More written about than read, more notorious than known, the British heiress Nancy Cunard has much to tell us and warn us against. She was born in 1896 into the Cunard shipping fortune and raised in the English countryside by a loving but distant father and a status-conscious, American-born mother—an unlikely background for a future agitator, leftist publisher, and civil rights advocate. In early 1919, she was severely struck by the Spanish flu. The following year, she moved to Paris, eventually befriending the surrealists and founding an important and innovative press. Her crowning achievement was the Negro anthology (1934), a costly, comprehensive 855-page volume celebrating Blackness and Harlem just as its Renaissance was ending. Negro charted the global force of Black culture, mapping itself onto ideas of race Cunard inherited and too often upheld, even as she sought radical change. Cunard’s attempts to ally with the Black cause and address what once was called the Negro Problem are instructive: not only did she reject high society, but she sought to reform society as a whole.

Seeing her as the archetypal New Woman, a number of writers, usually male, several of them former lovers and others who wished they were, devoted page after page to her charms during the interwar years: Evelyn Waugh, Tristan Tzara, Aldous Huxley (disguising her in three different novels), and Louis Aragon (in his obscene, banned novel, Le con d’Irène, which Cunard saved when he tried to burn it). T.S. Eliot satirized her in The Waste Land before Ezra Pound edited her out; Greta Garbo played a character modeled on her in the Oscar-nominated Woman of Affairs, adapted from a best-selling novel also based on her. Accounts of Cunard invariably describe her thinness, her startling blue eyes, and her “ivory skin”—adorned with African ivory bracelets from her collection, which numbered nearly a thousand. In his memoirs William Carlos Williams tried to capture her intoxicating presence, “her blue eyes completely untroubled, inviolable in her virginity of pure act. I never saw her drunk; I can imagine that she was never quite sober.”

After an early marriage to a wounded soldier, from whom she soon separated, Cunard shifted from the gossip pages to become a hostess very different from her socialite mother, at the center of her own bohemian scene in London. The group she later called, in one of her ambitious if uneven poetry volumes, a “Corrupt Coterie” overlapped with the Bloomsbury Group and other artistic outsiders. Cunard eventually moved to Paris and regularly visited Venice, where she romanced Pound and later returned with Aragon. There, in 1928, she met her most significant romantic partner, the African American jazz pianist Henry Crowder. Born in rural Georgia and raised in Atlanta, Crowder became, by his own description, “a central figure in the jazz musical field in Washington.” His band played Saturday nights at the club where Duke Ellington’s group gigged Mondays and Thursdays.

Eventually, Crowder began touring Europe with Eddie South’s Alabamians, who were in residence in the summer of 1928 at Venice’s Luna Hotel, where Cunard’s cousin Edward took her one night. “Here we met some people to me as being from another planet. They were colored musicians,” Nancy wrote in Grand Man (1954), her memoir of the writer Norman Douglas. After dancing all night, the cousins invited the band to join their party: “I had never met such enchanting people…their art, manners, the way they talked with us.” She was especially taken with Crowder, “the first Negro I had ever known.”

Pursued by Cunard, Crowder began an affair with her in Venice that continued in Paris. Their seven-year relationship helped inspire her years of civil rights activism in Europe, the United States, and elsewhere. Her romance wasn’t just with him, but with Blackness.

Paris was then the center of what was called le tumulte noir: from Brancusi to Picasso to Gertrude Stein, from Harry Crosby to Hart Crane, white modernists were obsessed with Blackness as a primal, primordial force—ironically, expatriate Americans often first encountered African American culture abroad. Such modernists regularly confused, or conflated, culture and color, sex and skin tone. In this they were not unique; white expatriates and Parisians alike fell for visions and fantasies of Blackness in hot spots like La Revue Nègre and other outbreaks of the Black tumult. Drinking, dancing, and not so much dining: Nancy regularly frequented what her spurned lover Richard Aldington slurred as “nigger cabarets,” including Le Bal Nègre, Zelli’s, Chez Florence, Le Grand Duc (where Langston Hughes washed dishes), and later Bricktop’s, where the eponymous singer introduced the Charleston to Cunard and the rest of Europe. Crowder was soon playing the Plantation, with its mural of slave times and a literal blackboard featuring chalk drawings of Negroes.

