Last year I got a call from Abbess Yin, an old friend who runs a Daoist nunnery near Nanjing. I’ve always known her as supernaturally placid and oblique, but this time she was nervous and direct: a group of Germans were coming to spend a week learning about Daoist life; could I travel down from Beijing to help? To translate, I asked? No, she said impatiently, to mediate—to avoid a disaster. These foreigners, she explained, had spent years learning qigong (a neologism that refers to Chinese forms of meditation and exercise practices broadly similar to tai chi). But they knew nothing about Daoism. This perplexed her—how could they know one without the other? She foresaw innumerable misunderstandings.

I imagined days spent translating words like “energetics” into Chinese and dredged up a host of reasons why I was busy. Abbess Yin let the line stay silent for a few strategic seconds, forcing me to do what I knew I must: wimp out and accept. I steeled myself for a lost week.

Abbess Yin was right: it was a week of misunderstandings, but it was also illuminating. At heart, each side was worried about being used by the other. Once this mistrust was overcome, something meaningful and even beautiful took place.

Many of the concerns were small but symptomatic. The Germans objected to having their pictures taken at every turn, thinking it was part of a money-making ploy to sell lessons in China, a not unreasonable assumption. They also didn’t want to wear Daoist robes on a visit to a nearby town, feeling they were props in a circus act. And they weren’t keen on lectures about the interminable number of Daoist deities; what did this have to do with learning new forms of Daoist exercises and meditation?

As for Abbess Yin and her nuns, they were perplexed too: these foreigners knew so little about the Daoist religion other than the Daodejing, the classic text of aphorisms ascribed to Laozi.1 The nuns were a bit upset that their techniques of self-cultivation—meant to encourage a virtuous life and achieve enlightenment—had become mere skills for the foreigners to use in their professions, which ranged from massage and conflict resolution to personal coaching. It struck me as analogous to nonbelievers using a church as a setting for a wedding.

After a bit of shuttle diplomacy, we reached an accord. The nuns explained that the photos were meant to show local officials how adept they were at spreading Chinese culture—a big priority under Xi Jinping. Doing this would give them a bit more leeway in dealing with the omnipresent Communist Party. The Germans understood and agreed to being photographed, as long as the photos wouldn’t be made public without their consent. As for the robes, the Germans also assented once they understood that the nuns are often seen as oddballs in the community. Here was a chance to show that even foreigners respected their learning.

As for the nuns, they reduced the lessons on the history of Daoism and increased practical lessons in Tai Chi, meditation, and other physical practices. Slowly, the two sides began to understand each other better. After a few days, the foreigners began attending the nuns’ morning prayers, and the nuns were offering extra lessons.

On the last day, the new friendship was crowned by something everyone wanted: a group photo. For the nuns, it would adorn the wall of their office as proof of the power of the Dao to attract even cranky foreigners, while the Germans could display the blue-robed nuns back home to prove that they had gone all the way to China to learn authentic qigong, something that not every masseuse in Munich can claim. The encounter left Abbess Yin elated and thoughtful. Before I left for the high-speed rail station, she pulled me aside. “Maybe this kind of course can appeal to Chinese people too,” she said. “Many Chinese people also don’t know much about Daoism.”

On my way back to Beijing I thought about this and wondered why Daoism was so hard for people to understand. When friends—foreigners or Chinese—hear that I regularly visit Daoist temples, they inevitably bombard me with questions: What is Daoism? Is it a philosophy? A religion? Isn’t it about meditating on a mountaintop? If so, then why the brightly colored temples or the stalls hawking incense? Why is it all so different from Laozi and Zhuangzi?

Then, a few weeks later—call it coincidence, but I prefer to think of it as divine intervention—I got the manuscript of David A. Palmer and Elijah Siegler’s Dream Trippers. Soon, many things that had troubled me about Daoism and religious exchanges began to make sense.

