In February, Tomiekia Johnson’s mother, father, sister, and daughter came to Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF), a state prison in the small city of Chowchilla, for their monthly visit. Tomiekia had been reading the news about the spread of the coronavirus and told her family to prepare for catastrophe. “They were…unmoved,” she wrote to me in August. “They gave me the side eye. Now here we are.”

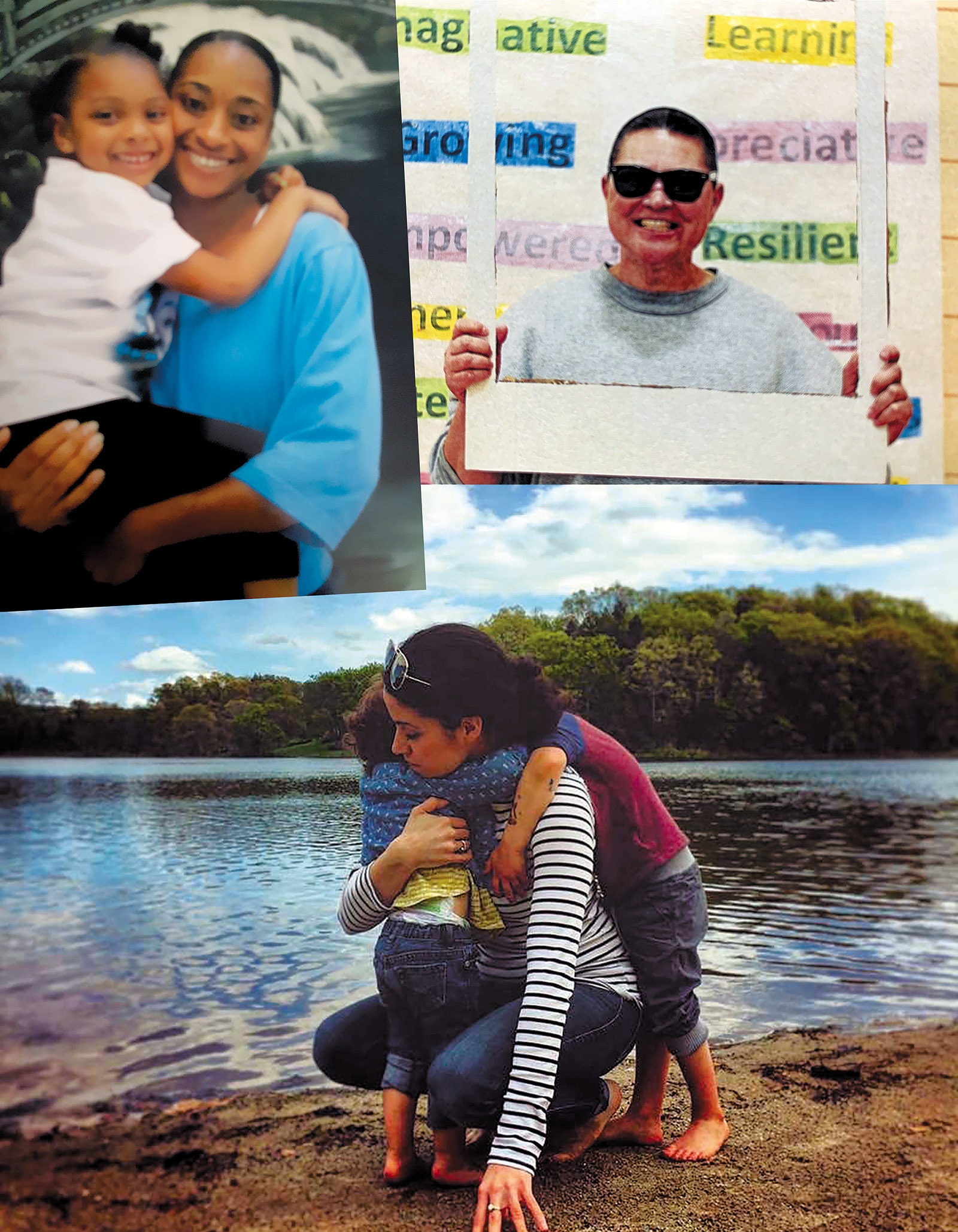

On March 16, visits to the facility were paused. Tomiekia, who is forty-one, and her thirteen-year-old daughter had to make do with phone calls, punctuating their brief, monitored conversations with expressions of reassurance and affection: “You know I love you, right?” “Yeah, mama, I know.” In early April, a prison nurse tested positive, Tomiekia told me, which resulted in a brief quarantine of certain units. Hand sanitizer and disinfectant spray were made available on demand, but the CCWF population, which tops two thousand, still mingled on the parched grass yards of the sprawling compound.

Then, Tomiekia wrote, “people started to realize they could die here before making it home.” Panic set in. Women inside began to talk about lawsuits, anarchy, and escape plans. Tomiekia counseled others and thumped her Bible. She saw the virus, she told me, as yet another challenge—after the domestic violence she had suffered, the killing of her husband that she maintained was an accident, the loss of her career and every material possession, the trial during which she saw her character demolished, the separation from her child. “We’re being tested to the ends of our being,” she told me. “To the last threads of our might.”

Joe Vanderford, a transgender man at Minnesota’s Shakopee Prison for women in the southeastern city of Shakopee, was accustomed to feeling unmoored, a self-described “castaway.” Joe, now fifty-three, had been abused and neglected as a child. Over his thirty-three years in prison for murder, he has spent a total of eight in solitary confinement, including one five-year stretch. During his time in “the hole,” he caught and trained a baby mouse, which slept by his head in an empty Folgers jar, until one night he accidentally squished it. “I guess surviving loneliness and punishment is my great accomplishment and shame,” he wrote. When the coronavirus began to circulate, Joe advocated for masks. “We have zero death row inmates,” he wrote me, but with Covid spreading, “each prison is death row.”

