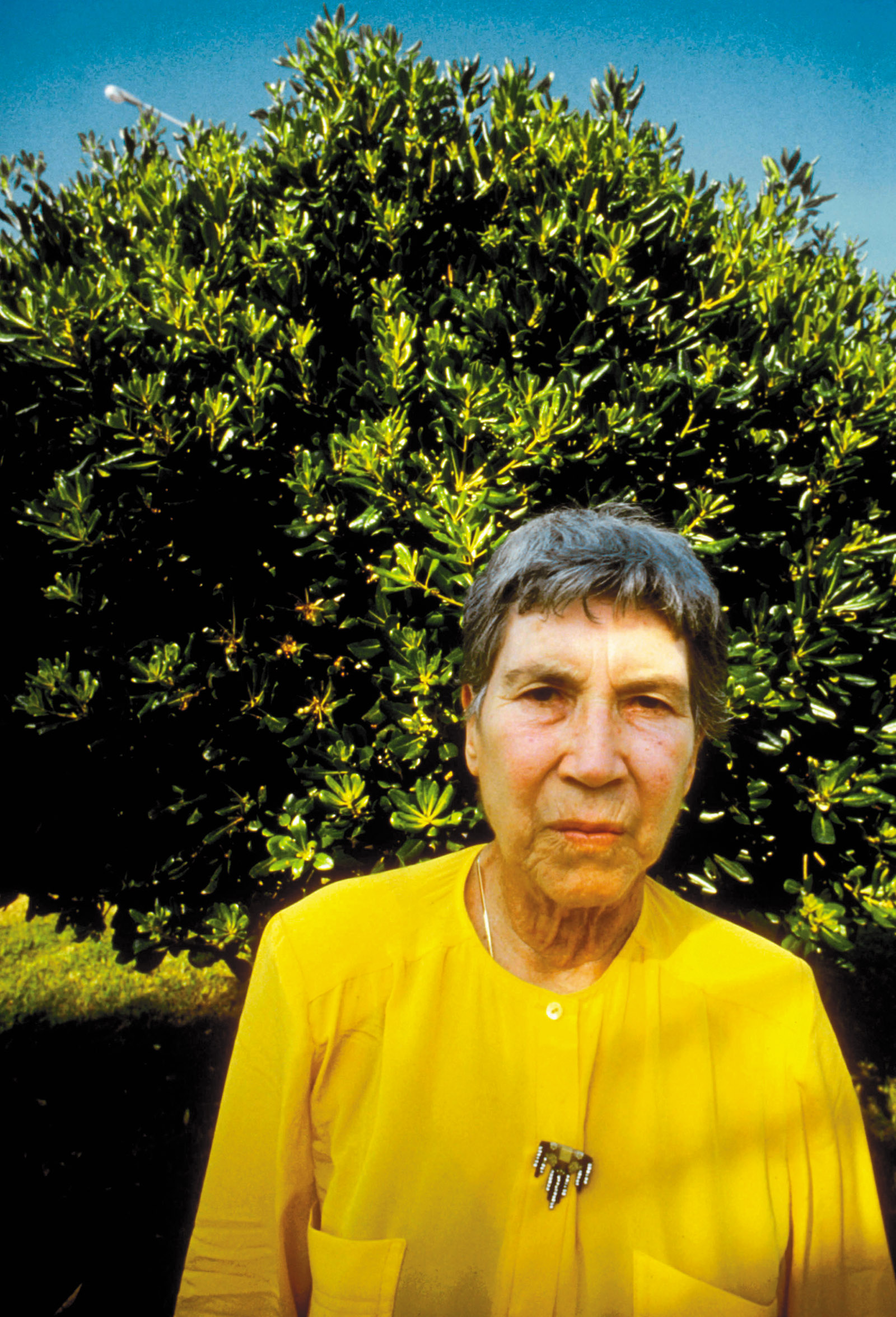

Natalia Ginzburg published her first novella, I Bandini, in 1934, when she was eighteen. Three years later she completed the first Italian translation of Marcel Proust’s Du côté de chez Swann. Over the course of her seventy-five years—during which she also worked as an editor at the Einaudi publishing house, brought up the four of her five children who survived infancy, served as a member of Parliament, and involved herself in humanitarian causes, including support for Palestinian children—she wrote novels, novellas, plays, short stories, columns, and essays. She was, in short, a born writer, and someone deeply engaged with the world she lived in.

