A biography of Dario Fo and his wife, Franca Rame, is inevitably a history of Italy in their lifetimes and particularly in the decades from 1950 to 1990, when their careers as playwrights, actors, and political activists were at their peak. Play by play, show by show, Fo engaged in fierce polemics with more or less every aspect of Italian society. His work, as Joseph Farrell observes in Dario Fo and Franca Rame: Theatre, Politics, Life, contains none of the intimacy, intellectual cogitation, or existential angst that one finds in so many artists of the twentieth century. Nor can his excellent biographer find much of it in the life. All Fo’s energies were invested in the theater, or in the clash for which the theater, and occasionally television, were his chosen instruments.

Once drawn into the influence of this brilliant comet, Rame became one with it, no doubt altering its trajectory and intensifying its light, but not changing its essential nature. For a biography of a couple there is remarkably little that touches on their private world together—perhaps because there was no private world. Their life simply was this bright, festive, cruel light they shone on Italian society. And whatever one thinks about the aesthetic value of this or that play, their endeavors always had the virtue of forcing all sides to come out in the open and declare themselves. As a consequence, Farrell’s book is one of the best introductions to postwar Italy I have come across.

Fo was born in 1926 in a village near Lake Maggiore, fifty miles northwest of Milan. His father was a stationmaster, his mother of peasant stock. The eldest of three children, he enlisted his younger brother and sister as audience and supporting actors in home theatricals and puppet shows. From the first, Dario was prime mover, energizer, and star. At age fourteen, his promise was such that his parents sent him to Milan, where he attended the Brera Liceo, a school attached to the city’s foremost art college.

At seventeen, this cheerful adolescent received call-up papers to join the army of the Italian Social Republic, the northern Italian state that Mussolini had formed with Nazi support after the Allied invasion of Italy from the south in 1943. Fo’s parents were antifascists. Other young men fled to the mountains to join the partisan resistance. Fo, however, as he later said, “preferred to choose a waiting position and try to dodge the call-up with trickery.” Eventually he volunteered for a unit he hoped would not be engaged in fighting. He deserted, reenlisted, and deserted again, hoping “to hide away, to come home with my skin intact.” It was an uncertain start to an adult life that would later be marked by a willingness to assume radically antiauthoritarian positions in the face of aggressive harassment. Perhaps the difference in 1944 was that Fo didn’t perceive the battle as his own; he was merely a pawn. “In the unpromising surroundings of his barracks,” Farrell remarks, “Dario managed to perform some comic monologues.”

Between 1945 and 1950, while studying painting and architecture in Milan, Fo was gradually drawn toward the theater. On the train to Lake Maggiore and back, he would entertain other passengers with comic performances mocking the status quo. A “Puckish mischief-maker,” as Farrell describes him, he invented all kinds of practical jokes, on one occasion selling tickets to a supposed reception for Picasso in Milan, then producing a janitor from Brera who had some resemblance to the artist. He began attending plays directed by the socialist Giorgio Strehler at the newly opened Piccolo Teatro. He read Gramsci’s books, which encouraged the rediscovery and reevaluation of popular culture as a necessary step on the road to a Marxist revolution. In 1950 he asked Franco Parenti, a successful theater and radio actor, to listen to his monologues. Parenti was impressed, and later that year the twenty-four-year-old Fo signed a contract with RAI (Italian Public Broadcasting) to produce twelve solo shows. His career had begun.

Despite its uneven quality, there is a remarkable consistency to Fo’s work over the years, and to the turbulence that invariably develops around it. It begins with an act of appropriation and inversion. A well-known story—Cain and Abel, David and Goliath, Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Christopher Columbus, Rigoletto—is taken and turned upside down; we sympathize with Cain, with Goliath, with Juliet’s parents; the “official” version of history is perverse and serves a ruling elite. Fo collected his early monologues under the title Poer nano—literally “poor dwarf,” but with the colloquial meaning “poor sod,” “poor loser.” The world’s injustices are seen from the point of view of the victim, but the sparkling comedy that Fo injected into his performances transforms this loser into a winner.