Nicole “Nikki” Addimando, a thirty-one-year-old former preschool teacher, was a new arrival at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, New York’s only maximum-security women’s prison. “Being in here during this pandemic is bizarre,” she wrote me in late March. As in California, visits had been suspended, and Nikki did not know when she would see her five-year-old daughter and seven-year-old son again. When she was in county jail, they had seen one another every week for an hour. But once Nikki was transferred to Bedford Hills in February, she hoped for longer visits: the prison had a playroom, and children were allowed to stay for an entire day. Instead, everything shut down. “More isolation,” Nikki wrote. “Further removed from the world and what’s going on outside of these barbed wire fences.” Some mornings, she looked up at the moon as she walked across the grounds, and it reminded her that she was “still on this earth. But I feel a million miles away.”

On March 10, the day before the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic, I rented a car to visit Bedford Hills, some forty miles north of Manhattan. The radio buzzed with talk of Chinese cities shutting down, Italians lying in hospital hallways, infected cruise ships. That day, Governor Andrew Cuomo had ordered a “containment zone” around a suburb about thirty miles south of the prison. I wiped the car down with bleach before I got in. But at Bedford Hills I saw no precautions, other than some posted signs recommending hand-washing and listing symptoms, such as fever and cough.

I was there to see a woman I’d been corresponding with, a young mother. She had been ordered to clean a trailer where a visitor from a county with an outbreak had spent time, she said, shrugging. Had she been provided any protective equipment, I asked—gloves, maybe? She shook her head. “Wash your hands really well,” I counseled, but she was confined, along with dozens of others, to a communal unit with a shared bathroom, usually thick with cigarette smoke. After visitation ended, she had to undergo a routine strip search. I walked to the parking lot. There was a shift change. I followed the guards through the gates, bare hand after bare hand pressing against steel.

