When, in 1993, the editor in chief of Literary Review, Auberon Waugh, together with the critic Rhoda Koenig established the annual Bad Sex in Fiction Award, their declared goal was to expose what they saw as the deplorable ubiquity of “crude, tasteless, often perfunctory use of redundant passages of sexual description in the modern novel, and to discourage it.” Extracts by the shortlisted and winning novelists in the many years since might well leave a reader thinking there really is nothing harder to write about than fucking. (Without a doubt they will leave the reader rolling on the floor.) Back in the days before most MFA students had become too fearful of being called out for politically “problematic” content to include sex scenes in the fiction they submit to workshop, a teacher knew what three pitfalls to expect: either the description would be too clinical or it would be too coy or it would be too smutty. Bad sex writing happens even to seriously good writers (John Updike, famed for his bravura powers of description and the meticulous elegance of his style, was also the winner of a Bad Sex in Fiction Lifetime Achievement Award), giving strength to the idea that describing this particular human behavior, however important a part of life it may be, is so fraught, so likely to break the spell every novelist strives to cast and maintain over the course of a book, that the best thing might indeed be just to avoid it.

Jonathan Franzen, in an essay on books about sex, described the unpleasant feeling he experiences as a reader at the signs of a looming sex scene:

Often the sentences begin to lengthen Joyceanly. My own anxiety rises sympathetically with the author’s, and soon enough the fragile bubble of the imaginative world is pricked by the hard exigencies of naming body parts and movements—the sameness of it all.

The sameness of it all: one of the hallmarks of pornography. “When the sex is persuasively rendered,” his complaint went on, “it tends to read autobiographically.” True, and, if not off-putting to everyone, this surely risks making many other readers besides Franzen cringe. But the greatest challenge, the one that even the most gifted writers almost never transcend, remains the limits of our erotic vocabulary, now and forever “hopelessly contaminated through its previous use by writers whose aim is simply to turn the reader on.” Having thus hit the nail on the head, Franzen himself went on to be shortlisted for the Bad Sex in Fiction Award, for a passage in his fourth novel, Freedom.