Advertisement

RAI suspected a political agenda and broke off the relationship. It was an outcome Fo would grow used to. In one monologue, based on the Rigoletto story, he played a jester who, as Farrell puts it, “faces the dilemma of being either court entertainer, and hence the plaything of authority, or the voice of the people.” It was Fo’s own quandary. RAI wanted light entertainment. Fo resisted. Very likely the pressure to keep politics out of his work led to his becoming more “the voice of the people” than he originally planned. The tension was fruitful.

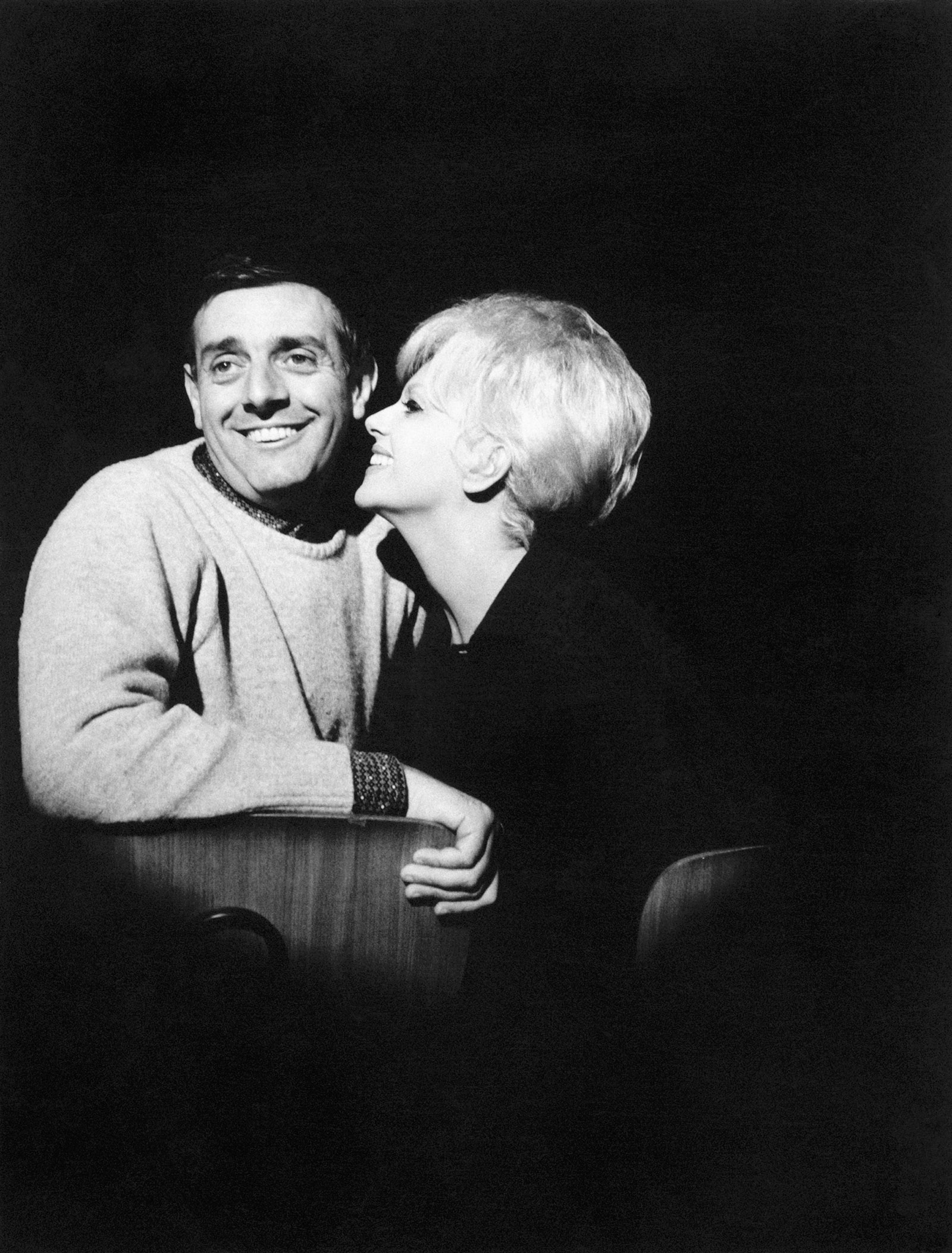

Without the radio work, he fell back on cabaret and variety, and in 1951 he found himself in the same show as the blond, glamorous, wonderfully lively Franca Rame. She was three years younger than him and came from a family of traveling actors who could trace back their involvement in popular theater for hundreds of years. Essentially, the Rames wrote the outlines of their stories, often borrowing them from existing plays and novels, then improvised onstage in the Italian tradition of commedia dell’arte. It was theater without the authorial figures of writer and director, and as such emblematic of the popular culture that Gramsci had sought to champion. Fo was fascinated.

But he did not court Franca. “His grin was toothy,” Farrell says, “his nose jutted out like a small promontory, his arms dangled, his legs were seemingly out of proportion to his trunk and his gait was gangling and tumbling.” In short, Dario was no Adonis, and Franca, he later remembered, “was always pursued by hosts of men prepared to go to any lengths. I didn’t want to enter the lists.” Eventually, Franca took the initiative and kissed Dario backstage. All too soon the couple had to borrow money for an illegal abortion. Then the “gorgeous bitch,” as Dario described her, left him. Dario had to wait until they were working together in his first show “to win her back.” In 1954 the two married, Farrell writes, “to please her devoutly Catholic mother,” and in 1955 Franca gave birth to their only child, Jacopo.

