The black individual passing for white in nineteenth- and twentieth-century American fiction by white writers is usually a woman, and usually when the truth emerges, the purity of the white race is saved. However, in An Imperative Duty (1891) by William Dean Howells, a Boston girl is ashamed to find out that legally she is colored, but her white suitor marries her anyway and takes her off to a life in Italy. In the beginning of Charles Chesnutt’s The House Behind the Cedars (1900), a “high-bred” black man in North Carolina returns to his hometown to ask his sister to take his dead white wife’s place and bring up his son. A young aristocrat she meets in her new white life proposes marriage, but soon learns the truth of her origins. Literary convention, in the form of a fever, kills her. The white suitor realizes too late that love conquers all. He promises to keep the brother’s secret.

The secret was as radical as Chesnutt could get. From a North Carolina family of “free issue” blacks—meaning emancipated since colonial times—Chesnutt had blond hair and blue eyes. He wouldn’t pass for white, because if he became famous then he chanced someone appearing from his past. He preferred to pursue reputation as a black man. Chesnutt had cousins who crossed the color line and he never told on them, viewing passing as an act of “self-preservation,” a private solution to the race problem. The big escape from being black was an American tradition. Three of Sally Hemings’s six children ended up living as white people.

The nameless narrator of James Weldon Johnson’s novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man (1912), a widower and a father, says little about his life as a white man. He is interested instead in his past as a black person, his life with different classes of black people, his wanderings around Europe as a young musician. When he returned to the United States and went on a folk song–collecting tour of the South, he witnessed a lynching—a black man being burned alive. Terrified, he got himself across the color line. He didn’t want to belong to a racial group so utterly without power.

An awkward work, Johnson’s novel nevertheless challenges the genre of passing literature because there is no trauma of exposure, however ambivalent the narrator is about his choice at the novel’s end. The Ex-Colored Man regrets that his security has come at the expense of the composer he believes he could have been had he stayed black. He is keenly aware that he removed himself from an environment that would have nourished him as an artist. Johnson’s premise mocks the notion of racial purity, while the injustices that come with being black make for his larger subject. At the same time he’s saying that maybe being white isn’t what it’s cracked up to be, that for all the material rewards of his business ventures, maybe his life as a white person is less rich in important ways than it could have been, though he loves his family, and his wife had been in on his secret.

Johnson put his name to the 1927 edition of his novel, but when it was first published, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man was said to have been written “by Anonymous,” enhancing the sense that the narrator was still out there, an infiltrator who had succeeded in insinuating his legally-defined-as-black self into the Nordic gene pool. Laws defining who was black varied from state to state, but the drop of black blood—one grandparent or even one great-great-grandparent—was the “taint” that white society was psychotically on guard against. In Nella Larsen’s Passing (1929), a black woman whose racist white husband doesn’t know she is black talks about the ruin of giving birth to a baby too dark. In fiction about passing, interracial union has already happened, whether consensual or forced. The protagonist begins life as a carrier of the taint. What makes Larsen’s novel so striking is its cold, utilitarian atmosphere of let the joke on the lawgiver be.

