The word museography properly refers to the systematic description of objects in museums, but it might also do for the culture and ideology surrounding that dusty old figure of legend, the artist’s “muse.” If her aura is fading now, anyone educated during the twentieth century remembers when she played no small part in our curricula, both formal and informal. (The male muse, back then, existed only in the homosexual realm.) To avoid her, you had to spend a lot of time in libraries seeking evidence of her opposite: not the sitter but the painter; not the character but the author; not the song but the singer. And a few women did appear to have avoided the state of muse-dom: Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, Zora Neale Hurston, Patti Smith. In fact, such women could be said to have acquired muses themselves, or to have been involved in a mutually beneficial muse-ology with other artists (Vita Sackville-West, Alice B. Toklas, Langston Hughes, Robert Mapplethorpe). But it was slim pickings.

Meanwhile, in the annals of museography, you could discover a celebrated parade of handmaids to the genii, “legendary beauties,” ladies with salons, chic ladies, witty ladies, ladies with inspiring ankles, faces, breasts, voices, clothes, attitudes, houses, and inheritances; women whose brilliant conversation had been entombed in various novels; women whose personal style had prompted whole fashion houses into production; women whose tenure as girlfriend or wife usefully demarcated the various artistic “periods” of the male artists with whom they’d been involved, even when those women were also, themselves, artists. The Yoko Years. The Decade of Dora. Accounts of the muse–artist relation were anchored in the idea of male cultural production as a special category, one with particular needs—usually sexual—that the muse had been there to fulfill, perhaps even to the point of exploitation, but without whom we would have missed the opportunity to enjoy this or that beloved cultural artifact. The art wants what the art wants. Revisionary biographies of overlooked women—which began to appear with some regularity in the Eighties—were off-putting in a different way (at least to me). Unhinged in tone, by turns furious, defensive, melancholy, and tragic, their very intensity kept the muse in her place, orbiting the great man.

Celia Paul’s memoir, Self-Portrait, is a different animal altogether. Lucian Freud, whose muse and lover she was, is rendered here—and acutely—but as Paul puts it, with typical simplicity and clarity, “Lucian…is made part of my story rather than, as is usually the case, me being portrayed as part of his.” Her story is striking. It is not, as has been assumed, the tale of a muse who later became a painter, but an account of a painter who, for ten years of her early life, found herself mistaken for a muse, by a man who did that a lot. Her book is about many things besides Freud: her mother, her childhood, her sisters, her paintings. But she neither rejects her past with Freud nor rewrites it, placing present ideas and feelings alongside diary entries and letters she wrote as a young woman, a generous, vulnerable strategy that avoids the usual triumphalism of memoir. For Paul, the self is continuous (“I have always been, and I remain at nearly sixty, the same person I was as a teenager…. This simple realisation seems to me to be complex and profoundly liberating”), and equal weight is given to “the vividness of the past and the measured detachment of the present.” You sense both qualities in her first glimpse of Freud, in 1978:

His face was very white, with the texture of wax. It had an eerie glow as if it was lit from within, like a candle inside a turnip. His gestures were camp. He stood with one leg bent and his toes, in their expensive shoes, were pointed outwards. He sucked in his cheeks in a self-conscious way and opened his eyes wide until I looked at him, and then his pupils, which were hard points in his pale lizard-green irises, slid under his eyelids and I could only see the whites of his eyes.

In the head of the muse were the eyes of a painter. At the time, she was at her easel, watching Freud enter the basement life-drawing class at the Slade School of Fine Art, where he was a visiting tutor. He liked to make a dramatic entrance. In Paul’s case, it all happened with unseemly speed. In a moment he is beside her; she shows him some drawings she has done of her mother; a painting of her father. He touches her back, suggests they go for tea, and after that tea, they get in his car:

Advertisement

As we drove west the low autumn sun was blinding. He took my hair and wound it around his fingers and started stroking my throat with a soft rotating movement. I felt his knuckles on my throat through my hair. He stared at me fixedly and told me I looked so sad. He asked me for my phone number.

At his flat, more tea:

As I was drinking it, he came and stood behind me. He lifted up my hair and buried his face in it….