Fo never went to drama school and had no formal training as an actor or director. Nor did he have any ambition to have his plays published as literary works. What mattered was the moment of performance, when he was triumphant, and often triumphantly himself, as storyteller rather than character actor. The problem throughout his career would be to create a form of theater that suited his talents and made sense in the rapidly changing sociopolitical circumstances in which he moved. Crucially, in the two shows he put on with Parenti at the Piccolo Teatro in the 1950s, A Poke in the Eye and Madhouse for the Sane, Fo was able to draw on the stagecraft of Strehler and take lessons with the mime expert Jacques Lecoq, who also helped him, according to Farrell, to “acquire that range of laughs and onomatopoeic vocalisations which were indispensable to his monologues and enabled him to reproduce everything from storms at sea to tigers licking wounds.”

In the theater as on the radio, debunking conventional viewpoints in a carnival atmosphere proved at once popular and controversial. On tour, his shows met resistance from church and local authorities. The script of Madhouse for the Sane, Farrell writes, “was massacred by the censors” working under the direct supervision of the future prime minister Giulio Andreotti, then an undersecretary of state. Fo chose to ignore the changes they demanded and got away with it.

Alongside these invigorating battles with the conservative establishment, there were also disagreements with collaborators. Strehler was a champion of Brecht; Fo found his approach too complacent in positing a savvy middle-class audience. Parenti was an admirer of French absurdism, of Ionesco and Beckett; Fo found these writers too intellectual and abstract. He wanted a more direct, seductive relationship with his audience. He did not want to be trapped in a rigid script.

In 1956 he and Franca went to Rome and made a film, Lo svitato (The Screwball), reminiscent of Jacques Tati. It flopped, an experience far worse than getting fired for being provocatively popular. “Years later,” Farrell observes, “he could repeat audience figures in various cinemas in Rome, recite box office takings in an experimental cinema in Milan.” He had failed, Fo felt, because actors were powerless in the cinema. He had lost control of the product. It must never happen again.