Advertisement

This interest in Blackness was driven in part by the manic-depressive cycle of the interwar era. The Roaring Twenties was a time of crazes, of dances like the black bottom, in what F. Scott Fitzgerald called “the greatest, gaudiest spree in history.” But Cunard later referred to the côté noir, or dark side, of the time, thinking of the surrealists she fell in with in Paris but speaking to the whole hectic modern pace, its wild vacillations, the way that “the suicide of young men, either from postwar despair, the despair of an artist or of a man who could not bear his inability to express himself fully, was in a sense honored.” Black culture represented the highs of the Jazz Age paired with a more severe, symbolic darkness often invoked for the lows. There was Black Tuesday, and Ernest Hemingway would call his own depression “black ass,” while the painter Gerald Murphy termed his blues “the Black Service.” Blackness to the white moderns meant both a “dark mood” and an admission of desire, providing an outlet for white expatriates in Europe as well as a form of seduction.

This fantasy invaded not just art and evenings out but dreams, some quite young: as Cunard remembered later in Grand Man, when she was six years old, her “thoughts began to be drawn towards Africa” and the Sahara, and she had

extraordinary dreams about black Africa—“The Dark Continent”—with Africans dancing and drumming around me, and I one of them, though still white, knowing, mysteriously enough, how to dance in their own manner. Everything was full of movement in these dreams; it was that which enabled me to escape in the end, going further, even further! And all of it was a mixture of apprehension that sometimes turned into joy, and even rapture.

Apprehension, joy, even rapture: such was the range of white reactions to Black culture that took root before and after the Great War. Cunard’s early dreams show how the idea of what I call the Black Colossus of culture held sway over those who didn’t actually know any Black people.

Cunard encountered her first lesson in racism almost as soon as she and Crowder left Venice, where “the fascist-minded” crowds hurled insults disguised as compliments—Ché bel Mero, “What a beautiful Moor”—and a disdainful Blackshirt on the train tried to tamper with their tickets. Paris was somewhat better, but in the French countryside, while driving the Bullet sports car she bought him, Crowder was fined and ordered to jail for getting hit by another car that was decidedly at fault.

Nancy was easily outraged—and could afford to be. She raced ahead into the self-righteous racial awareness of the newly converted. Crowder wrote later that he explained the US Constitution to her, and the contradictions and conditions under segregation; he was “amazed at Nancy’s absolute ignorance about such matters. But she was interested and eager to learn.” Still, she was better able to imagine American racism than to see it in England. On a clandestine trip to London, the couple found most of her usual hotels closed to them because of Crowder’s Blackness. She, in response, wanted to protest, turning every incident into a cause—and he just wanted to sleep, sometimes preferring to avoid racism rather than confront it. During the day she snuck away to see her mother.

There were other collisions to come. Nancy’s relationship with a Black man began to fascinate the public, stirring rumors among the “Black colony” of expats in Paris, as well as contempt from British high society. At a luncheon at her mother’s London house, the Countess of Oxford asked after Nancy: “What is it now—drink, drugs, or niggers?” Lady Emerald was horrified by her daughter’s match, which she could no longer deny. Her Ladyship, as Cunard always called her—her mother had changed her name from Maud—hired private detectives to harass her daughter and Crowder while they were staying above the favorite haunt of the “Corrupt Coterie,” even threatening the beloved barkeep. Her Ladyship tried to have Crowder arrested and wanted him deported back to the United States, in perhaps the first and only “Blacks Back to America” campaign.