He pulled me gently but insistently into a standing position. I watched him kissing me and my mouth was unresponsive. I saw the whites of his eyes and he looked blind. His head felt very small and light as eggshell. I was frightened. I asked him what he thought of my work. He said that it was “like walking into a honey-pot.”

Talk about Freudian! Though I wonder if they’re thinking of the same honey-pot? For a muse, the sweet temptation is validation: you want to know what the great man thinks of your work, even if the great man wants something else first:

He started to kiss me again, but I was insistent that I had to go back now. I told him that I had arranged to meet up with a life model, who I hoped would be able to sit for me privately.

In museography, art and sex struggle with each other, intertwine, become finally indivisible. But when the muse happens also to be an artist, the struggle is existential, because to submit entirely to musedom, to being seen rather than seeing, would be to lose art itself:

As I was leaving I noticed a beautiful unfinished painting by him…. It was of a woman with her head resting on one side in a dreamy reverie. Her mouth was half-open. The image was full of love. When I was halfway down the stairs I heard him calling after me in a gentle voice, “Thanks awfully.”

Paul, young or old, does not scorn the idea that gratitude can exist between muse and artist, and move in two directions: love lessons becoming art lessons, and vice versa. But she does not romanticize the price of entry, and from the start knew to be cautious. Rather then meet Freud the following week, she avoids the Slade, preferring to stay at home, drawing. He starts calling. She agrees to meet him in Regent’s Park, where he spontaneously begins kissing her waist (“I felt very sad, also unnerved”). She meets him the following day, at his insistence. The moment she arrives at his door he presses her against the wall and starts kissing her again. In an attempt at “winsome prevarication,” she tries reciting Yeats’s “He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven,” but he “seemed rather irritated” by it and soon leads her to bed. “I felt that I had sinned and that something had been irreparably lost. I felt guilty and powerful. I felt that I’d stepped into a limitless and dangerous world.” She was eighteen. Freud was fifty-five. Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

So ends the section called “Lucian” that opens the book. It is directly followed by “Linda,” a chapter concerning the artist as a young girl, and within which Paul makes clear that it was her own childhood—rather than her encounter with Freud—that made her a painter. Inspired primarily by the Devon landscape in which she was raised—“I found objects on my walks through the woods and on the beach…and I arranged them to form still-lifes. I painted obsessively”—a little later she had a creatively significant “intense relationship” with a girl at her boarding school. Her name was Linda Brandon.1 Their relationship was nonsexual, urgently creative, extremely competitive, and centered around the art room of their school, to which both girls had been given a key by their art teacher. Each worked secretly, separately, late at night, inspired by envy of the work left behind by the other. Paul was “astonished” by Linda’s drawings, experiencing surges of jealousy so sickening “I thought I was going to pass out.” They match each other picture for picture, until, after one summer holiday, Paul comes back with a “huge amount of work,” while Linda has completed only one “half-finished drawing done in heavy black pencil of a dried sunflower head…. I sensed, with relief, that her passion for painting was beginning to fade.” Linda, vanquished—although still loved—takes up a place at a normal sixth-form college. Paul is put forward for the Slade. Lawrence Gowing, a professor there (and friend of Freud’s), took one look at her portfolio and immediately approved her application, even going so far as to write an encouraging letter to her “reluctant” father. (Including the memorable line “Pictures unpainted make the heart sick.”) If this chapter reads like a foundational myth of female “becoming,” ripped from the pages of Charlotte Brontë or Elena Ferrante, it’s no surprise. Girlhood seems to be one of the few periods of a woman’s life where her creativity can exist wholly without shame: unbound, feverish, selfish.

Advertisement

In adulthood, things change. Female creativity finds itself in conflict with traditional feminine responsibilities:

One of the main challenges I have faced as a woman artist is the conflict I feel about caring for someone, loving someone, yet remaining dedicated to my art in an undivided way….

It was a conflict of desire that I suffered at first with Lucian…. He spoke admiringly to me of Gwen John, who had stopped painting when she was most passionately involved with Rodin, so that she could give herself fully to the experience. I felt that there was a hidden reproach to me in his words.

Not so hidden.

