We all could have ignored the Westboro Baptist Church, theoretically, but the opportunity to be party to a morality play seemed unusual and interesting, back then. It was a sunny day in 2014, just before the anniversary of the September 11 attacks, and protesters from the church had come all the way from Topeka, Kansas, to demonstrate on a street corner near my office in Manhattan. They had stopped there to protest my then employer, Gawker, as part of a swing through New York City designed to antagonize the media so that the media would pay attention to Westboro.

Everyone understood how the manipulation worked. Westboro was in decline then. Its founder, Fred Phelps, had died that spring, and the shock value of its mission—waving “GOD HATES FAGS” signs or taunting mourners at military funerals—had long since worn off. We might have kept working at our desks, but some sense that reporting or life required the witnessing of things led a few colleagues and me down the stairs and out to the street. The Westboro people brandished offensive signs and yelled, and counterprotesters tried to countershock them. A man in skivvies proudly made noise.

All of this was what Westboro wanted, although in truth it was a little sparse and desultory up close. I snapped a picture, juxtaposing a Westboro picket sign reading “THANK GOD 4 9/11” with a lamppost flier reading “Beautiful Nolita 1 BR Mott @ Prince $3200 for 10/1” and posted it to Gawker with no headline.

Many things would happen in the five and a half years after that. Gawker Media would be bankrupted, not for provoking the wrath of the Topekans’ angry God, but for having published rude things about the vindictive and very secular billionaire Peter Thiel. Self-referential publicity stunts and stupid, fleetingly apocalyptic online conflict—the Internet counterpart of Westboro’s pointless brawls—would become the substance of politics, shaping the application of real power in the real world. The punchline to decades of jokes about the worst imaginable president would become president. From inside the content-making machinery of 2014, perched on the ledge of the ring at the Twitter arena, it was possible to feel a new future coming, shapeless and terrible, yet it all seemed too dumb to be real.

“Everything is the internet now,” the New Yorker reporter Andrew Marantz told a colleague in 2016, in a conversation he recounts in Antisocial: Online Extremists, Techno-Utopians, and the Hijacking of the American Conversation. He was trying to explain to people within his normal, ostensibly enlightened social and professional circle—people who didn’t believe Donald Trump could possibly get elected—that the existence of “awful stuff” on the Internet, from the pickup-artist misogyny of lonely men to the scientific racism of organized xenophobes, could no longer be downplayed as a separate and irrelevant reality. “The awful stuff,” he went on, “might be winning.”

What does it mean for everything to be the Internet? “The natural state of the world is not connected,” the Facebook executive Andrew Bosworth wrote in a company memo in June of that same year. Bosworth was telling the people who worked under him why it was that their company would not waver from its program of worldwide expansion and infiltration, even if it meant people could be harmed.

“The ugly truth,” Bosworth wrote, “is that we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is de facto good.” This was before the world would read reports of Facebook’s part in pushing misinformation and fomenting artificial conflict in American elections, or in giving Myanmar’s military a platform to promote genocide, but already it was clear that Facebook had much to answer for, or to try to avoid answering for. The word “ugly” here only seemed pejorative; it was really chosen to position Facebook, under the conceptual scheme of the title of Sergio Leone’s most famous spaghetti western, outside the realm of “the good” and “the bad” alike.

Bosworth’s memo did not try to argue that the company’s unnatural focus on connection was demonstrably beneficial to humanity; it simply told the Facebook employees that it was beneficial to Facebook—that Facebook’s success as a business was the result of growth and market dominance: “Nothing makes Facebook as valuable as having your friends on it, and no product decisions have gotten as many friends on as the ones made in growth.” But good and bad still existed. Within a few months of Bosworth’s memo and Marantz’s warning, things got much uglier, but also clearly much worse.