Nancy’s reaction to all this was defiance and denial, as well as drinking too much and not eating enough. “I seem to be thinking of Africa all the time,” she wrote. She told friends like Bloomsbury’s David Garnett to come visit the couple in their Paris retreat, calling Crowder “a beautiful musician and a very wonderful person whom you would appreciate…. I say appreciate so often because it is their own colored world and exactly names the emotion.” She went on to publish a withering pamphlet, “Black Man and White Ladyship,” that excoriated her mother, spoofing her absurd questions: “Does anyone know any Negroes? I never heard of that. You mean in Paris then?… What sort of Negroes, what do they do? You mean to say they go into people’s houses?” Cunard sent the jeremiad to her entire social set, including the Prince of Wales. The gambit worked: she never saw her mother again.

Advertisement

Blackness had claimed her dreams since youth, after all, and justified the African artifacts she had collected throughout the 1920s. At her first dinner alone with Crowder, she had shown him her artifacts in her hotel room as part of the seduction. But did she collect Crowder too? Later on, he would seem to say so, calling his posthumously published memoir As Wonderful as All That?, the title distinctly a question.

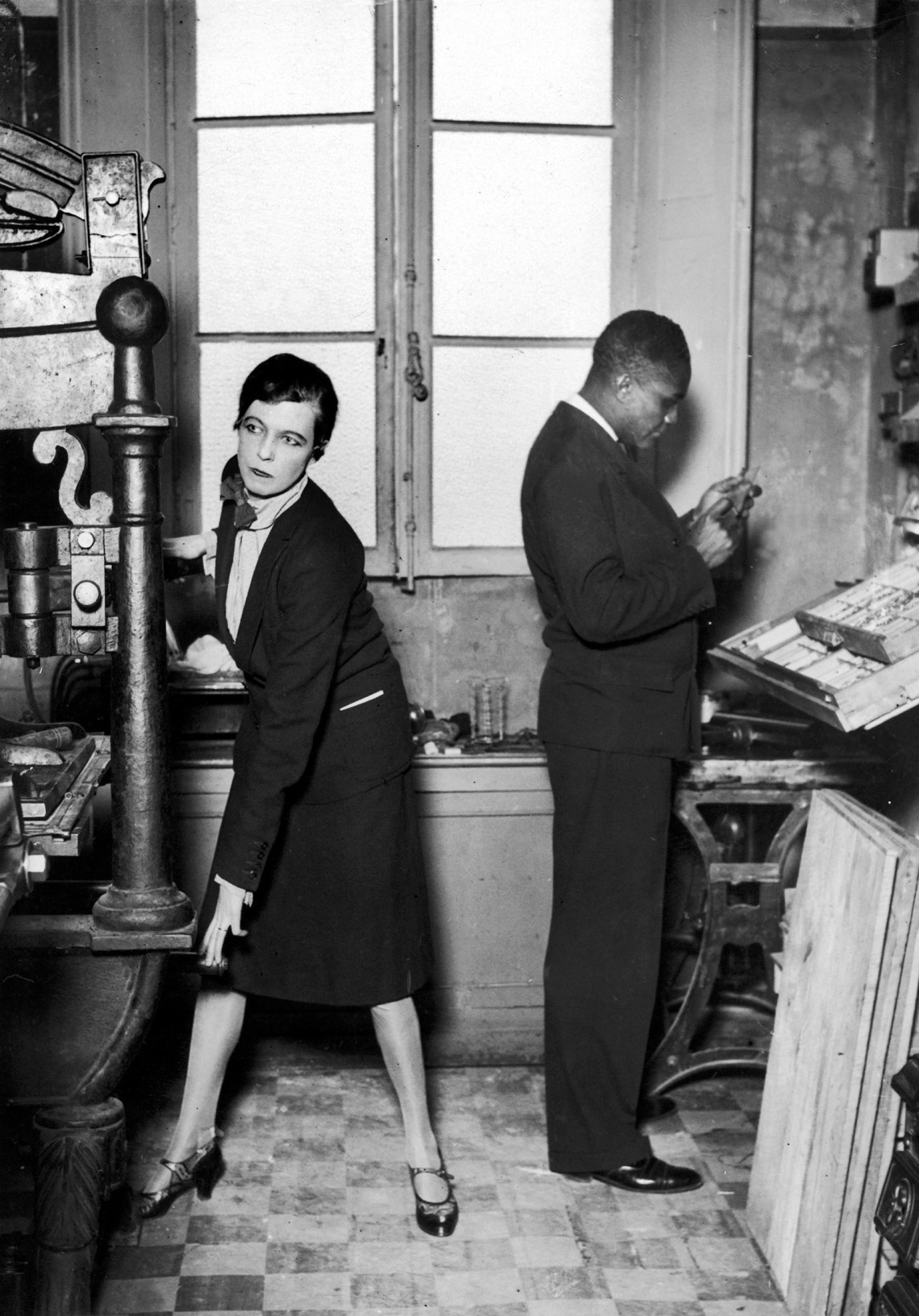

Early in 1928, knowing nothing of printing or publishing, Cunard bought the printing press of Three Mountains Press from the American journalist William Bird, who had first published Hemingway’s In Our Time. Bird helped set up the press in the stable of the farmhouse Cunard bought in La