Amy Mee-Ran Dorin Kobus was adopted from South Korea in 1974, at the age of six. In an essay for the anthology Voices from Another Place: A Collection of Works from a Generation Born in Korea and Adopted to Other Countries (1999), she recalls “kicking and screaming” as she was taken to her new home in North Branch, Minnesota, by white adoptive parents. “I worked diligently to become the model American,” she writes. “I dressed in American clothes, took speech tutoring to rid myself of my Korean accent, and, most important, I acted American.” Still, she felt unsettled by her past:

Most adopted children have questions about their biological parents such as, “Why was I given up for adoption?” “Didn’t my family want me?” and “Who were my real mother and father?” Those were my questions too.

Dorin Kobus’s adoptive mother, encouraging her to explore her heritage, took her to a Korean cultural program in Minneapolis. After high school, her adoptive parents sponsored her trip to Korea with twenty other adoptees, a “motherland tour.” She visited an orphanage like the one in which she spent her infancy, but did not manage to find her birth parents. On the way back, she was asked to escort a thirteen-month-old baby boy to his adoptive family in the United States. “During the long flight I cared for the baby as if it were my own, knowing I would have to give him up,” she writes. “I thought of my biological mother and her possible feelings when giving me up. I am certain she cried many tears.”

Over the past seven decades, some 200,000 South Korean children have been adopted abroad, mostly to the US but also to Canada, Europe, and Australia. For many years, South Korea was the top exporting nation for international adoptions; more recently, that distinction has belonged to China, which has sent more than 126,000 children abroad since 2000. Korean adoptions began in the 1950s, with the well-intentioned rescue of “war orphans” during and after the Korean War. Many of these children indeed had no living family; others were “social orphans” who’d been separated from their parents in the fighting or were considered unassimilable owing to racial and social stigmas. In Voices from Another Place, Kat Turner, the adoptive daughter of a pastor in Iowa, describes herself at a telling distance: she is, she writes, the mixed-race “product of an American soldier in Korea as a result of the war.”1

It didn’t take long for transnational adoption to go from emergency response to permanent bureaucracy. For the South Korean government, out-adoption became a substitute for costly antipoverty programs: in 1960 the country’s per capita GDP was just $158, compared with $475 in Japan.2 Churches and social services agencies in the West, meanwhile, aggressively marketed Korean children to prospective adoptive parents. One couple described their adoptive daughters as targets of their evangelicalism: “Our girls are our mission field, this brings us great pride. We never see a nationality difference.” As Arissa H. Oh writes in To Save the Children of Korea (2015), South Korea designed a template for interracial family-making that planners in Vietnam, Central and Latin America, India, Russia, Romania, and China later used to send children to the West. International adoption became a long-term form of child welfare and, despite many people’s best intentions, “a public market in which children were commodified, sourced, and shipped overseas like packages.”

South Korean adoptions peaked in 1985, more than three decades after the Korean War and well into the nation’s economic rise. By then, thousands of transnational adoptees were reaching adulthood. In the US, they were emboldened by growing racial awareness and increased scrutiny of the child welfare system. In 1972 the National Association of Black Social Workers issued a statement against transracial adoption, asserting that “only a black family can transmit the emotional and sensitive subtleties of perception and reaction essential for a black child’s survival in a racist society.” Several years later, Native activists won passage of the Indian Child Welfare Act, which recognizes the “essential tribal relations of Indian people” and requires that Native children be placed with kin whenever possible.

Beginning in the 1990s, Korean adoptees met through organizing networks and at international conferences as well as on the early Internet. They shared their experiences of estrangement and uncannily similar accounts of why they had been abandoned (desperate teenage parents) or why their vital records were incomplete (fires and floods). They returned to Korea on motherland tours, visiting orphanages and trying to locate their birth parents.

In time, they began to tell their own stories. The first anglophone adoptee memoirs appeared in Voices from Another Place and another collection, Seeds from a Silent Tree: An Anthology by Korean Adoptees (1997). Then came The Language of Blood (2003), a lyrical recollection by Jane Jeong Trenka, who later became a leading adoptee activist. Trenka describes a sort of double birth:

Advertisement

My name is Jeong Kyong-Ah….

Halfway around the world, I am someone else.

I am Jane Marie Brauer, created September 26, 1972, when I was carried off an airplane onto American soil.