Under Trump, the online mode of endless conflict for conflict’s sake became the daily mode of governance, as ever more wishful pundits kept waiting in vain for Trump to claim, even rhetorically, to be leading a united country. The White House filled up with an absurd collection of sideshow characters: the British-Hungarian blowhard Sebastian Gorka, with phony credentials and a real Fascist medal on his chest; the secretary of state Mike Pompeo, who dared a reporter to find Ukraine on a map as if it were impossible; the genuinely paranoid trade adviser Peter Navarro. Tucker Carlson, a frozen-food heir who warned his viewers that condescending elites were scheming with foreign invaders to take their country away, became the top-rated cable news host in the country. A shifting conspiracy theory driven by an online poster known only as Q—claiming that Trump was about to take down a global ruling-class crime network—led some of its believers to commit real-world acts of violence and others to win congressional primaries. Two mass shooters, one each in New Zealand and California, not only wrote manifestos citing the same xenophobic theories but also name-checked the controversial YouTube star Pewdiepie. The awful stuff—the unnatural stuff, by Marantz’s estimation—won. Was there a moral to be extracted from this? Or even an explanation?

Advertisement

It is hard to deny that, over the course of the past quarter-century, the Internet and then the devices and systems built on top of it have done something new and unsettling to the subjective experience of being human. In the face of fires and floods and Arctic heat waves, it has become untenable to deny that in the same span of time something has been damaged about the world in which people live. The social, political, and physical spheres have all entered a figuratively or literally hotter and more unstable state.

