Gavin Lambert’s The Goodby People is set during the inexhaustibly fascinating few years preceding its original publication in 1971, in the city of Los Angeles, where the earth trembles and the hedonistic sun shines no matter what. Though the fantasies it churned out for some decades had branded the psyche of the world, the rigid Hollywood studio system, with its iron grip over all aspects of the US movie industry—and the piously punitive high moral tone it adopted during the 1940s and 1950s of anticommunism, “family values,” and homophobia—was then completing its retreat into the past. The Vietnam War was in full, gruesome swing, and for many young white Americans, it was a seriously disorienting experience to have their self-flattering sense of a noble national identity shattered by their government’s savagery against distant, largely agrarian people of color, in ostensible pursuit of “democracy” on their behalf (bitter ironies of which so many Black Americans were already fully, and vocally, aware).

The spectacularly volatile compound of place and moment was exploding into galaxies of potentialities that invited psychological exploration, social experimentation, abrupt life transitions, and exuberant or desperate adventure. Resting points along the careening journey to somewhere else tended to be unstable and precarious, and great numbers of young people were fleeing the complacently materialistic middle class, preferring to live on one brink or another, many of which overlooked the Pacific Ocean.

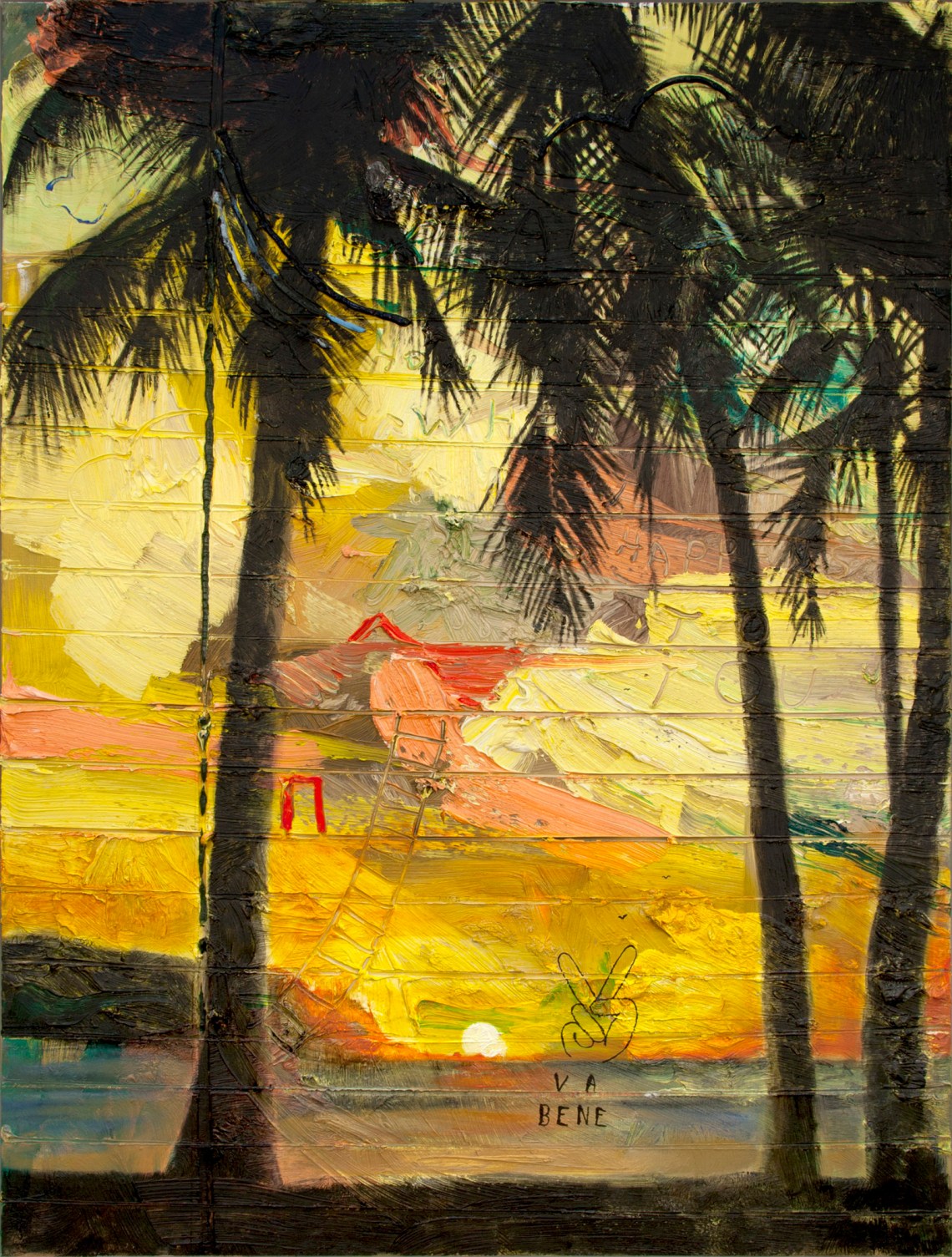

The Goodby People captures these evanescent phenomena on the wing, and the book is alive with a heightened sensitivity to scarcely articulable aspirations of the time, as if Lambert wrote it wearing some sci-fi-type helmet with tubes and wires that conveyed directly into his brain and pages the plasma of a culture turning from one thing into another, and the exhilarating, terrifying, beautiful, and pitiable weirdness of human life when it’s let off its leash. Like Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust and the Bud Wiggins novels of Bruce Wagner, The Goodby People is irradiated by the inherently metaphorical properties of Los Angeles—the fantastical jumbles of architecture encrusting the enduring drama of hills and ocean; the subtropical vegetation entangled in the pollution-enhanced sunsets; the studio approximations of civilizations that rise, fall, and are sometimes forgotten within months; the dizzying drops from pinnacles of success into abysses of failure—that hint insistently at revelation and prophecy.

