By the spring of 1952, the “iron curtain” that Winston Churchill had described as descending on the eastern half of Europe—“from Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic”—already felt impenetrable, even permanent. In that year, Czech courts condemned to death Rudolf Slansky, the secretary-general of the Czech Communist Party, for alleged participation in a “Trotskyite-Titoist-Zionist” conspiracy. The East German Communist Party adopted a new economic policy, the “Planned Construction of Socialism.” Harry Truman warned the US Congress of the “terrible threat of aggression” from the Soviet Union; across the Atlantic, the brand-new NATO alliance was preparing to accept a rearmed West Germany.

But 1952 was also the moment when the concept of “the West”—the liberal democratic bloc, unified by economic ties and a military alliance, staunchly opposed to the Communist regimes—came the closest to collapse. In March 1952 Stalin made a final attempt to set West Germany on an alternative course. Unexpectedly, he made a peace offer to America, France, and Britain, the powers then occupying Germany along with the Soviet Union. He proposed to unify Germany—and to keep it neutral. He declared that this unified, nonallied Germany could be open to the “free activity of democratic parties.” A few days later, he suggested that a neutral Germany might also have free elections, and even its own army.

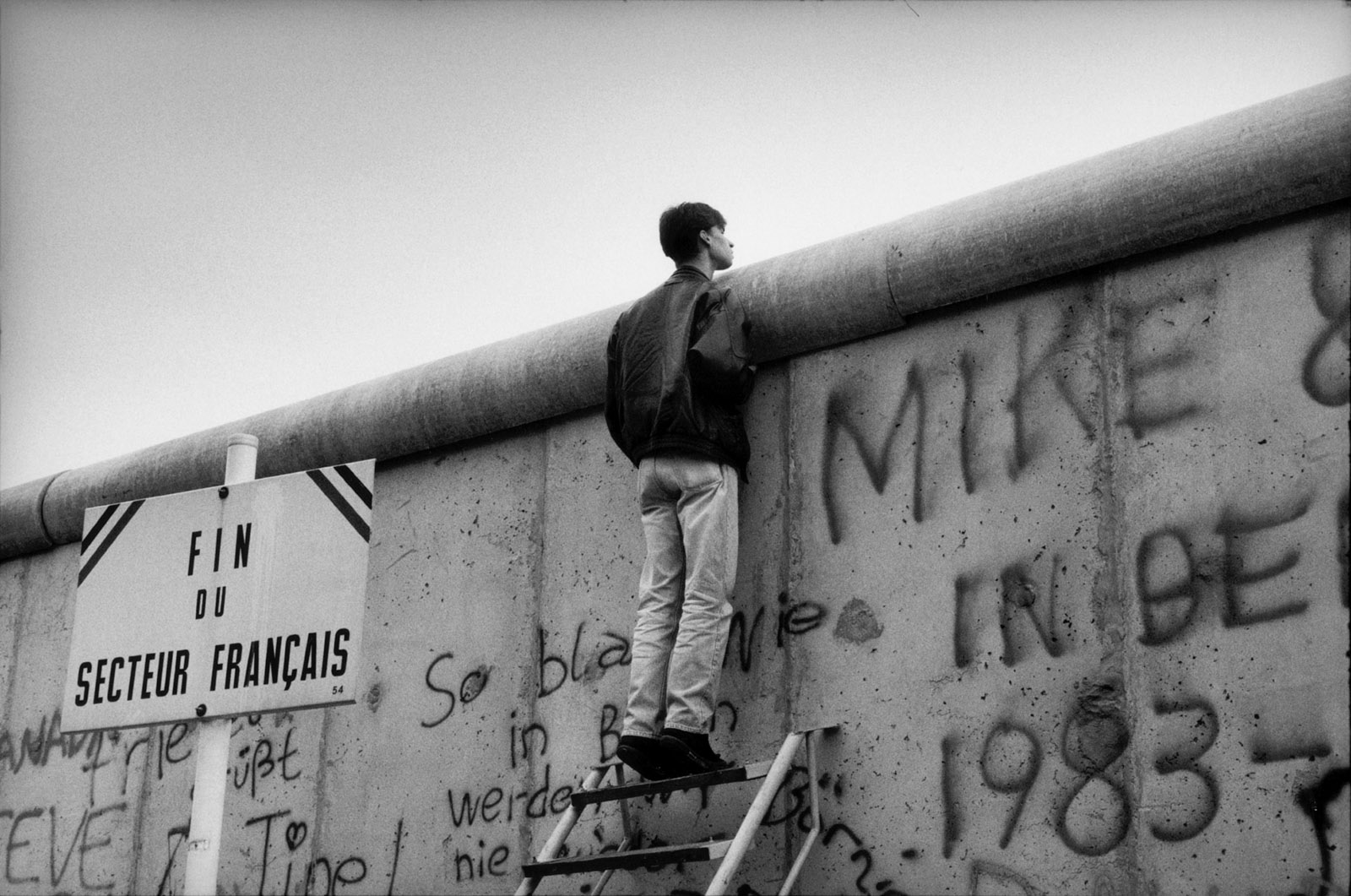

Kurt Schumacher, the leader of Germany’s Social Democrats, was tempted: he wanted to accept Stalin’s offer, as did many other Germans. But the man who was then West Germany’s chancellor, the Christian Democrat Konrad Adenauer, refused. He had good reasons: by 1952, it was already clear that “elections,” for Stalin, were a charade, a public relations exercise that could be manipulated or ignored. The West German economy was also several years into a boom of historic proportions, while the East German economy was falling behind. The deep contrast between the two halves of Germany—one prosperous and free, the other a poor dictatorship—was already visible. Thousands of Germans were moving across the border from east to west in larger numbers every year, an exodus that would end only in 1961, with the construction of the Berlin Wall.

The memory of Hitler, and of the recent war, haunted Adenauer and his compatriots too. The chancellor was afraid that West Germany’s new democracy might prove fragile, especially if it were put under direct pressure from the USSR. He thought that its survival required it to be bound tightly to the other nations of the West. And so Adenauer rejected the Soviet offer of unification. This decision, writes Ian Kershaw, was “highly controversial since it had a direct corollary: accepting that for the indefinite future there could be no expectation of East and West Germany uniting.” Adenauer not only accepted the division of his country, he also agreed to a permanent US military presence and to the deep integration of his country with the rest of Europe, especially Germany’s old enemy France.