Chapelle-Réanville, Normandy, and provided a master printer to instruct her. Cunard was a quick study, pulling type and setting Aragon’s translation of Lewis Carroll’s Hunting of the Snark. She’d found her calling. The Hours Press became one of the last and most successful of the Parisian expatriate presses.

For Cunard the press’s name “was not only pleasing to me but suggestive of work.” She often set type all night and skipped meals to meet the deadlines she set. “Her austerity was voluptuous,” the writer Harold Acton remembered. Crowder joined her in Réanville, helping with the endeavor. She was passionate and precise in ways her own poetry only hinted at, and the messiness of her love life was belied by her elegant printing and design.

In 1930 Cunard moved back to Paris, bringing the press with her. There she announced a poetry contest, promising ten pounds and publication to the winner of the best poem of no more than a hundred lines on the subject of time. Cunard was disappointed with the submissions and complained enough that an acquaintance approached an unknown writer named Samuel Beckett about contributing. Within nine hours Beckett composed “Whoroscope,” a ninety-eight-line poem that he hand-delivered three hours past the midnight deadline; Cunard sent for him the next day, awarding him ten quid and his first publication.

Cunard was unafraid to have the Hours Press engage surrealism, mad experiments like Bob Brown’s Words, recent classics by George Moore and Arthur Symons, and poems by Robert Graves that sold out before publication. As its name suggested, the press’s existence was brief but timely, lasting only from 1928 to 1931.