Lambert was born in England in 1924 to strictly conventional upper-middle-class parents. His infatuation with movies struck when he was eleven. That was also the age at which he understood that he was gay, which in England, where male homosexual acts had been prosecuted as criminal offenses since 1533, called for caution or courage or both. In 1943 he enrolled at Magdalen College, Oxford (from which Oscar Wilde had graduated with honors some years before he was imprisoned, in 1895, at the height of his popularity, for sodomy and gross indecency). Lambert allegedly disliked his English literature tutor, C.S. Lewis, and dropped out of university after a year.

In the online encyclopedia GLBTQ Archives, Linda Rapp recounts the circumstances of his exit: the president of Magdalen summoned him and his parents to a conference and announced that not only did Lambert skip tutorials but he also picked up GIs and brought them back to his rooms. Not so! Lambert protested; he’d only picked up one. Rapp also tells how Lambert evaded military service without having to declare to the draft board that he was gay: when asked why he was wearing gold eye shadow, he answered, “‘A friend of mine likes it,’ and was promptly classified 4F.”

In 1947, along with his university friends Penelope Houston, Lindsay Anderson, and Karel Reisz, all of whom became significant figures in cinema, he founded an influential film journal, Sequence. When Sequence folded, which it did a few years later, Lambert went on to edit the likewise influential but much hardier journal Sight and Sound.

As for so many others, Europeans and English, the luxurious climate of Los Angeles was a refuge and the excitement of Hollywood an irresistible lure, and in 1956 Lambert left the country he found so stifling, along with his unloved de facto class membership, to work with the director Nicholas Ray. For a time he was Ray’s assistant, as well as one of his screenwriters and—also like so many others (mostly female)—one of his lovers.

The novel is composed of five sections—a brief prologue and a brief epilogue surrounding three parts entitled “Susan Ross,” “Gary Carson,” and “Lora Chase,” each a fictional person who occupies a substantial place in the thoughts and affections of the clearly not all that fictional unnamed narrator.