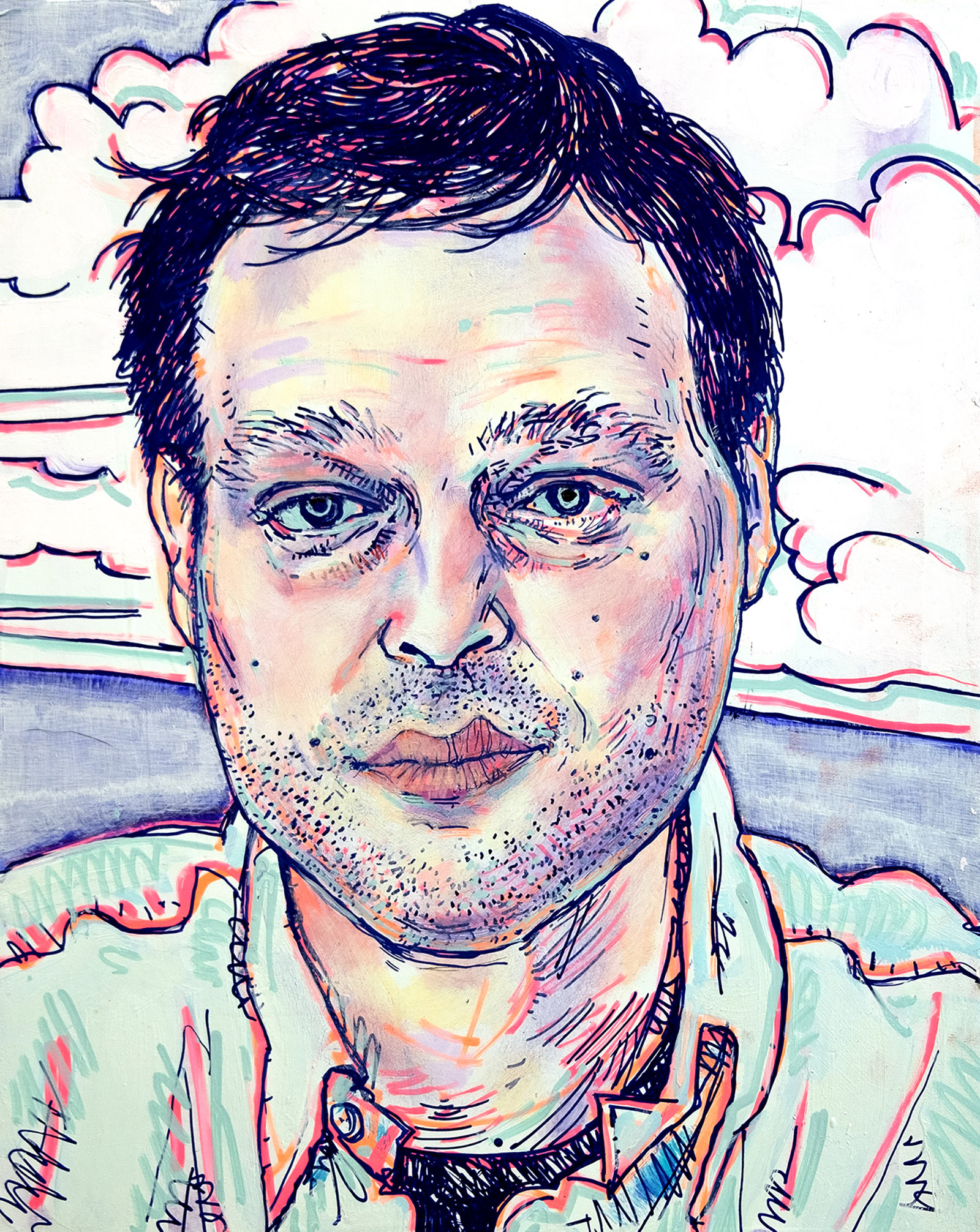

So what happens when someone sets out to write fiction that is “100 percent pornographic and 100 percent high art”? According to Garth Greenwell, that was one of his goals in writing Cleanness, a collection of stories so connected they can be read as a novel (he himself has called the book a lieder cycle) and which includes several graphic descriptions of sex, some loving and tender, some brutally S&M, and all tending to read autobiographically. (Like his fictional unnamed first-person narrator, Greenwell is gay, was raised in a southern Republican state, and has lived and taught in Bulgaria. A recent profile in The New York Times suggested that, despite these parallels, readers who assume Greenwell is writing about himself are mistaken. However, when I asked him if it would be appropriate for me to include his work in a course I taught on autobiographical fiction, and if I had his approval to do so, he said yes.)

Greenwell, who before turning to fiction wrote poetry and who has also been a dedicated student of music, published his first book in 2011. Mitko, which won the Miami University Novella Prize, is set in the Bulgarian capital of Sofia, where the book’s narrator, a young American writer, lives alone and works as a teacher in an American high school. Beneath a government building in a public bathroom frequented by men seeking anonymous sex, he pays for the services of a young hustler—Mitko—thus initiating what will become an increasingly intense and complicated affair. Handsome and alluring, Mitko turns out to have other charms as well, displaying at times an appealingly childlike side, affectionate and marked by the kind of innocence that is owing not merely to his youth but to the severely restricted life that has been available to him. Without money, without education, and, like so many of his countrymen, without prospects for decent employment, Mitko is basically homeless.

Unsurprisingly, he has a dark side too. A heavy drinker, habitually dishonest, he can also be coldly manipulative, bullying, and worse. The narrator’s attraction to Mitko does not blind him to the considerable risk their relationship involves. To keep seeing him means to live constantly on edge (not that the element of danger, like the risks the narrator is aware anyone runs by cruising, doesn’t also feed his excitement). For narrator and reader alike, there is the gut-clenching knowledge that this story cannot possibly end well.

Advertisement

The narrator’s complex sexual and emotional entanglement with Mitko, his awareness of Mitko’s bleak future, his own guilt over the inequality that exists between them, the shame he feels for his desire for Mitko and the tormenting hunger that draws him to the toilets where they first found each other—all this is examined with insight, delicacy, and skill. Here, in this short but rich debut, Greenwell’s talent is already plain. He writes beautiful sentences. There is no superfluous or perfunctory language, and no matter how turbulent or overwrought the content of what he is describing, the prose is always scrupulously controlled. A walk in a park one early spring day inspires feelings of freedom and elation, of being “struck somehow stupidly good for a moment at the extravagant beauty of the world,” and thoughts about lines from Whitman, whose poetry he has been teaching,

lines in which the whole world stands sharpened to an erotic point, aimed at the poet lain bare before it. They had always mildly embarrassed me…and yet it was these lines that came to me on the path in Blagoevgrad watching seeds come down like snow, that determined and defined and enriched that moment, language as always interposing itself between ourselves and what we see. What were they, these seeds, if not the wind’s soft-tickling genitals, the world’s procreant urge; and finally it felt plausible to me, his desire to be bare before that urge, his madness, as he says, to be in contact with it.

