The enchantress Circe, who could turn men into beasts with a wave of her wand—her rhabdos—wouldn’t be puzzled by the magical paraphernalia on sale today in Oxford, where pilgrims to the film locations of Harry Potter can choose from any number of wands or take home a stuffed messenger owl that might have flown from the pages of Apuleius. Magical thinking has bathed, it seems, in the Fontaine de Jouvence; it is flourishing well beyond the entertainment industry and children’s literature.

Radcliffe G. Edmonds III, in his ambitious and enthusiastic study of magic in classical antiquity, Drawing Down the Moon, brings a sensibility tuned to the revival of traditional superstitions and folk rituals. Many customs and beliefs, rooted in ancient practices of affecting reality and averting danger by acts of propitiation and protection, are being reinvented—including wayside shrines on the sites of fatal accidents. The Greeks would have recognized them: the place where a death has occurred needs to be purified, and the forces that caused it must be placated. In 1997, a shrine to Princess Diana sprang up spontaneously across from the Pont de l’Alma in Paris, above the tunnel where she died, and visitors continue to leave her ex-voto messages of hope and thanks on the ground, beside the full-size replica of the Statue of Liberty’s torch that has become identified with her.

In Drawing Down the Moon, Edmonds, who teaches classics at Bryn Mawr, roams through nearly a millennium’s worth of material, from Hesiod and Homer all the way to late antiquity and the reign of Julian, the last pagan emperor; he sweeps west to Wales and east to the Black Sea and Georgia—the full extent of the classical world. He sums up astrology and alchemy, divination and theurgy (good magic) with impressive deep reading and powers of synthesis. In a particularly lucid and authoritative chapter, he expounds the psychological meaning of the daimon, or indwelling spirit of Greek and Hellenistic thought, in contrast with the stigmatized Judeo-Christian demon or devil associated with evil. (Philip Pullman in the trilogy His Dark Materials, with his inspired invention of individual-accompanying “daemons,” has begun to restore the original sense of the word.) Nor does Edmonds overlook the many methods of scrying for signs and portents in the flight of birds, the entrails of sacrificed animals, sneezes, twitches, moles, and casting dice. It’s a work of great synoptic energy, but it is far more than a survey.

Edmonds firmly sets aside the traditional distinction between religion and magic, derived from the influential author of The Golden Bough, J.G. Frazer, who argued that religion exacts a submissive and humble approach to the godhead, imagines the end of time, and hopes for general good and personal salvation; magic, for Frazer, represented an earlier, primitive stage of humankind, as it set out to coerce the supernatural to fulfill the wishes of an individual, including inflicting harm on enemies. Instead, Edmonds argues throughout for the richness of magical knowledge systems and points out that entreating supernatural powers to grant a wish, protect a child, avoid pestilence, flood, drought, fire, and war are just as much the business of official prayers as the object of incantations.

With a definition that echoes the anthropologist Mary Douglas’s celebrated axiom about concepts of purity and pollution (“dirt is matter out of place”), Edmonds declares that “magic is a discourse pertaining to non-normative ritualized activity.” It is not so much what you do as where you do it and who you are: one person’s state religious ceremony is another’s voodoo; one woman’s high priest is another’s necromancer. (As Lewis Carroll put it in Through the Looking-Glass, “‘The question is,’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘which is to be master—that’s all.’”)

The recognition of “organic intellectuals” and “knowledge from below” has led to a profound reevaluation of mother wit and traditional wisdom of all kinds, and historians such as Carlo Ginzburg have brought sympathy and open-mindedness to the study of early modern witchcraft, heresy, and shamanism. In a similar spirit, inflected by contemporary gender and race studies, Edmonds sets out to rethink classical magic for our times and redress its reputation for ignorance and superstition. His pages on alchemy are partisan—he praises adepts as practical wise men and women, even venturing that turning copper yellow is “to produce a substance that serves for all intents and purposes as gold—or at least for the purposes of use in a ring.” And when practical benefits elude the magician or diviner, psychological effects (magic as therapy, magic as placebo) are not dismissed.

