On a sweltering July night in 1899, five immigrant Sicilian produce vendors were seized by a furious mob in Tallulah, Louisiana, and publicly hanged. The night before, Dr. J. Ford Hodge, the coroner of surrounding Madison Parish, had shot a goat that had wandered into his garden. When the animal’s owner, fifty-four-year-old Pasquale Defatta, confronted him the next day over the loss of his goat, Hodge knocked him to the ground, pistol-whipped him, aimed the gun at Defatta’s head, and pulled the trigger, but it jammed. At that point, his brother Giuseppe, thirty-four, ran out of the family’s nearby store with a shotgun and fired at the doctor. Hodge sustained superficial wounds—birdshot pellets in the abdomen and thighs. Rumors soon erupted that the doctor had been murdered, and a mob came after the Defattas.

Pasquale and Giuseppe were lynched first, strung up in a slaughter yard on a winch used to skin cattle. Their brother Francesco, thirty, and their cousins Rosario Fiduccia, thirty-six, and Giovanni Cirami, twenty-four, were then dragged to a cottonwood tree on the village square. To the very end, even with a noose around his neck, Francesco believed that his American neighbors only meant to frighten him, to teach his family a lesson. “I live here six years. I know you all. You all my friends,” a witness recalled him saying. Then the rope was suddenly yanked.

No one was arrested for the lynchings. Three grand juries found that no indictment could be issued. It had been “too dark” that moonless night to identify anyone in the lynch mob, the local sheriff testified. The Tallulah telegraph operator had been put under armed guard to prevent him from tapping out news of the men’s seizure and calling for help. If he touched the wire key, he was told, “his brains would be blown out.”

In the epoch of political chicanery, behemoth industrial monopolies, and explosive demographic changes that Mark Twain dubbed “the Gilded Age”—roughly between the 1870s and 1900—the specters of immigration and race led to waves of extrajudicial killings, involving or covered up by law enforcement authorities and implicitly endorsed by the nation’s highest officials. Most of the victims were African-American. But there were at least fifty lynchings of Italians, most of them between 1890 and 1924, when the Johnson-Reed Act (also known as the National Origins Act) placed draconian limits on immigration to the United States from the Mediterranean Basin.

Ostensibly, Sicilians were white Europeans. But “they were a puzzle to white people” in rural Madison Parish, 230 miles north of New Orleans, wrote the Harper’s Weekly reporter Norman Walker, who was assigned to cover the lynchings. The Sicilian fruit vendors

were difficult to classify, and this was more difficult because they dealt mainly with the negroes, and associated with them nearly on terms of equality. They could, therefore, hardly be classed as “white men.”… Just how to treat them was a difficult problem.

On July 20, 1899, in the cattle pen and on the cottonwood gallows of Tallulah, that problem had “finally been settled,” Walker concluded. “They are to get the justice awarded a negro…lynching, not a trial.”

The incident had been blanketed in silence for more than a century when Enrico Deaglio overheard a chance reference to it while visiting the family of his Italian-American wife, the literary translator Cecilia Brunazzi, in Tallulah. “Let’s hope he doesn’t find out about the five lynched Italians,” a neighbor muttered to his sister-in-law.

Over the next several years, Deaglio—one of Italy’s best-known journalists and the author of twenty-two books—pursued a stubborn investigation into what had transpired on that distant summer night. The result is Storia vera e terribile tra Sicilia e America (A True and Terrible Affair Between Sicily and America), which was a best seller for more than a year in Italy and won three prestigious national awards. One critic called it “an Italian In Cold Blood.” Like Truman Capote’s famous inquiry into a Kansas murder spree in 1959, Storia vera is rich in social and psychological insight, with the vividly drawn characters and dramatic intensity of a novel.