If that world had been different, maybe the sparkling vivacity of her writing would have been uncomplicated by a menacing undertow of violence. But her father, Giuseppe Levi, was, as his surname made clear, Jewish, and her reasonably genteel middle-class family was left-wing. And as Fascism gradually engulfed Italy, Ginzburg and her family were increasingly beset, she herself most tragically.

These three books are very different, and each has its own translator, but Ginzburg is unmistakable. Her observations are swift and exact, usually irradiated by an unruly and often satirical humor. The instrument with which she writes is fine, wonderfully flexible and keen, and the quality of her attention is singular. The voice is pure and unmannered, both entrancing and alarming, elegantly streamlined by the authority of a powerful intelligence.

Her work is so consistently surprising that reading it is something like being confronted with a brilliant child, innocent in the sense of being uncorrupted by habit, instruction, or propriety. Ginzburg wastes no time, and the narratives can zoom around destabilizing hairpin turns. And yet the violence at the heart of each of these books is obdurate—immovable and unassimilable.

The novella The Dry Heart, published in Italian in 1947 as È stato così, is the earliest of these three books, and interestingly, perhaps, given the year, has no overt political content. Here’s how it begins:

“Tell me the truth,” I said.

“What truth?” he echoed. He was making a rapid sketch in his notebook and now he showed me what it was: a long, long train with a big cloud of black smoke swirling over it and himself leaning out of a window to wave a handkerchief.

I shot him between the eyes.

He had asked me to give him something hot in a thermos bottle to take with him on his trip. I went into the kitchen, made some tea, put milk and sugar in it, screwed the top on tight, and went back into his study. It was then that he showed me the sketch, and I took the revolver out of his desk drawer and shot him between the eyes. But for a long time already I had known that sooner or later I should do something of the sort.

How quickly the author has presented us with an entire character! It takes less time to read this opening than it would have taken Alberto to make his rapid, feckless, goading sketch. What follows is devoted to how, exactly, we’ve arrived at this pass, but before we’ve read any further than this, our allegiance is already with the murderous wife (who has, after all, shown some restraint). And that allegiance is only fortified the better we get to know the victim.

Alberto is not an especially unusual man, I think, and yet I’ve never encountered a man like that on the page, or anyhow never one rendered so vividly, with such ferocious humor and insight, in all his emotional shallowness, the maddeningly casual quality of his exploitations, his childish, ruthlessly irresponsible dependency and sporadic displays of affection, his stunning self-involvement. Of course, it actually does take two to tango—and who would marry this man, one might wonder, other than the most pathetic dupe? Well, just have a look around at some of the stellar women you know.

At the time she meets her future husband, the nameless narrator is a small-town schoolteacher whose capacities are underutilized in her job. She lacks the luxuries of time, choice, and self-confidence that her glamorous, good-looking, well-to-do younger cousin Francesca has, and although at first she has no interest whatever in the much older Alberto, soon boredom makes her—like so many women whose prospects are threadbare—vulnerable to hope. She misconstrues his aimless attentions as attraction and gradually comes to crave that small excitement—her only excitement—and trades her autonomy for it irretrievably.

While the narrator’s miseries are fertile ground for sentimentality and melodrama, Ginzburg’s uncompromising vision shears the story of both: that’s how it was, she essentially says—and it’s not going to get better. The narrator makes no claims on us; we are not wheedled into “identifying” with her or despising her dreadful husband. We observe the protagonists with the equilibrium of clarity—the wife in her barren cage of isolation and irremediable grief, and the husband in his barren cage of self.