Advertisement

Religions have spread around the world in many ways; few have arrived as a feat of literary imagination. But that is exactly how Daoism came to the West, helping to make it one of the most misunderstood faiths. It wasn’t transmitted by Chinese missionaries or practitioners but by Western scholars whose interlocutors weren’t even Daoists; on the contrary, they were people hostile to the religion.

To understand how this happened, we need to step back two thousand years to the beginnings of Daoism. Back then, Chinese religious practices were not part of an organized religion. Instead, Chinese followed a shared system of rituals and beliefs: shrines to ancestors, deified geographic features and historical personalities, belief in divine retribution for evil, and a pantheon of gods who represented different aspects of these beliefs. This is still how much of religion is practiced today in China, often under the name “folk belief” (minjian xinyang).

Around the second century CE, some Chinese began to structure their beliefs into a religion. Basing it on the Han dynasty’s rituals and bureaucracy, the new faith was centered around the text of the Daodejing, and deified the text’s mythic author, Laozi. Priesthood was often passed in lineages from father to son.

Buddhism’s arrival in China in the first century CE had revolutionized Chinese religious life. Here was a faith with an organized clergy of missionary monks who had a clearly defined corpus of holy scriptures and novel practices. Over the centuries, Daoism adapted to this. Some explicitly imitated Buddhist practices, such as vegetarianism, celibacy, and constructing monasteries. This became known as the school of Complete Perfection (Quanzhen), while the older version of Daoism, which allowed priests to marry and live in communities, is today known as Orthodox Unity (Zhengyi).

Throughout it all, Daoism sold itself as an indigenous counterpoint to Buddhism. During some dynasties this worked in Daoism’s favor, and it was sponsored by the state. The first ruler of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), for example, was inspired to fight against China’s Mongolian conquerors by calling upon a Daoist deity known as Zhenwu, the Perfected Warrior.

But opinion turned against Daoism in 1644, when the Ming fell to another nomadic people, the Manchus. Not only was Daoism seen as too Chinese, but the Manchus practiced Tibetan Buddhism—hence the huge number of Tibetan-style temples in and around Beijing from that era. Daoism wasn’t banned but withered among urban intellectual circles. Instead, it flourished mainly in the countryside, where its ideas influenced folk beliefs to the point that the two became almost indistinguishable.

It was this state of affairs that Western scholars encountered when they arrived in China. Not only was Daoism weak, but the foreigners’ interlocutors were the Confucian elite who ran China. These educated officials disdained most religions, but were especially hostile to out-of-favor Daoism. They conceded that the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi were beautiful texts, but said the religion was debased superstition.

Thus began what surely must count as one of the most inaccurate and misleading notions in the history of intercultural religious understanding: that there is a “Daoist religion” (daojiao, in Chinese) and a “Daoist philosophy” (daojia) that have little to do with each other. The philosophy, it was held, was deep and profound. But the religion was superstitious nonsense, practiced by fortune-telling charlatans who might have some skills in martial arts or geomancy but who possessed no philosophical knowledge. Hence the West came to believe that China’s only indigenous religion was a corrupted version of a once-grand system of belief. Not coincidentally, this was how the West also saw China: as a fallen empire.

This way of understanding Daoism is wrong. Of course, one can appreciate the Daodejing without being a Daoist, just as one can admire the Sermon on the Mount without being a Christian. But to say that Christianity has nothing to do with Jesus’s ideas is absurd, just as it is ridiculous to say that Daoism is a burlesque version of a profound philosophy. This is obvious if one goes to a Daoist temple and listens to, say, the morning prayers, or zaoke. They might sound like rapid and meaningless chanting to someone unfamiliar with the language, but in fact they are very clear restatements of the ideas of Laozi that any Chinese person with a high school education can understand.