Susan has recently been widowed. Her late husband, Charlie Ross, was a movie producer for whom the narrator sometimes wrote screenplays. Charlie and Susan met while she was a high-fashion model in the early 1950s, when the taste “was for mystery. They photographed Susan in empty rooms, on the edge of long shadows, leaning against ruined walls or descending a flight of lonely steps.” Owing to her extraordinary beauty, her preternaturally youthful appearance, and the real age difference between the two, “all the usual explanations were advanced” to account for the marriage: “However, you couldn’t be in a room with them without noticing that he adored her and that Susan was at least very happy. If he left the room, she looked abandoned.” Charlie

Advertisement

had a dry disenchanted humor, a fascinating inside knowledge of shady political deals and the secrets of the Pentagon and the FBI, and that aura of joylessness which surrounds so many rich, powerful and clever people and makes them truly dangerous. They want you to know they’re lonely and vulnerable underneath it all. I’m afraid it was this quality that attracted Susan, for she could talk in the same way about the loneliness of being beautiful.

Susan’s father was a ranch hand, apparently illiterate, and her mother a cook and housekeeper at the same ranch. They were unhappily married, then not married, and Susan grew up in Nebraska and Arizona and various other places, “moving farther into space, vastness, clear and lonely air.” Having been discovered at fifteen by a photographer, she was never really educated, but she has always been a reader, and reads “in definite cycles, the way people do when they search literature for ‘answers.’” When we meet her, she’s reading, among others, Jung, Hesse, and Aldous Huxley.

After Charlie’s funeral, “the usual spectacular funeral, as catered as a party,” Susan disappears: “One heard sentimental and outrageous rumors, as one heard them when she married Charlie.” The narrator keeps in touch with Susan intermittently, though it isn’t easy. She has the money to follow any impulse, and her impulses take her places where she apparently hopes to feel as insulated as she felt with Charlie. Houses and household staffs are rented and left, phone numbers are changed, friends are fled from, she’s always late, and she drives very fast. Does she notice anything as she’s driving fast, the narrator asks, “or is it all just a blur?”

“Just a blur! And if you’re always late, you don’t really want to go where you’re going, anyway.” She got up and stretched out her arms, as if on an imaginary cross. “‘On the way to where she didn’t want to be, she noticed nothing at all.’ Maybe I’ll put that on my grave.”

And what exactly did she feel when she was with Charlie? the narrator wants to know. She looks surprised: “I didn’t feel lonely. That’s what I felt.”

The narrator’s last visit to Susan is—possibly—poorly timed. Her compulsive habit of keeping people waiting results in the arrival soon after the narrator of her new suitor, who is obviously displeased to see someone with her. She walks the narrator to the door, and they linger briefly under the “stony” eye of the suitor’s bodyguard:

Her hand rested on mine for a moment. It was icy cold. Yet she went on smiling. “Did you know that when people get lost in rain forests and jungles and difficult places like that, they always go in the wrong direction and get lost even further, because they panic? It’s a fact,” she said brightly. “I read it somewhere. They think they’re finding their way back, but…they’re really getting lost forever.”

The novel’s narrator, like Lambert, is a diligent writer, and what diligent writers do all day isn’t all that interesting to a spectator. Fortunately, though, there seems to be no end of parties for us to go to. The parties in “Susan Ross” are agleam in soft reflections of pool lights, atinkle with ice in highball glasses, and rich in sparkly guests.

In contrast, the party that opens “Gary Carson” is a small dinner of drifty young people at the warehouse loft of the narrator’s friend Loney, in a run-down area east of Hollywood not zoned for residential buildings. Loney is an artist, but his real calling is

sheltering young wanderers and fugitives…. There are usually eight or ten people sleeping around the loft. Loney sometimes forgets exactly who is there. A stranger rises suddenly from an alcove bed, Loney fixes him with pale, astonished eyes, his babyish, fortyish face lights up and he says, “Oh, what a nice surprise! Now who are you?”

The house rules are cleanliness, peacefulness, and no hard drugs. Loney is invariably fond and proud of his charges, and asks nothing in return for tending them. “Doesn’t there have to be a halfway house between Haight-Ashbury and summer camp?” he reasons.

Advertisement

Arriving late to dinner on this particular evening is

a very tall, astonishingly handsome young man…. There was a Viking air about him, something of the pirate and the hunter. You could tell that he was, so to speak, the star boarder…. He looked at me very steadily, with a kind of ironic penetration….