Advertisement

This command of tone—of attitude, let’s say, and vantage point—is just as remarkable in Happiness, as Such, originally published in Italy as Caro Michele in 1973 and set contemporaneously. It’s a freer book, looser and stranger, formally, than The Dry Heart, and its characters manage, for the most part, to muddle along, as the English-language title suggests. From the Italian title you’d guess that it’s an epistolary novel, and it largely is, though parts of it are in the third person.

It’s always pleasurable to read a good epistolary novel. Particularly when, as in this one, there are letters between more than two characters. Information flies around, attitudes are baldly expressed or conspicuously disguised, opinions and interpretations ricochet, splatting against this or that, and personalities are magnified by contrast. And as these are Italians, the personalities are plenty big to begin with. Here, for example, is part of a letter to Michele from a young woman named Mara:

March 26, 1971

Dear Michele,

I had dinner at your mother’s house a few nights ago. It was not fun. Osvaldo and Angelica were there, and the pelican, your aunt, your mother, and your little sisters. I don’t know why I wanted to meet your mother and wanted her to like me. Maybe because I was hoping that she’d help me get you to marry me. To be clear, I’ve never wanted to marry you. Or at least I never thought that’s what I wanted. But maybe out of desperation I wanted that without knowing that I did.

I wore a long black and silver dress that the pelican had bought for me that same afternoon. And a mink coat that the pelican also bought for me five days ago. I kept the coat on all night because your mother’s house is so damn cold. The thermostat is defective. Wearing that dress and coat made me feel legitimate, I can’t explain why. It made me feel sweet, and ever so small. I wanted everyone to look at me and think how sweet and small I am. I wanted this so badly that when my voice came out of my mouth it was sweet and gentle. And then, at a certain point, the thought occurred to me, “These people probably all think that I’m just a high-class call girl.” The phrase, high-class call girl, is something I’d read in a mystery novel that morning. As soon as I thought up those words I could feel them falling down on me like stones….

Your mother and Angelica were busy in the kitchen because your mother’s housekeeper suddenly got sick and had to go to bed. The truth is, she was offended by something your aunt had said about her vol-au-vent. That’s what Angelica told me. Your little sisters refused to help because they said they were too tired, and played ping-pong instead. They were still wearing their gym clothes and refused to change and that made your aunt angry too. That, on top of the vol-au-vent being all mushy and liquid inside.

I started getting depressed at a certain point. I thought, What am I doing here? Where am I? Why am I wearing a fur coat? Who are these people who don’t ask me practically anything and can’t seem to hear me when I speak? I told your mother that I wanted to bring my baby over to meet her. She said I could but didn’t seem enthusiastic about it. I was dying to start screaming about how the baby was yours. If I was a hundred percent sure I would have.

You also might guess from the Italian title that there’s an elegiac undercurrent to the book, and that would be correct, too: elegy first for the dissolution of a marriage and a family, then for the dissolution of a love affair, then for the victim—once again—of murder.

This time the murder victim, whom we never come entirely to know or to comprehend well, is at the center of a constellation of characters and is the object of their concern, speculation, irritation, love, and longing. And rather than being all but inevitable, the murder is bewilderingly random: the young man has apparently attended a student protest in Bruges where he was chased by a group of fascists, stabbed, and left to bleed to death in the street. “They might have recognized him from somewhere,” his sister Viola writes in a letter.

Advertisement

Blurry and distant, this idiotic killing is an unexpungeable vestige of the Fascist takeover of Italy, the terrible years of the war. In fact, you could say that an elegy for an entire historical period pulses here under the foreground of daily life, the daily concerns of the living—irritations, pleasures, disappointments, dramas, friendships, confusions, sorrows, meals…What’s generally considered small or mundane, even negligible, looms large: the usual scale of a story is reversed.