The book also differs from many earlier studies of witchcraft, astrology, and the like because Edmonds has been able to draw—and does so with relish—on rich archaeological discoveries of spells and love charms, recently unearthed in Rome from the sanctuary of Anna Perenna. According to Ovid’s Fasti, she was Dido’s sister and, in memory of Dido’s treatment at the hands of Aeneas, acted as a special protectress of wronged women. Thousands of incised amulets, curse tablets, ex votos, and other invocations, begging for her aid against false-hearted lovers and other foes, have been dug up there.

Advertisement

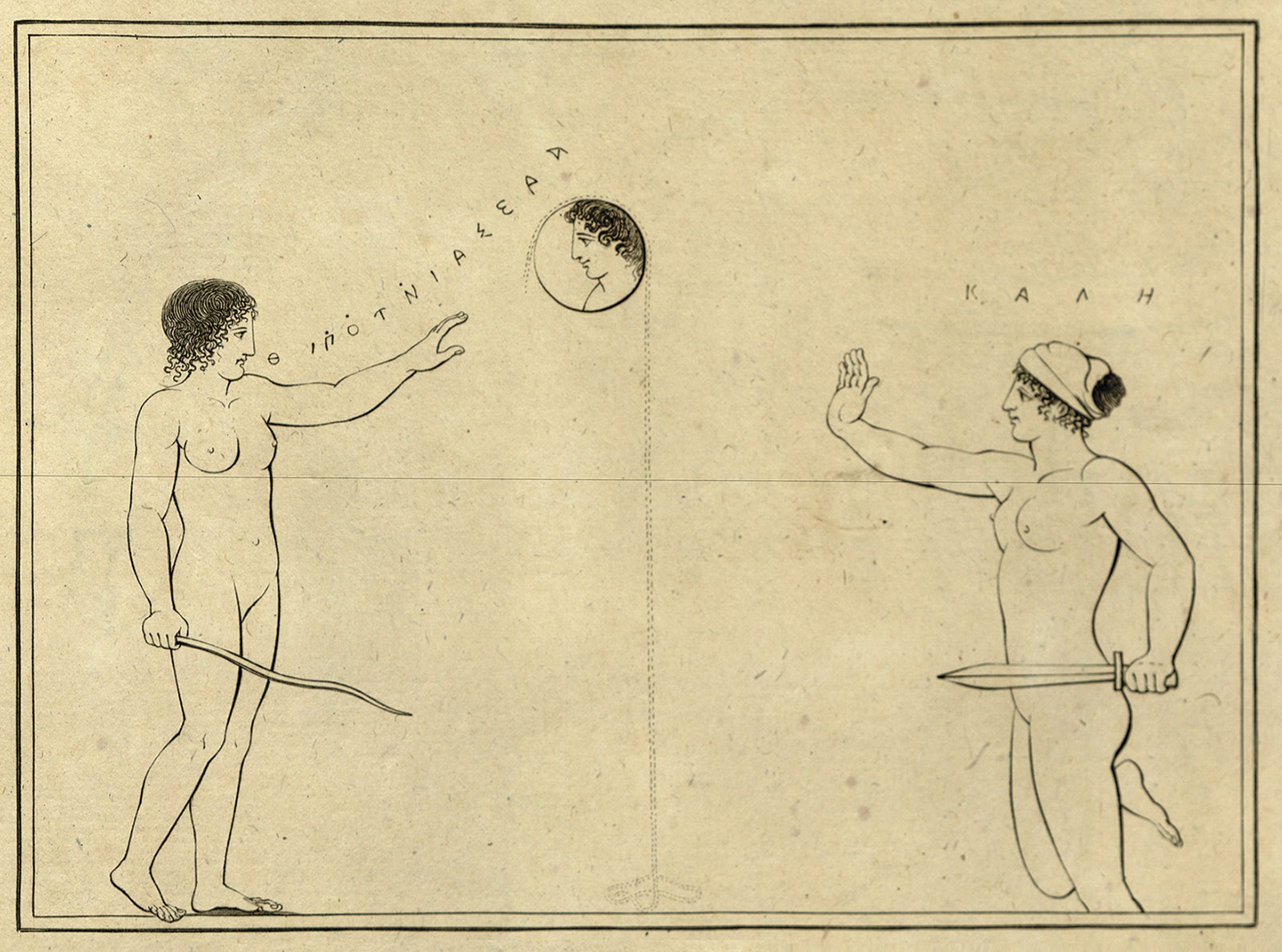

Drawing down the moon was a celebrated magical exploit—“the illicit inflaming of love”—at which Thessalian witches were especially adept. The book’s cover illustration, a line drawing from William Hamilton and Johann Tischbein’s 1791 catalog of Greek vases, shows two young women, both of them naked and on the sturdy side; one is standing and carrying a wand while the other is running with a short sword in hand, hailing the moon with the word Kale (“beautiful one”). Between them, the moon descends on a cord, like a yoyo. (The vase on which this alluring scene appeared went down in a shipwreck on its way from Naples to London; the subject remains rare in art. See illustration below.) Theocritus in a poem describes Simaetha spinning her magical instrument, the iunx, to draw down the moon, then melting a wax figure of her lover, Delphis, and ending with the cry, “O Iunx, drag this man to my house.” Her magical acts are intended to tap into lunar power, the erotic sphere under the sway of the goddess.

Edmonds also adapts from anthropology his dual theoretical approach: on the one hand, “emic,” referring to an insider’s perception, that of men and women of the time; and on the other, “etic,” referring to the analyses of classical scholars like himself, as well as historians, social scientists, and anthropologists, who interpret the past in the light of possible functions and meanings that were not known and might have been unrecognizable to the people involved (Oedipus was not aware of his Oedipus complex). To the ancient Greeks, Circe the enchantress is the