Deaglio has honed his detective skills in four decades as a leading investigative reporter for Italian newspapers, magazines, and broadcasting. His books have examined the rise of Silvio Berlusconi, Italy’s Trump-like prime minister for nine years; the assassination of the anti-Mafia judge Paolo Borsellino; and the secret heroics of Giorgio Perlasca, an Italian businessman who posed as a Spanish diplomat in wartime Budapest and saved more than five thousand Hungarian Jews from deportation to Nazi death camps.

Deaglio managed to retrace the chronology of the lynchings in Tallulah in minute detail and to place them firmly in the larger setting of Louisiana’s lethal history. He unravels the curious saga of Dr. Hodge, who suddenly and mysteriously left his post as coroner a few months after the lynchings and was never heard from again. Not the least of Deaglio’s accomplishments is his discovery of solid evidence that many participants in the lynch mob had personal motives for ridding Madison Parish of its troublesome Sicilians. Some of those motives were clearly business-related. At least one appears to have involved sexual jealousy.

Advertisement

The incident at Tallulah was not an isolated event. Eight years earlier in New Orleans, eleven Italians had been killed in the single worst mass lynching in US history. Nearly 130 years passed before the atrocity was acknowledged by New Orleans authorities, in the form of an official apology to the victims’ descendants this April by Mayor LaToya Cantrell.

On October 15, 1890, New Orleans police chief David Hennessy was ambushed and shot a few blocks from his office. Conscious for hours afterward, he spoke with many close friends who rushed to the hospital, but was unable to identify his assailants. Only one visitor, police captain William O’Connor, saw him privately. O’Connor claimed that when he asked who the shooters were, Hennessy whispered, “dagos.” On that unverifiable charge, up to 250 Italian immigrants were rounded up after Hennessy died the next day.