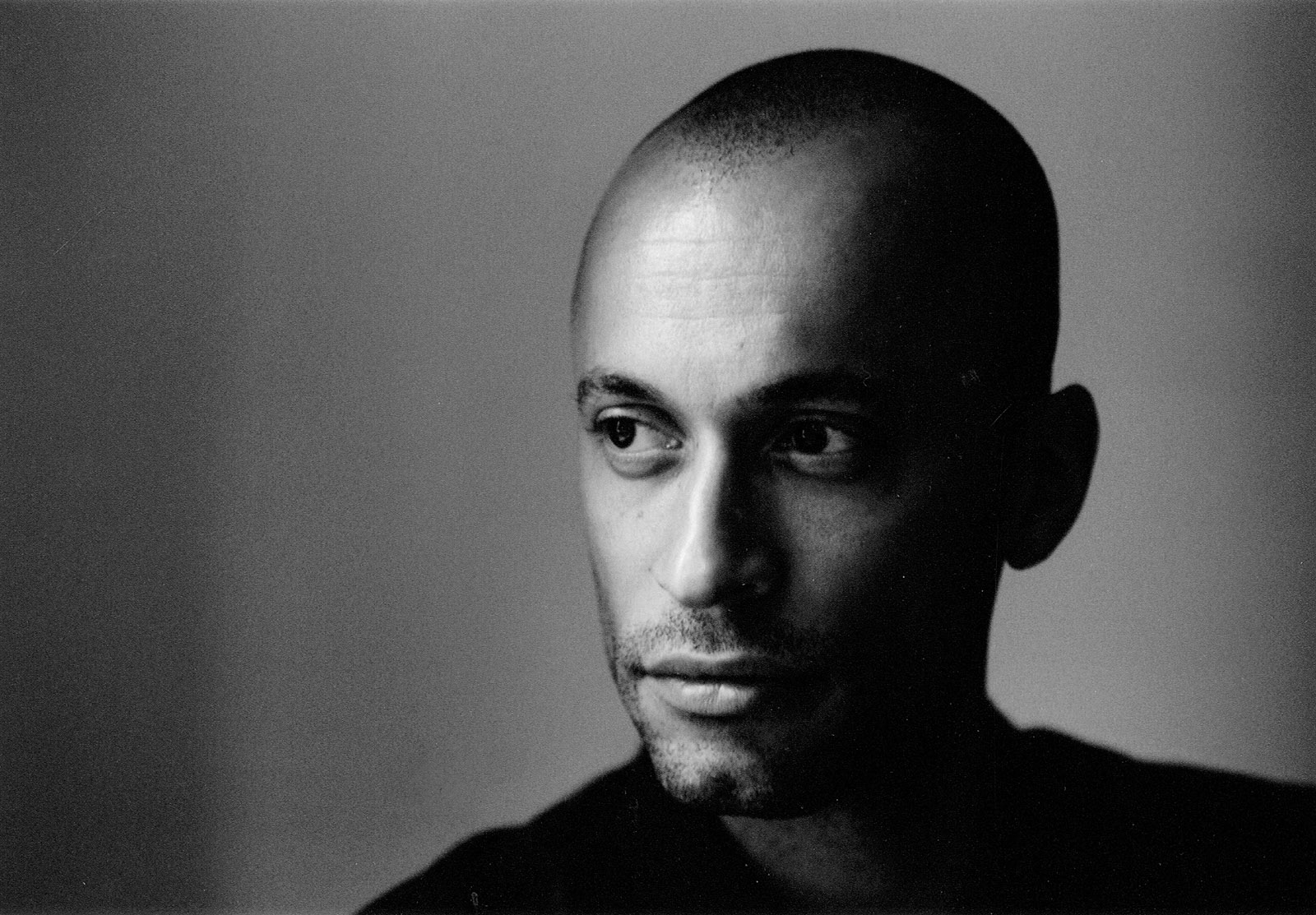

In the considerable American literature about stepping across the color line, nothing matches Anatole Broyard’s Kafka Was the Rage: A Greenwich Village Memoir (1993) for lack of conscience. Broyard, a distinguished New York Times literary columnist for many years, presented himself as white, though enough people knew otherwise. Yet he insisted on the mask. In his memoir, published posthumously, Broyard brilliantly evokes the intellectual excitement and amorous joy of the Village in the immediate postwar years. The whole time his black family was living just over the bridge in Brooklyn. He simply never mentions them. “Racial recusal is a forlorn hope,” Henry Louis Gates Jr. said in his portrait of Broyard in Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man (1997). “In a system where whiteness is the default, racelessness is never a possibility. You cannot opt out; you can only opt in.” For a black person to pass for white means that the rational self and the real self can never be reconciled—we assume.

