This March, in a four-part series on Fox News called “Men in America,” Tucker Carlson sat in front of the American flag and listed a set of downward trends for men in school, work, and emotional well-being. Compared to girls, Carlson told viewers, boys far more often fail in school, are diagnosed with ADHD (and take medication for it, which carries a risk of depression later in life), play video games, become overweight, lack a driver’s license, get addicted to alcohol or opioids, become mass shooters, commit other felonies, go to prison, and die of drug overdose or suicide. In 1970, 58 percent of undergraduates in four-year colleges and universities were male; by 2014, that had fallen to 43 percent. Women earn more doctoral degrees than men and are now a majority of those entering medical and law schools. Young single women are two and a half times more likely than single men to buy their own homes; single men more often live with parents.

A recent book not mentioned by Carlson, The Boy Crisis: Why Our Boys Are Struggling and What We Can Do About It, by Warren Farrell and John Gray, gives another set of such statistics. In high school, boys receive 70 percent of Ds and Fs, are more likely than girls to be suspended, and are less likely to graduate or be chosen as class valedictorian (70 percent of whom are girls). Other research shows that boys are less likely to enjoy school or think grades are important.1

Carlson complained that the media have been silent about these problems. He blamed this on public figures who he thinks focus too much on women: Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, the Democrats, and the faculties of “liberal” university-based gender studies programs. (Carlson’s series ran during Women’s History Month.) In support of this view, he consulted the provocative and popular University of Toronto clinical psychologist Jordan Peterson, who insisted that any talk of “equity, diversity, inclusivity” should be considered “indoctrination” and reason to withdraw a boy from any school with a curriculum in which such words appear. Manhood, both Carlson and Peterson have suggested, is something that liberals disparage and conservatives protect.

Carlson omitted to say that, as of 2016, women earn 80.5 cents to every dollar a man earns for year-round full-time work (a gap that increases as level of education rises), and that two thirds of minimum-wage workers are women. Men’s college enrollment is still on the rise—that is, relative to female BA-holders, males have declined since 1970, but relative to their male counterparts in 1970, a higher proportion of men hold BAs today. Carlson also largely ignored differences in class and race that exacerbate those of gender. As the MIT labor economist David Autor and his coauthors found in a study of Florida brother-sister pairs, the gender gap in school performance is wider among the poor than the rich. Boys born to mothers with lower education and income got lower grades, relative to their sisters, than boys born to more highly educated and affluent mothers.

Still, we can’t dismiss such statistics as a hyperbolic reaction to feminism. In the last three decades, the lives of men have undergone what Autor and coauthor Melanie Wasserman have called a “tectonic shift.”2 Compared to women, a shrinking proportion of men are earning BAs, even though more jobs than ever require a college degree, including many entry-level positions that used to require only a high school diploma. Among men between twenty-five and thirty-four, 30 percent now have a BA or more, while 38 percent of women in that age range do.

The cost of this disadvantage has only grown with time: of the new jobs created between the end of the recession and 2016, 73 percent went to candidates with a BA or more. A shrinking proportion of men are even counted as part of the labor force; between 1970 and 2010, the percentage of adult men in a job or looking for work dropped from 80 to 70 while that of adult women rose from 43 to 58. Most of the men slipping out lack BAs. We have yet to fully address these changes, and there’s no reason we can’t do so while also celebrating the successes of American girls and women.