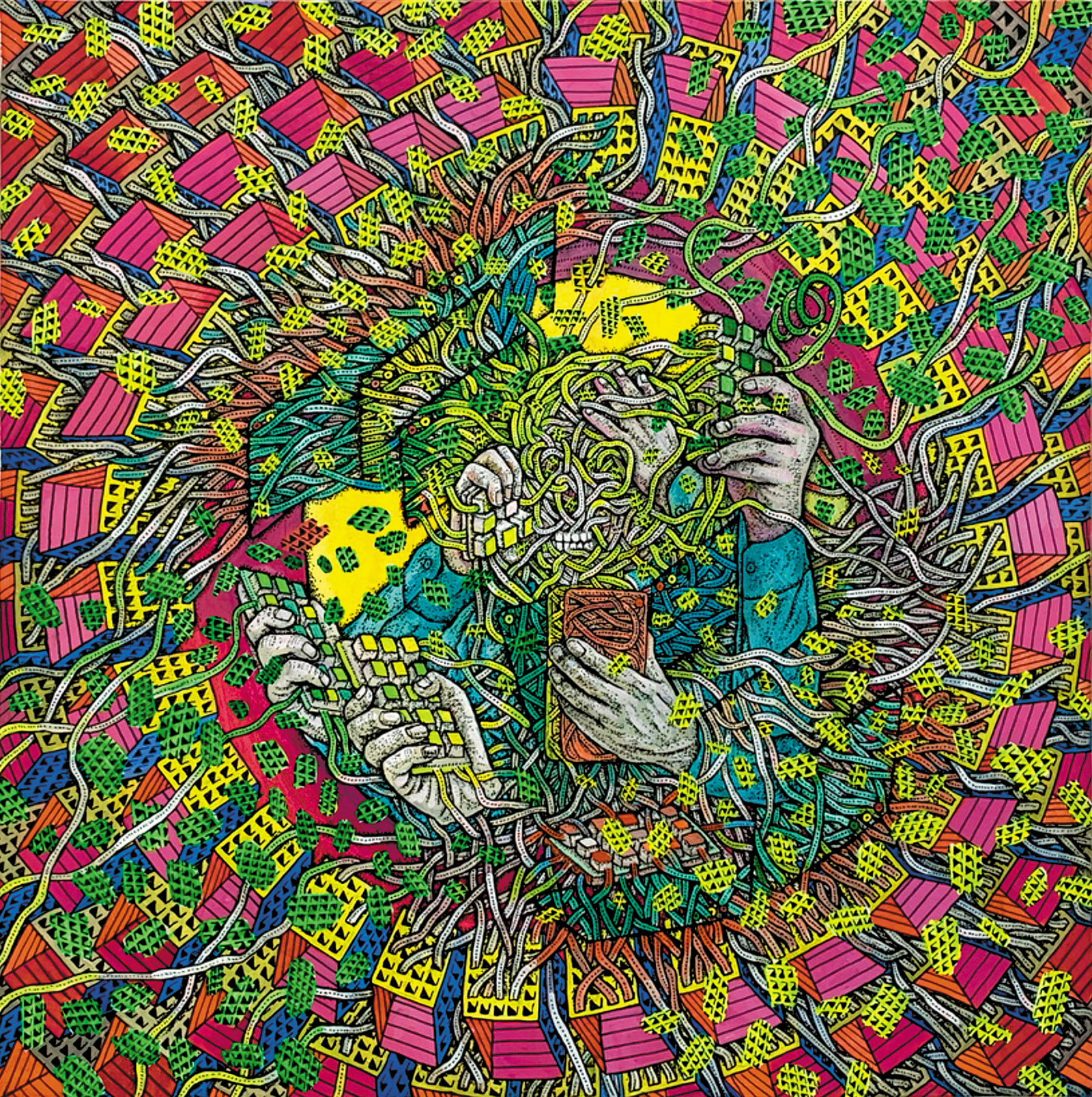

The online realm is no longer imaginable as a separate and frictionless alternative to the older plane of existence known, by disparaging retronym, as “meatspace”—that physical realm also called the “real world,” or, before that, the “world.” There are fibers of cyber running through the meat now, and bloody juices spattered on the inside of the screen. (The coronavirus has made the two even more indistinguishable, as people are forced to do the daily business of life remotely, while conspiratorial copy-pasted chain letters about mask rules send crowds out into the streets.)

Marantz was drawn to the site of the collision between virtual and real as it was happening, and tried to record what he’d seen in Antisocial. He profiles the people who were building the new systems, the moods and ideas that flourished at their offices, and the other people exploiting or being exploited by the new opportunities. He trails self-satisfied entrepreneurs to conferences and around business headquarters as they craft ever narrower-minded and further-reaching information distribution machinery; he tags along with the demi-celebrities of the online right wing as they navigate their rivalries and insecurities and their dreams of crushing the sphere of political liberalism. His subjects are cynical and obtuse at the same time, contemptuous toward the past and present but vacuous about the future they wish to bring on.

Meanwhile, one of the more horrible people online, Megan Phelps-Roper, the granddaughter of Fred Phelps and a third-generation Westboro Baptist provocateur, was trying to find a way out of her part in the system. In Unfollow: A Memoir of Loving and Leaving the Westboro Baptist Church, she describes a struggle not only to untangle herself from twisted bonds of family and faith but to establish a private self, behind the weaponized media persona she had grown up inflicting on the godless world. Phelps-Roper tells her life story as she grows from a dutiful child hate-picketer to a proud social media combatant for the church, battering the outside world with shock-memes and bigoted certitude even as she begins to reckon with private doubt and shame about Westboro’s mission. At last, frustrated by the church’s repressive governance and drawn out by generous online interlocutors, she and her sister Grace flee from Topeka to the Black Hills, where she begins constructing a new life as a champion of debate and discovery, launching a public speaking and writing career to present her own experience as proof of the redemptive power of open-minded discussion.

Both Marantz and Phelps-Roper, approaching the problem from opposite directions, have chosen titles that negate the contemporary techno-cultural imperatives: to be social, to follow, on the terms of the machines. What are those terms? Marantz writes about the rise of viral-content mills online, driven by the production of “high-arousal emotion” or “activating emotions”: curiosity, humor, “lust, and nostalgia, and envy, and outrage”—the feelings that get people to pay attention and react, in a measurable way, by using the available tools to click and share. Phelps-Roper describes the tactics of Westboro’s moral crusade in much the same way that Marantz’s amoral and meaning-agnostic content distributors describe their own work:

Advertisement

We gauged success primarily by the amount of media attention we received…. People often took our constant employment of shock tactics as cynical and purely attention-seeking behavior, but this was a fundamental misunderstanding of our purpose and the dynamics of the picket line. “Some say you’re just doing this for attention,” one television reporter accused Gramps during an interview I sat in on. My grandfather looked at her like she was uncommonly dense and said slowly, “Well, you’re doggone right. How can I preach to ’em if I don’t have their attention?”

