Crimes have a tendency to become not just stories but genres, once we get too accustomed to them. As more and more stories of sexual assault have been made public in the last two years, the genre of their telling has exploded. One thing we often do with narratives of sexual assault is sort their respective parties into different temporalities: it seems we are interested in perpetrators’ futures and victims’ pasts. Whatever questions society has about the perpetrators tend to concern their next steps: Will they go to prison? What of their careers? Questions asked about the victims—even at their most charitable (when we aren’t asking, “What was she wearing?”)—seem to focus on the past, sometimes in pursuit of understanding, sometimes in pursuit of certainty and corroboration and painful details.

One result is that we don’t have much of a vocabulary for what happens in a victim’s life after the painful past has been excavated, even when our shared language gestures toward the future, as the term “survivor” does. The victim’s trauma after assault rarely gets the attention that we lavish on the moment of damage that divided the survivor from a less encumbered past. One of the things that Margaret Atwood accomplishes in The Testaments—which recently won the Booker Prize (shared with Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other)—is enlarging our perspective by focusing on the aftermath of assault. This engaging sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale tempers the first novel’s grim vision by supplying a parallel text that reveals one of its villains, Aunt Lydia, to have been a rebel in waiting.

The Handmaid’s Tale describes its fictional dystopia, Gilead, as a male theocracy with almost perfect powers of surveillance over its female subjects. What The Testaments proves—reassuringly—is that Gilead’s hegemony was not just incomplete but flawed from its inception: someone was always in fact keeping an eye on the Eye. The horror of the Handmaids’ suffering, which in The Handmaid’s Tale was somehow both sanctioned and ignored, is somewhat mitigated by the revelation that it was always being witnessed: strict records of abuses were being compiled. The Testaments is a text that believes, quite strongly, that dossiers showing wrongdoing by the power brokers matter. Its premise is that if the truth is recorded, exposed, and circulated, consequences will be meted out and power will crumble.

This strikes me as an anemic optimism. If Me Too (not to mention impeachment) has taught us anything, it is that testimony does not dislodge power. We careen from outrage to outrage in a rollicking attention-deficit economy that most perpetrators are able to outwait or outshout. And even when they don’t, no one can agree on how revelations about past abuse should affect the offender’s long-term treatment. Soon enough, they return, and rarely are they much resisted. Jeffrey Epstein was entertained by powerful men after his 2008 conviction for “procuring an underage girl for prostitution” and soliciting a prostitute.

Me Too has altered such calculations by amplifying the survivors’ claims, but even now, after the public disgracing of Harvey Weinstein and humiliation of Epstein, the embarrassed professions of regret from Epstein’s powerful associates feel partial and crabbed. Weinstein was recently out at a downtown comedy club. Many of Epstein’s allies resent that their conduct is up for public discussion at all. As for dossiers knocking down corrupt institutions, well, to take one recent example, Ronan Farrow has alleged that NBC withheld the Weinstein story because Weinstein was threatening to expose similar allegations against one of the network’s own stars, Matt Lauer. Rather than expose both abusers, it kept them both safe. We know all this now, and yet no power structures have toppled. The men who decided to protect Weinstein and Lauer still have their jobs and their influence. Several of Weinstein’s accusers are on the brink of signing a settlement in which he will not have to admit fault or pay a dime himself.

Testimony did not seem to bring a revolution. Yet there is something liberating about this: if the legal system is unresponsive, and power is not collapsing, then why should testimonies be restricted to the formats that the law or journalistic standards require? What little public understanding there is of a survivor’s experience labors under a heap of clichés. The expectations we have for how people should act immediately after being attacked are as strict as they are implausible (she should be beside herself, ideally sobbing, and go to the ER at once to get a rape kit done, and deliver a perfect statement to the police while registering suitable pain and panic).