Advertisement

The virus may have already been circulating inside. Though the first case was reported in New York on March 1, epidemiologists now think there were already thousands of cases in hotspots. Two incarcerated women with whom I communicated believe the infection was introduced into Bedford Hills by a civilian commissary employee who, coughing, dispensed shrimp noodles and tampons, Kit Kats and toothpaste. Typically, after their shifts, commissary workers met up with friends on the yard, moved in and out of their units, the chapel, the cafeteria. People in women’s prisons share food, makeup, clothing; fight, talk, and hold each other for comfort or for romance. Within ten days of my visit, Bedford Hills was closed to visitors, and all nonessential businesses statewide were shuttered.

Over 230,000 women and girls are held in US correctional facilities, a more than 750 percent increase since 1980. As of 2017, Black women were incarcerated at nearly twice the rate of white women. Women who identify as lesbian or bisexual are represented in jails and prisons at a proportion that is eight to ten times greater than in the US population. Incarcerated transgender people can be housed based on the sex they were assigned at birth and not their gender identity, which proves especially harmful for trans women held in men’s facilities. According to one study, incarcerated trans people are sexually victimized at rates nearly ten times those for incarcerated people in general.

Eighty percent of incarcerated women are mothers. As of 2016, more than five million children in the US had at some point had a parent in prison. A child’s risk of entering the foster care system, already high when a father is incarcerated, soars when a mother, often the primary caretaker, is detained.

I have spent nearly two years corresponding with hundreds of people held in women’s facilities across the nation to understand their pathways into the criminal legal system. Soon after my trip to Bedford Hills, I began checking in with incarcerated people I knew and reaching out to others to track how they were affected by the coronavirus. I sent messages mainly through Aventiv or Global TelLink, leaders in the $1.2 billion correctional telecom market. Messages, which are limited in length, can cost up to forty cents each to send—rates that are especially unaffordable to those in prison, who are either forced to work for free or else paid wages that, in some states, start at four cents an hour.

In many prisons, censors scan every correspondence going in and out of the institution. Of the thousands of letters and e-mails I have sent to incarcerated people since 2018, some disappeared entirely or arrived weeks late. I was never alerted when one was rejected. The listed rules were vague: messages judged to threaten the “order of the institution” or impede a person’s “rehabilitation” could be blocked. Still, between March and September 2020, I corresponded with eighty-eight people in twenty-six women’s prisons in nineteen states, received over six hundred e-mails and twenty-five letters, and conducted twenty-one phone interviews. Almost everyone responded. They wrote, called, and wrote again. The writing itself seemed to carry urgency.

Because conversations about mass incarceration usually focus on the more than two million men behind bars, women in prisons are especially marginalized. A 2020 US Civil Rights Commission report found that women face harsher treatment and restrictions because the system does not adequately take into account gender differences, and that sexual violence committed by staff is pervasive. Prisons may not provide enough sanitary products during a woman’s period. Just under half of US states permit women to be restricted or shackled during childbirth.

The coronavirus has made those in women’s prisons still more vulnerable. “The world at large has forgotten us,” one woman wrote from Texas. “We are the most disempowered and despised population,” another wrote from Arizona. A woman in Kansas reported that within weeks of the declaration of a pandemic, ten body bags were delivered to the prison: “Guess we will not be going to the hospital if it comes here.”

When the coronavirus began to spread, doctors, health officials, advocates, and attorneys appealed to governors and public officials to issue broad releases from prisons and jails, especially for incarcerated people who were fifty or older, pregnant, or in ill health. On March 16, Dr. Amanda Klonsky, a prison educator, wrote a New York Times op-ed laying out essential steps for handling the pandemic in detention facilities, which included the release of elderly or infirm people, a general reduction in jail populations, staff training on the prevention of transmission, widespread testing, and quality medical care for the ill. “To do anything less than all of this—out of hate, apathy, or spite—will endanger us all,” she wrote.