The distinction between the religious fanatics and the click-chasers collapses still further as Phelps-Roper explains that, because Westboro’s fanatical conception of predestination held that God alone had the power to grant someone faith, the church refused to preach in a way that might persuade anyone to join it. “In light of this,” she writes, “our goal was not to convert, but rather to preach to as many people as possible, using all the means that God had put at our disposal.” Effectively, this is the same message that Marantz got from Emerson Spartz, the twenty-seven-year-old publisher of shareable and disposable mini-content across dozens of sites with names like Memestache and OMGFacts: “The ultimate barometer of quality is: if it gets shared, it’s quality.”

What “activating emotions” undermine is a sense of context and proportion. If enough people are paying attention to something—if you, personally, are paying attention to it, and it feels to you as if others are—it’s nearly impossible to conclude that it’s unimportant, or even to fit its importance onto a scale of relative importance. Likewise, if a thing gains and then loses public attention, it seems to have correspondingly lost importance. For a few giddy days in the spring of 2016, everyone was sharing a meme that arose from no known pop-cultural antecedent called Dat Boi, which depicted a 3D green frog on a unicycle, accompanied by the call-and-response text “here come dat boi!!!!!!” and “o shit waddup!” For a week or two in 2019, the news cycle was gravely concerned with the writer E. Jean Carroll’s detailed and credible account of how the man who is now president of the United States had raped her in the 1990s. What had felt all-consuming became nearly impossible to recall, except as a future trivia question.

With attention as the dominant value, all other values are in flux. Nearly anything can get in. Marantz opens his book in California, at “a free-speech happy hour—a meetup for local masculinists, neomonarchists, nihilist Twitter trolls, and other self-taught culture warriors.” Already the name of something Americans are taught to regard as a virtue—free speech—is a banner of vice, under which people unleash their cruelties or hatreds while treating their critics as oppressors. These are people who start fights online for the sake of starting fights, for whom the act of offending people is a self-evident victory. One of the attendees wears a T-shirt depicting Harambe, the zoo gorilla whose death had been an Internet sensation shortly after Dat Boi faded from memory. Marantz asks him to explain it: “‘It’s a funny thing people say, or post, or whatever,’ he said. ‘It’s, like—it’s just a thing on the internet.’” Marantz pauses to emphasize his own familiarity with the sort of numbness that goes with experiencing “much of life through the mediating effects of a screen,” and observes, “It wasn’t hard for me to imagine how anything—a dead gorilla, a gas chamber, a presidential election, a moral principle—could start to seem like just another thing on the internet.”

The delusion behind the rise of the Information Age was the same as the delusion that the end of cold war conflict had brought about what Francis Fukuyama called the “End of History”: that connection and exposure would necessarily breed enlightenment. Phelps-Roper supplies a helpful corrective, explaining how the biblical literalists of the Westboro Baptist Church navigated the mass media. From outside, it may have seemed as if the followers of Fred Phelps had to be ignorant, walled off from the faith-subverting power of secular and popular culture. Instead, Phelps-Roper writes of her upbringing:

We had wide latitude in our consumption of books, television, film, and music, and for much the same reason that we attended public schools: our parents weren’t particularly worried about negative influences slipping into our minds undetected.

Westboro was not afraid of popular culture; the church was popular culture.