daughter of Helios the sun and a figure of profound wisdom who can give Odysseus reliable instructions about going to the world of the dead and back; she may be an intermediate figure, who could be dangerous but choose to be benevolent, too, as she is, ultimately, to Odysseus. By contrast, for later, nonpagan readers of Homer since the Middle Ages, her metamorphic powers over nature (such as when she changes Odysseus’s companions into swine), her irresistible seductiveness, and her knowledge of the underworld mark her as evil, even diabolical.

These features are bound up with wary, pejorative Greek ideas about femaleness, as is also the case with Medea—Circe’s niece, as it happens, who is so polluted by her crimes that when, in the Argonautica, she entreats Circe to purify her, Circe admits that her powers are too weak. In postclassical times, Circe generates a line of avatars, both imaginary and real—“the foul witch Sycorax” in The Tempest even echoes her name, and the Weird Sisters in Macbeth are cast in this mould. But the mythological fantasies leaked, fatally, into reality, and the often indigent, powerless targets of European witch-hunts were stigmatized as malignant sorceresses, tortured, and killed.

Frequently, magical knowledge is presented as foreign, originating on an exotic periphery or in an ambiguous zone. For example, ever since Herodotus, ancient Egypt has been perceived as the supreme fountainhead of secret knowledge and enchantments, its wisdom evoked in support of attempts to bless or curse, to defy time and mortality. Thessaly and Persia were also sources of esoteric and often suspect learning (the magi in the Gospel of Matthew reflect this legacy, as do the evil Zoroastrian enchanters in the 1,001 Nights). When Dido, queen of Carthage, is building her funeral pyre, she consults a wise woman from beyond the Pillars of Hercules and the known world; in The Aeneid, Virgil evokes this priestess in lurid imagery:

She’d sprinkled water, simulating the springs of hell,

and gathered potent herbs, reaped with bronze sickles

under the moonlight, dripping their milky black poison,

and fetched a love-charm ripped from a foal’s brow,

just born, before the mother could gnaw it off.