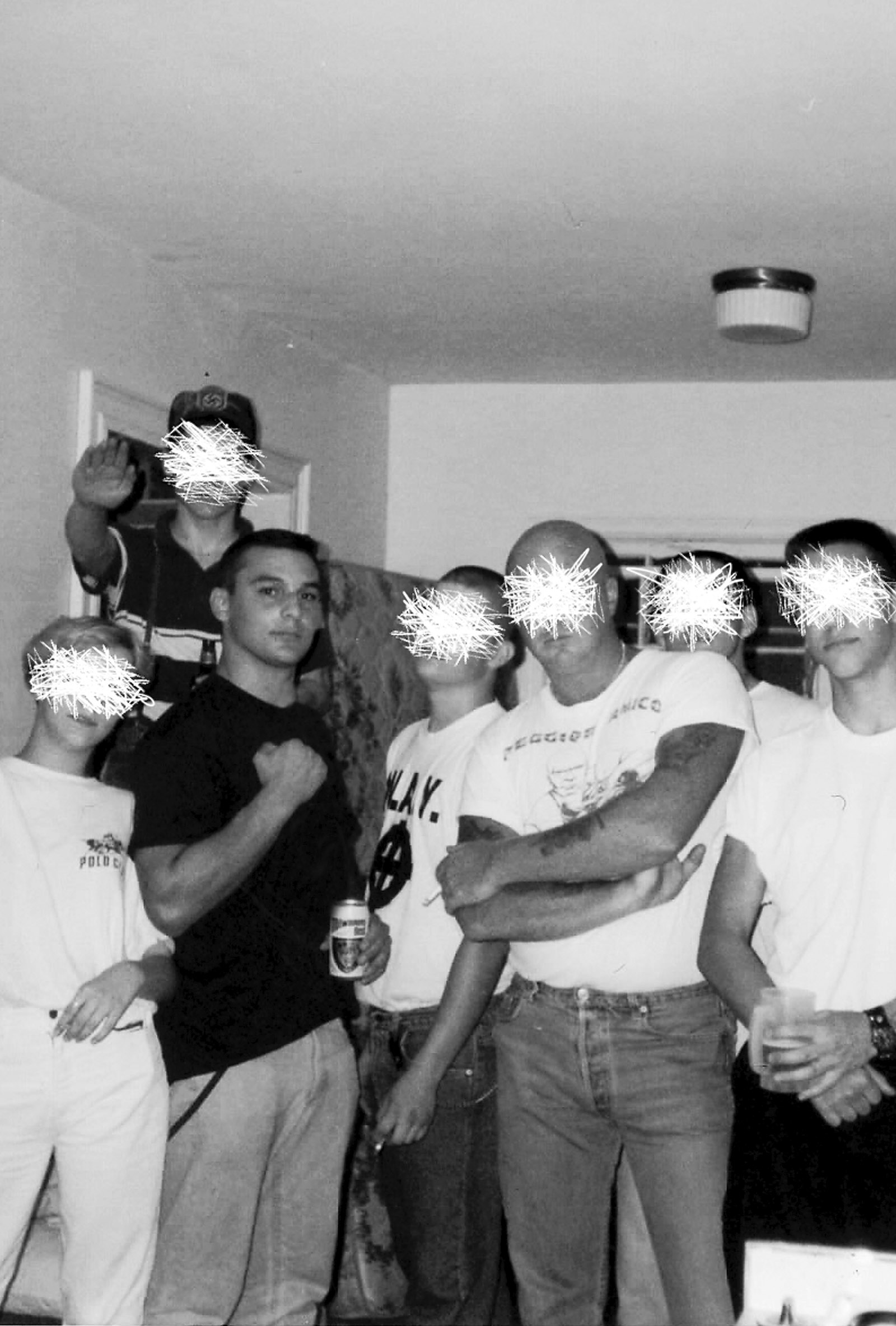

Andrew Moisey

Fraternity brothers at the University of California, Berkeley, 2006. The photograph is by Andrew Moisey from his book The American Fraternity: An Illustrated Ritual Manual, which contrasts fraternities’ constitutions, oaths, and rituals with photographs revealing their often underlying violence and misogyny. It is published this month by Daylight.