Candor and lies, love and exasperation, farce and inconsolable grief are seamlessly compounded in this very funny and deeply melancholy book. After devastating loss, which is to be feared more greatly—that nothing will ever be the same, or that many things will be more or less the same? Life goes on, all too recognizably. “You can get used to anything when there’s nothing else left,” says one of the characters toward the end.

Ginzburg’s dexterity is perhaps most spectacularly employed in her memoir, Lessico famigliare, entitled Family Lexicon in its most recent English-language translation. Ginzburg included a preface, which reads in its entirety:

The places, events, and people in this book are real. I haven’t invented a thing, and each time I found myself slipping into my long-held habits as a novelist and made something up, I was quickly compelled to destroy the invention.

The names are also real. In the writing of this book I felt such a profound intolerance for any fiction, I couldn’t bring myself to change the real names which seemed to me indissoluble from the real people. Perhaps someone will be unhappy to find themselves so, with his or her first and last name in a book. To this I have nothing to say.

I have written only what I remember. If read as a history, one will object to the infinite lacunae. Even though the story is real, I think one should read it as if it were a novel, and therefore not demand of it any more or less than a novel can offer.

There are also many things that I do remember but decided not to write about, among these much that concerned me directly.

I had little desire to talk about myself. This is not in fact my story but rather, even with gaps and lacunae, the story of my family. I must add that during my childhood and adolescence I always thought about writing a book about the people whom I lived with and who surrounded me at the time. This is, in part, that book, but only in part because memory is ephemeral, and because books based on reality are often only faint glimpses and fragments of what we have seen and heard.

In view of this preface, it’s especially startling that the book won the Strega Prize for fiction when it was published in 1963. My own conviction that there is an irreconcilable difference between things that are factual and things that are not—or, in other words, between fact and fiction—now seems more than quaint. But certainly it would now be even more surprising to give a fiction prize to something purely factual than to give a journalism prize to something made up out of whole cloth.

It could be that it was patently inarguable that Ginzburg deserved Italy’s most prestigious literary prize for this marvelous book, whatever the prize happened to be. Or it could be that the distinguished judges couldn’t bear to accept that what Ginzburg adamantly presents as fact was indeed fact. Or, more neutrally, it could be that Family Lexicon is so original that it couldn’t be maneuvered into any category other than fiction—and, after all, she said she thought one should read it as if it were a novel.

There are welcome notes provided by the translator, Jenny McPhee, and a welcome afterword by Peg Boyers, the executive editor of Salmagundi, for which she once interviewed Ginzburg. Nonetheless, if you’re looking for facts about Ginzburg and her life—or even if you just want a firm grip on exactly what happened exactly when—you might be better off crawling around online; although Ginzburg’s account is essentially chronological, it conforms to the prioritizations of memory and the logic of feeling, with its oblique and subterranean connections. We feel, in an immediate and intimate way, the sensation of change, of changing relationships and changing times as Ginzburg and her siblings grow up, her parents age, and history demands new adaptations and sacrifices and elicits from individuals unexpected characteristics. The lacunae to which she refers are generally not omissions so much as critical detours around mined, desert, or sacred territory.

Ginzburg had four older siblings—Gino, Mario, Alberto, and Paola—in a lively Torinese family. It is her outsize father, Giuseppe Levi, known as Beppino, whom we meet first, and he takes up all the space, as he would have to a child, storming and ranting like a comic opera tyrant. Despite being a scientist, he initially appears to be totally irrational—anarchically domineering, preposterous, intolerable and completely intolerant. And like many people who are quick to criticize, he embodies various qualities he denounces in others:

“He struck me as a real nitwit,” he would say about some new acquaintance.

In addition to the “nitwits,” there were also the “negroes.” For my father, a “negro” was someone who was awkward, clumsy, and fainthearted; someone who dressed inappropriately, didn’t know how to hike in the mountains, and couldn’t speak foreign languages.