There is a tension between seeing and being seen. When the young Celia Paul first sits for Freud, she is “very self-conscious, and the positions I assumed for him were awkward and uncharacteristic of the way I usually lay down. I was never naked normally.” She ends up covering her face with one hand and cupping one breast with the other. (“‘That’s it!’ he said. I knew that it was the way the skin of my breast rumpled under the touch of my hand that had attracted him.”) It’s when he paints her breasts that she’s most aware of taking on the role of object: “I felt his scrutiny intensify. I felt exposed and hated the feeling. I cried throughout these sessions.” The painting is Naked Girl with Egg, because Paul’s breasts reminded Freud of eggs. He also painted two actual eggs in the foreground of the picture—in case, perhaps, the connection was obscure. One effect of the eggs is to emphasize how much the flesh looks like meat beside them, and the material under Paul like a tablecloth, as if she herself is part of the meal.

By contrast, when it’s Paul’s turn to do the seeing, consciousness of objectification and its consequences became part of her process. Her first satisfying life-drawing experience is with an Italian model called Lucia, with whom she feels a special connection, because, “unlike the other life models who never showed their feelings,” Lucia weeps, and describes feeling degraded by the filthy mattress at the Slade, by the students who never speak to her. Paul began to develop a different understanding of what it means to see and be seen:

I couldn’t understand the principle of life drawing. It seemed so artificial to me to draw a person one didn’t know or have any involvement with…. I needed to work from someone who mattered to me. The person who mattered most to me was my mother.

Throughout her career, Paul has painted only people and places she knows well: her son, her four sisters, her father, and especially her mother, over and over again, using her own emotional relation to them as an aesthetic principle: the portraits “were necessary because I loved [my mother]. Their necessity gave them their force.” In her view, “the act of sitting is not a passive one,” and can be noticeably different for women and men:

I have noticed that the men I have worked from are interested in the process of painting and in the act of sitting. The silence, when I am working from men, is less interior. Women, in my experience, find it easier to sit still and think their own thoughts, and they often hardly seem to be aware that I’m there in the same room. For this reason I usually feel more peaceful when I’m working from a woman, and more free.

In the case of her mother, who was religious (Paul’s father was a bishop), this stillness had the added dimension of faith, for she was often silently praying during the many hours she sat for her daughter:

She entered into the silence with her soul. Her face assumed a rapt expression. My painting was raised to a higher level, too, because of her elevated state. The air was charged with prayer. She was always ecstatic if she felt she had sat well.

With his own sitters, Freud liked to talk and be listened to. Paul records some of this conversation in a letter she wrote home: “He said much more, like how the Greek sun seems to preserve the colour in cloth and furniture so that a regency chair is startling but that women start to go downhill at an avalanche pace from the age of sixteen etc. etc.”

Freud painted the visible: flesh, breasts, eggs. Paul’s work is a visionary account of ineffable qualities, like love, faith, silence, empathy. All of which can be made out in what she calls her “first real painting,” Family Group (1980; see illustration above). Gowing called it the best painting done by a Slade student. Freud admired it, too, as Paul does not omit to mention:

He said, “I’m thinking of your painting.” He started to think about doing a big painting involving several sitters, and he ordered his biggest canvas yet to be stretched…. On this canvas he was to conjure up “Interior W11: After Watteau.”

One of the subtle methods of this crafty book is insinuation, creating new feminist genealogies and hierarchies by implication. Is Interior W11, for which Paul posed, after Watteau—or after Paul? There are the similarities in the composition: the resting hand, the averted eyes, the cramped space, and the rectangular escape-hatch—for Paul a mirror, for Freud a door, but in both cases opening onto a different view, like a release valve from the intensity of family life. But to imply a mutual influence between these painters is also to highlight the differences in approach. In Paul’s painting, wavelike brushstrokes surround the family and seem to connect them, like auras, radiating most intensely around their heads, as if the mental conception of familial love were a sacred substance itself, that paint might render visible. (Paul is present in the mirror’s reflection, thin and spectral, a benign spirit watching over her clan.) “The whole composition,” Paul writes, “is lit with an inward glow.”