Advertisement

On March 27, Cuomo ordered the release of up to 1,100 people held in jails, where individuals are often detained before trial. Still, throughout the spring, Rikers Island Jail in New York City—called “the epicenter of the epicenter” by the president of the corrections officers’ union—was a den of the virus. In an affidavit, a Rikers Island social worker swore that officers were brought in daily in buses that were never wiped down and that they disregarded social distancing and mask guidelines. Her incarcerated patients wore “dirty or torn masks,” and hand sanitizer and soap dispensers sat empty. Those who drafted policies, the social worker noted, worked from home, “safe and sound and far from the reality of the situation…. Perhaps that is why the execution and enforcement of these protocols remain aspirational and so blatantly estranged from what is happening on the ground.”

Approximately 90,000 people are behind bars in New York State. And while some jails across the country saw a decrease in populations—due largely to decisions made by local authorities—most prison populations barely budged. This is because when public officials granted early discharge, it was often for people who met specific criteria, largely those with nonviolent offenses who were nearing their release date. Cuomo, for example, decreed that pregnant women with fewer than six months left could be released: eight were eligible.

The fixation on “nonviolent criminals” was politically shrewd, since the public is generally opposed to the liberation of people they perceive as dangerous. But seen as part of the larger conversation on mass incarceration, it made little sense. “That narrative of the nonviolent offender is disconnected from medical and criminological truths,” Nazgol Ghandnoosh, a senior analyst at the Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy organization focused on reducing incarceration, told me. “We know older people are especially at risk of Covid, and because of lengthy sentencing, most older people in prison were convicted of violent crimes long ago. We also know that when they are released, these individuals pose some of the lowest safety risks to our communities.”

Roughly 20 percent of women incarcerated in the United States have been convicted of a violent crime. Five percent have been convicted of murder. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, a criminal justice reform organization, up to 88 percent of women in prison were abused prior to incarceration. “I have yet to meet a person who hasn’t been physically or sexually abused,” Kwaneta Harris wrote me. She is serving fifty years to life in Texas for killing a boyfriend she says assaulted her. Like Kwaneta, many women convicted of murder killed an intimate partner or family member; in many cases, that person had physically harmed them.

In my research, I have found that the vast majority of such women were failed by the system that later condemned them. Lisa Jackson, for example, lives in Kwaneta’s unit. She wrote me that when she was twelve years old, she reported to the police that she had been beaten and raped. In court, she wrote, she was deemed “unreliable” because she had been involved in fights at school and took psychiatric medication. The case was dismissed, and the perpetrator walked free. Years later, as a single mother struggling with substance abuse, Lisa received a twenty-year sentence for robbery.

As the summer dragged on, temperatures in Texas rose above 105 degrees, and Lisa and Kwaneta began to bathe with soap and water warmed in electric kettles to avoid contact with guards and communal showers. Lisa had an underlying health condition. “I am living my worst fear,” she wrote. “To die in prison.” By early September, the Texas Department of Criminal Justice reported 20,647 Covid cases and up to 186 deaths in the incarcerated population.

“The tragedies we suffered as little girls and young women groomed and doomed us to this current state of modernized slavery,” wrote Sandra Brown, a forty-eight-year-old Black woman serving twenty-two years in Illinois for a killing she says was in self-defense. “I have been the recipient of acts of violence since I was a child, and the law was virtually nowhere to be found. But the one time I fight back because I am afraid for my life, I am now a ‘violent offender.’”

Nikki at Bedford Hills testified in court that she was raped at five. The rapist abused others and eventually moved to Florida. As an adult, Nikki was assaulted by her partner, who tortured her, including sexually, for years. In 2017 Child Protective Services checked on the family after an anonymous caller reported that “on a weekly basis, the mother has had visible bruises to her face and chest.” According to Nikki’s testimony, following the CPS visit, her partner forced her to have sex and pulled a gun on her. They struggled and she gained control of the weapon. He threatened to kill her and himself, which would orphan their children. “I took one step and I lunged and I pulled the trigger,” she testified. “I was thinking if it didn’t go off, I was gonna be dead anyway.”