In a sense, Kershaw’s The Global Age: Europe 1950–2017, an adept and useful synthesis of an extraordinarily complex era, is the story of what happened next. For roughly forty years, the nations of what we used to call Western Europe were all bound together by a similar decision: as a group, they chose democracy over dictatorship, integration over nationalism, social market economics over state socialism. In the name of fighting Soviet communism, and with the memory of World War II hanging over them, they accepted a set of liberal principles that some of them, most notably Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, had rejected only a decade earlier.

Although, as Kershaw writes, the political systems varied from country to country, they were “built everywhere on principles of law, human rights and personal freedom,” along with “restructured capitalist economies” that created the basis for growth as well as the welfare state. These systems were also remarkably stable, thanks not least to a “widespread desire for ‘normality,’ for peace and quiet, for settled conditions after the immense upheaval, enormous dislocation and huge suffering during the war and its immediate aftermath.” Indeed, “stability was paramount for most people. As the ice formed on the Cold War, every country in Western Europe set a premium on internal stability.”

Toward this end, together with the United States, the Europeans also created a series of Western institutions, both defensive and economic. Slowly, they learned to share sovereignty. They not only created the International Monetary Fund in 1945 and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949, they also created the European Coal and Steel Community in 1951 and the European Economic Community in 1957. Kershaw notes that the existence of “the ‘other Germany’ provided ideological cement” for the West German republic. An awareness of the “other Europe” bound the rest of the West together too, helping to keep not only Germany but Italy and France, both of which had powerful Communist parties and strong currents of anti-Americanism, securely within the fold.

Advertisement

In the early years, this gigantic and unprecedented experiment in democracy and integration brought immediate benefits for all of the members of the West. What the French called les trentes glorieuses—the thirty years of steady growth and expansion of social benefits from the 1940s to the 1970s—had its echo elsewhere in the bloc. Germany had its Wirtschaftswunder, led by Adenauer’s finance minister, Ludwig Erhard; Italy had its boom economico, an extraordinary transformation that saw incomes double and triple within a generation. Even in the dictatorships of the Iberian peninsula, which did not join European institutions until the 1970s, postwar growth was remarkable: in Spain, GDP per capita rose by a factor of ten between 1960 and 1975. Growth and industrialization were accompanied by a parallel growth in social benefits: universal health care, free education, and government safety nets became the norm everywhere in Western Europe.