In Freud’s painting, Paul—the new lover, at far left—must contend with her lover’s children and step-children, as well as the ex-lover, Suzy Boyt, who had four children with Freud after also meeting him at the Slade, twenty-five years before Paul. This improvised family group sits together in a room of little warmth—rusting pipes, peeling paintwork, half-rotten greenery—against which they are each sharply outlined, like anatomical examples of their kind. Under their skin, Freud uncovers his familiar butcher-shop pinks, his blues and grays—suggestive of veins, arteries, and organs—which are then echoed in the meaty shades of the exposed walls, and likewise make the case for inevitable decay.

“The forms grew bigger as he progressed,” writes Paul of the construction of Freud’s painting,

so that we appear to be squashing up next to each other. Despite the physical proximity, each figure seems locked into her or his private world and there is no emotional empathy between us. We look lost and isolated, like sheep huddled together in a storm.

The storm, of course, was Freud himself, father of fourteen acknowledged children with six women. Traditionally, museography has considered critiques of such arrangements tediously puritan. (Although, by the time Freud died, in 2011, a grudging shift was taking place. You can hear it in some of the posthumous profiles: “As raffishly bohemian as these arrangements may sound, it was no easy road for the women and children involved.”) Interior W11 aestheticizes the complex family romance Freud liked to cultivate around himself. (He seemed to require, Paul delicately suggests, an “undercurrent of jealousy…as a stimulus to his own affairs.”) It’s less a group portrait than a staged drama about power, depicting five atomized people tethered to a central figure not pictured. They are all there for Lucian, only for him. Of course, this is true of all portraits—the sitters always appear at the artist’s bidding—but few painters have put as much emphasis on sitting-as-subjection. (The youngest child looks less like a child reclining than a rag doll, destined to remain wherever you drop her.)

A year into their relationship, Paul discovered that Freud had several young lovers at the Slade. Devastated, she cautiously expressed her pain to Gowing, he of the kind letter about unpainted paintings. But by now, Celia was a muse, so a different kind of advice was in order: “He says that he has known Lucian since he was sixteen and knows that he just doesn’t commit himself to one single person—not through unconcern but just because this was the stony cold mode of living that his art flourished on.” Paul records her subsequent suicide attempt with surreal British restraint, in five sentences, never to be mentioned again:

Everyone at The Slade was gossiping about Lucian, and they delighted in telling me about all the people he was having affairs with. I became severely depressed. One night I swallowed a packet of Veganin [a painkiller], washed down by a bottle of whiskey. This landed me in hospital. I went home to recover.

After this she remains with him. Anyone who has ever waited for a text or an e-mail from a lover—but never known the pain of the landline or the postal service—will marvel at the old ways, when a woman could find herself constrained to the house for days, awaiting a sign. And he remains promiscuous. Sometimes he gaslights her about it (“You’re crazy”). Sometimes he defends it (“It doesn’t alter what I feel for you”). Sometimes he claims the bohemian’s license (“I don’t know if it’s right and I don’t know if it’s wrong”). Sometimes he forgets what he said before and has to adapt:

“You lied to me.”

“When did I actually lie to you?” He is very gentle to me.

“When I asked you if you were going with anyone else you said—of course not.”

“Oh yes,” he murmurs. “You know I almost always tell you the truth.”

Sometimes her teenage diary displays the same cool insight that distinguishes Self-Portrait as a whole: “He does not love me.” More often, she proved a child at sea, caught in the eye of Storm Freud:

His mood is brittle gentleness. I say one careless foolish word and he flings a hundred back at me, so angrily, so full of hatred, and then the ice-cold kindness seals the crack again and I am left feeling completely humiliated. Soon I lose my voice, my thoughts are covered in mist.

When the mist clears, it turns out that aside from the many girls, there is also one particular, special girl, whose name Paul finds in his open diary. At this point, the reader is wont to judge harshly, while the museologist will argue that those were different times. They certainly were:

I go to The Slade. A tank of tropical fish is on the table in the space next to mine and my friend is painting diluted watery shapes…. I think she doesn’t look too absorbed in her work so I tell her all about my jealous suspicions.

She says, “Would you like some heroin?”