As a young child in the Midwest, Trenka is taught to feel grateful but cannot shake a sense of dread:

“We chose you,” my mommy always says. To me that means from a store…. A thought comes to me now, a frightening thought that makes sense as I sit alone: I could also be returned to the store. I could be exchanged for a better girl.

Korean adoptees, especially in North America and Europe, have since produced numerous works of memoir, poetry, film, and visual art. The American poet and English professor Jennifer Kwon Dobbs has written autofictionally of found family: “An hour into reunion, Appa and I match/pace 1-2-3 drink! and I want to sing/the only Korean song I know.” Another US adoptee, Deann Borshay Liem, made two documentaries about being adopted under the identity of another girl from her orphanage. Jane Jin Kaisen, an adoptee raised in Denmark, represented Korea at the 2019 Venice Biennale, with an installation based on the folktale of Princess Bari, an abandoned daughter who becomes a powerful shaman. And Malene Choi, also Danish, took a refreshingly experimental approach in her feature film The Return (2018). In one scene, an adoptee named Thomas posts xeroxed signs all over the tiny Korean island where he was cared for by a foster mother before being sent to Denmark: “가족을 찾습니다” (Looking for my family).

While the first wave of memoirs had an unvarnished, diaristic quality, there is now a greater diversity in content and style. Today’s authors are Korean adoptees from all over the world; their stories still involve searching for their birth families, but much more besides. Three recent books show how the genre has evolved alongside the community. Lisa Wool-Rim Sjöblom’s graphic novel Palimpsest: Documents from a Korean Adoption, Jenny Heijun Wills’s Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related., and Nicole Chung’s All You Can Ever Know present complex narratives informed by the histories of earlier adoptees. All three women find and meet their families of origin—a rare feat that’s understandably overrepresented in adoptee memoirs (what better story line is there?). Along the way, they discover unexpected bonds whose tenderness surpasses even that of the birth mother.

The adoptee memoir is a genre of return, so we should start at the beginning, with the American couple who created the prototype of transnational adoption. In 1953 Harry Holt, an evangelical lumberman from Oregon, and his wife, Bertha, adopted eight Korean children orphaned by the war. They went on to establish Holt International, which grew into one of the largest adoption agencies in the world. The Holts were motivated by charity, but they also recognized a business opportunity. The ravaged South Korean state did, too: war orphans were a photogenic conduit for foreign aid, and Western parents were willing to pay to adopt from overseas.

The Korean War had left millions of people displaced. Families were scattered and split, including by the division of Korea into North and South. Among those lost or abandoned were large numbers of “Amerasian” and Black children born to Korean women and the American GIs who’d occupied the Korean Peninsula since the end of World War II. The South Korean government was eager to send these mixed-race children abroad, and the US obliged. In 1955 President Eisenhower signed into law An Act for the Relief of Certain Korean War Orphans, selectively loosening restrictions on Asian immigration. As Thomas Park Clement recalls in his memoir The Unforgotten War (1998), early adoptees like him depended on individualized acts of Congress—sometimes named for the child in question—to be let in. (The vagaries of immigration law have left thousands of transnational adoptees in the US and Canada without immigration status; some have been deported to their countries of birth. In the US, the Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2021 would provide relief for undocumented adoptees, but it is stalled in Congress.)

Eleana Kim, an anthropologist at the University of California at Irvine and the author of Adopted Territory: Transnational Korean Adoptees and the Politics of Belonging (2010), found that, between 1951 and 1964, the number of abandoned children at orphanages in South Korea grew from 715 to 11,319. The number of children adopted overseas increased every year between 1953 and 1985, when nearly nine thousand children left South Korea, primarily for the US. Why weren’t more children adopted internally, within Korea? A common sociological explanation is that East Asians, with their strict familial maps, were culturally indisposed toward adoption. There’s truth to this, but other factors mattered just as much: poverty and stigma toward the offspring of single mothers, a lack of social services, prejudice against mixed-race families, and welfare workers who encouraged poor and unmarried parents to give up their children.

Advertisement

Adoptees sent to the West often grew up racially isolated but found themselves, and one another, in the multicultural climate of higher education. Then, beginning in the 1990s, something unlikely happened: many of them settled permanently in South Korea. Adoptees like Jane Jeong Trenka worked across barriers of language and culture to study the fundamental reasons for their adoptions. Were it not for the mistreatment of unwed mothers and discrimination against mixed-race Koreans, they reasoned, perhaps they would not have been sent away.3 Adoptees also raised questions of material distribution: What if the resources put toward adoption had gone instead to the birth family? The point is as relevant to Korean adoptees as to indigenous children sent to Canadian residential schools and the African American and Latino kids disproportionately placed in foster care.