Warnings of the trouble facing boys are not new. In 1999, the Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Susan Faludi brought the male predicament to public attention with her compassionate book Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man.3 In it, she argued that displaced craftsmen, combat veterans, troubled “bad boys,” and other men had come to feel that, in the world they were supposed to own and run, the values of diligence, integrity, and loyalty no longer mattered. But the very “paradigm of modern masculinity”—that men are masters of their fate—prevents men, she argued, “from thinking their way out of their dilemma.” Powerful social and economic shifts, the impact of which remains unacknowledged, have “a lot more to do with [male] unhappiness,” she wrote, “than the latest sexual harassment ruling.” The first serious classroom explorations of manhood emerged in the courses Peterson seems to deride, offered by scholars like Michael Kimmel, the foremost sociologist of American masculinity, whose books Guyland (2008) and Angry White Men (2013) predate Carlson’s warnings, and whose important and moving newest book, Healing from Hate, connects the male crisis with hate crimes.

Advertisement

Nor is there much new about the charge that Americans have been “indoctrinated” to ignore the problems of men. In his 1993 best seller The Myth of Male Power: Why Men Are the Disposable Sex, Farrell, who had once been a prominent supporter of the feminist movements of the 1970s, argued that feminism had turned men into second-class citizens. Kimmel has called that book the “bible” of many of today’s men’s rights activists; Peterson has cited Farrell as an influence.

In The Boy Crisis, Farrell and Gray (the author of the 1992 book Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus) concentrate on what they consider a primary cause of the problems facing men: declining contact between boys and their fathers, an unintended consequence of America’s high rate of divorce. Some children of divorced couples live with a stepdad, but two thirds of those marriages dissolve. For a period after their parents’ divorce, boys are especially prone to depression and show more aggressive behavior.

In an appendix enumerating the benefits of good and present fathers, the authors include a heightened capacity to empathize, to delay gratification, and to avoid being bullied or becoming a bully. One study of factors that inhibit teenage delinquency found that the sheer “presence” of a dad—being on call—mattered more than his financial support or even “involvement with” (playing with or reading to) his son. Farrell and Gray concentrate on biological dads in traditional marriages, but other research has shown that stepdads benefit boys too. One large quantitative study found, surprisingly, that the presence at home of a stepdad inhibited male delinquency even more than that of a biological dad.

The Boy Crisis is an advice book for parents, so chapters are short and pages studded with boldfaced topic headings: “The Male Hero’s Kryptonite,” “What Happened to Pickup Team Sports?,” “The Power of Purpose.” The reasoning can be simplistic: “Dads who nurture dad-enriched children receive the gift of a nurtured soul.” And given Farrell and Gray’s focus on the father-son bond, it’s curious how little attention they give to class and race, for it is in poorer families that that relationship is more often troubled or absent. One study tracked changes between 1960 and 2010 for white men between ages thirty and forty-nine. In 1960, the family lives of those in the top 20 percent and bottom 30 percent of the class ladder were fairly alike; 94 percent of the top and 84 percent of the bottom were married. But by 2010, a dramatic split had appeared; at the top 83 percent were married, but at the bottom only 48 percent were. A troubling cycle is set in motion: sons of fading fathers, studies suggest, especially fathers with a high school education, are more likely to become fading fathers themselves.

In some ways, the experience of children in low-income white families has come to resemble that of those in many African-American families. From 1970 through 2014, the proportion of white children living with a single parent rose from 10 to 19 percent, while that of black children rose earlier and higher, from 35 to 54 percent. These statistics show, among other things, the disproportionate effects of mass incarceration, which has separated many black children from their fathers. Today, three quarters of white children live with two married parents, while a third of black children do.

I recently asked Mike Schaff, a Cajun from Bayou Corne, Louisiana, whom I’d interviewed for a book on the far right, for his thoughts on the state of manhood today. Now a sixty-nine-year-old retired oil worker, a Fox News watcher, and a Trump voter, Mike felt Carlson “had a point”—these were tough times for men, more so than when he was a boy, shooting crows in the sugar cane fields and setting crawfish traps with his strict but loving dad, a plumber. Nowadays, marriage and a steady father figure were less certain (he was on his third marriage, and has had no children). Less certain, too, was respect for the male role of protector. “We men rescue women and children first and put our own lives last,” he said. “In war, men risk their lives for wives and children. As policemen and firefighters, we protect the public.”