Advertisement

This is why Chanel Miller’s Know My Name, in which she recounts the experience of waking up to medical personnel and police after being raped while unconscious, is as educational as it is literary. In describing the confusion of reaching back to pluck a pine needle out of her hair and being gently told she can’t, because it’s evidence; of reaching for her underwear and not finding it, and blocking out what that means; of not knowing what happened and realizing that no one quite does—in finding a language for bewilderments that few people have put into words—her testimony is crucial. So is her description of what happened after. Our models for the aftermath of a survivor’s journey usually include revenge, despair, or the fantasy that exposing the truth will provide a just outcome. Miller’s account offers no such catharsis or closure; she describes a jumble of conflicting mental states that proceed along parallel tracks and do not resolve.

When I read E. Jean Carroll’s account of Trump’s raping her, my first thought was that her book excerpt in New York magazine represented almost a rebellion against the genre of “the allegation.” She included reflections a more prudent (or more calculating) narrator might have stripped out, like her provisional willingness to endure a creepy boss if a good steak was on offer, or how pretty she found Trump when she ran into him at Bloomingdales. That peculiar text, which has haunted me since, haunts me precisely because Carroll’s self-presentation is funny, flippant, and unconcerned with appearances. Her final revelation—about what the experience has cost her—transforms the tone. (Mary Karr achieves similar effects in The Liars’ Club.) What stands out in narratives like these is a reckless recognition that, even if the legal system is worth a try (Carroll is now suing Trump), justice is unlikely to follow exposure—so candor is less of a risk.

What I have found myself hungering for, in short, is literature that stretches past legal testimonies and sentimental appeals toward what, for lack of a better phrase, I’m calling post-traumatic futurity. What is the situation of survivors who saw the injury proven and exposed—and maybe even punished—and saw, also, that nothing much changed? I am curious about their vision of things. I want to know how they think things should be. In nonfiction, we have Know My Name. In fiction, we have books like Miriam Toews’s Women Talking and Rachel Cline’s The Question Authority.

Both novels are fictional treatments of real events, both scramble the stultifying formulas we apply to stories of abuse, and both stretch out into subjectivities that feel—if not always hopeful or clear—singular and anchored in the world as we know it. “It’s not like I think there’s no such thing as a sex crime,” a character in Cline’s novel says:

“It’s just the way people think they’re entitled to some abstract justice, some consensus version of right and wrong. I mean, nobody ‘gets her story told.’” She makes air quotes…. “What happened, happened. You have to figure out how you’re going to live with it.”

Set in a fictional Mennonite colony called Molotschna in Bolivia, Toews’s Women Talking begins after the discovery that at least three hundred Mennonite women and girls were anesthetized and violently raped while unconscious by eight men in their colony. The novel is based on real events that took place in the ultraconservative Manitoba Colony in Bolivia, where eight men raped some 130 women over a period of four years.

Through the narrator, August Epp, an outcast who recently returned to the colony and a victim of abuse himself, we learn that a rape occurred “on average” every three or four days, and that the women were blamed by the elders for their wounds or told they’d imagined them. “In the year after I arrived,” Epp says, “the women described dreams they’d been having, and then eventually, as the pieces fell into place, they came to understand that they were collectively dreaming one dream, and that it wasn’t a dream at all.” The culprits were apprehended (as they were in real life) when one woman stayed awake all night and “caught a young man prying open her bedroom window, holding a jug of belladonna spray.” Mennonite men normally police themselves, but one woman (whose toddler daughter was discovered to have an STD) attacked a rapist with a scythe, and a group of men had accidentally killed another. So Peters, the bishop of the colony, asks that the eight culprits be imprisoned by the local authorities for their own safety.

Advertisement

The novel opens with the other men of the colony on their way to bail out the rapists, “and when the perpetrators return,” Epp writes,

the women of Molotschna will be given the opportunity to forgive these men, thus guaranteeing everyone’s place in heaven. If the women don’t forgive the men, says Peters, the women will have to leave the colony for the outside world, of which they know nothing. The women have very little time, only two days, to organize their response.