Before the killing, multiple state agencies had identified or assessed Nikki as a victim: CPS had visited less than a day before the shooting; the district attorney’s office and two police departments investigated attacks on her; she received counseling at a victims’ services agency and an organization for domestic violence survivors; two state-certified forensic nurses at the local hospital recorded and photographed her injuries after rapes and beatings. Following the shooting, medical records and graphic images of Nikki’s abuse were entered into evidence. But a prosecutor told the court that Nikki was a “master manipulator” who may have “self-inflicted” vaginal prolapses, burns, and deep bruises. The judge stated that Nikki may have “reluctantly consented” to sex acts, found her ineligible for a law intended to lessen the terms of some domestic violence survivors, and sentenced her to nineteen years to life.

Tomiekia, in California, had worked as a 911 operator and then graduated at the top of her police academy class before becoming a California Highway Patrol officer. She was a bowling league champion and a devout churchgoer. When her husband beat her, she told no one; she was ashamed. In 2009 Tomiekia reported that her husband attacked her and that, as they both groped for a gun in her purse, she shot him in what she insists was an accident. After her conviction, her bewildered father told reporters, “She overcame all the obstacles that a Black person can overcome.”

Tomiekia regretted pursuing a career in law enforcement. Officers who shoot unarmed Black civilians are often defended by their colleagues, prosecutors can decline to bring charges, and grand juries rarely indict. In contrast, Tomiekia wrote me, she went from “beloved poster child to enemy number one…quick as Superman’s outfit change in a phonebooth.” She felt ostracized at work, a prosecutor spent years building a case against her, and a judge handed her two life sentences. “I wish I had known the system is a colonist pipeline that preys on the weakest, poorest, underserved, undereducated, marginalized people, mostly Black, in America,” she wrote. “I was working as a first contact of the pipeline while simultaneously the demographic it was designed to imprison.”

Joe Vanderford was designated female at birth, and the state of Minnesota calls him by the name on his birth certificate. He says he was sexually assaulted by his father and another family member from the time he was a young child. “That is why my insides are screwed up (not just emotional),” Joe wrote me. “They gave me beer and surprisingly didn’t kill me with penetration.” Joe says he also saw his father beat his mother, a Thai immigrant. His father later shot himself outside Joe’s childhood home.

In 1987 Joe—nineteen years old, pregnant, and suicidal—killed an ex-boyfriend he felt had abandoned him. Despite having learned of Joe’s difficult childhood, a foreman said the jury could find no “mercy,” and a judge sentenced him to life in prison. Joe has developed painful arthritis. He has expressed deep remorse, taken college classes, published short fiction and poetry, and worked as a facility baker. On Mother’s Day this year, saddened that the women at Shakopee could not celebrate with their children, he made fifteen pans of apple crisp and wrangled permission to add pink whipped cream as a special touch. “It took two extra hours to put the cream in tiny cups,” he wrote me. “If you don’t portion control, it’s a dormant riot.” The parole board has denied him release four times, but he plans to try again in October.

As the coronavirus spread, conditions in prisons, already dismal, began to deteriorate further. Each correctional department came up with its own policies, but infections were inevitable because jails and prisons create the very conditions that fan the spread of a virus. “Incarcerated people were sentenced to the care and custody of the state, but the state does not have a plan to care for them while in custody,” said DeAnna Hoskins, the president of JustLeadershipUSA, an advocacy organization focused on lowering the number of people in prisons and jails. “This population is thrown away.”

Normally classes, religious gatherings, exercise regimens, jobs, volunteer-led programs, and visits with loved ones help incarcerated people organize their days, prepare to rejoin society, and cope with the mental illness that afflicts more than half the population. With the onset of the pandemic, nearly everything stopped. In Pennsylvania, some people received coloring books to pass the time.

Food quality declined, women told me, and commissaries were decimated. Chow halls closed, and bag lunches were delivered: “One peanut butter and jelly sandwich with sour macaroni salad” for dinner in Pennsylvania, a “hard hot dog weenie” in Texas, “expired milk” in Kansas. In Florida, women took pills they got on the black market to sleep the days away. In South Carolina, a woman reported that a “girl from my living quarters tried to kill herself…she carved into her chest and with blood smeared ‘I love you’ on a wall…. I’m glad I practice mindfulness meditation.”

