer a form of social defiance. For a large number of people, it’s just the way things are. Still, even by today’s standards, Lessing’s life went against convention. She married twice and had many affairs. She wrote frankly about sex. Most pressingly for Feigel, she abandoned two of her children in Africa so that she could live and write in London.

Lessing never apologized for the choices she had made, but she never seemed quite settled with them either. “I did not feel guilty,” she said about the eight- and nine-year-old she left behind in Africa. She also said, “I know all about the ravages of guilt, how it feels, how it undermines and saps. I energetically fight back. Guilt is like that iceberg, but I’d say with ninety-nine hundredths hidden.” As she wrote in her memoir, she told her children that she was leaving for their own good:

I explained to them that they would understand later why I had left. I was going to change this ugly world, they would live in a beautiful and perfect world where there would be no race hatred, injustice, and so forth. (Rather like the Atlantic Charter.)… One day they would thank me for it.

She continues, “I was absolutely sincere. There isn’t much to be said for sincerity, in itself.”

Her own politics wavered, driven by anger, experience, and also self-righteousness. She was a staunch Communist. She became disillusioned and railed against the party. In The Golden Notebook she described in great detail women’s state of confinement. When the book was praised by feminists, she called the concerns of the women’s movement “small and quaint.” Jenny Diski, who lived with Lessing as a teenager, describes in her memoir how Lessing shuttled from communism to psychoanalysis to Sufism, each time looking for a totalizing system to contain her thoughts. A fear of an imminent apocalypse often had something to do with it. (“She said I shouldn’t tell a mutual friend of ours about the forthcoming end of the world,” Diski writes, “because it would be hard for a ‘young woman with a baby to take it.’”) Lessing’s works, wrote John Leonard in these pages, “add up to one big bill of indictment, one long history of disenchantments, and fifteen rounds with a heavyweight reality principle.”* She believed what she believed and then she moved on.

Like recent literary memoirs such as Rebecca Mead’s My Life in Middlemarch and Bee Rowlatt’s In Search of Mary: The Mother of All Journeys, Feigel examines Lessing primarily through her own experiences, an approach that introduces Lessing to a new audience and dulls her edge. The genre of the “bibliomemoir” has grown in recent years, in part because its combination of close readings and contemporary inquiry often leads to new and lively interpretations of classic works. (Though just as often, this gives the impression that books only have literary value when the situations they describe closely match those of the memoirist’s own life.)

Feigel reads thoroughly and carefully. In one passage she dissects Lessing’s writing on her body. “There is no exultation like it, the moment when a girl knows that this is her body, these her fine smooth shapely limbs,” Lessing wrote. But sex brought with it emotions that often seemed to entrap her. “Does freedom lie in escaping biology or in succumbing to it? In having sex or avoiding it?” asks Feigel. “For me, as for Doris Wisdom, it was not enough to leave girlhood behind. Womanhood did not generously proffer the freedom it had promised.”

She goes to see Clancy Sigal to ask him about his time living with Lessing. Dressed in shorts and a cap that says “Secret Agent,” he tells her that he’s never read anything Lessing’s written. “She was a highly intelligent, highly literate, highly sexed woman, and here was I, this lumbering, non-writing Yank, the only thing going for me was I was sexy, but I didn’t treat her any differently from how I treated women in America.” His current partner offers her a possible consolation prize: “We have some of her ashes in the living room!”

Feigel reads about the Communist Party and marvels at Lessing’s devotion to it. Lessing, active in the party long after revelations of Stalin’s crimes, didn’t leave until the invasion of Hungary in 1956. She felt “very shattered” by Arthur Koestler’s revelations about Stalin’s purges in The Yogi and the Commissar, but then concluded that he had been biased. “I was shocked by her attempts to defend Stalin and his regime in the face of such incriminating evidence,” writes Feigel. “But I envied the love affair” with politics. By contrast, she feels that the politics of her generation are tame. “Radical politics had become less possible, and it seemed to make us less passionate.” One suspects that she spends little time with environmental activists or leftists.

Advertisement

Feigel calls herself “old-fashioned” and marvels at her own timidity in the face of possible experimentation. A passing reference to “the queer world” makes it seem very distant indeed. She writes:

Once sex before marriage, abortion and divorce had become more widely accepted, once women had greater opportunities for education and employment and were aided domestically by the input of “new men,” there was less need to seek freedom in radically different forms of life of the kind proposed by communism or by the first forms of feminism.

Yet it is because of progressive movements that households have changed and new forms of coupling are possible. The transformations of family structure since the 1960s go largely unaddressed in Free Woman.

More than Lessing’s adventures, what comes across most strongly in the book is Feigel’s sensitivity and thoughtfulness. She seems disappointed that she could not live the life that Lessing led and that she does not even want it. Curious about Lessing’s friendship with the psychoanalyst R.D. Laing, she decides to try talk therapy. She quits after two sessions. She is interested in drugs but doesn’t take any. “I was too anxiously attached to the present configuration of my brain to try LSD in the interests of research.” She talks about divorce with her husband, but doesn’t act on it. Polygamy turns her off. “I might have been more enthusiastic if I’d been living in California,” she jokes. She buys a house in Suffolk with a friend and spends time there, writing alone. “I was amazed that life should turn out to be this simple; that freedom should reside in so bourgeois an acquisition as a second home.” One unspoken source of freedom: money. Lessing bought a house in central London on the royalties from The Golden Notebook. Could a writer of literary fiction do the same today?