He and Franca returned to Milan, set up their own theater company, and produced a string of slapstick farces complete with song and dance. These were the years of the postwar boom, a general economic optimism coupled with touchy Catholic conservatism. Fo was seen as “a scoffing but jovial bohemian rather than…an enraged iconoclast.” This beguiling image was reinforced when the couple agreed to take over the TV program Carosello, ten minutes of short sketches, each advertising a different product or brand. Still available on YouTube, these hilarious pieces show a charmingly goofy Fo playing dumb beside the voluptuous Franca, the punchline of each two-minute routine producing a well-known brand name like a rabbit from a hat. With only one state-run channel, Italian television was so tediously predictable that Carosello became the most popular program.

Advertisement

In Milan too the couple’s complementary charisma was outselling every other Italian theater of the time. The titles of their shows—Thieves Mannequins and Naked Women, Bodies in the Post and Women in the Nude—invited audiences to expect risqué material; light comedy was mixed with political protest, against the church’s stranglehold on public mores, corruption in the building industry, or bourgeois hypocrisy. Stock figures appeared: the faux-naif who shows up society’s sham, the prostitute with the golden heart, the madman as the only sane person in a crazy world. Fo was always the lead actor, Franca always the leading lady, ever ready to appear in a negligée to keep audiences happy. Did the plays amount to literature, asked the theater magazine Sipario, when it published the script of Archangels Don’t Play Pinball? The “best” of the play, it decided, existed only onstage in “the bare-knuckled struggle in which Dario Fo the actor and Dario Fo the author engage…to gain the upper hand.” Fo was competing with Fo. He needed stiffer opposition.

He found it in 1962. Invited to take over RAI’s hugely successful TV variety show Canzonissima, Fo injected some sharp political satire into a routine of “high-kicking, scantily clad, sequinned dancing girls,” ridiculing the complacency surrounding Italy’s economic miracle and the fawning subservience of the white-collar classes. In one sketch, a demented employee caresses and worships the statue of his boss. Typically, the more successful the program became, the more opposition Fo encountered. Finally, a sketch showing a construction magnate refusing to spend money on safety measures, then taking his mistress to buy expensive jewelry, was banned. Fo and Rame walked out. They would not be allowed back on national television for fourteen years. But their name was made, and Fo, who thrived on antagonism, had understood that controversy and celebrity could be one and the same thing.

In the mid-1960s the Italian economy took a dive while a growing permissiveness drew audiences to plays that were openly provocative. Social conflict took on a new edge. Back in the theater, Fo found ways of dramatizing the kind of tension he had experienced at RAI and taunting his audiences. One play ends with a chorus of asylum inmates, whose brains have been surgically altered to make them acquiescent, singing, “We are happy, we are content with the brain we have.”

But box-office success now made Fo wonder if the pleasures of his clowning and Franca’s witty glamour weren’t making the shows too anodyne. Seeing a fur-coated lady entirely happy with her night out made him anxious. Again and again, Farrell’s biography describes Fo wrestling with the question of how to combine the enjoyment theater must afford with the arousal of a socially transformative anger that would make it relevant and important. He thirsted for bigger battles, more radical victories. He visited Communist Eastern Europe, Cuba, declared himself a Marxist. He ransacked history for accounts of social conflict that could be dramatized as analogous to contemporary life. Catharsis was condemned as a bourgeois trick that reconciled the spectator to injustice.