The lockdowns meant that people were closed in their units—and sometimes in their cramped cells—for as much as twenty-three hours a day for weeks or months at a time. In their free hour, they often had to choose whether to stand in line for the showers or the phones. In Florida, one woman wrote that the “stress is so high that you can almost see it when you walk through the door.” In Pennsylvania, a thirty-eight-year-old woman who had never before received a disciplinary offense told an officer who woke her with a flashlight, “I’m gonna take that light and put it in your ass.” In New York, one woman hit another with a hot pot during a dispute over soggy cereal. “If this wasn’t real, it’d be funny,” wrote a witness to the incident, who watched as both victim and assailant were led away. They soon returned: solitary was full.

During the pandemic, the number of individuals in solitary or lockdown rose from 60,000 to 300,000 in about one month. Across the country, prisons used solitary—cells normally reserved for punishment and security (and unofficially for retribution and mental illness management)—as a form of medical isolation. At Shakopee, an incarcerated woman named Elizabeth Hawes told me that guards escorted a friend of hers, an eighty-seven-year-old woman nicknamed Grandma, to a segregated cell, ostensibly for her own protection. Though Grandma had not broken any rules, guards did not allow her any belongings. “They didn’t let her bring her tablet, which she likes to play games on,” Elizabeth told me, near tears. “There’s no TV there. It’s cold up there.” Nicholas Kimball, communications director of the Minnesota Department of Corrections, wrote to me that “it’s certainly possible something happened in a way that it shouldn’t have early on. But medical isolation for Covid protection is not a punishment and isn’t viewed that way by our agency.”

Schwanika Patterson, a twenty-nine-year-old at Bedford Hills on a burglary conviction, said that her time locked away while battling Covid was “the worst thing I ever went through in my life.” She worked at the commissary where women told me that a civilian had come to work sick in March. In early April, Schwanika began to have trouble breathing. She asked an officer to take her to the medical unit. “He called at least seventeen times,” she said, but nobody picked up. Eventually, Schwanika was escorted to see a nurse, given a breathing treatment for asthma, and sent back to the sixty-cell unit.

Two days later, Schwanika described her head aching, her ribs “closing in, making a fist, like my bones intertwined.” She was swabbed for Covid and placed in a remote room, without her tablet, pen, paper, phone access, or soap: “I felt like I was dying, and nobody was helping me.” She received a positive test result and, after five days, kicked at the door until, to her surprise, it swung open. Once in the hall, she sank to the floor. A sergeant approached and knelt down beside her. “I miss my mom,” Schwanika told him. The sergeant arranged for her to get her tablet and some soap, and to make a call. Later, Schwanika told me, he fell ill, too. By September, more than 25,000 correctional workers nationwide had tested positive.

In April, Darlene “Lulu” Benson-Seay became the first woman to die of Covid-19 in New York State custody. Lulu was incarcerated at Bedford Hills for killing her abusive partner. She was sixty-one, recovering from open heart surgery, and working on her commutation application. When she fell ill, she hid her symptoms, scared to be taken somewhere strange. “It is just a little cold,” she wrote to her sister on April 5. Two days later, she was transferred to the hospital. On April 28, after doctors determined she had no chance of recovery, she was removed from a ventilator. Before Lulu died, her sister asked a doctor to arrange a video call so she could see her one last time. A prison guard stationed outside the room would not allow it.

The experience of incarceration itself can sicken people. Tabitha Maynard, who has been in Michigan’s Women’s Huron Valley Correctional Facility for nearly two decades for killing her sexually abusive father, wrote that the prison health care center had been nicknamed “death care” long before the pandemic. The facility saw multiple outbreaks of scabies. In April one woman from Huron Valley messaged me about Covid symptoms and then stopped responding. Twenty days later, she wrote that she had tested positive and been moved with others to what she called a “warehouse,” with two portable showers. “We was on our own,” she wrote. “Anything we need, we had to write down and put in a milk crate. No one would step foot in the building.” Chris Gautz, the public information officer for the Michigan Department of Corrections, wrote that “it would not be true that prisoners were left in a room alone unattended.”