The novel is the story of their deliberations over those two days. It is also the story of how those deliberations are mediated—first by the narrator, who writes minutes of their meeting in English at the request of Ona, one of his childhood friends, and second by the women’s heady, idiosyncratic arguments, which transcend their subordination and illiteracy. Eight women from two families take the matter up in secret; they meet in a hayloft belonging to a senile Mennonite and, after washing one another’s feet, start debating. The women initially define their options as Do Nothing, Stay and Fight, or Leave. But the conversation digs past the pressures of the present into philosophical first principles: how to argue, and on what basis. When the prickly Mariche observes, for instance, that staying and fighting would mean betraying their vow of pacificism—and would require them to forgive the men anyway if they wanted God’s forgiveness—Ona wonders if coerced forgiveness counts: “And isn’t the lie of pretending to forgive with words but not with one’s heart a more grievous sin than to simply not forgive?”

The women are isolated by design. They do not know how to read, they speak no language other than Plautdietsch, a Low German dialect, which makes the Leave option almost unthinkable; they cannot so much as read a map. Their theological knowledge comes exclusively from the men whose crimes they are now expected to forgive. They know this, and they’re willing to tackle the epistemological uncertainty of leaving. The women have considerable practice achieving precision on improvised terms. Neitje, one of the younger girls, may not know math, but she is the “reigning champion of knowing how much of anything—flour, salt, lard—will fit into any given container so that nothing and no extra space is ever wasted.” Scarface Janz, one of the women who votes for Do Nothing, is “the resident bonesetter, and also a woman known for having an excellent eye for measuring distances.”

Sexual abuse also isolates the victim, this too by design. What’s striking about Women Talking is both how clearly the scale of the assaults enables unexpectedly communal discussions of a post-traumatic future and how hard it is to reach a consensus. The novel dwells (gently, lightly) on how different people approach living in society after being attacked. The women struggle to build a shared set of terms without letting trauma simply flatten their differences. When the elderly Agata cites Ecclesiastes, for instance, Salome—the avenging mother who attacked the attackers with a scythe—is unimpressed, both by the citation and because of the paucity of relevant biblical passages involving women. Stymied, they turn to prosaic animal analogies closer to home. Greta, another elder, observes that her beloved horses fled an aggressive dog. They “don’t organize meetings to determine their next course of action,” she says. “They run.” When one woman laughs and objects that they are not animals, Greta says, “We have been preyed upon like animals; perhaps we should respond in kind.” “Do you mean we should run away?” asks Ona. “Or kill our attackers?” Salome asks.

Interpretations like these proliferate, and so do debates about the interpretations. Agata tells Greta that she has in fact seen horses confront and kill their attackers. She volunteers a story about a mother raccoon who lost three babies to a dog and avenged them by leaving three others for him as bait. Two days after the dog’s disappearance, its owner came home to find “one leg from his dog, and also the dog’s head. With empty eye sockets.” Greta asks sarcastically whether this means they should leave their most vulnerable colony members to be dismembered. “What the story proves is that animals can fight back and they can run away,” Agata replies.

These are the provocative and sometimes frustrating arguments the women talk their way through while sitting on milk buckets, lighting cigarettes, braiding one another’s hair, bickering, and dreading the return of the men. The decision must be arrived at through shared philosophical and theological parameters that they’re developing even as they evaluate how the attack has changed things, and how much. At the beginning, they have a common theology. By the end, though they have reached an accord, one of the oldest will announce that she is no longer a Mennonite.

Rarely, in the course of these philosophical discussions, is the question of pain confronted directly, but mutilated bodies function as a basso ostinato. The skin between a girl’s socks and the hem of her dress reveals chigger and black fly bites and scars from “rope burns or from cuts.” A woman’s finger has been “bitten off at the knuckle.” And yet it feels unfair to group these details in this way, so careful is the novel in introducing such images only when they are strictly relevant, and without sensationalism or comment.