Advertisement

It’s remarkable that the subject of passing and the predicament of the tragic mulatto persisted in American popular culture for as long as it did. Fannie Hurst’s best seller about passing, Imitation of Life (1933), was made into a film in 1934 and again in 1959, the second version directed by Douglas Sirk. The fiction about passing is romantic, expressing compassion for the black person perpetrating the fraud. But the color line was a policed border well into the civil rights era. “The ‘Negro race’ is defined in America by the white people,” Gunnar Myrdal observed in that graveyard of liberal philosophy, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944). He added that any analysis of passing would always be conjecture, but it seemed that migration and the increasing anonymity of urban life had made it easier and that, surprisingly, black men were more likely to pass than black women. Renee C. Romano’s bleak study, Race Mixing: Black-White Marriage in Postwar America (2003), relates how in the 1940s and 1950s the courts routinely sided with white grandparents or the white parent in custody battles between divorcing interracial couples. To be brought up white or among white people was in a child’s best interest, the white parties contended. The Supreme Court didn’t overturn all laws against intermarriage until 1967.

A black person who wanted to escape being black was also getting away from generalized ideas of blackness. Birthright (1922) by T.S. Stribling, a white writer, charts the disillusionment of a Harvard-educated black man who has returned to his Tennessee hometown as a teacher. He finds black life too squalid for him to have any effect. It isn’t clear if he and his fiancée are intending to pass for white when they leave, but they feel that by going North to the culture they want to belong to, they are escaping perdition. Stribling was seen as a social realist: he was making the point that black people were the way they were because of the degrading conditions in which they lived, not because of traits they were born with. But Claude McKay charged that Stribling’s black characters conformed to the same racist stereotypes as those of any white writer who portrayed the social inferiority of black people as an expression of supposedly innate racial characteristics.

Harlem Renaissance writers viewed the black masses as the keepers of blackness; no longer were they prisoners of it. A black person’s estrangement from the black masses was therefore sometimes depicted as a false or European culture suppressing the true one. The class question got lost in ideas having to do with a racial essence. In Carl Van Vechten’s Nigger Heaven (1926), a prim black girl is in despair that she is too cultivated to get in touch with her inner black self should it really be there, and maybe she doesn’t want to anyway.

The desire to pass, to escape being black, and the urge to get away from blackness, to live separate from black communities, may have had the same motives as the dream of transcending race, but philosophies that called for doing without racial categories sought to address the social definitions of what it meant to be black—by being open about the heritage of race-mixing that excited whites to violence. Race transcendence tended to mysticism in the Harlem Renaissance writer Jean Toomer, who made a sensation in literary circles with Cane (1923), his expressionist meditation on his experiences of the black South. He said he was a mixture of French, Dutch, Welsh, Negro, German, Jewish, and Indian, and had lived on both sides of the color line, but his desires as an artist pulled him “deeper into the Negro group.” He didn’t stay in that group for long.

Toomer was handsome and light-skinned. He said that “I have the appearance of a sort of universal man” and that people had taken him for “American, English, Spanish, French, Italian, Russian, Hindu, Japanese, Romanian, Indian, and Dutch.” His ability to belong to different groups served to “nonidentify” him. Toomer became a student of George Gurdjieff’s in 1923, and the next year he returned from the Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at Fontainebleau an “earth being.” He died a Quaker forty years later, never having had another commercial publication.

George Schuyler, the Mencken-like Harlem Renaissance satirist who late in life became notorious in black America as a conservative opponent of Martin Luther King Jr. and the 1964 Civil Rights Act, proposed in 1929 in a pamphlet, Racial Inter-marriage in the United States, that the race problem could be solved by intermarriage. His daughter, Philippa Schuyler, born in 1931, a musical prodigy, he regarded as an example of “hybrid vigor.” Yet the Schuylers were also behaviorists, determined to apply the ideas of the child psychologist John Broadus Watson, who had been a student of Pavlov’s and discounted the influence of heredity. Schuyler’s white wife kept her child’s existence a secret from her Texas family for years. She reared Philippa on raw meat, corporal punishment, music lessons, home study, and open discussion. Philippa was welcome to make inquiries about her father’s penis when she was three years old. As an adult, she sometimes found it convenient to pass for Spanish when she traveled.