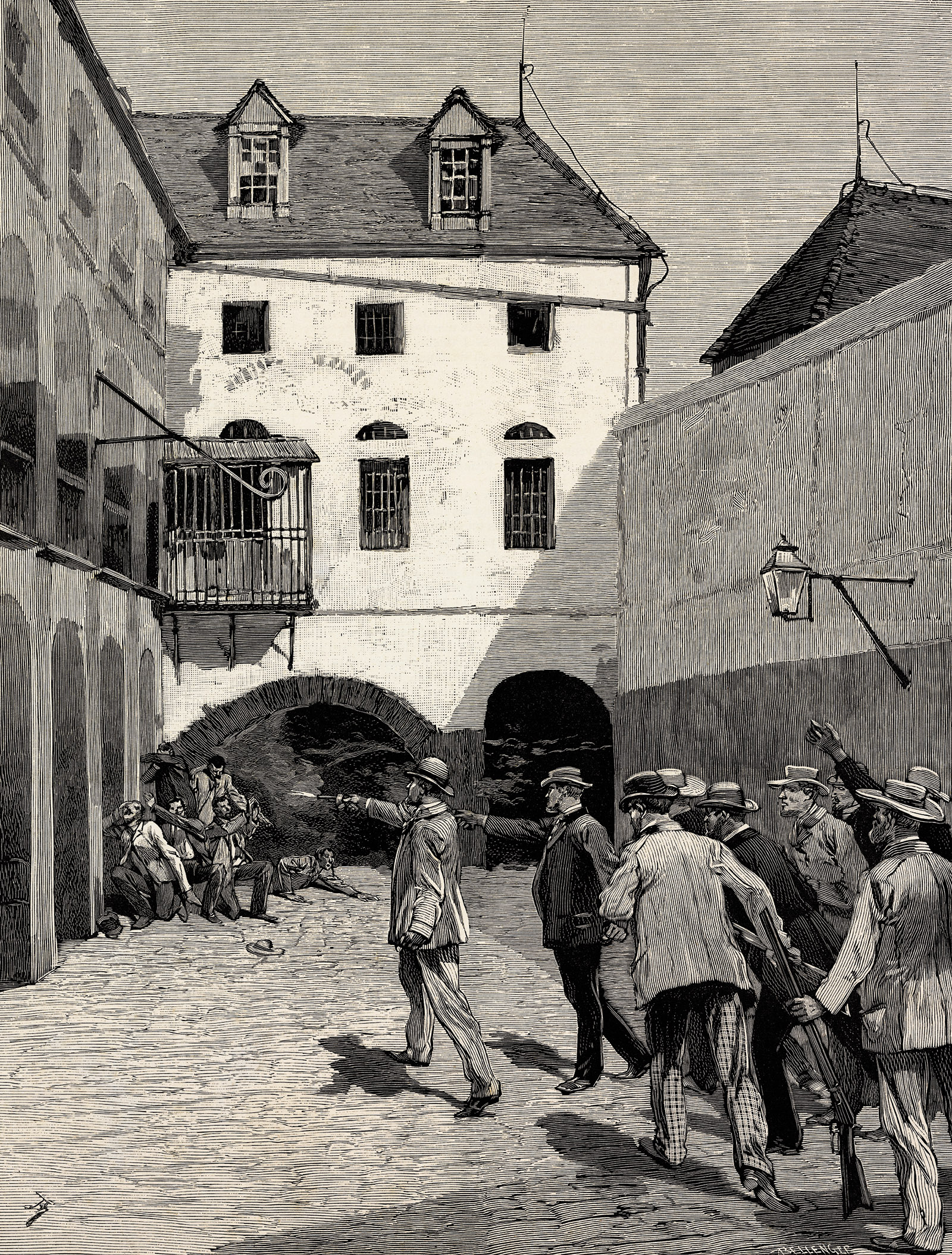

Eventually, nineteen men were indicted on evidence so flimsy that six of the first nine defendants to face a jury were acquitted and the three others were ordered freed in a mistrial on March 13, 1891. The remaining ten were never tried. All nineteen were still in jail on March 14 when an enraged crowd numbering thousands broke into the building chanting: “We want the dagos!” It was led by some of the most prominent citizens of New Orleans, including a newspaper editor, a future mayor, and a future governor of Louisiana. Two of the Italians were dragged into the street and hanged. Nine more were shot or clubbed to death inside the jail. They included fruit vendors like the Defattas, two dock workers, a tinsmith, a cobbler, a rice plantation laborer, and a local ward politician.

Their killings were justified in the name of combating a new menace in the city’s corrosive underworld: “the mafia.” Yet in 1890 its existence and reach were more fantasy than fact. The district attorney conceded that no evidence tied the nineteen defendants to the Hennessy shooting or to organized crime. But most political figures and media commentators tended to see it the crowd’s way.

“These sneaking and cowardly Sicilians, the descendants of bandits and assassins, who have transported to this country the lawless passions, the cut-throat practices, and the oath-bound societies of their native country, are to us a pest without mitigation,” The New York Times editorialized. “Lynch law was the only course open to the people of New Orleans.”

The Times’s sentiments echoed prevailing opinion in Italy itself, where Sicilians were widely regarded as a “cursed race,” irresistibly prone to crime and depravity due to origins that were not Teutonic European. In 1860 Carlo Farini, the chief administrator of Sicily for Prime Minister Camillo Cavour, wrote that the South “is not Italy! This is Africa: compared to these peasants the Bedouins are the pinnacle of civilization.”

By the 1890s, such views were enshrined in what then passed for advanced criminology. Their chief exponent was a northern Italian physician, Cesare Lombroso, whose 1876 book L’uomo delinquente (later published in English as Criminal Man) argued that anatomical characteristics, especially skull dimensions, were hallmarks of inherited sociopathic behavior. His studies, he asserted, demonstrated that “African and Oriental elements” in the demographic profiles of Calabria, Sicily, and Sardinia excited murderous instincts. Southern Italians, in other words, were born criminals.

Lombroso’s racial theories were highly influential in the United States. “Monday we dined at the Camerons,” Theodore Roosevelt wrote his sister on March 21, 1891. “Various dago diplomats were present, all much wrought up by the lynching of the Italians [one week earlier] in New Orleans. Personally I think it rather a good thing, and said so.” In 1894 Roosevelt was appointed New York City’s police commissioner. Two years after the Tallulah incident he became president of the United States.