From the first, I believe, he sensed a link between us…. When I said something, he answered noncommittally and turned away—not to dismiss me, but as if for some reason I made him unsure of his ground.

The young man looks oddly familiar—oh, yes: one day, driving on the highway, the narrator had glimpsed a chauffeured car he thought he recognized as Susan’s stopping to pick up a very tall, astonishingly handsome hitchhiker.

Gary has been dodging the draft for two years. A girl recently took him to Mexico, and he’s been going back and forth between LA and Japan courtesy of a freighter captain he met somewhere. He seems to have been living with some girl, presumably a different girl from the one with whom he went to Mexico, but…

He is increasingly restive. When the narrator asks whether he has considered being a conscientious objector, Gary advances impassioned but somewhat specious arguments about why he has rejected that solution. And when the narrator suggests that Gary himself might have engineered a situation in which he feels entrapped, Gary is irritated, but also apparently refreshed to meet someone who isn’t too dazzled by him to be frank.

A week or so later, Gary calls. “Do you remember me?” he asks; he’s in the neighborhood, he could drop by. He arrives somewhat buffed up and mentions in the course of conversation that it’s impossible to stay too long at Loney’s: “It’s depressing. You begin to feel you’re part of some underground freak show. The bag closes too tight.” All right, yes, so Gary can stay.

The narrator mostly keeps to the background, but in the affair that follows with Gary, we see very much the person we saw as Susan’s friend: interested, amused, concerned, but fundamentally an observer. When Gary, who has been emanating the glamorous unpredictability of an exotic pet, predictably leaves, it seems almost that it’s because he wasn’t able to command the narrator’s unreserved attention, though it’s clear that if he had succeeded in doing so, he surely would have felt suffocated and left anyhow. He says:

I really am glad I met you, and I know you feel the same about me. I may not be the ideal guest, but the great thing about being a guest is, you’re bound to win one way or the other. Either they’re happy to see you arrive or happy to see you go. Right?

When the narrator asks Susan about having picked Gary up on the highway, she dismisses the question out of hand: no, no—she never picks up hitchhikers. But when Gary is asked—although he is usually vague to the point of misleading about his relations with women—he recounts the story of a sweetly anguished night, which is not particularly flattering to either of them. Still, although they spent very little time together, Susan and Gary have a lot of common ground.

Some especially beautiful people seem to derive comfort from the visibly teeth-gnashing, blood-boiling effect that their boastful, snake-mean lamentations have on others. (“You’re so lucky that you’ll never know the pain of being loved for your beauty,” a gorgeous woman once said to a friend of mine.) But such lamentations sometimes reveal an actual agony of insoluble ambivalence. Susan seeks the isolation that she complains is imposed by her beauty; Gary deeply distrusts the value of the attention he automatically receives, but at the same time he construes the attention as the measure of his value. Are they cheating, or cheated? Whichever it is, their unearned special status is so tightly woven into the fabric of their selves that both live in mortal terror of the slightest sign of wear and tear to their glorious façades.

Susan’s search for safety is, like everything else about her, hers alone. Gary, some twenty years younger, searches for safety in the more communal way of his generation. Late in their relationship he and the narrator drive, at Gary’s urging, up the coast for a concert, where a mass of thousands has been gathering since the early morning. Even to the unlikely reader who doesn’t recognize shadows of the 1969 Altamont concert, the event would be unmistakably ominous. And some months later, Gary invites the narrator to visit him at a remote compound where the group’s leader, Newt Godson, rambles on with counterfeit humility and exalted incoherence. The threat of violence and incipient authoritarianism in both places is only lightly camouflaged; in hindsight, it’s very clear that the bright era could turn inside out at a touch, and toxic material is already leaking from its core, staining everything.