More than that, Daoism is the repository and sometimes the inspiration for many cultural practices in China, including notions that underpin landscape painting and concepts such as yin-yang and the five elements, which underlie Chinese medicine. Buddhist missionaries were so effective that even today the word for the Buddha, fo, is synonymous with the word for a god or spirit. But it is Daoism that gives a cosmology to all the folk religious practices that make up the majority of ethnic Chinese people’s religious activity, from deifying sacred mountains and historical figures to the geomantic principles that determine how communities and graves are laid out. And it is Daoist ideas of meditative internal cultivation that inspired one of China’s most famous cultural exports, the Buddhist school called Chan, better known abroad through its Japanese name, Zen.

Advertisement

Probably the person most responsible for our misunderstanding of Daoism is James Legge, the Scottish missionary and translator who was a leading scholar of Chinese religion for about twenty years, starting in 1870. Legge was an admirable figure, pioneering the translation of many Chinese classics out of genuine respect and admiration for Chinese culture. But he venerated Confucius (whom he held to be almost on par with Jesus); toward Daoism he followed the Confucian prejudice of esteeming the ancient texts but denigrating the religion, setting up the misunderstanding that is still widespread today.

By the time the World’s Parliament of Religions was held in Chicago in 1893, Daoism was probably the least understood of the faiths present. Representatives of many world religions spoke on an equal footing with their hosts, but Daoism was represented by an anonymous essay that called on outsiders to “restore our religion.” This didn’t stop Westerners from fetishizing the Daodejing. As Palmer and Siegler note, this is due to the text’s brevity, its having few Chinese names to confuse readers, and its openness to multiple interpretations. By 1950, ten translations of the Daodejing were in print, with one declaring that “Taoist religion is an abuse of Taoist philosophy.”

Thus today we are presented with a strange phenomenon: bookstores around the world are stocked with endless translations of the Daodejing—widely considered to be the most-translated book after the Bible—but as Palmer and Siegler put it, “the contours of Daoist practice, both current and historical, are usually ignored, derided, and/or misunderstood.”

This downplaying of the Daoist religion is reflected in a new translation of the Daodejing by John Minford, one of the most famous translators of Chinese into English. In his Tao Te Ching: The Essential Translation of the Ancient Chinese Book of the Way, Minford offers a lucid translation of the old text, as well as of some Chinese commentaries.2 Minford writes that his version is not aimed at scholars, but is meant to be a “guide to everyday living,” which is fair enough, but he leaves out much of what the commentators have to say about using the text as a tool for traditional meditative practices. In a section on Daoism today, he mentions the Beatles, Ursula K. Le Guin, and The Tao of Pooh, but completely omits that Daoism is also a vibrant, living religion with temples, priests, and nuns, who worship Laozi as a god. Instead, the text is presented as “the original mindfulness book.”

The story of Daoism’s travails is ably recounted by Palmer and Siegler, but their goal is more ambitious. Through a series of entertaining encounters centered on a holy Daoist mountain, they also raise fundamental questions about how post-religious people strive, often unhappily, for spiritual fulfillment.