Economic success also inspired a cultural explosion. Kershaw devotes a chapter to postwar Western European writers, painters, designers, and directors, some of whom remained resolutely focused on coming to terms with the legacy of the war, and some of whom seemed bent on breaking with the past altogether. Listed here, country by country, it becomes clear what a powerful and diverse collection of people they were: from Günter Grass, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre to Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, the Beatles, and Christian Dior, European cultural figures gave Western European capitals a sheen of sophistication and glamour, as well as a clear identity in the cold war era that really was neither “American” nor “Soviet.”

By contrast, the history of Eastern Europe, in that same period, is one of failure, as is also made clear by Kershaw’s at times perfunctory summary of Eastern Bloc politics. In brief, the story of the region is the story of a series of political crises—in 1956, 1968, and 1981—followed by military interventions. Economically, the East also recovered and rebuilt, but much more slowly and much less completely than the West. Poland and Spain had roughly the same GDP per capita in 1950. By 1989, Poland’s GDP per capita had doubled—but Spain’s had gone up by a factor of five.

Culturally, there were many achievements too, but most of them—the films of Andrzej Wajda or István Szabó, the novels of Milan Kundera—were closely related to Western schools and fashions. The best of the Central European writers and artists influenced the Western conversation, and were influenced in turn by their Western contemporaries; certainly they did not aspire to be part of an alternative, Soviet world. On the contrary, they openly rejected Soviet models and undermined or mocked the strict “social realism” preferred by most of the region’s Communist parties.

This is not to say that Western Europe, in the postwar era, was any kind of utopia. The economic model did eventually stumble during the oil crisis of the 1970s. The political model hit multiple rough patches. There were challenges from terrorism in Italy and Germany, student strikes in France, workers’ strikes in Britain. There were constitutional crises, separatist movements, and bitter disputes between European leaders. Nevertheless, the lure of Western Europe, its prosperity, its culture, and the continental and transatlantic institutions built by Adenauer, Churchill, Jean Monnet, Robert Schuman, and a handful of Dutch, Belgian, and Italian statesmen, did become extraordinarily powerful. By the 1970s, the myth of “Europe” was strong enough to lure Spain, Portugal, and Greece away from dictatorship, toward democracy, and into European institutions—and even to persuade a reluctant Great Britain to join the European Economic Community. And, of course, it was powerful enough to send the iron curtain crashing down for good in 1989.

Americans usually remember the end of communism as the result of a binary battle between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, while most Europeans tend to see that era through the prism of their own national memories. Almost everyone downplays one of the most important sources of the Soviet empire’s collapse: the civilizational pull of Western Europe, as well as the transatlantic alliance to which it belonged. The Poles who voted for anti-Communists in June 1989, the East Germans who walked across the wall in November 1989, and the Czechs who protested in Wenceslas Square soon thereafter all wanted, as they told anyone who asked them at the time, to be “normal.” And they defined “normality” just as the West Europeans had in the 1950s: social market economics, liberal democracy, and American protection. They hoped that the EU would guarantee their prosperity, and that NATO could include them in the secure zone within which they too could flourish.

Advertisement

That was why, in the 1990s and 2000s, the nations of the East all sought to join Western institutions as fast as they could. Although, again, no one quite remembers it that way, the European accession process was by far the most successful democracy promotion exercise in history. Over a mere couple of decades, 90 million people and a myriad of political actors accepted dramatic changes: civilian control over the army, as required by NATO, and, in order to join the European Union, the establishment of an independent judiciary, laws on human rights, and a host of economic regulations. The new member states all agreed that to reestablish their national sovereignty after years of Soviet occupation, they would have to surrender some of that sovereignty to the various European institutions. Almost nobody objected. The choice made by Adenauer in 1952—in favor of liberal democracy and the tight integration of the West, and against nationalism and neutrality—was repeated by the Central Europeans, the Baltic states, and those Balkan nations economically advanced enough to qualify for NATO and the EU.

Kershaw’s book is a competent and comprehensive survey of Europe in the second half of the twentieth century, but if the book had ended in 2004, with Central Europe’s entry into the EU and the reunification of the continent, it would be difficult to see why it had to be written at all. After all, Tony Judt’s acclaimed Postwar, his 2006 history of postwar Eastern and Western Europe, covered much the same ground. The two books have quite a lot in common, including the unfortunate decision not to include footnotes or references. But Kershaw’s book has one important difference: it extends to 2017, and thus includes an additional decade—the decade during which most of the assumptions that the continent had long made about itself began to unravel. This gives him a rather different perspective.