The air of the so-called 1960s—the air that the book’s narrator and its other characters breathe—shimmered with notions of synchronicity, fated coincidence, the workings of dimensions unavailable to human perceptions, and so on, derived largely from the writers Susan has been reading, from Zen Buddhism, and from various other mystical and quasi-mystical sources soaked in a concentrated solution of pop science, pop philosophy, and drugs. There was an intense, general longing to locate hidden escape routes from what seem to be the inflexible laws of the universe, or at least from the limitations of our consciousness. Although it’s natural enough (sort of) that the main characters would run into one another, even in vast and, to use the narrator’s expression, “tribal” Los Angeles, the concurrences have a slightly uncanny, haloed feel, as if they were evidence of fundamental vectors revealed to the senses only under highly unusual conditions.

But the more extreme imponderables of place and time perform their real fireworks in “Lora Chase,” the story of a very eccentric triangle—or something with a few more angles than that—between the narrator, a young woman named Keelie Drake, and Chase, an enigmatic movie star of an earlier period.

At yet another party, a casual Sunday drop-in thing, one of the guests, Keelie, unsuccessfully struggles to explain her disdain for “real things, facts, situations.” Her interlocutors are bored, but the narrator recognizes her as someone he once glimpsed leaving a place where he came to visit Gary, and he strikes up a conversation with her. She mentions that she’s renting a guesthouse way up in the hills. The main house, which apparently belongs to somebody named Lora Chase, is a bit spookily vacant. But what’s really weird is that a beautiful woman, who turns out to be Chase, started appearing to Keelie when her eyes were closed, even before she rented the place or learned who its owner was!

The narrator is thunderstruck—and not just because Keelie claims to have a visitant. No, it’s also because every day when he was an eleven-year-old schoolboy in London, he would pass a billboard featuring a solitary figure, the actress Lora Chase, walking “away along an empty road, under a bare white sky, toward a blank horizon. She wore black. Below, in huge sloping elongated letters: ON THE ROAD TO GOD KNOWS WHERE.” He went to see the movie by himself

on a cold Saturday afternoon and was spellbound by the actress, who was beautiful in a rather fine, aristocratic way and far more mysterious than the woman she played. Her voice had a smooth low quality somehow perfectly pitched for lying. She was passionate without being explicitly sexual…. And no matter how candidly, longingly she rested her eyes on an actor in a scene, or on myself in one of those direct staring close-ups with music, she gave the impression of really watching something or someone else beyond, farther away, out of reach.

Rumor has it she became an alcoholic, then a Catholic, then she disappeared entirely. During the narrator’s first years in Hollywood, he tried desperately to locate her, but the trail inevitably went cold. Does Keelie know where she is?

No, Keelie says—she rents through an agent. But why, asks Keelie, is this Lora Chase picking on them? Why does Lora appear to her, why did Lora bring him to Hollywood? The narrator tries to disentangle himself: Lora Chase did not bring him to Hollywood! he objects. He came to Hollywood, it had nothing to do with her. But the reader is bound to see that Keelie has a point.

Keelie herself has come to Los Angeles courting freedom and experience. The earnest, motorcycle-riding, rather goofy girl, who supports herself, insofar as she does, by working at a vintage store and as a bottomless dancer, seems in many ways an unlikely choice for the elegant, mysterious Lora to channel herself through. But the corporeal, still-living Lora Chase, whom we, and the two characters so tied to her, eventually encounter, seems in some ways an unlikely development from the much younger, on-screen version of herself—a Hollywood dream-factory person, a person who might have never exactly existed.

Obviously The Goodby People doesn’t directly address the question of How We Got from Then to Now; there was no Now then. But incursions into the present from both the past and the future zoom here and there throughout the book, and Lambert was clearly contemplating the journey that his complex, conflicted, gallant, departing characters ON THE ROAD TO GOD KNOWS WHERE were embarking on as they said good-bye.

Lambert was prolific as well as diligent. In addition to his screenplays and numerous articles for periodicals, he wrote seven novels, a collection of short stories, and biographies. He also directed one movie, Another Sky, set in Morocco, where he moved in 1974. He stayed mostly in Tangier until 1989, when he returned to Hollywood, where he died in 2005. Whatever he might have felt about the American movie business and Los Angeles over the course of the many years he spent there, it seems that his appetite for movies endured, as did the alert, enchanted gaze of the stranger toward a true, longed-for home.