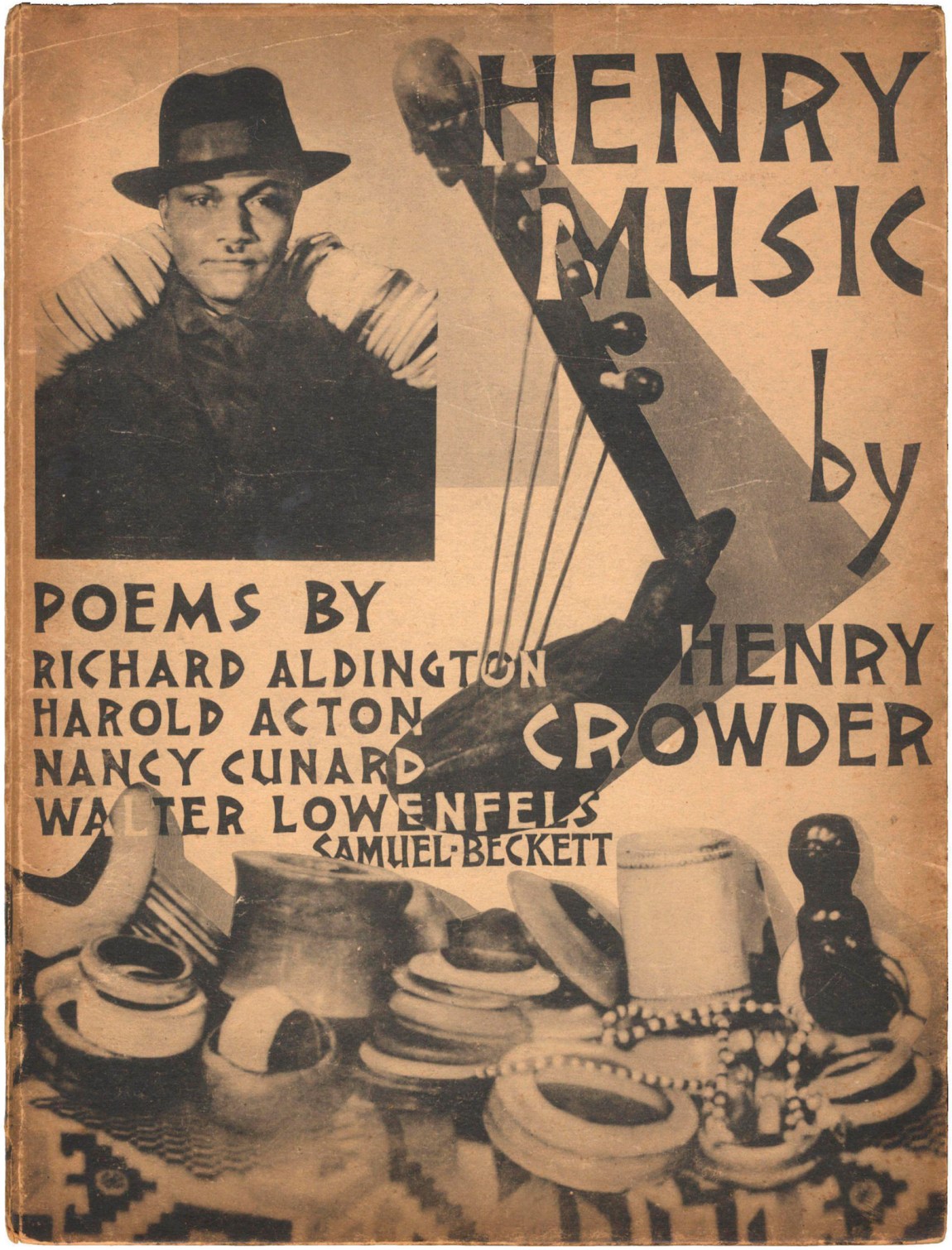

Cunard also published Crowder’s Henry-Music in 1930, with poems by Cunard, Acton, Richard Aldington, Walter Lowenfels, and Beckett (“From the Only Poet to a Shining Whore”) set to music. The cover image, by Man Ray, focuses on Henry’s natty, fedoraed face. At first it appears he’s wearing epaulets, until you realize those are Cunard’s African ivory bracelets, her forearms resting on Crowder’s shoulders, her hands and the rest of her hidden. Was she supporting him or pushing him into the spotlight? Henry-Music was one of the earliest collaborations between jazz and poetry, sidestepping orchestrations such as Cole Porter’s or Irving Berlin’s that sought to refine Blackness.

The volume also features Cunard’s “Equatorial Way,” a poem she said was “dictated by the romantic notion of the black man’s return to the Dark Continent.” In imagining a Black man abandoning his life in the New World for Africa, that place she had dreamed up while a lonely girl in her English manor, Cunard’s romance meant a rejection not just of America, which she perhaps desired for Crowder personally, but of the entire white world, which of course was her own:

With the days I slaved for hopes,

Now I’m cuttin all the ropes—

Gettin in my due of dough

From ofays that’ll miss me so—

Go-ing…Go-ing…

Where the arrow points due south.