Any act or gesture of ours he deemed inappropriate was defined as a “negroism.”

“Don’t be negroes! Stop your negroisms!” he yelled at us continually….

We were never allowed to stop for a snack in the mountain chalets as this was considered a negroism. Protecting your head from the sun by wearing a kerchief or a straw hat, or from the rain with a waterproof cap, or tying a scarf around your neck were also deemed negroisms. Such preventive wear was, instead, precious to my mother, and the morning before we left on our hike she would try to slip these things into a rucksack for both our use and her own. If my father laid his hands on any of them, he would angrily throw it out.

McPhee provides an interesting note on the words “negro” and negrigura, which she translates as “negroism.” And in answer to the assertion by an expert on Venetian-Jewish dialect that negrigura simply was used to mean “foolish thing” and “never had overtly racial content,” she says, “Ginzburg, however, was very aware of the words’ racial significance and her deliberate placement of these terms on the opening pages of her novel resonates throughout the book.”

Certainly, to assert that a term of that sort—like “welshing” on a deal or “jewing” someone down—expresses no particular prejudice is the feeblest sort of sophistry, and in any case the hallmark of the period about which Ginzburg is writing was racism. A mist of love and gratitude for Italy—for the general warmth of the people, for their expressiveness, for their spaghetti—tends to obscure from our awareness certain historical facts and urges us to imagine that anti-Semitism was a stance rejected even by Fascist Italians. But this was not at all the case.

Even though it is true that the “racial laws” were not instituted in Italy until 1938, and that many Italians sustained or hid Jews, and that Italy seems to have imprisoned, tortured, and deported to Germany a smaller proportion of its Jews than most other European countries, nonetheless plenty of Jewish blood flowed there. And that would have been understood by readers of Ginzburg’s memoir at the time it was published.

Although Beppino, like his wife and children, was staunchly and even courageously anti-Fascist, he himself was not entirely immune to prejudicial views about Jews. It is when his light-hearted and energetic wife, Lidia, decides to study Russian to amuse herself that we are introduced to the Russian-born Leone Ginzburg, whom the author eventually married and under whose name she wrote:

“What’s Mario doing with that Ginzburg?” [Beppino] asked my mother….

“He is someone,” my mother said, “who is very sophisticated, intelligent, translates from Russian, and does beautiful translations.”

“But,” my father said, “he is very ugly. Jews are notoriously ugly.”

“And you?” said my mother. “You’re not Jewish?”

“I am, in fact, ugly too,” my father said.

Strangely, personal beauty is a hotly contested issue in the household:

We had endless discussions over whether the Colombos or the Cohens…were uglier.

“The Cohens are uglier!” my father shouted. “You want to put them in the same category as the Colombos? There’s no comparison! The Colombos are better-looking! You’re blind if you can’t see that! You lot are blind!”

Of his various cousins called either Margherita or Regina, my father would say they were very beautiful. “As a young woman Regina,” he’d begin, “was a great beauty.”

And my mother would say, “But it’s not so, Beppino! She had a jutting chin!”

She’d then demonstrate Regina’s protruding chin by sticking out her own chin and lower lip, and my father would get angry. “You don’t understand a thing about beauty and ugliness! You say that the Colombos are uglier than the Cohens!”

You might think that with all the squabbling, which included some real knock-down-drag-outs between Mario and Alberto when they were children, the household would have been a nightmare. But clearly it’s not only from a distance, through the tempering of time and Ginzburg’s remarkable ear, that it seems so funny and so enjoyable. It surely was, probably most of the time. Lidia was sunny, inventive, and optimistic. It’s evident that in their different ways both she and Beppino loved each other and their children. There were friends and books and stories and songs, and although Beppino scoffed and raged, his scorn seems to have been less a matter of substance than the habitual application to everything of his eccentric—supposedly high—standards. His dictates were often ignored, as were his objections to the marriage of each of his children. And anyhow, the hail of exclamation points was coming down from almost every member of the family.