Advertisement

Father Divine, the Harlem cult leader of the 1930s, described his refusal to recognize race as “racial indiscrimination.” He forbade the white and black members of his Peace Mission from using the word “Negro.” They were either “light” or “dark” and they were seated alternately at Father Divine’s banquets in celebration of his munificence. He defied segregation wherever he could: “My people are the peoples of the earth.” Personal utopianism promised psychological independence from the repetitive propaganda of race.

Psychological studies in the Black Power 1970s described “nigrescence,” the process of becoming black, the movement from an old to a new black identity. The Racial Identity Attitudes Scales that psychologists devised to track the path to self-acceptance were available to all. In tests with black children, even a preference for white dolls was not a sign of pathology, nigrescence research assured us. There was no need to sneak out of the black race anymore, to be the type of black person whose distance from other blacks disguised self-hatred. Black was cool, and every shade of black person could be black enough on the inside. But the long ago can drive back into town and ring your bell in the middle of the night.

Thomas Chatterton Williams, who belongs to the hip-hop generation of multiculturalism and diversity, is willing to risk being a throwback in his memoir/essay Self-Portrait in Black and White: Unlearning Race. To speculate on the racial future, he goes back to the days when the black individual who could do so took the side exit from segregated life to personal freedom. He deals with passing for white, class privilege, and his hopes for the possibilities of race transcendence, knowing perfectly well that because he is light-skinned he can contemplate racial identity as being provisional, voluntary, situational, and fluid. Throughout his memoir, Williams is thinking more of Camus than he is of Fanon:

I start from the premise that, though forces beyond my control influence and pressure and certainly constrict me, I am ultimately responsible for my own beliefs and actions. Even as a member of a historically oppressed minority, I can still define myself and in so doing exercise my agency, irrespective of how society reacts to me.

Williams’s first memoir, Losing My Cool (2010), tells the story of his father’s determination to keep him from gangsta rap culture when he was growing up. His father, a black man who looks black, figures significantly in Self-Portrait. In 1968, when he was executive director of the San Diego County War on Poverty, he met Williams’s mother, a white girl, recent college graduate, and devout Protestant. They married five years later, once he “was convinced that they were individually robust enough to withstand the ostracism and scrutiny they would surely encounter—especially once they decided to have children.” They moved east, far from relatives. Williams and his brother “grew up with zero extended black family contact and very close to zero extended white family contact, too.”

He had to learn “blackness.” Eventually it “inhabited” him as a middle-class youth. It was not only a question of deciding what he looked like, but of how he spoke, dressed, met the world. Blackness was rhythm and athleticism, he says. “Blackness was what you loved and what in turn loved or at least accepted you.” In Self-Portrait, Williams reconsiders his experiences in high school, then how his college years at Georgetown University changed him. He examines his family relationships, including his meeting late in life with his religious maternal grandfather who had refused to visit when he was growing up. During his first sojourn in Paris (where he now lives), the Arabs he met spoke to him in Arabic, because he looked like someone from their part of the world. In his Brooklyn life, he was deep into discussions about race on social media, suspecting that Michael Brown maybe wasn’t entirely innocent in Ferguson, but not doubting what happened to Eric Garner in that chokehold on Staten Island.

Williams has looked at writings from Linnaeus to the Journal of Critical Mixed-Race Studies. He was especially drawn to Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life (2012) by Barbara and Karen Fields, who argue, as he puts it, that racism created race, and even with our willingness to speak out against racism we take the “concept of race as an implacable given,” perpetuating the problem. Everyone—blacks, whites of goodwill, Asians, Latinos—should “remove themselves from the confidence game,” he advises. The “disinvestment from the politics of racial identity” would let “entire classes” of Americans focus on their shared vulnerabilities.

“I am not renouncing my blackness and going on about my day,” Williams says. “I am rejecting the legitimacy of the entire racial construct in which blackness functions as one orienting pole.” Though Williams is impressed by Adrian Piper, the philosopher and conceptual artist who in 2012 publicly “retired” from being black, her recent Escape to Berlin: A Travel Memoir (2018) shows that her retirement hasn’t lasted. Even when you’re done with being black and blackness, it seems that you cannot cease explaining why.