To paraphrase Isaac Babel, a writer’s story is finished not when no sentence can be added but when none can be taken away. This occurred to me when I read Mitko, for me a satisfyingly complete work, needing nothing added or taken away. The author, however, had other ideas. He turned Mitko into the first section of a new book, to which he added a second and a third part. The result, What Belongs to You, is a superb novel, wholly deserving the wide praise it received when it was published in 2016. The expansion gave Greenwell a chance to provide, in part two, material about the narrator’s earlier life, specifically his coming of age in a broken family, before taking up the thread of the Mitko story again and bringing it to its poignant and fated conclusion in part three.

From recollections prompted by the news from home that his dangerously ill, possibly dying father wishes to see him, we learn about the narrator’s relationship with that chronically adulterous, psychotically homophobic man, from whom he has long been estranged, and about a generational family history of violence and cruelty. There is also a description of his first romantic encounter with another boy, an experience that begins in pleasure only to descend into pained bewilderment before culminating in an especially twisted and heartbreaking betrayal. But however painful, this episode is nothing in comparison with what he suffers at the hands of his father and stepmother, an account of parental abuse and rejection so harrowing that, years after I first read it, the memory can still chill me.

All the same preoccupations found in What Belongs to You—love, desire, abandonment, humiliation, betrayal, self-disgust, disease, shame—reappear in Cleanness, which, if not exactly a sequel, is, Greenwell has acknowledged, part of the same literary project. Some of the stories have been published before, and I have to say that the ones I read at the time they appeared left me somewhat disappointed to see how similar the new work was to the old (according to what I’ve read about the book, I am not the only one to have had such a response). But reading the collection—or lieder cycle—as a whole offers a much different and deeper experience and has dispelled what qualms I might have had, even if I did not find Cleanness as a novel quite the equal of What Belongs to You.

Once again in the ardent, brooding consciousness of Greenwell’s narrator—the same unnamed American writer leading the same life as the protagonist of Mitko and What Belongs to You: teaching high school in Sofia, cruising the same parks and bathrooms, yearning for the love that will save him from cruising—the reader is treated to his unfailingly intelligent observations, his acute ability to describe what he sees and thinks and feels. At the heart of these stories lies a desire for radical, even ruthless self-disclosure (“the whole bent of my nature is toward confession,” confesses the narrator), and the degree of intimate detail, both physical and emotional, may at times shock readers and leave some repulsed. (Again, the thing about writing pornographically, above all when the writer appears to be talking about himself, is that there is as much chance of turning readers off as there is of turning them on.) “His only demand was to be fucked bare,” we are told about a sexual partner the narrator hooks up with through an Internet chat room, and for the narrator, you could say, this book is the literary equivalent of just that. In any case, his willingness to go to extremes in his self-exposure and self-flagellation can make it seem as though he has not only stripped himself naked for our scrutiny but flayed a layer of skin.

Advertisement

Like What Belongs to You, Cleanness is divided into three parts. Each contains three stories. Only the second part is given a title, “Loving R.,” and here we find Greenwell’s attempt to fulfill another of his goals for the composition of this book, which was to write about happiness, or, as he has said in an interview, to give some joy to his characters who elsewhere are made to suffer so much. R. the beloved is a young Portuguese man who has come to Bulgaria as part of a program for European college students and with whom the narrator has a two-year affair. In the middle story, “The Frog King,” the men go on vacation to Italy, where, among other joys, there is the freedom of behaving openly like the loving couple they are.

For all his moving and wholly convincing depictions of giddy new romance and blissful, near-religious lovemaking in “Loving R.,” the men’s happiness does not last. “I had accepted that passionate feeling faded, all my earlier experience had confirmed it, when love that seemed certain simply dissolved, on one side or both, for no particular reason, leaving little trace,” says the narrator. “But what I felt for R. was different.” As readers we are made to believe in that difference, but, in spite of it, what happens in the end is what always happens. “I love you, I said, we love each other, it should be enough, though even as I said this I knew it was unfair.” When, in our complicated relationships, is love ever enough?