One of the most important characters, Ona, keeps a pail next to her to vomit in; she is pregnant. We discover this consequence of her rape on page 49. We will not learn that her sister Mina hanged herself until page 57—or that at the funeral, Ona herself slid the kerchief around her sister’s neck down an inch to reveal the rope burns. Or that the cause of her suicide was not simply finding her daughter Neitje’s unconscious body smeared with blood and shit and semen after one of the attacks, but the bishop Peters’s insistence that it was the work of Satan. At another point, the grandmotherly Greta removes her painfully large dentures, and we learn that when she had cried out during an assault, “the attacker covered her mouth with such force that nearly all her teeth, which were old and fragile, were crushed to dust.” We learn, too, that “the traveller who gave Greta her false teeth was escorted out of Molotschna by Peters, who then forbade outside helpers from entering the colony.”

If Toews clarifies the smallness of the world these women inhabit, their radicalism sometimes far exceeds our own. At one point Ona, who says she “doesn’t believe in authority, period, because authority makes people cruel,” will suggest they formulate a manifesto. Its provisions are modest: “Men and women will make all decisions for the colony collectively. Women will be allowed to think. Girls will be taught to read and write.” “What will happen if the men refuse to meet our demands?” Greta asks. “We will kill them,” Ona says. The two younger girls “gasp, then smile tentatively.” (Ona’s resolution collapses.)

There is dark humor: one woman volunteers that she had a dream of finding a hard candy in the dirt and wanting to wash and eat it. Before she could, a two-hundred-pound pig pinned her against the wall while she screamed. “That’s ridiculous,” says Mariche. “We don’t have hard candy in Molotschna.” There are terrible moments: some of the women blame Mariche for not stopping her husband, Klaas, from beating her and her children; she is beaten again during their deliberations, and partly because of them. Salome, the mother of the toddler with an STD and guardian of her dead sister’s daughter Neitje, is blamed by Neitje herself for the degrading things she does to keep the men’s attention off her niece. Autje and Neitje trade sex to save old Greta’s horses, arguing that their virginity is already lost. The belladonna spray the rapists used to anesthetize their victims makes a startling reappearance.

Revelations snowball over the course of the deliberations, including the extent of the narrator’s despair and hints of the bishop’s involvement in the rapes. But the novel ends on a note of terrifying hope so pure and desperate and idealistic that it’s almost unbearable. The humility of the novel’s title belies the extraordinary ambition of its characters, who, reeling from trauma, sit, talk, and chart out a future within two days.