Racial difference may be an economic, political, biological, or cultural problem, but it’s also a philosophical and imaginative disaster, Williams thinks. While “racism rooted in centuries of skin bias is persistent and feels more urgent than just about anything else when you bear the brunt of it,” he doesn’t see why we can’t resist bigotry and at the same time imagine a society that has “outgrown the identities it preys on.” The world is used to race mixing, and people aren’t the sum of their ethnic characteristics anyway. We talk about race when we mean class—manners, values, taste. “We don’t have to limit our points of reference and inspiration to identity groups that perpetuate the idea of racial difference. We can also choose to expand our vision of ourselves, and bring about a fuller rendering of our common, complex human condition.” Racial injury has harmed us all; let’s grieve, but let’s fix it by rejecting the logic that perpetuates the injury: “It is my hope that as many people as possible, of all skin tones and hair textures, will come to turn away from the racial delusion.”

Having looked at the color line from both sides, Williams says he has a “dual perspective,” like that of Walter White, James Weldon Johnson’s NAACP colleague, who in the 1920s used his blond hair and blue eyes to sit in on Klan meetings. (Thirty years later White lost respect among many blacks by publishing a satire in which a miracle chemical solves the race problem by turning everyone white.) Williams wagers that in an age of dangerous populism his dual perspective is a better way of seeing race than always going on about white supremacy.

Williams remembers not taking his wife to a dinner for Ishmael Reed at the Paris home of the saxophonist David Murray, only to be surprised that his heroes also had white wives. Reed would have remembered the East Village of the early 1960s, when most of the black men in radical black organizations had white lovers. Half a century later Williams is asking “why it is so often the case that men like us, men who tend to be paid to think about and engage critically with the subject of race…why is it that we have all made our lives with white partners?” He wonders if “marrying out” could be an “indispensable” part of the solution “to the quagmire of racism without race,” not a tribal betrayal. When Williams’s father met his fiancée, a blond French girl,

I think that what he saw between Valentine and me was a kind of freedom—a sovereign liberty to improvise and create the self without external constraints, which in truth he had always prized above just about everything. In this way, the black tradition my father belonged to was the open, omnifaceted one of Albert Murray and not at all that closed and spiteful one of Eldridge Cleaver: black American life, while certainly conditioned by local historical circumstance—and thus distinct from other strands of the African diaspora—was not beholden to it. It was a racial irony or ambivalence that would take me several more years to understand clearly.

What comes through in Self-Portrait is a son’s pride before his father that in him the family continues its rise, gets even farther away from those shameful Texas cotton fields. He lives in France, more comfortable with his wife’s maternal grandmother and her long family history of answerable questions than he is with the unspoken feelings on his mother’s side and the history that can’t be known on his father’s. This conjunction of histories in his own life has shown him that race can be transcended “especially at the interpersonal level.” Blackness, like whiteness, isn’t real, Williams declares in his concluding chapter, “Self-Portrait of an Ex-Black Man,” and he refuses to feel guilty anymore for saying so, contradicting his earlier assertion that he was not renouncing blackness and going about his business:

Virtually all of our most audible voices on race, today more than ever, in establishing identity solely in “the body”—no matter in how positive, persuasive, or righteously indignant a light—actually reinforce the same racist habits of thought they claim to wish to defeat. I do not mean this last point rhetorically—I mean it literally. Black Lives Matter, for example, is a cause whose aims—primarily the work of drawing attention to the severe abuses of the criminal justice system—I overwhelmingly share. Yet its very framing—the notion that some lives are essentially black while others are white—is both politically true in a specific sense and, in a broader way, philosophically inadequate.

Williams accuses others of giving whiteness too much value. To strike a balance, he must devalue blackness, without sounding like a neocon or the dreaded self-hater. Parenthood supplies the social magicianship. Williams wants to imagine a burden-free future for his children. He is “relieved” that there will be no vulnerability of the body for his children, first a daughter and then a son. They are white or white-looking and not likely to experience racial discrimination or racial violence. They will not be “irrevocably stigmatized by the inhumanity of chattel slavery.” He is full of the magnanimity of protective fatherhood and does not want any of us to be defined by the sordid past.