Although most of the family was eventually involved—generally unbeknownst to one another—in clandestine anti-Fascist activities, what truly unites them in Ginzburg’s portrait are certain words or turns of phrase derived from repeated anecdotes, often told by Lidia, whose idiosyncratic aural sensitivity to the odd detail seems to have been passed along one way or another to her children:

A lot of her memories were like this: simple phrases that she overheard. One day she was out for a walk with her boarding-school classmates and teachers. Suddenly one of the girls broke rank and ran to embrace a passing dog. She hugged it and in Milanese dialect said, “It’s her, it’s her, it’s her, it’s my bitch’s sister!”…

My mother…would turn to one of us at the dinner table and begin telling a story, and whether she was telling one about my father’s family or about her own, she lit up with joy. It was as if she were telling the story for the first time, telling it to fresh ears….

And if one of us said, “I know that story! I’ve already heard it a thousand times!” she would turn to another one of us and in a lowered voice continue on with her story….

Those phrases are our Latin, the dictionary of our past, they’re like Egyptian or Assyro-Babylonian hieroglyphics, evidence of a vital core that has ceased to exist but that lives on in its texts, saved from the fury of the waters, the corrosion of time.

But eventually there were new words and phrases:

We’d say, “We can’t invite Salvatorelli over! It’s compromising!” and “We can’t keep this book in the apartment! It could be compromising. They might search the place again!” And Paola said the entrance to our building was “under surveillance,” that there was someone always lurking out there wearing a raincoat and that she felt she was being “tailed” whenever she went out.

Beppino and Lidia continue poignantly to hope for Fascism simply to disappear in a puff of smoke. But instead, even old friends become Fascists. The family is increasingly isolated. Escapes, arrests, terror, internal exile, and prison begin to permeate “ordinary” life. The drama would dominate in a conventional memoir, but again the scale in which we’re accustomed to think of things is reversed; we see the nightmare as if from behind a veil of the diurnal. And when we learn of Leone’s death, presumably by torture, in the Regina Coeli prison in Rome, it is glancingly—as fleetingly and quietly as we learned of his existence and then of his marriage to Natalia—as though the memory of him were too delicate and precious to be subjected to light.

The war took a toll on Ginzburg’s parents:

The terror and tragedy caused my mother to age suddenly, overnight…. She was always cold because of her fears and sorrows, and she became pale with large dark circles under her eyes. Tragedy had beaten her down and made her despondent, made her walk slowly, mortifying her once triumphant step, and carved two deep hollows into her cheeks.

In time, though, Lidia’s ultimately irrepressible joyfulness has her again telling the familiar stories, and we feel the wheel of ordinary life turning again, humming along.

But behind that wheel, as in the fictional The Dry Heart and Happiness, as Such, is another wheel:

During fascism, poets found themselves expressing only an arid, shut-off, cryptic dream world. Now, once more, many words were in circulation and reality appeared to be at everyone’s fingertips. So those who had been starved dedicated themselves to harvesting the words with delight. And the harvest was ubiquitous because everyone wanted to take part in it. The result was a confused mixing up of the languages of poetry and politics. Reality revealed itself to be complex and enigmatic, as indecipherable and obscure as the world of dreams. And it revealed itself to still be behind glass—the illusion that the glass had been broken, ephemeral.

I was born in 1945. Until astonishingly recently, I and most, I suppose, of my contemporaries, believed that fascism had been vanquished. That illusion, too, was ephemeral—the wheel turned. It could be—given, in addition to the international resurgence of fascism, extreme climate change and resulting mass migrations, the pressure of an increasing population on the food supply, and the mass extinction of species—that the wheel will never again turn to the point where Lidia could resume telling her stories. But while we are waiting, and hoping against hope, the writing that Ginzburg has left behind shines in the dark, sharpening our view to what’s behind the glass, enigmatic and obscure and right in front of our eyes.