But after this little pick-me-up—“I feel the emptiness and misery desert me and instead I am completely at peace and full of love for everybody”—Paul, walking through Soho, bumps into the named girl, who confirms the affair and the fact that, as far as teenage hearts are concerned, some things never change: “It’s as though she held all my life, my trust, my self-respect, like a little glass paperweight in her hand which she now let fall, and only I perceive the tragedy of the shattered fragments.”

Broken? Not really, never entirely. If male artists sometimes stage dramas of power, it is not unknown for female artists to make a performance of masochism. Neither performance should be entirely trusted:

Always when you turn to go

There is grace in your turning

So that I would call you back

But I know

That it is the coldness of your going I crave

And not your returning.

So run some lines of Paul’s teenage poetry, and they offer a hint of the uses of masochism, as creative prompt, as inspiration. Real masochism would surely mean unpainted paintings, unwritten poems. Whereas Paul’s work gets done, through everything, as if to prove that classically feminine principle enshrined in the ideology of the housewife: of “making do,” through pain, through lack, using whatever is to hand, which, in Paul’s case, was usually her own mother:

I read a story about St Brigid in a book of women saints that I had. St Brigid had performed the miracle of giving a blind woman her sight for a split-second. The blind woman had seen fields with cattle grazing in them. The scene was so beautiful to her that she said the split second was all she needed, and that the memory of it would light up her life for evermore.

Paul will go on to use this sanctified tale of female masochism as potent inspiration to envision her mother as Saint Brigid, with the Yorkshire Moors behind her, cattle grazing in the distance. She’s painted lying down, apparently deep in meditation or sleep, unaware of an observer, with one hand flat on her chest and the other resting naturally in her lap, as a real woman might unself-consciously position herself. Freud said once that Paul’s people resemble landscapes, and so it is here: her mother’s olive-green sweater melds with the moors; her face, even with eyes closed, looks mobile and stormy, like weather. (“My mother is dreaming up her own protective world.”) She seems not a person so much as a first cause, being the foundation of, and reason for, Paul’s own existence. (And isn’t this, for better or worse, how we think of our mothers?)

When Paul was twenty-five, she gave birth to Frank, her son by Freud. Motherhood is the perfect stage on which to perform feminine masochism, but as many new mothers have discovered, it can also be the occasion to confront one’s inner Saint Brigid once and for all. Of the many wonderful images in this book, the one I kept returning to isn’t a painting at all but a photo of mother and child, beaming at each other, locked in intense, joyful relation. (Lucian was nervous about holding Frank, “found it difficult to deal with the fact that I was preoccupied and not so readily available after the birth,” and, despite already having fathered many children, still appeared confused by the process of raising them: he “was disturbed by the milk that had leaked onto my dress: ‘What’s that?’ he asked. I sensed that it repelled him.”) So intense are the joys that Paul experiences her love for her son as a kind of self-submerging, as she notes in her diary, directly after his birth:

I would like to give up everything for him. I would like to be swept away and lost in this powerful tide of maternal love. I would like all my ambition and all my desires to be drowned with me.

But some contrary instinct is working in me at the same time: I must save myself too.

Saving herself—for art, for love—requires “rearrang[ing] the structure” of her life. In order for Paul to continue working, from the time he is three weeks old her son’s “main carer” becomes his mother’s mother, which Paul frames as a defense against artistic erasure: “When I am with Frank I don’t have any thoughts for myself. All my concerns are for him. Therefore I am unable to work when he stays with me.” (This instinct for self-preservation remains: even now, she lives separately from her beloved husband, the poet and philosopher Steven Kupfer, who has no key to her apartment.) She also needed time to continue loving Lucian, and sitting for him, though she senses both roles are different now: “Something in me had changed. I felt more powerful and confident since becoming a mother. I was beginning to have more of a sense of who I was.”

What is so spooky about Freud’s Girl in a Striped Nightshirt (Paul’s sitting for which extended through pregnancy and birth) is that this tremendous shift in her personhood goes unregistered. Still the meek girl-child; still the downturned eyes. Freud had spoken to Paul at that time of “Rodin’s hurt when he no longer had complete control over his lover, Camille Claudel. Lucian said that he understood how painful that feeling is.” Girl in a Striped Nightshirt is a very tender painting, wistful for the continuance of a quality that has already transformed, that perhaps was never there in the first place.