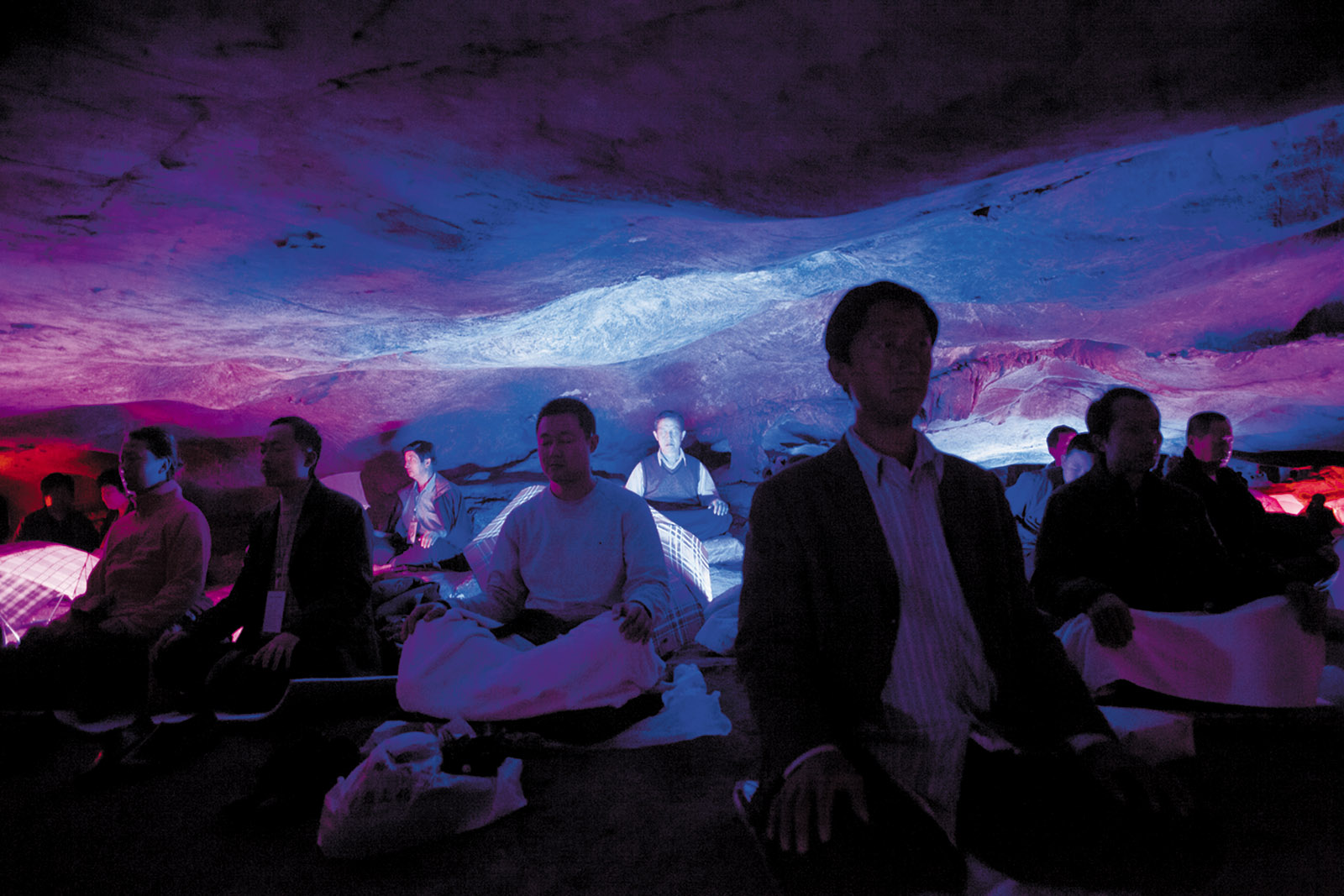

Their story has two heroes, or antiheroes. One is Michael Winn, an entrepreneur who leads tours to China that he calls “Dream Trips.” These include regular tourist stops, such as the Great Wall and the terracotta soldiers, but the high point is a visit to Mt. Hua, a Daoist mountain near the city of Xi’an. This is one of Daoism’s five holiest sites, with near-vertical ascents that in the past were only accessible by stairs cut into the rock face and chains slung down as handrails. Winn, though, picked it more or less serendipitously because he felt the “energy” of the mountain. He made friends with local Daoists and brought his Trippers there to meditate in its caves and feel its power.

Like the Germans I escorted to the abbess’s temple, few of Winn’s Dream Trippers know much about Daoism. Many have been through the wringer of spiritual practices, having tried, according to Palmer and Siegler, “Transcendental Meditation, the Gnostic church, Kundalini yoga, macrobiotics, LSD use, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (also known as ISKCON or Hare Krishna), Healthy, Happy, Holy Organization (also known as 3HO and now sometimes called Sikh Dharma), and American shamans,” not to mention Tai Chi, shamanic peyote cults, angel channeling, and Tibetan Buddhism. Like most spiritual seekers, they’ve read the Daodejing but have no real interest in “religious Daoism”—in other words in Daoism’s history, gods, or beliefs. In true Orientalist fashion, they see local practices as backdrops for their personal journeys.