In the end, Feigel finds she can no longer see “freedom as an attainable goal in life.” What she wants instead is honesty and peace. Writing may be the best and most reliable source of personal emancipation, better than any specific life choice. Lessing wrote: “I was able to be freer than most because I am a writer, with the psychological make-up of a writer, that sets you at a distance from what you are writing about.” Feigel, too, has learned to write about herself without inhibition. In a brief, sad afterword, she writes that while she was finishing the book, her husband left her for another woman shortly before she became pregnant with their second child:

I am tied to this new creature by the kind of love that makes freedom seem less urgent…. Now, unable to leave the house without my child, unable to quest after new places or new lovers, I do feel freer than I did in the period described in this book. I think this is because I have become more honest and because I have discovered that it’s possible to live and to write honestly even in the public sphere, even at the risk of shame.

Her life as a free woman has finally begun.

One handicap of the bibliomemoir is that it rarely delves into the books at hand. The pages must compete with the ups and downs of lived experience. Yet to my mind what’s most interesting about The Golden Notebook is its shape: how it moves and twists through the notebooks that Anna keeps, so that the ground always seems to be shifting. It’s a form that, to me, seems particularly well suited to writing about women. As Anna regularly thinks, women in a male society often find themselves cast into “roles”: the “leader’s girl friend,” “the free woman.” It is perhaps for this reason that the book seems to anticipate so much of the novelization of women’s lives in the past several decades by authors like Sheila Heti, Rachel Cusk, and Annie Ernaux, in whose works a precise accounting of emotions suddenly crashes against the sharp edge of social status.

In one scene, Molly and Anna marvel that men call them up whenever their wives are out of town: “Free,” says Julia. “Free! What’s the use of us being free if they aren’t? I swear to God, that every one of them, even the best of them, have the old idea of good women and bad women.” It reminds me of a scene in Happening, Annie Ernaux’s novel about her abortion in the early 1960s. The pregnant protagonist goes to the home of a man she knows to get his advice. He is married and a member of an underground contraceptive group. While his wife is out of the house he gropes her: “Jean T kept pressing into me while he was drying the dishes. Then suddenly he resumed his normal tone of voice and pretended he was just testing my moral strength.”

Unlike much autobiographical fiction, however, The Golden Notebook never gels into a single alternate account. Lessing’s formal innovation means that there is no “real” Anna to compare to the social Anna. No single intimate self challenges her outward presentation; there’s no one mind, simmering against the aggressions of the world, that is finally released here. In one notebook we have political Anna, then in another Anna the lover and in a third Anna the writer and then Ella as Anna, who thinks that “obviously, my changing everything into fiction is simply a means of concealing something from myself.” Which is the real one? All of them and none of them:

That Anna, in that time, was such and such a person. And then, five years later, she was such and such. A year, two years, five years of a certain kind of being can be rolled up and tucked away, or “named”—yes, during that time I was like that. Well now I am in the middle of such a period, and when it is over I shall glance back at it casually and say: Yes, that’s what I was. I was a woman terribly vulnerable, critical, using femaleness as a sort of standard or yardstick to measure and discard men. Yes—something like that.

Lessing would later say that with the form of the book she wanted to fight atomization, the division of the novel and of life into discrete parts that distorted the whole. “The book is alive and potent and fructifying and able to promote thought and discussion only when its plan and shape and intention are not understood,” she wrote. For the reader, it has a more immediate and less theoretical effect: the ability to capture the odd experience of being a person in the world.

Rereading The Golden Notebook, I noticed some ugliness I had not remembered. For one thing, there was Lessing’s homophobia, her insistence on “real men,” and her cruel descriptions of the two gay men whom Anna keeps as lodgers. There were her odd, rigid views about sex. She believed, as Feigel discusses, that only a vaginal orgasm could prove a deep connection between a man and a woman, a view shared by Freud. Clitoral orgasms, by contrast, were “a substitute and a fake.”

Yet so much remained fresh, often surprisingly so. Moving as it does from one Anna to the next, the book allows for a strangely generous form of coexistence. The inconsistencies of the self splay out without muddling into a single story. Freedom and loneliness are both present. Radicalism and personal isolation are too. It is true that Anna and her friends have been disillusioned with what they’ve been able to accomplish. Yet Anna believes that

every so often, perhaps once in a century, there’s a sort of—act of faith. A well of faith fills up, and there’s an enormous heave forward in one country or another, and that’s a forward movement for the whole world. Because it’s an act of imagination—of what is possible for the whole world. In our century it was 1917 in Russia. And in China. Then the well runs dry, because, as you say, the cruelty and the ugliness are too strong. Then the well slowly fills again. And then there’s another painful lurch forward.

Moments later, the character she’s been talking to tries to kill himself.

What to make of such moments? Freedom in Lessing’s novels “is allowed to be contradictory,” as Feigel writes. It can remain unresolved without losing any of its urgency. Activism is usually progressive and idealist; personal lives are often grasping and reactionary. Both have their own logic. The Golden Notebook allows for the fact that the hope for progress, and the work it requires, can clash with the realities of life and still have worth.

After all, politics is a slog and often feels pointless. Meanwhile, time passes and you get older. The problems of the world seem to hover in a frightening and scary way. “It could be a Chinese peasant,” says Anna when explaining her writer’s block. “Or one of Castro’s guerrilla fighters. Or an Algerian fighting in the FLN…. They stand here in the room and they say, why aren’t you doing something about us, instead of wasting your time scribbling?” But good work takes a long time, even if every day the outside world gets a little darker. What can you do? Love, work, and live as fully as you can.

This Issue

September 27, 2018

Aquarius Rising

Missing the Dark Satanic Mills

Tenn’s Best Friend

-

*

“The Adventures of Doris Lessing,” The New York Review, November 30, 2006. ↩