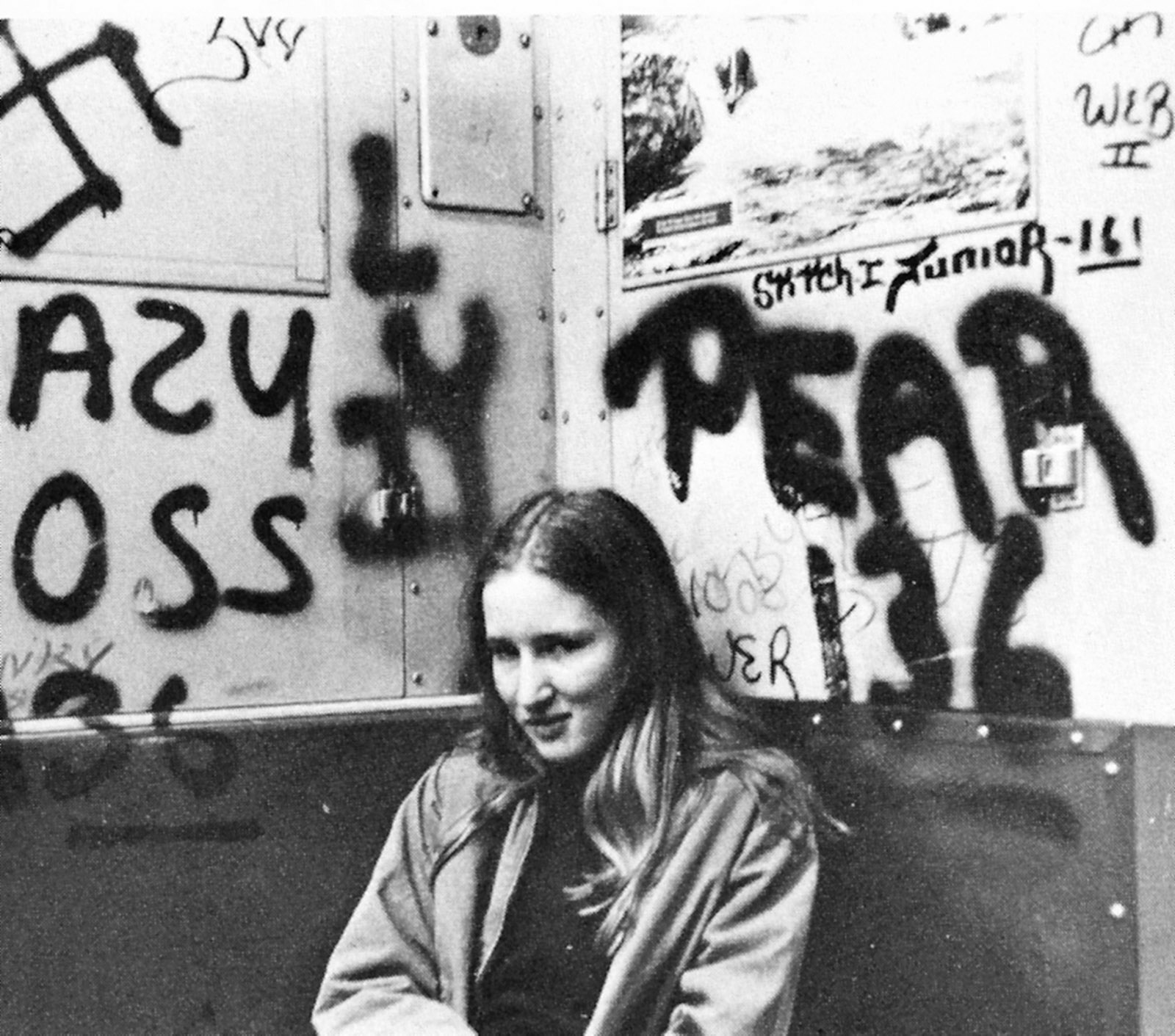

Rachel Cline’s The Question Authority examines a male predator from the opposite end of the ideological spectrum. While the Mennonites are conservative, Bob Rasmussen, a middle school teacher in the 1970s, was the kind of hippie-ish lefty who wore a “Question Authority” button. He tried to construe molesting his students—and pitting them against one another for his favors—as teaching them. The middle-aged narrator, a former student of his named Nora, is mourning her mother’s death and gracelessly inhabiting the impossibly expensive Brooklyn Heights apartment she inherited but can neither sell nor furnish.

She’s stuck. Her options are similarly circumscribed at her new job at the Department of Education in Brooklyn, where her mandate is to settle (not win) lawsuits. While tasked with settling a case with a predatory public school teacher (a “pedo-whatever,” her boss, Jocelyn, calls him) who’s been caught once before, Nora asks why. “First off, they have a union, right?” Jocelyn begins. She notes that no perpetrator is ever caught in the act, and besides, the victim is a teenager, “so half the time they think they’re in love.” “In eighth grade, my best friend was fucking our teacher,” Nora thinks. So were several other girls. When she finally agrees to try to settle with the offender, she discovers that the lawyer defending him has the same name as her childhood best friend.

It’s not a coincidence. The lawyer is in fact her friend, a girl named Beth whom Nora loved but with whom she cut ties. The pain of that separation haunts the novel, and Nora’s shock at encountering Beth prompts a reevaluation of that period in 1971 when Rasmussen dominated their lives. Beth’s reasons for pursuing their teacher make sense: Rasmussen, who gets some first-person sections in the novel, is frank and charismatic; he gave his victims silver bracelets and nicknames. He knew how to appeal to them, made inside jokes in the margins of their homework, told them he knew they were menstruating.