In subsequent years, returning Korean adoptees fought successfully for welfare reforms and their right to due process in South Korea. In 1999 a coalition led by the group Global Overseas Adoptees’ Link won a campaign to expand the Korean F-4 visa: adoptees now had the right of other ethnic Koreans to reside long-term in the country. In 2011 activist adoptees further secured the right to dual citizenship and helped enact dramatic changes to the adoption laws: the government now requires robust notice and consent procedures to protect birth parents’ rights. (Partly as a result, only 259 children were adopted out of South Korea in 2019.)

Last year, Kara Bos, who was adopted by a Michigan couple in 1984 after being left in a parking lot at the age of two, successfully sued in Korean court to be legally recognized as the daughter of her birth father, even though he refused to meet her. (Some adoptees worry that her lawsuit will discourage other birth parents from coming forward.) As Kristin Pak, an adoptee organizer in Korea, told me, the right to know one’s family, one’s history, and one’s birth nation is a basic human right. Pak believes that transnational adoption is intrinsically flawed. “It’s not about having a good adoption or bad adoption,” she said. “This whole system is demand-driven. It’s very unequal.”

While the adoptee memoirs anthologized in the 1990s were works of confession and communion, the books emerging now are full of confidence and rage. They are wider in scope, critical of the choices made by the US and Korean governments, and sharpened by scholarship on global adoption.