The painting that does try to recognize the end of Paul’s musedom is his Painter and Model (1986–1987), begun a few months later, notably after Paul’s first successful solo show. (Saatchi bought, among other works, My Mother as St Brigid, Dreaming.) In it, Paul is presented as a painter, standing up with brush in hand, fully clothed except for her bare feet, her dress covered in paint. A naked, open-legged male friend reclines on a sofa beside her, limp penis front and center. Paul’s face has lost all its feminine softness, her nose is sharp, her brush is extended, the man is exposed and vulnerable. Paul’s toes look strangely forceful and are crushing a tube of paint on the floor. Paul at once understood the nature of this double-sided tribute, and is honest about her own ambivalent reaction:

I felt honoured that Lucian should represent me in the powerful position of the artist: his recognition was deeply significant to me. But underlying my pride, I felt wistful that I was no longer represented as the object of desire.

Soon after, she found herself supplanted by a new muse: “Without my being aware of it, she was seen by most people as the main person in his life. I had been displaced. In February 1988 I decided to split up with him.”

Finishing this powerful little book, I was prompted into an embarrassing recollection: as a teenager, I tried to write to Freud, to offer myself up as a model. I’d seen his painting of the fleshy woman from the Department of Social Security, and being pretty fleshy myself at the time, I thought he might appreciate me as a subject—validate me as a subject, I suppose is what I mean. (I wrote a similar note to Robert Crumb.) I remember writing that letter but don’t recall sending it. Still, the role of muse-masochist was clearly in my repertoire, as it is in the repertoires of so many young girls. This Freud knew well.