I dont mean your redneck-farms,

I dont mean your Jim-Crow trains,

I mean Gaboon—

Although she avoids the worst of stereotypical dialect favored by other white writers—even now—her flurry of African American slang makes it obvious that Cunard has only just learned it, and her rhyme is a tin-eared affair. Being an “ofay,” she takes great care to call herself names by an imagined Black male speaker whom she never quite brings to life. It is hard to imagine what Crowder made of these words, including the N-word, put in his mouth. Even in encouraging his compositions, Cunard appeared to be orchestrating something else.

In 1931 nine Black teenagers—the youngest aged twelve—were falsely accused by authorities in Alabama of raping two white women while riding a freight train. Despite contradictory testimony and a lack of evidence, the court sentenced to death eight of the nine youths, known as the Scottsboro Boys. Such state-sanctioned railroading was an extension of the large mob that had massed at the jail demanding their lynching. Opposition to the verdicts united much of the left and further sparked Cunard’s political activism. She felt that groups like the NAACP were moving too cautiously, reluctant to rush into cases of race and rape, unlike the Communists whom she apparently embraced, even though she declared, “I am not a Communist—I am an anarchist!”

Later that year, Crowder accompanied Cunard on the first of her two journeys to the US, where, out of caution and her interest in all things Negro, they stayed in Harlem—first at the Hotel Dumas on 135th Street, then the Grampion, the nicest hotel in Harlem that allowed Black visitors. According to one of her many biographers, no white woman had stayed in either before. Harlem both enlivened and outraged Cunard; she lamented the “‘skin whitening’ and ‘anti-kink’ beauty parlors” she saw on her walks. Ironically, she criticized other whites whose “desire to get close to the other race has often nothing honest about it.”

While many hip whites would “go Harlem” for a night or weekend, Cunard ended up befriending some of the central figures of the Harlem Renaissance, meeting W.E.B. Du Bois and Walter White through Crowder, and trading enthusiastic and personal correspondence with Langston Hughes and Arturo Schomburg over the years. Schomburg wrote later that she had “made good” and was “merciless in her castigation of those white types who have not changed in their visions and perspective of life.” Still, Crowder felt frustrated by her failure to understand that even in Manhattan there were places off-limits to him, and that “everywhere we went we were stared at very belligerently.” For her part, she praised Harlem’s “gorgeous roughness,” with its “restlessness, desire, brooding” and its “noise, heat, cold, cries and colours.” And for now “Colour” was the name of the anthology that she began recruiting contributors for, with a 1931 circular announcing, “It will be entirely Documentary, exclusive of romance or fiction.”

By December, Cunard had returned to London to continue work on what became Negro, the final title recognizing a culture and not just a skin tone. The London press proved no better than the American papers in writing about her second time in Harlem in 1932, falsely accusing her of a tryst with Paul Robeson, who was staying at the same hotel. “Auntie Nancy’s Cabin—Down Among the Black Gentlemen of Harlem,” blared the Empire News. In response, Cunard held a press conference directing attention to the Scottsboro case and then savvily sued the British Allied newspapers, including the Empire News, winning the case and £1,500 for libel. The money covered the printing of Negro, an irony not lost on her: “I have never ceased admiring and marveling at that—as final as a tombstone.”

Negro was a life’s work. It took Cunard years—editing, writing, and traveling—to find essays and images, including photographic portraits of the 150 contributors she assembled from around the world. Undertaken with little in the way of a guiding thesis, in contrast to Alain Locke’s 1925 New Negro anthology (with its bold assertion of a new era), the book gathered the most prominent living Black writers and modernists. Hughes’s “I, Too” opened the volume, alongside a photo of a Black man labeled “An American Beast of Burden”; significant and groundbreaking recognition of Africa’s contributions to current life made up an entire section, including extensive photographs of African sculpture from museums and Cunard’s own impressive collection. In The New Negro, Countee Cullen’s poem “Heritage” had rhetorically asked, “What is Africa to me?”; Cunard’s question in her foreword to Negro was, unabashedly, “What is Africa?,” and of course she offered an answer:

A continent in the iron grip of its several imperialist oppressors. To some of these empires’ sons the Africans are not more than “niggers,” black man-power whom it is fit to dispossess of everything. At one time labelled en bloc “cannibals,” “savages,” who have never produced anything, etc., it is now the fashion to say that the white man is in Africa for the black man’s good. Reader, had you never heard of or seen any African sculpture I think the reproductions in this part would suggest to you that the Negro has a superb and individual sense of form and equal genius in his execution.