In a story called “Gospodar,” the sex the narrator has—endures might be a better word—with a sadistic older man with whom he has chatted online is of a whole other kind. Set in the cheap, ugly apartment of this man, whom the narrator is meeting for the first time, it is one long, excruciatingly detailed S&M scene. Sentences lengthen Joyceanly, body parts and movements are named, but the spell does not break:

He returned his hand to my head and gripped me firmly again, still not moving, having grown very still; even his cock had softened just slightly, it was large but more giving in my mouth. And then he repeated the word I didn’t know but that I thought meant steady and suddenly my mouth was filled with warmth, bright and bitter, his urine, which I took as I had taken everything else, it was a kind of pride in me to take it. Kuchko [bitch], he said as I drank, speaking softly and soothingly, addressing me again, mnogo si dobra, you’re very good, and he said this a second time and a third before he was done.

As the second story in the collection, “Gospodar” introduces the reader early to one of Greenwell’s deepest concerns: the struggle between a person’s craving for painful, dehumanizing sex and the mortification, self-loathing, and self-despair that are its inescapable consequences.

As a counterpart to “Gospodar” there is “The Little Saint.” Symmetrically placed as the second-to-last story in the book, it too consists of one long explicit sex scene between strangers, but this time it’s the narrator who takes the punisher’s role, in obedience to the other man’s request to be made to suffer, to be fucked bare, “to be nothing but a hole.”

The middle of “The Little Saint” was the only time reading Greenwell that I ever got bored. Many years ago I worked for a (mercifully brief) time as a proofreader for a publisher of pornography—oh, excuse me, erotica—and “The Little Saint” carried me back. Able to predict more or less accurately what would be said and what would be done next (and hadn’t I just read “Gospodar”?), I could not help wishing—unfairly and even absurdly, I admit—that the narrator were doing something else.

A friend of mine once told a story about a boy he knew as a child who, having learned exactly what was involved when two people engaged in sexual intercourse, asked, How do they keep from laughing? At the beginning of “Gospodar,” the narrator mentions two moments when he might have laughed, the first being when the Bulgarian announces how he must be addressed—as Gospodar, which, in English (master, lord), strikes the narrator as somewhat ridiculous—and again when the man opens the door to his apartment “naked except for a series of leather straps that crossed his chest, serving no particular function.” In “The Little Saint,” the narrator describes the words he uses with his partner as “the language of porn that’s so ridiculous unless you’re lit up with a longing that makes it the most beautiful language in the world, full of meaning, profound.”

A mere reader, though, might find it, if not necessarily ridiculous, just the usual coarse, limited, banal language of porn. If the reader is a woman, she is likely to find confirmation of what makes so many of her gender wary of men and sex: the violence. The recklessness. The whoring. The addiction to risk. The difficulty drawing the line between consensual sex and assault, and how, when one man wants another man to feel totally humiliated and debased, to feel like the worst thing, like dirt, like less than dirt, like nothing but a hole, he calls that man she.

Ah, the sameness of it all.

“There’s no fathoming pleasure,” the narrator tells us, “the forms it takes or their sources, nothing we can imagine is beyond it; however far beyond the pale of our own desires, for someone it is the intensest desire, the key to the latch of the self.” I wouldn’t argue against such well-said wisdom. What I’ve always been highly unsure of, though, is just how much a person’s sex life defines who that person is, and how much it can really tell us—or even the person themselves—about the rest of their being. I will never be convinced, as some people apparently are, that we are most ourselves when we are in bed (indeed, it seems to me that the number of people for whom this might be true must be quite small), or that all that much can be known about a person from the way they perform, or fail to perform, the sexual act, or by their individual erotic tastes. Maybe this is partly because I have never noticed big—if any—changes in the personalities and behavior of people I know during the times when I happened to be aware they were having lots of sex and the times when I was aware they were having little or none. Nor have I seen significant differences, in other areas of their lives, between people I know who are wildly promiscuous and those who are celibate.