Advertisement

Mike felt like his family’s protector. He owned four guns, which he was prepared to use “if things got worse.” But did women still need a man’s protection? Did they need, as they used to, a man’s financial support, a man’s conferral of status in marriage, or even his traditional part in procreation itself? Not so much. Mike’s wife earned more than he did, and had a higher level of education. Since his stepdaughter, a single mother, had suffered several upheavals in her life, and since his wife was still working, Mike had recently taken on weekday care of his newborn step-grandson, bottle-feeding and changing diapers.

Farrell and Gray call for a world in which fathers deeply involve themselves in the lives of their children, a goal most feminists heartily embrace; indeed, a vast number of articles and books—my 1989 book The Second Shift among them—have been devoted to men’s involvement in the lives of their children and at home. Between 1989 and 1999, no fewer than two hundred social science studies focused on this. For decades, talk was of “the new man.”

Peterson, and to a lesser degree Farrell, critiques “feminism” for ignoring the importance of fathers. The Boy Crisis authors offer one possible solution to both the needs of sons and the desire and willingness of wives to support the family: the stay-at-home dad. Such an option still challenges the prevailing notion of male status. But in an interview with Peterson, Farrell explained how we might elevate the status of the stay-at-home dad using the same social bribes that persuade men to sacrifice themselves in war: men want to be heroes, the authors observe, so the culture needs to make it heroic to be a great dad.

In our conversations, Mike strongly condemned white supremacy and misogyny. But some of his neighbors condemned these views less strongly and knew others who approved of them. In Healing from Hate, an illuminating book building on over twenty years of thinking and research, Michael Kimmel shows that the boy crisis provides fertile ground for recruiters from white supremacist, neo-Nazi, and other extremist groups. According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, the number of hate groups rose from 784 in 2014 to 954 in 2017. The center’s list now includes “male supremacy” hate groups such as Return of Kings and A Voice For Men, which characterize “all women as genetically inferior, manipulative and stupid and reduces them to their reproductive or sexual function.”

Alek Minassian, the man who drove his van into pedestrians on a Toronto street in April, killing ten, declared himself an “incel,” a member of an online community of “involuntarily celibate” men who consider themselves the victims of women who decline to sleep with them. His rampage was pledged to the “Incel Rebellion”—a backlash against feminism, but also against the social hierarchy in which conventionally attractive and successful men, “Chads,” have greater access than other men to sex and the affection of women. The rise of such groups is a threat in itself, but it also reveals a close link between violent extremism and misogyny.4

Of those Kimmel profiles—members or ex-members of male hate groups in the US, as well as former members of hate groups in Germany, Sweden, Great Britain, and Canada—virtually all were abandoned by their fathers or “were abused, physically or sexually, by stepfathers or mothers’ boyfriends.” Fathers who were present, he says, were “emotionally shut down, opaque, phantom presences in their own homes.” Many of these sons were bullied or became bullies on the playground. One man told Kimmel he grew up in a “field of violence” that kept him “constantly enraged.”5 Such a boy then links the harshness and indifference he encountered with his identity as a boy, so that he believes he is being punished for being male. “Whether I was talking with ex–neo-Nazi skinheads in Sweden, ex–white supremacists in the United States, or even ex-jihadists in London,” Kimmel writes, “the issue of masculinity…did not fail to come up.” Failed by men—presumably mothers played some part, though we hear little about it—the men he studied also felt like “failures as men.”

Men don’t need women to recognize their manhood, Kimmel argues; they need other men. “Women would pollute things,” he was told. Generally women are badly treated by white supremacist groups; in the US few accept women as equal members. A number of white supremacists call for “tradwives”—traditional wives—to produce more white children. The men in neo-Nazi groups shave one another’s heads and dress alike in black, tattoo their arms, and wear battle-ready, hard-toed, thirty-two-eyelet boots. Male-to-male initiations into hate groups also called for “minor vandalism” for which they would be “declared heroes,” Kimmel observes wryly, such as painting swastikas on Jewish tombstones. “Men need a glorious war against something,” the historian George Mosse observed of German extremists in the 1930s, so that they can display their masculinity “stripped down to its warlike functions.”