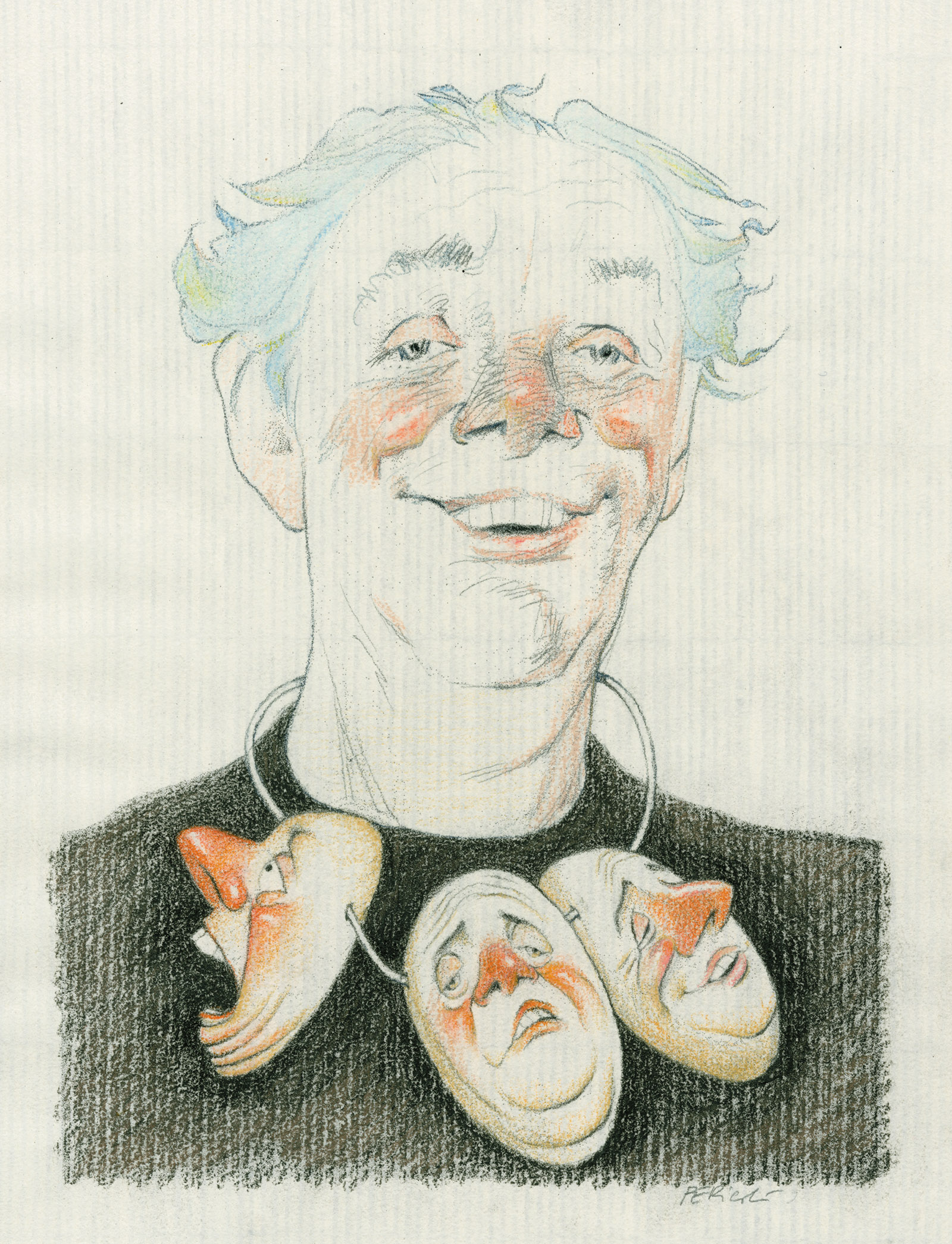

Most of all, he began to see himself as a man with a mission, in the tradition of the giullare, the jester or court fool who invents stories that speak truth to power and galvanize the populace. He would spend much time over the coming years researching and to a degree falsifying this historic figure, in an attempt to give dignity to the special position he was creating for himself. When social unrest exploded across Europe in 1968, Fo and Rame abandoned the conventional theater circuit and set up an actors’ cooperative, Nuova Scena, which would play in Communist Party clubs around the country, returning theater to its popular origins and putting their talents “at the service of the revolutionary forces.”