The anthology’s emphasis was global: Negro included sections on Africa, Europe, and the Americas, and suggested that what would soon be called Negritude was itself international. There were sections on poetry and drama, with strong contributions from Locke, Schomburg, newcomer Pauli Murray, and the younger generation of poets, including Cullen’s “Incident” and Hughes’s translations of the Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén, whom Cunard had sought out personally in Havana. Seven essays by Zora Neale Hurston, including her essential “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” were first published in Negro—appearing before her novels and nonfiction volumes, which would quickly go out of print for decades.

Beckett’s work translating French for the Negro anthology amounted to more than 63,000 words, marking his most significant appearance in print at that time. Beckett’s translations included René Crevel’s “The Negress in the Brothel,” which had been deemed obscene and so was printed separately and tipped in. Was it obscene or did it indict too well the perils of white desire? None of this stopped Cunard from making her own sweeping conclusions: “The American Negroes—this is a generalisation with hardly any exceptions—are utterly uninterested in, callous to what Africa is, and to what it was.” That she could write this after the Harlem Renaissance’s noted obsession with African heritage reveals her clueless fervor. “Much of her endearing gaiety was gone with the Twenties and though motives remained the same, provocations multiplied—mostly by privileged associations that only she was able to follow,” her friend Solita Solano remembered.

Though she’d only made it as far south as D.C., Cunard’s poem “Southern Sheriff” appeared in Negro in a section of white writers on Black themes—alongside her impressions of Harlem and Jamaica, where the shipping heiress had met Marcus Garvey, the exiled founder of the Black Star Line. She felt kind of colored, after all, and certainly entitled to hold forth on the issues of the day. She printed an essay indicting the NAACP as “a reactionary Negro organisation,” as well as the impressive essay “Scottsboro—and Other Scottsboros,” which sees the case as not an exception but the rule. For good measure, Cunard included some of the prodigious hate mail she’d received from her time in Harlem, sent to her at her hotel. “Notice how many of the whites are unreal in America; they are dim,” she wrote in the entry “Harlem Reviewed.” “But the Negro is very real; he is there.”

Rather than being merely “documentary,” Negro offered testimony, especially regarding the music she was immersed in through Crowder. The white composer George Antheil’s essay “The Negro on the Spiral, or, A Method of Negro Music” declared Black music central to European thought and healing after World War I: “This was the war which exhausted the world and left it without a grain of its former ‘spirituality.’… Nothing could survive underneath this dense heat and smoke except Negro music.” Confirming Black influence on European art, Antheil cited Modigliani, de Chirico, the Dadaists, who “collected every bit of Negro sculpture,” and the surrealists, who “in 1924 exhibited the best of it with their own painters.”

Antheil viewed the transformation Black music provided as geographic, even seismic—“We found ourselves in the Parisian veldt”—and routed through the Americas via “the jug of Africa.” Despite his dated essentialism, Antheil evoked the sun and a searing Blackness as a remedy to “the waste land” of Europe and even the flu virus:

We welcomed this sunburnt and primitive feeling, we laid our blankets in the sun and it killed all of our civilised microbes. The Negro came naturally into this blazing light, and has remained there. The black man (the exact opposite color of ourselves!) has appeared to us suddenly like a true phenomenon. Like a photograph of ourselves he is the sole negative from which a positive may be drawn!

As with Cunard, is it enough for Antheil to be well-meaning? Does this language that conjures tanning and burning transcend the “negative”? In a section of Negro simply titled “Negro Stars,” Robert Goffin praised Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong while making a similar connection: “What Breton and Aragon did for poetry in 1920, Chirico and Ernst for painting, had been instinctively accomplished…by humble Negro musicians.” The effect was a description of Black genius that originated beyond Europe’s shores but utterly changed European and American culture.