Magic also takes place not in temples or public assemblies but in ambiguous interstitial spaces—cells, underground passages, deep wells, middens, and dark corners. Improvised, impermanent, and clandestine settings emerge as the most hospitable for magical acts, and an aura of the illicit and the pleasures of deviancy hang around them. Because magical operations tend to be private and take place discreetly, out of sight of others, they’re practiced on the margins—which then demarcated women, slaves, and children. A large cache known as the Greek Magical Papyri, another recent find in the temple of Sulis Minerva in Bath, England, as well as the hoard in the shrine of Anna Perenna, testify abundantly to the lively practice of magical rites among “the non-elites,” Edmonds writes,

Advertisement

whose expressions were never preserved and recopied throughout the millennia of reception of classical materials. In the curses scrawled on sheets of lead, seeking to restrain rivals in business, law courts, athletics, or erotic affairs, we can see the hopes and fears of a group of people whose voices have been lost in the intervening centuries.

The Greek Magical Papyri were written in Egypt in Hellenistic times, from the third century BCE into the Christian era; the documents have been gradually emerging since their first discovery in the seventeenth century and are still being deciphered and translated. The work is arduous, but this remarkable resource has thrown a different light on the everyday life of the inhabitants of the late-antique world as it was being fused with Christianity and, not long afterward, with Islam. Curses and spells, amulets and secret formulas fill these magical writings, and the evidence they give of the busy activity in this field is corroborated by engraved magical gems, tablets, and charms farther west along the coast of North Africa and also in the eastern Mediterranean. The Bath site yielded hundreds of curse tablets, chiefly calling for revenge on petty thieves. These anathemata are chilling: often inscribed on lead, pierced with a stake or a nail through the center, they were buried or dropped down a well.

With the help of magus-like work by scholars such as Christopher Faraone, Esther Eidinow, Roy Kotansky, and Sarah Iles Johnston, Edmonds also explores the inscriptions on the silver lamellae, or tiny scrolls of silver, that were rolled up into small phylacteries and worn for protection. Again, the procedure gains force from intimacy: amulets are worn next to the skin, under one’s clothes, and kept invisible, thus tightening the pact between the daimonic powers invoked and the petitioner. The more elaborate the magic formula and process, the more efficacious the spell—in whatever medium. One of my own favorites, quoted by Richard Kieckhefer in Magic in the Middle Ages (1989), comes from the Greek Magical Papyri (Number XVI): to know the secrets of a certain woman’s dreams, the petitioner “takes a strip of hieratic papyrus, inscribes it with powerful names and characters, wraps it around a hoopoe’s heart that has been marinated in myrrh,” and then tucks it in next to her sleeping body.

As Edmonds explains, ritual acts often depend on principles of association: the myrrh is redolent of the longed-for lover’s erotic allure; curses inscribed on lead tablets convey the worthlessness, the weight, the chilly deadness of that element; the drawn-down moon kindles nocturnal passions. The ritual object is activated by incantations, and verbal formulas are key to this process of unlocking the latent powers, whether for an Egyptian mother hoping her child will recover from fever, or a Thessalian sorceress performing a rite to bind the moon to bring about what she—or her client—desires.

The strongest sections of Edmonds’s book arise from his discussion of the role of words, especially the voces magicae, or nonsense rigmaroles (abracadabra being the most familiar), that were invented and repeated to make an enchantment take. Such potent nonsense formulas in antiquity were also organized in pyramids (both inverted and upright), in seals, and in magical squares. The ritual use of these formulas continued strongly in Islam, with beautiful calligraphically patterned talismanic shirts made to protect children from harm. Such talismans strive toward the “high coefficient of weirdness” that the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski diagnosed as the essence of magic: the supernatural is invoked by the names of remote, unpronounceable forces, and the spells stack up jumbles of harsh consonants (Xs and Zs predominate), making for bamboozling babble, gobbledegook, and jiggery-pokery (these would all become features of Christian devils and devil-worship).