In his autobiography White American Youth, Christian Picciolini offers a vivid illustration of the path to extremism Kimmel describes. Born in 1973 to blue-collar Italian immigrant parents who worked long hours in Oak Forest, Illinois, Picciolini recalls his father as being quick with undeserved smacks to the head and otherwise as an impassive chauffeur driving him to be placed in “someone else’s care.” A short boy with a funny name, Picciolini became the playground target for bullies, until he developed a vicious punch of his own. He carried guns, drank, and listened to harsh music from bands with names like Skrewdriver, Brutal Attack, Skullhead, and No Remorse.

It was a fatherly gesture from a neo-Nazi that first drew the fourteen-year-old into an extremist worldview. Picciolini was smoking a joint with a friend when he was spotted by a sharp-jawed, bulky man sitting in a car. The friend ran away. Christian stood his ground. The man rose from his car, walked over to Christian, took the joint from his mouth, and told him that he shouldn’t succumb to a Jewish plot to sedate Gentiles.

In his new life of white supremacy, Picciolini began to “succeed.” He wrote and performed songs—one of which Dylann Roof listened to in 2015 a few months before killing nine black churchgoers in Charleston. He started a business selling violent music and launched a band that performed at white power rallies around the world. At sixteen, he led Hammerskin Nation, which the Anti-Defamation League described as the “most violent and best-organized neo-Nazi skinhead group in the U.S.” Picciolini was living out a strange, toxic inversion of the American Dream.

But when his wife became pregnant, “I suddenly felt guilty and out of sorts,” he recalled. “I didn’t respect…the Klansmen,…the mother carrying her infant with a tiny Klan hood on.” Becoming a father turned Picciolini’s life around, but he acknowledges that this came at the expense of his teenage wife’s own ambitions: “She sobbed. What about her plans? What about college? What about becoming a teacher?” That trade-off is not incidental. Kimmel found in his research that

for several it was a wife, girlfriend, their mother, or another woman who drew them away from the movement. It’s often through personal relationships with women that the guys get enough strength to tear themselves away. It’s hard. It was the intensity of the male bonds that got them in. That intensity has to be matched—or even exceeded—by the relationships with women.

Like millions of girlfriends and wives, Picciolini’s wife made enormous hidden sacrifices to rescue the angry lost boy she’d married. She deserves great credit for rehumanizing her husband and so improving the safety of those around them. But it seems like a lot to ask of female partners of violent men to take on, in addition to all else they do, the daunting job of acting as society’s tacit rescue squad. It’s surely better to solve the problem at its many roots—with generous support for troubled families, school outreach programs, drug recovery centers, reduced mass incarceration, help with the skyrocketing costs of higher education, and enhanced understanding of the forces at play that Susan Faludi describes—all of which contribute to the male crisis itself.

This has not been President Trump’s approach. During his campaign, he promised to restore jobs in coal mines, on assembly lines, on oil rigs, and in steel mills. To this he added bad-boy appeals to sex and violence, as when he urged his supporters in Cedar Rapids in 2016 to “knock the crap” out of hecklers. Some interpreted this bravado as an unmistakable sign of insecurity; others saw it as a clear expression of male strength: one website for Trump supporters featured T-shirts with the slogan “Finally Someone with Balls!” No equivalent shirts emerged for Bernie Sanders.