Central to those assumptions was the belief in Western economic superiority. That was shattered by the financial crisis of 2008–2009, which had an outsized impact on Europe, destroying jobs, savings, and companies across the continent and particularly in the weaker economies of the south. Its psychological impact was just as significant: the widespread faith in Washington and Frankfurt—the belief that the bankers and the finance ministers must know what they are doing—was lost forever. Still, Europe survived it. As Kershaw writes, “The worst recession in eighty years had wrecked economies, toppled governments and brought turmoil to the European continent,” and yet “there had been no collapse of democracy, no lurch into fascism and authoritarianism…. Civil society, despite the traumas, had proved resilient.”

But the economic crisis was followed by another series of blows. Outside the cozy institutions of Europe, the world had been changing, and Europe’s foreign and security thinking had not kept up. Judt wrote, in 2006, that while Russia was a “decidedly uncomfortable presence,” it was “not a threat” to Europe. But even then this was no longer true, as Russia had already embarked on a major modernization of its military. Russia’s open return to old habits, including flagrant attempts to manipulate European politics, began again in earnest in 2007, with an effort to manipulate public debate in Estonia. That year saw the first use of a set of tactics that we now call “hybrid war”: a hyped-up political dispute over a Soviet-era statue of a Red Army soldier designed to enrage the Russian minority, an information war designed to unsettle Estonians, and cyberattacks on major Estonian institutions—all at the same time. The Russians would eventually use similar tactics in Georgia, Ukraine, and across a whole swath of European elections.

If Russia had returned as a foreign policy menace, the Middle East created some new threats. Europe seemed to have little ability to halt or control either the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2014 or the wars in Syria, Libya, Yemen, and Iraq. The latter helped feed a wave of horrific terror attacks—in Nice, Paris, Berlin, Manchester—that caused a major backlash against immigration, especially Muslim immigration, not only in Europe but all across the West. After the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, unilaterally decided to let in hundreds of thousands of refugees in 2015, the backlash intensified. The election in 2016 of the first US president since World War II to harbor an instinctive dislike of Europe solidified many Europeans’ fears that their institutions were not capable of coping with challenges to their security and to their borders.

The result has been a rise in both antidemocratic and anti-European political parties all across the continent, from the UK, France, and Germany to Hungary, Poland, and Estonia. Though they all have different origins and affiliations—some are anti-American and pro-Russian, some have religious roots, some are far right, some are far left—they share an “anti-establishment” rhetoric that is often profoundly cynical, given that many of these new party leaders are longtime pillars of the establishments they claim to hate. The leaders of the Brexit movement, which campaigned to take Great Britain out of the European Union, were anti-Europeans with long track records in British politics. But their rhetoric is now more effective, thanks both to growing fears of instability as well as new tools of social media that favor emotional and angry language over calm and reasoned debate.

In a sense, none of this is new: doubts about European values and concerns about European prosperity have haunted the continent for decades; Kershaw’s book is full of them. He writes of the “rise in the politics of identity,” for example, though of course this is another way of saying “the politics of nationalism,” a very old European story. Yet there is something different about the current doubts, precisely because they threaten to undo Adenauer’s decision to choose integration, just at the moment when the forces that shaped Adenauer’s generation—the memory of fascism, the faith in America and its democracy, the confidence in market economies—seem to be fading. Nobody now in political office has any real memory of World War II. A generation that does not remember the cold war either will soon be in power.

Something about the unexpected magnitude of the current crisis, its deep roots, and its lack of an obvious solution seems to have spooked Kershaw, who ends by wondering whether “the ghosts of the past [are] likely to return to haunt the continent.” But he doesn’t want to give an answer, and ends the book on a bland note: “The only certainty is uncertainty.” It’s as if he senses that the European story that seemed to have ended so well just a few years ago—with the Europe “whole and free” that so many wanted for so long—could yet go awry in unpredictable ways. It might soon need yet another reassessment, even more thorough than this one. What will we write about the second half of the twentieth century in the second half of the twenty-first century? Or even a decade from now? If success turns to dramatic failure, we will be digging back into this story once again to look for clues.