Cunard’s grand collection helped signal a shift away from white authors and artists borrowing Black culture—whether from the African continent, the Southland, or the city—while viewing it as more or less raw material for them to mine, if they recognized it at all. Far too many white modernists saw such inspiration as just another type of Black labor, invisible, underpaid, unacknowledged. Picasso, Brancusi, Man Ray, Giacometti, Stein, and Braque had all acted like they’d struck the mother lode in being inspired by the kinds of African icons that Cunard featured in Negro. But when she wasn’t seeing Black life as simply struggle, or wearing it on her wrists like weapons, she managed to recognize Blackness as an aesthetic, an outlook, a way of thinking that Black folks well knew. No wonder Black people had long kept their culture hidden—invisibility provided both an ironic commentary on being unseen and resistance to being disregarded. Rather than trumpet Black culture as Cunard did, artists such as Brancusi sculpted The White Negress instead, which Cunard took to mean her.

Upon Negro’s release, Locke wrote Cunard, “I congratulate you—almost enviously, on the finest anthology in every sense of the word, ever compiled on the Negro.” Hughes declared it “marvellous.” While Crowder later wrote that “the book has many very glaring faults, some of which I consider pitiful,” he praised the anthology privately—after all, it was dedicated to him. “The gratitude of the Negro race is yours,” he wrote her. “Nancy you have done well. You have made the name Cunard stand for more than ships. Your deep sympathy for the Negro breathes through the pages.” This marked a benedictory end to their turbulent, transformative relationship.

Negro was originally bound in brown buckram, and that edition’s heft often causes its spine to split—one encounters a smoother black binding as remedy—but size seems one of its selling points. The book’s bounty was a form of praise. Negro made an argument in its beauty too: as Hurston writes of the Black aesthetic in “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” “There can never be enough of beauty, let alone too much.” More collaborative than a benefactor, more sympathetic than a patron, Cunard was also more than a simple activist—at times acting, at others acting up, she regularly used her fame as a form of action.

“Nancy was a great hater and a great lover,” remembered one friend in Brave Poet, Indomitable Rebel, a collective posthumous tribute. “She hated food passionately.” Her appetites lay elsewhere. She lived openly and at times, it seemed, carelessly, if not callously: when she first went to Harlem with Crowder in 1931, she was actually living with her printer’s devil, Raymond Michelet, who was sixteen years her junior. Michelet wrote the longest contribution to Negro, an essay called “The White Man Is Killing Africa.” The theme was Nancy’s, whose foreword concluded: “The truth is that Africa is tragedy.”

Nancy’s tragedy is that, despite her tremendous labor of love, in type and image, she ultimately couldn’t imagine an Africa beyond her youthful fantasies. Despite her emphasis on Black genius, she was still foregrounding herself as the white savior. Was Crowder right that Negro’s “production is an extraordinary example of persistence in the face of tremendous odds, the greatest of which was ignorance,” meaning Cunard’s? Viewing Blackness as monolithic, her ideas about it were as large and unwieldy as the book she assembled. She urged Crowder to “be more African”; Cunard deigned to say what kind of Black was best, a problem of overfamiliarity, while refusing to admit her own views sprang from a need to outrage her own highborn origins. But when Crowder died in 1955, Cunard wrote a friend, “Henry made me. I thank him.”

Cunard continued her political activity after Negro, but she was damaged, like her ideals. Increasingly paranoid in her last years, which included stays in sanitoriums, in 1965 she died in an orphans’ hospital, as alone as she’d felt in childhood. Even there, “refusing food, writing, writing, writing dementedly on her last long poem,” as a friend put it later, Nancy Cunard sought to name injustice—requesting paper for an epic, she told attendants, against all wars.

This Issue

December 2, 2021

Grand Illusion

Herring-Gray Skies