Farrell’s account of this endeavor points up its fertile contradictions. Fo and the increasingly politicized Rame insisted that Nuova Scena would be egalitarian; everyone would have a say, everyone would be paid the same. Yet there was an abyss between their talent and that of the young, left-wing intellectuals their venture attracted. Resentment against capitalism could quickly morph into bitterness toward Fo and Rame for staying in expensive hotels, hogging the limelight, and cashing their royalty checks, which did not form part of the equal payroll package. On the other hand, audiences wanted Dario and Franca, not the others. Farrell reports energy-sapping discussions “conducted in a sub-Marxist jargon…as impenetrable as the disputations of medieval monks.”

Just as Fo had offended RAI when he worked for them, now he offended the Communist Party on which he depended for his venues. Seizing on issues of the day and putting them directly to his audience, he drew parallels between the American presence in Vietnam and the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, while one play showed the Communist mayor of Bologna waltzing with the city’s cardinal. The Communist paper L’Unità accused Fo of “errors of evaluation and perspective.” Some venues no longer wanted him. Meanwhile, Nuova Scena played to 240,000 people across Italy, 90 percent of whom had never been to a theater before. Each performance was followed by a debate with the audience that could go on late into the night. It was exhausting.

In 1969 Fo launched the Mistero buffo—funny or buffoonish mystery—monologues and at last achieved the leap of quality that would lay the basis for his Nobel Prize in 1997. In his search for new material and popular rather than elite forms of theater, he had become fascinated by the Middle Ages and in particular the tradition of Christian mystery plays and apocryphal stories of Christ’s life. Many of these had been reworked by Renaissance artists, in particular the actor-playwright Angelo Beolco, better known as Ruzzante, who had become Fo’s idol and designated precursor. Appropriating, translating, and rewriting, Fo worked these stories up into a cycle of monologues that could go on for many hours.

The performance began with his addressing the audience directly to denounce the scandalous suppression of this more lively version of the Christian story, together with the figure of the giullare—the jester—who had once told that story. The authorities, he claimed, obstructed popular creativity because it undermined their power. He then gave an outline of the stories, drawing provocative parallels with issues of the day. All this was in standard Italian. The audience now primed, Fo transformed himself into the jester figure, launching into the monologue itself in a demotic onomatopoeic gibberish, or grammelot, that mixed various northern Italian dialects, Latin and French, archaisms, neologisms, and acoustic effects of every kind. For Italians brought up speaking both dialect and standard Italian—the norm in the 1960s—there was at once a powerful feeling of recognition and intimacy, and the impression of being shifted into some carnival space in a distant past.

Incantatory and often glitteringly incomprehensible, this torrent of strange language was clarified by the most energetic miming as Fo acted out all the parts in his story in an irresistible tour de force. A gravedigger sells seats to people eager to see Jesus raise Lazarus from the dead. A woman whose baby has been killed by Herod’s soldiers believes it has been transformed into a lamb. The boy Jesus tries to make friends by showing off a few miracles, then turns a rich bully to terracotta. A drunkard rejoices in the quality of wine at the Marriage at Cana. The execrable Pope Boniface dresses in all his finery but is shocked when he meets Jesus in rags carrying his cross to Calvary.

Mistero buffo is a rich and flexible package, the perfect vehicle for Fo’s exuberant genius. Crucially, while attacking injustice and a corrupt church, the stories leave respect for the Christian story intact. In this regard they might even be seen as tame and conservative, though that was not how they were perceived at the time, as audiences flocked to watch Fo at the top of his game and in total control of what was now exciting, meticulously prepared material.

Can Mistero buffo be performed without Fo’s special charisma? Can it be translated? In October 2019 Mario Pirovano presented the monologues in a fiftieth-anniversary production in Milan. Pirovano spent a long time living with Fo and Rame, learned to imitate him, and even to a degree looks like him. He has the mime, the dialect, and the grammelot down to a T. But one only need see a video of Fo’s versions to appreciate how much more dazzling his performances were, how aggressive the political commentary he worked into his introductions. English translations of the pieces preserve no trace of the linguistic wealth of the original.