In early May Krystal Clark, a mother of four serving seventeen to thirty years for driving a car during an armed robbery, called me from Huron Valley, coughing sharply and crying. It wasn’t Covid-19, she said, but chronic illnesses of the heart and lungs that were exacerbated by a lack of medical care and black mold. If you peered up through a missing ceiling panel, others at the facility confirmed, you could see a dark, thick, gooey substance growing inside the walls, the same substance that coated the showers, so profuse that tiles peeled up and bricks disintegrated. After a decade inside, Krystal slept sitting up in order to breathe. A message from the administration e-mailed to the Huron Valley population told them to inform “healthcare if you have symptoms or are feeling sick. Or if you see someone else with symptoms.” But when Krystal, who was kept in a two-person cell, told an officer that her new cellmate had “no sense of taste or smell,” she wrote me, he told her not to “bother him with that bullshit.”

The rules of social distancing clashed with the reality of prison, which allowed for arbitrary regulation. In New York, a woman wrote that one day she and other prisoners were written up for covering their faces, using masks fashioned from pantyliners and rubber bands. The next day, they were required to cover their faces and, since the shipment of state-issued masks had not arrived, were encouraged to craft their own, out of, for example, pantyliners and rubber bands. In California, a woman reported that incarcerated essential workers, including those who cleaned medical and quarantine areas with Covid-positive patients, shared rooms, sinks, toilets, and showers with others. In Texas, where infection rates soared over the summer, two women in separate housing units independently reported that staff and incarcerated people alike refused to wear masks, claiming to be “protected by the Blood of Jesus.”

The majority of people who wrote to me remarked on the absurdity of trying to enforce social distancing in a prison. On March 25 at Florida Women’s Reception Center (FWRC), Kristen Wagner reported that people were marched at a six-foot distance to a chow hall, yelled at to sit on every other seat, threatened with pepper spray, and then marched back to their dorms, where they slept two feet from their bunkmates. “What is administration thinking? That we can only contract the virus from each other while we eat? This is the kind of incompetence that’s going to kill us.” By early September, at FWRC, at least one incarcerated woman had died of Covid-19 and 484 had tested positive.

In Missouri’s Chillicothe Correctional Center, Lucille Duncan, a fifty-four-year-old domestic violence survivor with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and atrial fibrillation requested a mask and was denied one on April 3. On April 16, she wrote that the incarcerated population and guards had been provided with masks, but that they were optional. Governor Mike Parson had repeatedly said that mask-wearing was a matter of “personal responsibility” and choice, and had appeared, barefaced, at indoors events packed with elderly citizens. He reopened the state on May 4. The prisons, following suit, performed widespread testing beginning in late May and, when there were no new positive cases at Chillicothe, lifted restrictions. “Great job, everyone!” Anne L. Precythe, director of the Missouri Department of Corrections, wrote to staff on June 12. By June 25, an incarcerated woman wrote me to say that she had been notified that a Chillicothe employee tested positive for Covid-19. On July 13, Lucille reported that people were being moved around the facility without any apparent rationale. By early September, twenty-seven staff members and 252 incarcerated people had tested positive.

The movement of people within the prisons was an effective way for the virus to spread, but equally dangerous were new arrivals. Shortly after the WHO declared a pandemic, some states halted transfers from county jails and between prisons—but soon enough, many started back up. On April 3, less than three weeks after suspending non-critical inmate transfers, Florida prisons resumed intakes, even as daily cases in the state rose to more than a thousand.