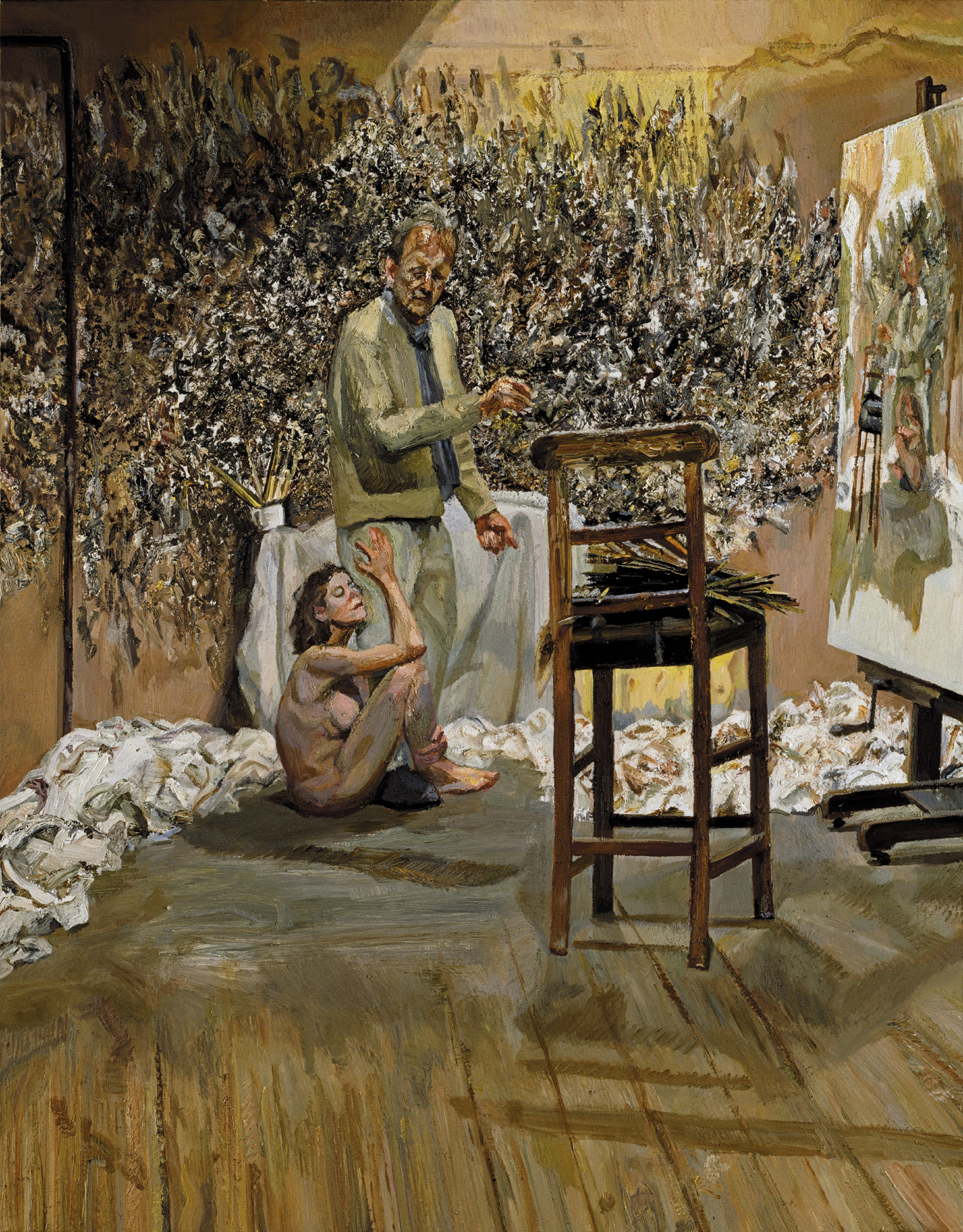

One of the most startling evocations of the muse-masochist is by Freud: The Painter Surprised by a Naked Admirer (2004–2005).2 The girl in the painting is Alexi Williams-Wynn. She was thirty-three years old—relatively old for Freud, but then, he was eighty-three at the time. She sat for him “seven days a week, night and day,” convenient in its way because of course they were also lovers. By that late stage in Lucian’s life, an affair no longer outlasted a sitting (perhaps for reasons of economy, given his age), and after the two paintings he did of her were finished, so was the relationship. Still, being a muse means endeavoring always to see the bigger picture—even through heartbreak—and so it was with Williams-Wynn, for whom the experience perfectly illustrated the ideology that created it: “Being with Lucian made me realize that this is no joke: being an artist, being alive. It also made me understand that selfishness is what it takes to make great art.”

It’s what many of Freud’s children believed—or had to believe—in order to accept the sort of familial relationships mostly conducted through portrait sittings. And it’s what all we students of twentieth-century museography took as our creed. But is it true? Celia Paul is, in my view, also a great artist and a selfish one—by her own reckoning. Selfish with her space and her time, with her need for quietude. But are selfishness and exploitation quite the same thing? Paul’s selfishness seems more a defense against obliteration than anything else. Still, isn’t choosing to give up primary care of a child also a “stony cold mode of living”? And that, the museologist will argue, is exactly what makes a great artist!

This debate is usually posed in the banal form of an either/or. As in: Can I still love X great artist given that he or she behaved in Y way? Or must I shun them? In the case of misogyny, this mode of argument may miss the point. Lucian Freud’s art, whatever its merits, contains within itself the fundamental limitation of misogyny, which is a form of partial sight, a handicap with precise consequences if you happen to be a portraitist whose subjects were often women. For example, the Celia Paul whom Freud believed he saw, whom he set out to paint—that pretty, mild girl with her eyes downcast, “meekly ‘there,’ for him to do whatever he wanted with me”—was not really the person lying before him. This is not to claim that Freud’s portraits of Paul are either “wrong” (whatever such a word could mean in this context) or even bad, but simply that they are notably partial, being blind to so much, indeed, to the essential quality of the subject in question. Freud thought he saw it all, purely, clearly, without distortion—that was his fame.