Temperament, era, geography, and gender matter when looking at the literature about seeking release from destructive racial subjectivities. The poet Toi Derricotte, who suffers from depression and is haunted by memories of an abusive father, recalls in her memoir, The Black Notebooks: An Interior Journey (1997), that an elderly relative told her the family had worked too hard to look the way they did for her to mess them up by marrying the wrong man. Derricotte comes from generations of Louisiana “bright folk”—black people who look white. Her banker husband looks black, and realtors show her different properties when she is by herself. Neighbors in the upper-middle-class New Jersey suburb where they lived for more than a decade never asked them to join the country club.

When Derricotte was first starting out as a college teacher, she wasn’t trying to pass, she just didn’t say in certain professional situations that she was black. She has plenty of examples of white people making racist remarks when they think the company is all white: “I cannot conceive of white people having a communal pain that equals the compelling energy and focus that comes from being black in our society.” However, if she has been around white people for a while, then she is momentarily thrown when she again finds herself with a black person.

Her memoir describes the culture of what Alice Walker first called “colorism,” the prejudices among blacks based on skin tone. “If you’re light, all right; if you’re brown, stick around; but if you’re black, get back.” Studies such as Margaret L. Hunter’s Race, Gender, and the Politics of Skin Tone (2005) compare how light-skinned black students and dark-skinned black students are treated in the classroom. Darker students are more likely to be treated with suspicion and not seen as academically promising.

Williams thinks of “colorism” as a power imbalance. Yet he hesitates to dream of a new caste in the West, because of the class implications: “With the one-drop custom I was born into now at long last on the wane, could the rise of a comparatively privileged, white-beige population (including ever more Asians, Latinos, and further decreasingly ‘black’ mixtures), unburdened by such concerns and—as technical minorities themselves—impervious to accusations of ‘white privilege,’ result in a stigmatized, dark-skinned population’s further neglect?” He recommends detachment to everyone even as he says that it’s hard for him to talk to young black audiences in the US about his coming-of-age memoir, because he realizes that his experience of what it means to be black has now with his career veered so far away from theirs.

After the 1960s revolution in mass black consciousness, celebrating the earthiness of blackness was often written about as a measure of a black person’s self-acceptance. The light-skinned, Radcliffe-educated narrator of Andrea Lee’s Sarah Phillips (1984), in Paris in 1974, decides to go back to the US after her rough trade French boyfriend teases her in bed—as she has urged him to do—about being descended from a half-Irish, half-Jewish mongrel who was raped by “a jazz musician as big and black as King Kong.” She says the racism of his remarks didn’t wound her as much as it reminded her how futile it was to try to escape America. Lee’s novel suggests that the black person deciding to go home is another literary convention, a trope picked up from James Baldwin, serving the same moral function as the heroine renouncing the white man in the passing novels as written by black women in the late nineteenth century.

Richard Wright and his Jewish-American wife moved to France in 1947, in part for the sake of their children. He never went back to the US, dying in Paris in 1960, still an exile emotionally. Baldwin also remained an expatriate, like Chester Himes, who simmered away in Franco’s Spain at a time when most artists boycotted the country. Baldwin’s contemporary William Gardner Smith married into France, so to speak, and found employment with Agence-France Presse. Two of his five novels, Last of the Conquerors (1948) and The Stone Face (1963), deal with nonwhite people confronting racism in postwar Europe. William Demby, another black novelist of Baldwin’s generation, worked for Federico Fellini and Roberto Rossellini in Rome. His novel The Catacombs (1965) tells the story of a black American girl abandoned by her aristocratic Italian lover when she becomes pregnant. In his long life in Italy, Demby married the writer Lucia Drudi and had a son.