Any individual transferred into an institution would be “placed on a 14-day quarantine limiting movement and interaction with the general inmate population except in emergencies,” the Florida Department of Corrections promised. But on April 16, Demetria Mason wrote me from Homestead Correctional Institute in Florida City, where she was serving ten years for a robbery, “We got a shipment of approximately 30 to 35 women…not one has been checked for symptoms and when the nurses come around they just ask if you are having ‘flu-like symptoms.’” Within the month, The Miami Herald called Homestead a “Covid-19 hot spot.” On May 26, Demetria wrote me, “death is sitting on my stomach.”

Demetria tested positive and was taken to a large, open dormitory filled with approximately sixty-five others. It smelled of mildew and bologna. Hives blossomed on her neck. One woman was vomiting blood, and “the staff just told her it’s part of the virus.” Demetria’s head and body ached, and she felt dirty: government-issued soap was in short supply, and her family members, short of funds, weren’t topping up her commissary account. When Demetria could sleep, she dreamed of her mother, who had died about a year earlier. Her mother had never acknowledged the sexual abuse Demetria suffered throughout childhood, but she had fed needy neighborhood kids and had never let Demetria or her sister “go without a Christmas, birthday, Thanksgiving, and telling us she loved us at night.” Demetria also dreamed of being reunited with her son. “Being a prison mom…is the hardest pain that I’ve had to endure. I will spend five more years of my life with my predator if I could just have all the time I’m away from my son back.”

By June 26, the Miami Herald reported that two women in the facility had died; within months, nearly 16,000 people held by the Florida Department of Corrections would test positive for Covid-19, the second-highest rate in the nation, and 107 would die. “I’m mad, then very sad,” Demetria wrote. “I feel like this will be my last place of stay.”

I reached spokespeople for the departments of corrections for the states of California, New York, Michigan, and Florida, as well as for New York City. They mostly declined to answer questions about specific conditions in their facilities but gave extensive information about the ways in which they were working to implement safeguards.

According to the Marshall Project’s Covid tracker, as of September 5, more than 115,000 incarcerated people throughout the country had tested positive for Covid-19, and at least 973 had died. But in many places with infections, there had been no widespread testing, or it had occurred weeks or months into the spread, suggesting that there had likely been earlier cases, and that fatalities may have been attributed to “natural causes.” Between March and August, of the twenty-six prisons I’d followed, twenty reported positive cases, ranging from two people at Taconic Correctional Facility in New York to 484 at Florida Women’s Reception Center.

In April several women from Nikki’s dorm at Bedford Hills were taken to the medical unit and did not immediately return. Within days, Nikki’s head began to pound, but she didn’t complain. She kept up her daily calls to her kids. Finally, in August, visitation reopened, with masks required, new screening procedures, and a limited number of people allowed in. The family was reunited. “They’ve grown so much,” Nikki wrote me. “I found new freckles on their noses, new beauty marks on their arms.”

Joe, in Minnesota, was fixated on preparing for his fifth parole hearing as Shakopee saw its first cases of the virus in July. The prison is located about thirty miles from the spot where George Floyd was killed by a police officer in May, setting off nationwide protests. Joe theorized that the murder exposed Minnesota’s “under the surface” bigotry, which extended to him. “I feel as if some of the guards would kill me if undetected…and feel no guilt,” he wrote. He gathered what he called a “small stash” of masks. His hands were cracked from constant scrubbing. He felt he could only count on himself for protection. Parole, he wrote, was like a “lotto, you can’t help but get your hopes up.” He wished to “salvage a little of a life.”

In California in August, cases were rising. Units around the one Tomiekia was assigned to were locked down, and a growing number of people tested positive. One woman wrote to me that temperatures topped 107 degrees inside. Another reported that the tap water was running warm. People who had been exposed to the virus were being rounded up and removed from their regular housing. Tomiekia had faith that God would bring her “out of the circumstances shining,” she told me. Still, late at night, she sat in a corner of her cell, “where no one else sees me, no one else knows,” she said. “I try to cry quietly.”

—September 10, 2020

This article was completed in partnership with Type Investigations. Reporting was contributed by Nina Zweig.

This Issue

October 8, 2020

Our Most Vulnerable Election

The Cults of Wagner

Simulating Democracy