Magic depends on forging beyond the boundaries known to reason; not exactly aiming to be irrational, it does seek to go beyond the comprehensible into the ineffable and unknowable. The term “hocus pocus” comes from the priest’s words Hoc est corpus, pronounced to effect the transubstantiation of the bread and wine into Christ’s body and blood in the Catholic Mass. As Edmonds points out, early Protestants attacked the papists for practicing magic, peddling superstitions, and securing divine favor through the wearing of amulet-like medals and scapulars, formulaic repetition of prayers (the rosary), and the sale of indulgences.

One weird and wonderful device from antiquity that has not (yet) been revived enacts a pun: the iynx (or “iunx”) that Simaetha uses in Theocritus’s poem was named after the nymph—an Oread—who enrages Hera because she helped her husband Zeus seduce the nymph Io. In revenge, Hera turns Iynx into a “maddening bird,” called a “wryneck” because it keeps twisting its head; according to the typical ironies of myth, the penalty inverts the crime—Iynx’s eloquence brings her to eternal torment by strangling her voice. Later poets added to the story, describing how Aphrodite impales the wryneck on a four-spoked wheel and then gives this sinister, newfangled snare to Jason to enthrall Medea, and thereby incites her to betray her father and country. Was a real bird fixed to the wheel? The classicist Sarah Iles Johnston does not believe so, since in existing vase paintings of the strange device, no bird appears; instead, the iunx looks like a dreamcatcher or, as Edmonds suggests, a child’s whirligig—and he gives every sign of having tried one out (sans dead bird). In its effects—a hypnotizing whirling and humming—the iunx shares features with the Buddhist prayer wheel or the Egyptian sistrum, or even with maddening modern instruments such as bull roarers or vuvuzelas.

Iles Johnston underlines how the spinning and humming evokes the nymph’s voice and its erotic powers, pointing out the nymph’s parentage: in one version, Iynx’s mother is Peitho (Persuasion) and her father Pan, the inventor of the flute (or syrinx). Magic, following this line of thought, depends on sound, music both verbal and nonverbal; ultimately, it becomes a form of speech, grounded not in supernatural belief but in the imaginative power of human language.

The extreme complexity of most spells meant that failure could always be blamed on the flawed execution of at least one of the elaborate steps, or the imperfection of an ingredient in the brew. To make magic ink, for instance, you need “myrrh troglitis, four drams; three karian figs, seven pits of Nikolaus dates, seven dried pinecones, seven piths of the single-stemmed wormwood, seven wings of the Hermaic ibis, spring water.” Burn them together and write the spell with the results (beware if your wormwood be double-stemmed!). The tongue-twisting formulas also seem designed to fail, as they defy memorizing, or even copying with accuracy. One spell requires you to number every part of the target’s body: “Malcius the son of Nicona, his eyes, hands, fingers, arms, nails, hair…[etc.]; in these tablets I bind his business profits and health.” Fairy tales and myths often turn on the one thing that is fatally overlooked: the heel in the case of Achilles’ bath in the waters of Styx. The spread of literacy, however, rendered it possible to fix spells more securely and circulate the formulas more widely. Edmonds quotes Jonathan Smith, who noted that “the chief ritual activity within the Greek Magical Papyri appears to be the act of writing itself.”