Apart from Himes, these black writers had white wives or white long-term girlfriends, but they were not themselves light-skinned. They were getting away from US racism, not getting away from being black. Europe was a refuge, but to be an expatriate was still something like passing, a personal response to American racism that brought with it the anxiety that privilege and luck were forms of betrayal.

Vincent O. Carter felt suffocated by the life blacks could lead in Paris on the GI Bill. He moved to Bern, Switzerland, in the early 1950s to get away from other blacks, and therefore from himself. He was the only black in the city at the time. In his memoir, The Bern Book (1973), he is frank about the resentment he felt when a delegation of Ethiopian diplomats passed through town, as though their presence made him less special. He died in Bern in 1983. That same year, novelist Frank Yerby, Himes’s contemporary, gave a news agency an interview in which he said, “You can call me racist if you like, but I dislike the human race.” Yerby published more than two dozen popular romances and historical novels that sometimes had black characters. “But do not call me black,” he said. He claimed to have more Seminole than black blood. Yerby had a Spanish wife and family and died in 1991 in Madrid, where he had been living since 1955.

Andrea Lee’s Russian Journal (1981) chronicles her year in Moscow when her Italian husband was a graduate student at Moscow State University. They spoke Russian, made friends, and shared Soviet life, up to a point. Lee is the observer, keeping a tender focus on her Russian subjects, never mentioning that she is black. Light-skinned, she was not what Russians expected when they thought of black people. Whatever the official ideology or the political culture that used to equate the Russian soul and black soul, Soviet society was racist. Lee’s situational passing, the absence of scenes in which her being black is acknowledged or judged, lets her borrow American power. She was at an advantage in her exchanges, because the Russians she encountered saw her as the white American, someone from a land of plenty and not from a group that commanded little respect.

Lee and her husband settled in northern Italy and had a family, and she began exploring, “both in life and in art, what it means to be a foreigner.” Racial identity comes up in her fiction and autobiographical essays, as it does in the political fiction of Jake Lamar, who lives in Paris. Europe isn’t all white anymore—it never was—and black American writers share a cultural landscape with black writers in English from other places, such as the Afro-British novelist Sharon Dodua Otoo, whose first work, the things I am thinking while smiling politely (2012), follows a black woman in Berlin as she recovers from divorce from her German husband. These writers represent a new generation in a long tradition of thinking about race and racism by changing the setting. In their work, aspects of black identity are examined as parts of intimate relationships.

Thomas Chatterton Williams belongs to this tradition, and maybe inadvertently to another he’d rather not be identified with: light-skinned black people who place a value on whiteness; he is kidding himself when he says he doesn’t. If it’s uncool these days to say that people clearly in between black and white ought to be exempt from racism or treated as exceptional when it comes to defining blackness, then maybe it will be OK to say that it is time to allow into our heads the possibility of the Brazilification of the United States. Some Brazilians resent the several official racial categories in their country and argue that these groups are more cultural than racial. The same could be said for Williams’s new global “white-beige” elite, sweetly desperate though he is to give old attitudes new names.

Williams seems to assume that anybody light-skinned is waiting by the same exit door that he is declaring open to his offspring. But there can be a moral choice in belonging to a group. Some time ago I was on a panel with Celeste Headlee, a young journalist who described Obama as mixed-race. I laughed and said he wasn’t mixed race, he was black. The audience laughed with me. Afterward Headlee took me aside. She could have called me on it during the panel, but her manners had her wait. “You think I’m white, don’t you?” In fact, she is the granddaughter of the distinguished black composer William Grant Still. It was her turn to laugh.

Race transcendence is still a crank’s racket, but it is usually offered in the spirit of a gift to humanity. Self-Portrait in Black and White: Unlearning Race, this cheerful manifesto of the light-skinned and well placed, carries an atmosphere of gratitude for the acceptance France has promised Williams’s children. He has assured himself that in these times of tattoos, manipulations of the body, gender subversion, transition, transformations of the self, class fantasies, and cultural smugness, not much essentialism remains in definitions of blackness. We are saved already if we but knew it; we are already well, sound, and clear; we have only to recognize it.

This Issue

March 26, 2020

The Party Cannot Hold

Left Behind