Yet despite such prejudices, Deaglio presents evidence of close collusion between the Italian government and US business figures in the same years to encourage what he describes as a “biblical migration” from the Italian South to the American South. In the two decades bracketing the turn of the century, 90 percent of an estimated 100,000 Italian immigrants who disembarked in New Orleans were Sicilian.

What propelled the migration was surplus labor on one side of the Atlantic and a labor shortage on the other. The five Tallulah victims were among two generations of Sicilian peasants dispossessed by Giuseppe Garibaldi’s overthrow of the reactionary Bourbon monarchy and its immense aristocratic estates in the 1860s. The consolidation of Italy as an increasingly industrialized nation left millions of unskilled laborers in Sicily with no land to work and no livelihoods. Northern Italians consumed by fears of racial contamination were openly relieved to see them leave.

Advertisement

If the newcomers were viewed as an unmitigated peril by the Times, their arrival was welcomed in Louisiana and Mississippi by cotton and sugar growers anxious to replace freed slaves, who by the 1880s were steadily migrating north and no longer provided a captive, unpaid workforce for sprawling plantations. Both states began to actively recruit southern Italian laborers, led by the Louisiana Sugar Planters’ Association, which represented five hundred growers. They lobbied successfully for legislation to facilitate Italian immigration and signed direct accords with Italian diplomatic officials in Washington to boost the numbers of migrants “under the protection of the King of Italy.” The association’s agents scoured Sicily in search of healthy young men, promising free passage to the United States and a ticket back home if desired. The only requirement was that they remain with the contracting plantation for a minimum of six months. Families were also welcome, but they too would be obliged to work. The climate, the agents said, was ideal, and the salary was $20 per month, a fortune by Sicilian standards.

But instead of a worker’s paradise in Louisiana, most Italian contract workers experienced long, back-breaking days of hard labor in searingly hot fields, where they were surrounded by armed horsemen who oversaw the work and prevented any escape. State vagrancy laws had been expanded, also under pressure from the growers, making the farm laborers liable to arrest if they left the plantation grounds. When it rained, as it often does in the relentlessly humid Mississippi River lowlands, there was no work and no pay. As for the $20 salary, much of it was in the form of tokens convertible only at the plantations’ company stores and inscribed “valid for a portion of meat,” or “valid for a portion of cornmeal.”

This is almost certainly the bleak world that swallowed the Defattas in America, although Deaglio was unable to find the details of their lives in the records that survive of plantation labor. The brothers vanished from history soon after their disembarkation in New Orleans in 1890. When they resurfaced at decade’s end, selling fruits and vegetables in Madison Parish, the Italian community of New Orleans had swollen to 20,000—10 percent of the city’s population and almost entirely Sicilian. Across the state, their relations with the local population were volatile, inflamed by the “scientific” confirmation of southern Italian depravity and endless tales of organized crime—some genuine, most invented and hugely inflated.

Every man in the lynch mob at Tallulah “knew all about the mafia and all about the Hennessy murder,” the New Orleans Daily States commented. “They looked on these degenerates as monsters, capable of any infamy and they determined to destroy them root and branch.”

But white paranoia was being driven by something even more terrifying. With the influx of Italian laborers, the wall between the races in the Deep South was beginning to crumble. The 1890s saw the rapid growth of a union movement in New Orleans and intense cooperation between African-Americans and working-class whites—notably Sicilian dockworkers. One result was an unprecedented insistence, popularly known as the “50-50 rule,” that any work crew hired to unload a ship must be divided equally between black and Sicilian stevedores. They worked alongside one another in mixed teams for the same pay. The explicit purpose was to prevent employers from pitting laborers against one another along racial lines.