The Dream Trippers want an imaginary Daoism, seeing it as feminine, ecological, and subversive. It has techniques they can use, but little else. It’s what they experience that matters, or as Palmer and Siegler put it, “subjective experience in one’s own body is the only source of authenticity.” For that, bits of China are useful, especially holy sites, which they believe contain centers of energy that they can tap into—spiritual gas stations that could be located anywhere.

Daoism, the authors speculate, is perfectly suited for this cultural smorgasbord because it offers a complete system of meditation, philosophy, and physical practices for health, healing, martial arts, enhancing the meaning and pleasure of sex, and placing the body in a cosmos. Crucially, these ideas and skills can be learned in discrete packages; a person can take one part and leave the rest. Many other religions, by contrast, have unappealing core ideas or practices; non-Tantric Buddhism eschews sex, for example, while Tantric Buddhism and Hinduism place an emphasis on guru devotion and ritual that is antithetical to many of these individualists.

It’s easy to see the Dream Trippers as simply wanting to reenchant their lives—to bring back the spiritual or divine that modernity and secularization have driven out of daily life. But Palmer and Siegler say they represent something else: “ultramodernity.” Modernity put religion in a compartment and built a society around the assumption that objective and universal reason existed. Ultramodernity questions that premise, seeing everything as subjective. Spiritualism is taken out of the box of organized religion and given to the individual, who can assert it as justification for behavior in any sphere of life, not just the religious sphere.

The Dream Trippers’ foil is Louis Komjathy, a scholar who diligently seeks authentic Daoism. Komjathy is a well-known scholar of Daoism at the University of San Diego. He recently published, for example, an outstanding annotated translation of a classic Daoist book of contemplation, Taming the Wild Horse.3 Like Winn, he is a seeker but wants to find meaning in the religion’s lineages and monastic-based practices.

But as Palmer and Siegler’s book unfolds we get a more nuanced picture of Winn and Komjathy. We see this through the eyes of the Daoist monks themselves, a brilliant decision by the authors because it makes the Daoists into actors rather than extras. Many of them disdain the Dream Trippers’ ignorance. Like Abbess Yin, they think the foreigners are missing the point—how can one learn the techniques without the morality? But they also welcome them as proof of China’s broader cultural, economic, and political rise. Some even enjoy the Trippers, seeing in them a naive, fun way of looking at their own religion. They can’t communicate but do meditate and sometimes even dance together.

And while many of the monks respect Komjathy, they also see him as too rigid. Indeed, we begin to see that Komjathy is almost as Orientalist as the Trippers. He seeks a pure, strict form of Daoism that rarely exists in China, certainly not in the backbiting, commercialized world of touristified monasteries such as Mt. Hua. In fact, his own master is so disgusted by the degradation of the holy site that he has quit the mountain and his monastic order to live in the city and teach people privately. On the basis of his master’s initiation, Komjathy calls himself a Quanzhen Daoist, but Quanzhen is a celibate, monastic order, while he is married and lives a secular life as a university professor.

Thus we come to the predicament of the book’s subtitle. Both Michael Winn’s Dream Trippers and Komjathy have decided for themselves what spiritual practice they want, making it an individual choice outside an organized religious structure. But this makes them wonder if their choices are valid, and crave authenticity as a way to justify them. So while the Trippers might eschew traditional Daoist practices, they still need the trip to Mt. Hua to give substance to their practice.

Komjathy, too, yearns for authenticity. He searches for masters who can initiate him into a lineage, even though, as Palmer and Siegler point out, Daoist lineages have been largely destroyed by the upheavals of the twentieth century. There is no direct transmission of the ancient wisdom; instead it is a recreation of a lost past.

This is a wise, funny, and at times moving book. It helps us understand not only one of the most misunderstood of the world’s religions, but also our own fates as post-religious people. Many of us have cast ourselves adrift in the world, seeking our own spiritual salvation through cobbled-together ideas drawn from humanism and eclecticism. But we often wonder if we aren’t worse off than members of a traditional faith: unsure of what to do, we can’t focus on higher goals.