Westboro members understood that they could despise the rest of the world without withdrawing from it. Participating in the discourse did not require them to share its values; they could attach themselves to it even as they detached themselves from empathy, solidarity, or, crucially, a mutually agreed upon substrate of truth. Phelps-Roper tells how her own loss of belief in the church was brought about, in part, by the elders’ decision to tweet out false claims that they had traveled to London to picket the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton, complete with Photoshopped images of Westboro members protesting outside Westminster Abbey, contrary to the scriptural prohibition on false witness. When caught in the fraud, Phelps-Roper writes, the church countered “that the fake picket was never meant to be taken literally…but this, too, was demonstrably false.”

Marantz observes the same dance of provocation and denial over and over among the revanchists and racists he talks to. Gavin McInnes, a cofounder of Vice magazine and later the founder of the protofascist street-fighting fraternity called the Proud Boys—who would eventually get himself banned from Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube for promoting hate speech and violence—constantly wiggles his toe over the boundary of outright bigotry, only to make a show of pulling it back. “Whenever a journalist implied that the Proud Boys were a white-pride organization,” Marantz writes,

McInnes claimed to be shocked and offended: “‘Western chauvinist’ [his preferred term] includes all races, religions, and sexual preferences.”… When he made a cogent argument, he was a political commentator; as soon as he crossed a line, he was only joking.

By now everyone is wearily familiar with this as the signature move of the president of the United States, to say a thing—the virus will disappear, the neo-Nazi demonstrators were fine people—while refusing to be held accountable for meaning it. As the Trump-promoting journalist (and accused fabulist) Salena Zito wrote for The Atlantic during the 2016 campaign, while noting yet another falsehood from the candidate, “the press takes him literally, but not seriously; his supporters take him seriously, but not literally.”

Four years of exposure to this routine, and more than 200,000 dead bodies, have made it clear that “literally” and “seriously” are not separable, nor are they cause for dismissing anything the president might say; the formulation itself was one more act of obfuscation. But good faith is a liability in a world built around seizing attention. What Marantz describes up close from the outside and Phelps-Roper narrates from within (and the president lives every moment of every day) is bullshit, in the invaluable and inescapable sense defined by Harry Frankfurt: the act of making claims without regard for whether they are true or false. It is a thing distinct from lying: the liars of the George W. Bush administration were focused on the truth and said the opposite, in order to conceal it; the Trump administration simply offers an incoherent flood of bullshit, in which the truth may as well not exist at all. The people of the Westboro Baptist Church believe strongly in something, while Marantz’s trolls and nihilists believe strongly in nothing, but their worldviews converge on a contempt for communicating honestly with ordinary people in the ordinary world.

“Anybody who was paying attention could see that the leaders of the Deplorable movement were not good-faith interlocutors,” Marantz writes. “They didn’t care to be.” What they were, he says more than once, is “metamedia insurgents”:

They spoke the language of politics, in part, because politics was the reality show that got the highest ratings; and yet their chief goal was not to help the United States become a more perfect union but to catalyze cultural conflict.

How do you bear witness to the creation of a matrix of falsity? The informational uselessness of what Marantz sees is the point; reason and observation are beset by intentional irrationality. Antisocial is a solid, printed book recording the fleeting furies of the Internet from 2014 to 2017; confronting it all again, after living through it once, felt a little like biting into bits of aluminum foil with a filling.

Here, holding forth on his “two primary laws of social media mechanics: ‘Conflict is attention’ and ‘Attention is influence,’” was the musclebound outrage-huckster Mike Cernovich, who’d harassed various colleagues of mine at Gawker when he seized a leadership role in the anti-anti-sexist outrage campaign known as Gamergate. He and his followers blitzed journalists with accusations of unethical and bullying behavior in coordinated waves of threats and complaints on Twitter, and in the process established the template for right-wing online warfare. Here was the vile clown McInnes—willing, at the urging of a guest on his YouTube show, to recite thirteen words of the white nationalist pledge known as the “Fourteen Words,” substituting only “a future for Western children” for “a future for white children”—joking with the white nationalist and future Toronto mayoral candidate Faith Goldy about relaunching the Crusades. Here was Lucian Wintrich, the briefly credentialed White House correspondent for The Gateway Pundit disinformation website, declaring, after the administration claimed the sparse inaugural crowd was the largest in history, “It’s just pretension and condescension, on the media’s part, to make a big deal of it.”