The 50-50 rule was formalized in 1901 by the establishment of the Dock and Cotton Council, which amalgamated black and white unions in a single organization under racially mixed leadership. Within two years, the council had absorbed eight separate black and white unions, with some 10,000 members.

It would be impossible to exaggerate the impact of such news in a place as riven by racial anxieties as Madison Parish. “It is the blackest district in the United States,” Norman Walker observed in Harper’s Weekly:

In a population of 10,000 there are only 160 white families. There are 20 negroes to one white, and in some sections they stand 100 to one. Yet the entire power is in the hands of the whites. They own all the land and other property. They alone vote: they alone sit on juries. They elect all the officers and administer all the affairs of the parish.

The Defatta brothers, their cousins, and fellow merchant Giuseppe Defina, a relative by marriage and the only other Italian adult in Tallulah, profoundly threatened that monolithic power structure. They were not only something other than “white,” but their customers were mainly African-Americans, by far the area’s largest market. The Sicilians sold produce that was cheaper and of higher quality than their competitors’. Moreover, they sold on credit rather than immediate payment in cash.

The fears stoked by the establishment of interracial unions in New Orleans and augmented by local prejudices ballooned with gossip that members of the Defatta and Defina families were applying for naturalization or had become US citizens. “There was a plot” in Tallulah in the summer of 1899, a white witness told Enrico Cavalli, editor of the New Orleans–based newspaper l’Italo Americano, who was sent to investigate the incident by the Italian government. The plot was not “among the Italians to do harm to the doctor, but among the shopkeepers of the village and others, from a spirit of rivalry and trade, and from a desire to prevent the Italians from voting.”

Deaglio notes that Giuseppe Defina had become one of the area’s most successful merchants. Although his general store was five miles away at Milliken’s Bend and he’d had no part in the encounter between Pasquale Defatta and Dr. Hodge, a posse left Tallulah intending to lynch him as well. He and his teenage son Salvatore barely escaped, rowing across the river in a small boat to the relative safety of Vicksburg, Mississippi.

All of Defina’s possessions were destroyed or confiscated in the following days. They included “a well-furnished house, which was full of all kinds of merchandise, household furniture, three horses, four carts, and eleven acres of land planted with indian corn and cabbages,” he testified in a court deposition. He presented the court with a ledger listing $2,000 in unpaid debts from customers.

The possessions of the Defattas also ended up in the hands of the lynchers. After a lengthy round of negotiations between Washington and Rome over the killings, an indemnity of $4,000 was paid by the US government to the families of Giuseppe Defatta and Giovanni Cirami—but nothing to the heirs of the other three victims or to Defina. The reasoning, strangely, was that the first two men were indisputably Italian citizens, protected by a treaty between Italy and the United States. Defina, Rosario Fiduccia, and Pasquale and Francesco Defatta, however, had applied for naturalization and were therefore excluded from the treaty’s protection. In short, lynching was treated as a crime only if the dead were foreign aliens.

Storia vera e terribile tra Sicilia e America is an eloquent indictment of the violent racism and xenophobia that haunted Italy and America alike at the turn of the twentieth century and still haunt both countries today. Contemporary examples include skinhead thugs braying abuse at African soccer players in the stadiums of Rome and Verona, and the violent August 2017 rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, organized by a coalition of more than a dozen American extremist groups. It culminated in the death of Heather Heyer, a thirty-two-year-old counter-protester, when a self-identified white supremacist drove his car into a crowd opposing the rally, injuring forty. Three days later, President Donald Trump conceded that there were “some very bad people” among the rally participants. “But you also had people that were very fine people, on both sides,” he added. In his assertion of moral parity, the president overlooked the fact that one of those two sides featured armed militiamen carrying automatic weapons and neo-Nazis chanting racist and anti-Semitic slogans. The echo of Tallulah is deafening.

Although Deaglio has signed an agreement with Rome-based Palomar Television and Film to make a movie based on the events in Storia vera, he has been unable to find an agent or publisher for an English-language translation. In the United States, the lynchings are all but forgotten.