Imagery of binding, knotting, pinning down, and securing by means of constraints of every kind suffuses magical procedures in the ancient past; the word “fascination,” from fasces (bundle), also implies making fast—lashing disparate elements together into one body. The evil eye exercises the power of fascination, immobilizing and subjecting its target to the beholder’s gaze. As Edmonds describes, the Platonist mode of vision presupposed that the onlooker radiated beams of light onto objects in order to see them; in this model, a look is active and therefore potent—for good and ill. On marriage belts, jewelry, seals, gems, and documents, this metaphor of binding takes exquisite forms, in gold filigree or elaborate illuminations, as the seeker tries to hold on to a beloved and secure his potency, her fertility, their eternal passion. The same web of fastening metaphors finds a verbal equivalent in those riddling rhymes and intricate palindromes of magic words. The hoped-for effects envisage staying or fixing the future: knotting or binding the unknown into a state from which it can’t disengage.

It is striking how the practices and belief structures that Edmonds describes continued—and continue. Ernesto de Martino, working in southern Italy (former Magna Graecia) in the l950s, found fear of the evil eye still very real, and the measures taken to ward it off involve a wise woman or man casting sympathetic spells. Similarly, the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, in its “Magic and Superstition” collections, includes figures stuck with pins and other horrible curses that were made and concealed in the targets’ houses in modern times—in England.

At the close of his study, Edmonds comes full-circle to stress the power of the word, not only in magical processes but in the very understanding of what magic is. In an effective chapter on the power and importance of labeling, in relation to oneself and others, he brings to bear developments in thinking about abuse and hate speech. Acts of naming are forms of conjuration, in effect, and define who is seen as a magician or a magus, a sorcerer or a witch; who is respected or despised; who belongs in normative social spaces and who is relegated. Naming defines what is seen as philosophy and metaphysics, or denounced as heterodoxy and even, as it was later to be called, Satanism.

Apuleius of Madaura, the second-century philosopher and author, takes to the stand here as Edmonds’s star witness. Apuleius was born in present-day Libya, lived in Egypt, wrote in Latin, and eventually became a priest of Isis; his extraordinary, mystical, comic romance The Metamorphoses of Lucius, or The Golden Ass features many scenes of witchcraft, including the dread necrophiliac witch Pamphile, who changes shape and flies out of the window as an owl. The hero-narrator turns into a donkey after misapplying one of Pamphile’s magic ointments, which he thought would give him wings.

In a remarkable case of imagination impinging on reality, Apuleius was himself charged with witchcraft and brought to trial. He had married in the provincial town of Oea a rich widow older than himself; her relations accused Apuleius of foul play. His speech in his defense, which he wrote down after he was successfully acquitted, has survived. Edmonds reads this uniquely revealing statement as clever, even casuistic, turning the tables through labeling and self-labeling. The accused Apuleius denies nothing, but he redefines his acts—as philosophical research, medical remedies, and so forth. He presents himself as a sophisticated scholar from the metropole, and ridicules and shames his wife’s relatives as credulous provincial bumpkins fearful of malignant spells.

For this reason, I’m not convinced that present-day understanding of realized metaphors breaks with the ancients’: the important, ethical emphasis on the need for justice in naming, the ideals of fair speech rather than foul (“hate speech”), recognize the powers of language to conjure real effects, while in modern literature—in the work of writers as varied as Jorge Luis Borges, Seamus Heaney, and Jeanette Winterson—magical transformations of experience are staged in a secular spirit; they harness language’s active powers, but do not presume divine presences or call on supernatural forces.

Drawing Down the Moon calms traditional anxiety about magic and rejects censure, avoiding calling certain rituals or beliefs superstitions, with the effect, at times, of seeming almost too easygoing. As a classicist, Edmonds takes readers up close to experience the rituals and artifacts through the participants’ eyes; as a twenty-first-century citizen he avoids hierarchical discriminations between metaphysics, philosophy, religion, and magic. But he makes no attempt to mount a literary or aesthetic case for magic as imagination, as allegory and dream. He perhaps assumes too easily that magic was believed by its practitioners, and shows little interest in the complex pleasures magical representations and stories can give to the skeptical and dissenting.