But some of Trump’s decisions in office are highly likely to hurt the very men who support him. His proposed federal budget—although not the one that Congress eventually passed—slashed public money for regional development programs such as the Appalachian Regional Commission, which has a strong record of supporting job retraining for unemployed coal miners. When Trump claims he can restore blue-collar jobs to American men, he persistently ignores the technological developments that have brought us the automated oil rig, the clerk-free store, the self-driving truck. Estimating the “automatability” of each of 702 different occupations, Oxford scholars found that for derrick operators it was 80 percent, for chemical plant and system operators, 85 percent, for petroleum technicians, 91 percent. Across the nation, jobs that have in the past mostly gone to men are now going to robots. Trump’s first choice as secretary of labor, Carl’s Jr. CEO Andrew Puzder, praised robots because they “never take a vacation, they never show up late, there’s never a slip-and-fall, or an age, sex, or race discrimination case.” Puzder’s “perfect” robot may be great for company stockholders, but it is ruinous for many male workers.

Never before has higher education in all its forms—BAs, associate degrees, computer-coding programs, job-retraining—mattered more for all Americans. And never before have American men earned a declining proportion of BAs, while BAs lead to better wages—especially for men. Yet in 2018, Trump proposed cutting over $200 billion from higher education over the next decade, mainly to reduce help to students struggling to pay its rising costs. Trump’s proposed cuts were large enough, according to a Center for American Progress report, to “pay twice over for a decade” of estate tax cuts for the rich. While Trump strongly appeals to Republican Fox News–watching men such as Mike Schaff, he is steering federal dollars away from the education such men will need for the jobs they badly want.

Meanwhile Trump is also doing nothing to help redirect wayward men from what is now the main source of domestic terrorism. When he revised the US government’s protocol for combatting violent extremism, Kimmel notes, he funded only programs addressing “radical Islamic fundamentalism” and canceled funding for those fighting white nationalism—including Life After Hate—even though, over the last decade, only 26 percent of politically motivated murders in the US have been committed by Islamic extremists and 71 percent by right-wing extremists.

As I was writing this piece, and thinking about the discontents of male identity, the photographer Richard Misrach happened to send me an extraordinary set of photographs he had shot over the last few years for a new project.6 The images were of graffiti scrawled on surfaces of cracked plaster in abandoned homes, long-forgotten weathered sheds, or on rocky outcroppings in the windswept desert sands of Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, California, and Nevada. “Wherever I went,” Misrach said, “I saw penises.”

One penis appeared on a golden desert boulder, outlined by a large heart and initials. Another appeared alone on a wall, forlornly ejaculating a tear-shaped homunculus. One aimed upward on the trunk of a tree as if trying to climb it. One was marked USAF for the United States Air Force. Yet another embodied the image of a skinhead man. In one startling case, the male member was carefully suited, as though striding off to the office.

There were no images of women. Drawn in abandoned places where few beyond a wandering photographer would look, Misrach’s anonymous scribbles seemed to express the idea of an organ isolated, castrated, expressing a story all its own. It was as if masculinity had lost its way. In some cases, detached from a human body, it had attached itself to something else. One penis was accompanied by a swastika, another by a “White Power” slogan, a third by a Confederate flag.

This Issue

October 11, 2018

‘I Can’t Believe I’m in Saudi Arabia’

The Red Baron

-

1

Another book out this year that covers much of this territory is Andrew L. Yarrow’s Man Out: Men on the Sidelines of American Life (Brookings Institution, 2018). ↩

-

2

David Autor and Melanie Wasserman, “Wayward Sons: The Emerging Gender Gap in Education and Labor Markets,” Third Way, 2013. ↩

-

3

Reviewed in these pages by Andrew Hacker, October 21, 1999. ↩

-

4

For the historical precedents of extremism, see Linda Gordon, The Second Coming of the KKK: The Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition (Liveright, 2017). ↩

-

5

For a closer description of the ripped-up childhoods of American neo-Nazis, see Elinor Langer, A Hundred Little Hitlers: The Death of a Black Man, the Trial of a White Racist, and the Rise of the Neo-Nazi Movement in America (Metropolitan, 2003). ↩

-

6

Richard Misrach, “The Writing on the Wall,” shown at Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, July 31–August 15, 2017. ↩