Over the course of the novel, Nora’s reasons for cutting Beth off very slowly coalesce: sometimes it feels like jealousy or protectiveness, sometimes disgust, denial, even shame over her complicity. The breakage is unclean and festering even thirty-eight years after the events that drove them apart (the book is set in February 2009). Where Women Talking considers coerced forgiveness, The Question Authority takes on the ungainly problem of pubescent desire and friendship—and, in a roundabout way, guilt. “The girls in Rasmussen’s class had been fully capable of desire and arousal,” Nora thinks at one point. “Was Rasmussen a criminal? Was I harmed? Was Beth? Men will always desire girls in that maddening stage of beauty…. In any case, I am fine, unharmed, normal. My decisions have been my own decisions.”

Rasmussen was caught and lost his job. He told people he was “in recovery.” But that didn’t end things for Nora, or for the women who remember him. Nora finds a Facebook thread in which classmates who’d been victimized by Rasmussen are discussing whether to join a lawsuit. “What I learned in those days was to be very, extremely wary of leftish males with a cause,” one writes. “He manipulated all of us! When I hear bullshit like, well, it was a small price to pay for learning to think independently (this, of course, only from the un-raped), I am speechless.” “I didn’t have birth control,” one writes in the thread. “U?” “Were you pregnant??” “Yea, I had no idea it was rape then.” “We made cookies after. In his house.”

Glimmering around the edges of this gaunt and lonely novel is the hope that Nora and Beth can reconcile thanks to the shared past that also divided them. When Nora reconnects with Beth, she finds her singularly unshattered—shopping for nice things, casual about a divorce and her son—and discovers that Beth does not see Rasmussen as a problem. She didn’t as a child: “I’m going to have sex with Rasmussen.” she announced to Nora when they were kids, adding that she was going to go to his house and take off her shirt. Nora asks why; they’d made a pact not to succumb to his shtick. “Because I want to,” Beth replies. “I think about it constantly.”

And she doesn’t now. When the two women meet up for drinks (now as opponents in the case concerning the public school teacher), Nora asks Beth, who says she dabbled in sex work, if she holds Rasmussen responsible for anything. Beth tells her not to be ridiculous, but Nora presses: “It sounds like there might be a connection, don’t you think? Between being molested by your teacher as a fourteen-year-old and becoming a prostitute?” Beth scoffs, and wonders if Nora blames the teacher for making her an old maid. It’s a brittle encounter, and Beth adds that Nora’s ending their relationship was worse than anything Rasmussen did: “You want me to blame Bob but you’re the one who broke my heart.”

There is no consensus about trauma or justice or even what their past meant, and it’s painful in ways that Toews’s novel almost perfectly opposes. Cline structures The Question Authority by alternating chapters from a few different points of view, including those of Nora, Rasmussen’s then wife Naomi, and e-mails between Rasmussen and a grown-up Beth. It’s a confusing kaleidoscope of perspectives until you realize, alongside Nora, that Beth isn’t viewing the episode as if over a chasm of thirty-nine years. It turns out that she reunited with Rasmussen as an adult, and married him. “She sleeps in his bed,” Nora thinks. “He didn’t die, or go to jail, or fall into a hole in the earth. And what’s more, he is loved. The ways Beth tried to manipulate me into settling the case this afternoon now seem diabolical instead of pathetic.” Is Nora an “old maid” because of Bob? It’s hard to say; that her life is emptier without Beth is much clearer. So is the shocking revelation that Beth might be using their connection to win her case and let yet another predator continue unimpeded.