For Greenwell, the kinds of sexual encounters he writes about, in which sadomasochism plays an essential part, offer strong possibilities for self-discovery and self-understanding, for liberation and even salvation. His narrator, raised to believe that his desires make him worthless, foul—“a faggot,” according to his father, “which remained his word for me when for all his efforts I found myself as I am”—yearns for that moment of sexual union that will leave him “scrubbed of shame.” And not in vain: writing about his first time in bed with R., he describes how all the familiar “shame and anxiety and fear” that is almost all he has ever known of sex “simply vanished” at the sight of R.’s smile, which “poured a kind of cleanness over everything we did.”

None of this would work so well were Greenwell not entirely sincere. (Something I observed when I was working for the erotica publisher: most of the writing about gay men contained an element of sincerity, which was not true of the rest.) There is no irony in Greenwell’s writing, and—for me, regrettably—no comic touch. But one of the things I most admire is the quality of intense earnestness that marks every page. Laying himself bare, putting himself so mercilessly on the line, subjects the protagonist to the risk of appearing self-absorbed, shameful, exhibitionistic, and, of course, ridiculous. But that risk is surely part of the point: it is what makes writing like this worth doing.

Resemblances to W.G. Sebald, not just in the prose style and the tendency toward meditative reflection but in a corresponding brooding temperament, have not gone unremarked by readers of Greenwell, but I was reminded too of the enchanting, cadenced prose of V.S. Naipaul and in particular of his autofictional novel, The Enigma of Arrival. A kinship with Virginia Woolf has also been suggested, though Greenwell doesn’t revel in language the way Woolf does; he has nothing of her playfulness, and compared with her dense, luxuriantly poetic style, his own lyricism seems almost spare. Something said by Elizabeth Hardwick, however, about reading Woolf’s The Waves—“I was immensely moved by this novel when I read it recently and yet I cannot think of anything to say about it except that it is wonderful…. You can merely say over and over that it is very good, very beautiful, that when you were reading it you were happy”—captures my own similar experience reading Greenwell.

Some of the most affecting and beautiful scenes in his books have nothing to do with sexual identity or gay desire but involve exquisite observations about others whose vulnerability has touched the narrator’s heart. What Belongs to You includes a chapter describing his encounter with a charming Bulgarian boy who happens to be traveling in the same train compartment. Reflecting on his fascination with this child, the narrator says, “I felt I was watching Mitko as a boy, before he had become what he was now.” This in turn prompts the mournful observation that “any future I could imagine for him gave me something to grieve.” For if it is far too easy to imagine for the boy a life as bleak as Mitko’s—at least if he remains in “dying” Bulgaria, “where there is no future, my students tell me again and again,” and “only criminals survive”—to imagine him escaping into a better world with happier prospects gives rise to “the thought, unbearable to me, of what Mitko might have been.”

Elsewhere in the novel, while riding a crowded bus, the narrator experiences mounting concern for the fate of a trapped housefly in danger of being crushed: “It was ridiculous to care so much, I knew, it was just a fly, why should it matter; but it did matter,” for after all, he asks himself, “why should it be a question of scale?” Among the inhabitants of Sofia are many sad, neglected street dogs, and in the marvelous story that closes Cleanness, “An Evening Out”—a story as surprising in where it takes us as the pornographic stories are predictable—the narrator, unsettled by his own behavior while out drinking earlier with some former students, shares a moment of tender communion and mutual comfort with a scruffy old female stray to whom he offers shelter for the night. Each of these scenes is radiant with kindness, and, for me, reading them was like a balm. Compassion, that supreme quality in a fiction writer, is a main source of Greenwell’s power.

What kind of fiction will do for us now? In a time of unending global crises and rising despair, of climate grief and democracy grief, of Trumpschmerz and pandemic attack, a time when the overwhelming fear seems to be setting in: there where the future should be, in place of enlightened progress lie chaos and darkness—what stories do we want to write, and what do we want to read? Karl Ove Knausgaard, another writer obsessed with shame and bent on radical confession, has described reaching a point when the only kinds of literature that seemed to be meaningful were those that “just consisted of a voice, the voice of your own personality, a life, a face, a gaze you could meet. What is a work of art if not the gaze of another person?” I was happy reading Greenwell. The carefully constructed sentences, the authenticity of the voice, the clarity and deep humaneness of the gaze—all this had a soothing and uplifting effect on me, the usual effect of good literature. Coming to the end of Cleanness, I was already thinking about Greenwell’s next book, knowing that I would read anything he wrote. But when I looked up, Donald Trump was still the president of the United States.