Nineteen sixty-nine was also the year that left-wing terrorism began in earnest. Advocates of revolution rather than reform, Fo and Rame condemned the violence but became objects of intense police surveillance, particularly after Rame formed Red Aid, an organization that offered support to imprisoned terrorism suspects. Nuova Scena was shut down and the company Comune formed, to act out parables of political strife in factories and workers’ clubs up and down the country. Typically, Fo insisted that the company bring all the technical paraphernalia of theater—scenery, costumes, and lighting—despite the improvised nature of the venues. It had to be a seductive, professional show. Almost at once Comune was beset by the same internal quarrels that had dogged Nuova Scena, and it disbanded in 1973. In 1970, however, the company did produce Accidental Death of an Anarchist, Fo’s most successful straight play.

In December 1969 a bomb in a Milan bank killed seventeen people. The police arrested the anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli, who died three nights later in a fall from the window of the police station. It soon emerged that Pinelli had had nothing to do with the bomb. In Fo’s play a mad impostor (obviously Fo) convinces the dumb Milan policemen that he is an inspector from Rome who has come to help create some credible account of the anarchist’s death. In scenes as bitter as they are wacky, Pinelli’s interrogation is enacted over and over. Since court hearings on the death were proceeding as the play premiered, Fo changed the script almost daily to include material from the trial, much of it as grotesque and surreal as his original imaginings. The play led to forty legal actions against him.

It is with a sense of wonder that one follows Farrell’s detailed account of these years—wonder that Fo and Rame survived, wonder that they survived as a couple. Fo was a whirlwind of creativity throwing up turbulence all around. Their house was set on fire. Franca was abducted and raped by extremist thugs hired, as it later turned out, by the police. The couple went on producing plays in which they pretended to spray machine-gun fire at the audience or had actors dressed as police burst into the theater and announce that everyone was under arrest. They visited Mao’s China and declared it the perfect society. For years they occupied an abandoned building in central Milan, turning it into a theater and left-wing community. Shown on public television in 1977, Mistero buffo provoked fierce national controversy.

Dario had endless affairs with young actresses. Franca announced she was leaving him in a live TV interview. He wrote letters of apology and reconciliation that reached her when they were published in a newspaper. It was as if a life were not real if it didn’t happen in public. He began to concede her importance and coauthorship of their work. She began to perform monologues of her own on feminist issues. All this while a constant stream of shows was produced, often on controversial questions—Palestine, Chile, drug dealing—about which Fo knew very little. “Years lived at high speed,” Rame later observed. She died in 2013, and Fo in 2016.

What one is invited to consider here is the notion of artists whose work mattered supremely at the moment and in the place it was first performed, and depended largely on the physical presence of the artists themselves. Directors around the world have produced Fo’s work; the British version of Accidental Death of an Anarchist is a rare example of successful adaptation. But the sheer electricity and brazen provocation of Fo’s original performance is hard to recover, even in Italy. Fo, Farrell claims, “was the least autobiographical of writers.” But arguably the plays themselves, his performance of them, were the life, and the marriage. The stage settings were his. He designed and often painted the props. He wrote the songs. He performed himself, directed himself. Rame advised, assisted, edited.

Browsing the scores of videos available online, it’s hard not to feel that Fo is happiest with an adoring audience of young people cross-legged on the floor all around while he performs the monstrous Boniface puffing himself up in papal splendor. But however enthusiastic the audience might be about the moral message behind the material, it does not seem that any transformative anger is aroused, or any compassion for the pope’s victims, nailed by their tongues to church doors. One is simply agog at the extraordinary virtuosity that is Dario Fo.

This Issue

March 12, 2020

Foolish Questions

A Very Hot Year

Serfs of Academe