But, when it came to women, he did not see. Misogyny, whatever else it might be, is a form of distortion, a way of not seeing, of assuming both too much and too little. It was beneath—or beyond—his notice to capture that the pretty, apparently passive body lying naked before him thrummed with painterly ambition, just like his, and intended to save itself for the purposes of art, just as he did. And even when Freud realized, belatedly, that Paul was a painter (rather than a muse or a mere art student), he was blind to the idea that this person, the “woman painter,” might still be a whole human, capable of erotic passion, just like himself, and not a fake man, with a set of violently phallic toes. (Perhaps to demonstrate this, Paul shocked Freud, two months into new motherhood, by having an affair with an eighteen-year-old student she met on a train.) Many years later, after Freud died, Paul painted her own Painter and Model (2012), in which she need make no choices between being a woman and an artist:“I have it all. I am both artist and sitter. By looking at myself I don’t need to stage a drama about power; I am empowered by the very fact that I am representing myself as I am: a painter.”

There was, when Paul began painting, very little in the way of theoretical support for her way of seeing (or paternal support for the raising of children). And she made her life professionally difficult in other ways. Impractically, she has never conflated painterly ambition with size of canvas. And her “attraction to the juxtaposition of the mystical with direct observation” is, as she herself points out, the opposite of Freud, who rarely worked from his imagination and believed in painting exactly what you saw in front of you. Freud was oblivious to those ulterior channels that Paul senses exist between people, above and beyond mere sight. And this emphasis on the ineffable has meant, among other things, that Paul was never called upon to paint, as Freud was, Kate Moss or the queen, or even Jerry Hall, all of whom seem limited as subjects of mystical inquiry. Paul’s canvases do not aim at unvarnished verisimilitude. She has no interest in remaining, like Freud, clinically unfazed in the face of vanity and power. She has no interest in vanity or power as subjects. Freud saw veins, muscles, and flesh where the rest of us tend, sentimentally, to see a human being. But people are not only their bodies.

After her mother died—and Paul and her sisters fell into deep mourning—Paul asked a niece to make all her sisters identical white dresses from old sheets. With her sisters thus begowned, Paul painted them sitting in a half-circle, like figures from some aristocratic realm of the spirit, female bearers of a spiritual expertise that rarely gets seriously considered, never mind painted:

I needed them to sit for me all together because of the supernatural empathy that ran like an invisible skein between them. The silence was powerful and charged with spirit, almost as if we were in a seance, conjuring up the spirits of the dead.

That “invisible skein” between people—this is Paul’s improbable subject, and she sees it exquisitely. But, as with every artist, there are things Paul does not see. She has no sense of the absurd, and no feel for the humor that can arise from acid first impressions. She cannot use paint to deflate pomposity, or ridicule the false auras that surround money or power, as Freud achieved so delightfully in his portraits of the British upper class. She has none of his witty cruelty, in short, which is a painterly attitude perhaps only possible when you don’t love your subjects or even know them—when everybody’s mere flesh to you, even the queen of England.

Paul’s blind spot might be power itself. Yet we should, I think, be careful how hard we bear down on blind spots, seeing as how every artist has them and any artist can fail to see such a myriad of things in this world: men, women, children, nature, animals, class, race, power, love, cruelty, and so on. It should be possible to identify and critique partial visions without putting out both our eyes. But the unusual thing about misogyny is the elaborate intellectual superstructure that has for so long supported and celebrated it, not as blind spot or as pernicious ideology but, on the contrary, as perfect vision. What else will we start to see now the mist of misogyny begins to clear?

Self-Portrait will go some way to clearing that mist from the world of portraiture, and might also act as gentle intervention, intended for the kind of young girl tempted to swap self-realization for external validation. I don’t suppose that muses will ever disappear, but perhaps now they will less regularly take that wearying, inadvertently comic form: old man, young girl. Or always have sex at their center. And perhaps if more women artists during the twentieth century had been as storied, as celebrated, as Lucian Freud, we might all know a lot more about the many musedoms that exist beyond that naked girl: the inspiration of one’s mother, one’s child, one’s siblings, one’s life partner, one’s oldest friends.

This Issue

November 21, 2019

The Defeat of General Mattis

Lessons in Survival

-

1

The nonchronological location of this “Linda” chapter—which would place a man’s effect on a woman above her own formative experiences—is interesting, and perhaps related to the effects of musedom on the editorial departments of publishing houses. ↩

-

2

One way to interrogate such images is to invert them: to imagine the venerable, octogenarian lady-painter with a gorgeous, naked, male art student clinging besottedly to her thigh—and then try not to smile. ↩