If popular understanding about Daoism in the West is often shaky, we are lucky to live in a time when academic understanding of Chinese thought has never been stronger.4

One of the most imaginative new books to come out of the West’s engagement with Daoism is James Miller’s China’s Green Religion. Miller argues persuasively that Daoism can be seen as a kind of counterculture to the dominant Confucianism of the past centuries. This, along with its tradition of engagement with nature—rather than dominance over it—can allow Daoism to serve as a support for a new kind of environmentalism. Instead of being based on the arguments of scientists, lawyers, and economists, respect for the environment can be based on Daoism’s teachings of living in harmony with the environment—a way to move “from a technical policy discourse to popular practice.”

The idea that Chinese traditional philosophy might have something valuable to add to world discourse shouldn’t be shocking, but Bryan Van Norden argues in Taking Back Philosophy that it is almost heretical in most US universities. This is a wonderfully lucid, purposefully polemical tract calling for non-Western philosophies to be introduced into university curricula.

A better verb might actually be “reintroduced,” for, as Van Norden shows, non-Western thinkers like Confucius were considered to be philosophers until the discipline narrowed its field of vision in the nineteenth century. Van Norden focuses on Chinese philosophy because he knows it best—he taught Chinese and comparative philosophy for twenty years at Vassar and currently is a visiting professor at Yale-NUS College in Singapore—but he says it applies to other non-Western philosophers as well.

Van Norden floated the idea of making philosophy more diverse in a 2016 New York Times column that he co-wrote with Jay L. Garfield.5 The two were pilloried for their effort. One criticism was that philosophy originated with Plato, so Chinese like Confucius couldn’t be philosophers. Another strange argument was that non-Western philosophers might be sages with some smart ideas but they didn’t argue their points rigorously enough.

As Van Norden points out, none of these critics is able to read the works they dismiss in the original language, and most admit to having barely engaged with them in translation. But their prejudices are not unusual; instead, they are common in universities across the United States. Most striking is that of the top fifty philosophy departments in the United States that grant a Ph.D., only six have a regular faculty member who teaches Chinese philosophy. By contrast, each of them has faculty who can lecture on the ancient Greek Parmenides, of whom history has left us only one work.

Why should we care? Van Norden says it’s not about political correctness. Instead, he shows how Chinese philosophers have much to offer the great philosophical debates. Hobbes, for example, argues that people act out of self-interest and that coercive power is necessary to compel humans to follow rules. China has philosophical schools with similar ideas: Legalism and its opponent, Confucianism. How Western philosophy departments can marginalize these Chinese thinkers is a mystery.

Perhaps if more Chinese philosophy were taught, then the ideas that underpin Daoism would be demystified. Instead of China being seen as a repository of Oriental wisdom, its ideas would be taken seriously as part of a dialogue that engages all people everywhere: one about how to live dignified lives with a higher meaning.

This Issue

November 8, 2018

MLK: What We Lost

The Concrete Jungle

‘Inventing New Ways to Be’

-

1

Dao is the same as Tao, as are Daoism and Taoism, the Daodejing and the Tao Te Ching, as well as Laozi and Lao Tzu or Lao-tze. They are simply different ways of Romanizing the same Chinese characters. I follow universal academic practice (including that of the authors of the books under review) of using the official pinyin system—thus Dao, Daoism, Daodejing, and Laozi. ↩

-

2

To be published by Viking in December. ↩

-

3

Taming the Wild Horse: An Annotated Translation and Study of the Daoist Horse Taming Pictures (Columbia University Press, 2017). ↩

-

4

For a summary of recent significant books, see my “China Gets Religion!” in these pages, December 22, 2011. ↩

-

5

“If Philosophy Won’t Diversify, Let’s Call It What It Really Is,” The New York Times, May 11, 2016. ↩