The paradox of the information and attention economy is that, while I knew most of the material in Marantz’s book on a rational level, it had gone by and deactivated me, too squalid and depressing to hold in my mind. It was easy to mistake it for being unreal, a collection of performances. “I know you from YouTube,” a secret confidant from the outside world tells Phelps-Roper via text message, as she grapples with her emerging sense that she needs to leave the church, “and your voice there is different from the one I hear when I read your words…. You aren’t real to people. You’re an idea.” This is the condition Marantz’s subjects aspire to. Late in the book, Cernovich tells him he’s trying to pivot away from being known as a Trump loyalist, deleting his old tweets and denying them. “Some people won’t believe you, but some people will,” he says. “It’s all in how you sell it. Meanwhile, I keep moving forward, and the old stuff keeps receding further into the past.”

Behind all the poses and manners, the world continues. Marantz is a keen and witty observer of the spectacle, attuned to the tension between his desire to expose figures who are “helping the lunatic fringe become the lunatic mainstream” and his knowledge that the act of exposing them grants those people’s own wish for mainstream attention. But observation only carries one so far. Early in Antisocial, Marantz hangs out with some Proud Boys and their allies as they prepare for the DeploraBall at Trump’s inauguration. One of the Proud Boys approaches a young woman on the scene, asking her if she’s the right-wing social-media figure Lauren Southern. She gives him a “long, withering stare” in return and walks off. She is, it turns out, a different member of the set of “rising social media stars with peroxide-blonde hair”: Laura Loomer, herself a far-right vocal Islamophobe. “An understandable mistake,” Marantz writes, and the moment remains pathetic. But it is much less amusing now that Loomer’s thirst for validation has won her the Republican nomination for Florida’s twenty-first congressional district—which earned her a tweet of enthusiastic congratulations from the president.

Later that evening, as Marantz follows the Proud Boys to the ball, a different interpretation of the whole story briefly presents itself:

Another protester, wearing a black ski mask and carrying an Antifa flag, passed by McInnes without incident, but McInnes shoved him anyway, then punched him in the face. “What the fuck?” the man shouted. Two police officers rushed to arrest the protester, while several other officers escorted McInnes into the Press Club.

In this moment, the Proud Boys’ posture as transgressive outsiders is belied by a grim, fundamental fact: the cops are on their side. Nearly four years later, it’s possible to forget that Gavin McInnes, who once commanded months of attention, exists. The part that feels scarily relevant, in the unraveling autumn of 2020, as the president tells the Proud Boys, in the first presidential debate, to “stand back and stand by,” is what Marantz went past on his way into the DeploraBall—the question of who is free to punch whom in the face, and who gets arrested for objecting to it.

Or, half-hopefully, there’s Phelps-Roper’s account of Fred Phelps, fading into dementia and soon to be stripped of his pastorship and church membership, stepping outside to face a group of activists who had bought the house opposite Westboro Baptist Church and painted it in LGBTQ rainbow colors. Phelps-Roper describes what her brother Zach told her had happened next:

“You’re good people,” Gramps called out to them from across the street, before he was hustled back inside by Westboro members. At the church meeting where he was excommunicated, the elders gave this incident as the clearest evidence of my grandfather’s heresy—casting his lot in with the Sodomites—and judged that he was lucid when it occurred.

The monstrous, consoling myth of the United States is that judgment is coming, but for someone else. The pious Westboro believers and the Internet crypto-Nazis and the sin-and-crime-soaked Trump administration share the same structure of faith: they are the elect, singled out for favor by God or fortune, and the rest of the world deserves nothing but suffering and contempt. In the space where righteousness used to be, there is a welter of competing self-righteousnesses. Where a nation might have been, there is a daily chart angling sharply upward, counting the pointless and preventable deaths of other people. We are, it turns out, all in this together.