This is, in other words, less a story about victim and abuser than of how a formative friendship failed to survive the abuser’s interference. In Cline’s hands, it’s also a story toggling between self-righteousness and self-doubt. Nora’s certainty about what happened is believably unstable. “Beth and I often argued,” Nora observes. “In retrospect, the subject seemed to have always been a version of the same thing: what was the truth and which one of us understood it?” Our protagonist fancies herself the less deluded party: when she pointed out that the wood paneling in Beth’s room wasn’t real, Beth wouldn’t have it. And she credits herself with seeing through Rasmussen: “I try to picture how a pedophile operates in a school. Of course, I already know: he writes understanding notes in the margins of the girl’s homework, tells her she’s pretty, that she can come to him any time she ever ‘needs to talk.’”

“I have always looked at things a little too closely,” she says elsewhere—a self-assessment that gets challenged more than once over the course of the novel. Nora misses a great deal. She didn’t realize that Beth was going to Hebrew school the entire time they were friends. She forgot, or blocked out, that she did not, in fact, wholly reject Rasmussen’s advances. Beth offers her a photograph as quiet proof, and Nora’s world turns upside down. But these conversions do not amount to repair: Beth’s life falls apart by the novel’s end, but she and Nora never reconcile. A brief window opens, during which Beth can explain why she married Rasmussen: “It was more like finding a lost part of myself,” she tells Nora one night. “Like he connected the dots for me between who I am and who I used to be.” That window closes; by novel’s end, they’re still on opposite sides of the courtroom. Beth vanishes without saying good-bye.

The conventional wisdom is that thirteen-year-olds’ crushes on teachers do not amount to consent. But that’s a legal view, not a survivor’s, and The Question Authority gets weaker the closer it hews to a legal rather than an interpersonal perspective. The latter is messier; teens, for example, tend to believe in their own agency. Nora struggles to reconcile the real desires of her younger self (and Beth’s) with the gaps in her understanding; young Nora thought, for instance, that Rasmussen’s “Question Authority” button meant he was “the authority on all questions.” She thinks often of a photograph of a girl named Tamsin—one of Rasmussen’s victims—as “a picture of a girl enmeshed, trapped, but believing herself to be a willing volunteer.” The line between being trapped and being willing is thin. Nora misremembers that photograph in a way that turns out to be significant, but she still tracks Tamsin down. “I’m so sick of that story,” Tamsin says of her former teacher. “I used to think it defined me, you know?” She says he raped her while she said “no.” And she still wears a silver bracelet.

If assault allegations conform to a bland and legalistic formula, the long aftermath of a traumatic experience follows no similar or even knowable arc. In The Question Authority, trauma isolates, even when best friends go through it together. But this is why Me Too was so surprising; meaning is relational, and unexpected things happen when so many lonely people find that they were not—in their confusion, curiosity, and need for a future conceived along entirely different lines—alone. Survivors dealing with a loss of control over their lives have few ways of narrating the past that restores control and serenity: to insist on your agency as a teen is to assume enormous guilt for your own desire and vulnerability.

This seems to be Beth’s conundrum. To assume you had no agency is to accept powerlessness—no easy prospect either. No wonder Nora erased her encounter with Rasmussen altogether. No wonder neither woman can admit that aspects of her past have shaped her present; better to compartmentalize and split it off to grasp a sense of sovereignty. The Question Authority is a hunt for a narrative—an authority, even—that permits a person to feel autonomous and at peace with herself.

It occurs to me sometimes—when Me Too is accused of painting with too broad a brush—that outrage and nuance are hard to sustain simultaneously because they cancel each other out. A plea for the one effectively nullifies the other, and this destructive interference gives a false impression. When grappling with sexual misconduct, our embattled society tends to turn one party into a monster too difficult to imagine and the other into a victim so damaged that no future seems possible. This pattern has serious formal as well as narrative failings. It doesn’t give much berth to the wide array of responses people actually have, to both abuse and its exposure, in the short and long terms—a range that can include despair but also other qualities, including ambivalence, fury, grief, numbness, denial, and what I’ll sloppily call hope. That might not be the precise word for what Toews’s and Cline’s imaginative efforts evoke, but I’m grateful for their deep involvement within these awful constraints.

This Issue

March 12, 2020

Foolish Questions

A Very Hot Year

Serfs of Academe