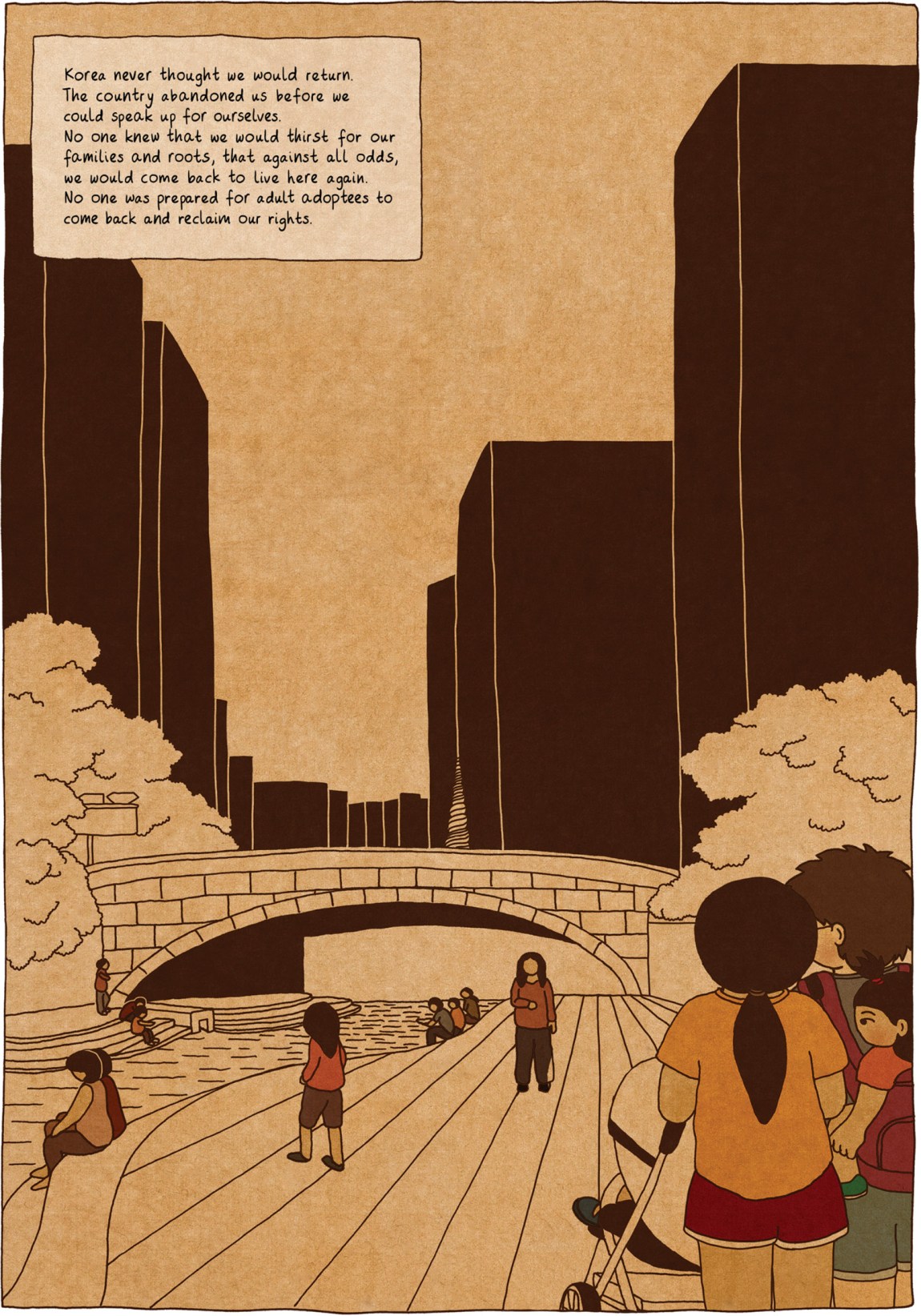

Lisa Sjöblom’s graphic novel, Palimpsest, is the tale of a Swedish adoptee who was removed from South Korea at the age of two, in 1979. The book unfolds in sepia-toned rectangular panels whose lengthy text sometimes competes with the soft, spherical characters and detailed backgrounds. Many frames consist entirely of letters and recreated documents: adoption case files and e-mailed pleas for information in a mix of Korean and English. As a transnational, transracial adoptee, Sjöblom questions her origins at a young age. Her adoptive father tells her, simply, “I’m sure your mom loved you, but she gave you away to give you a better life.” Yet at school, she is bullied for being Asian. Her classmates tie her to a post. We watch her face flush, her body shrink in on itself. As an adolescent, “in an attempt to save myself, I asked my parents to help me find my Korean roots,” she writes. Her parents agree, but a callous Swedish social worker discourages them partway through the search: “We can only hope that Lisa’s mother today has a family, a husband, and children. A revelation of Lisa’s existence would most likely break up that family and cause even more people pain.”

According to Jennifer Kwon Dobbs, the Korean-adoptee experience in Scandinavia is marked by “a kind of colorblindness that’s much more intense there than in the US.” For Sjöblom, it isn’t until she has married and settled down in cosmopolitan Stockholm that she feels ready to reconsider her origins. When she becomes pregnant—the book’s cover illustration is of a fetus—and is unable to tell the obstetrician about her family’s health history, she decides to look again for her birth parents. Pregnancy is a common turning point in the memoirs of female adoptees.

Things are different this time. Online, Sjöblom finds “critical adoption forums” full of peer advice. A Korean-speaking friend helps her e-mail the “countless middlemen involved in an adoption.” After months of correspondence, Sjöblom receives “the photo I’ve been waiting for all my life”—a picture of her birth mother, whom the authorities in Busan, South Korea, have finally located. The following summer, Sjöblom goes to Korea with her husband and two children. They meet her birth mother at a restaurant and hug and weep and do their best to relate, despite an intractable language barrier. In two imagined panels, Sjöblom rests her head in her mother’s lap and speaks with ease. But in real life, they bumble through with an interpreter, and her birth mother turns away, begging Sjöblom not to ask about the past. Sjöblom learns that she has siblings and that her father is still alive, yet she meets no one besides her mother.

At a popular beach in Busan, Sjöblom encounters a stranger who comes to represent a substitute mother. The woman gazes admiringly at Sjöblom and her family and invites them to tea. Upon hearing Sjöblom’s story, she says, “If it turns out she’s not your real mom, I can be instead.” The scene distills an increasingly prevalent motif in adoptee memoirs and activist life: a focus beyond the birth mother. These days, according to Mike Mullen of Also-Known-As, an adoptee advocacy group in New York, the “search” extends not only to other blood relatives but also to the foster mothers who provided pre-adoptive care in South Korea, often for up to a year or two.

Jenny Heijun Wills’s memoir, Older Sister. Not Necessarily Related., depicts an extreme version of this dynamic. Whereas Sjöblom struggles to connect just with her birth mother, Wills, an English professor at the University of Winnipeg and the adopted daughter of a white Canadian family, contends with an overflow of attachments. She goes to Korea hoping to find her birth mother and perhaps her father. But it’s a younger half-sister she hadn’t known about who “would become the most important person in all of this,” she writes. Wills begins her book with a warning:

This story, these stories are not all mine. Some of them, in fact, belong to no one at all, but are the fantasies that seem to flower so naturally from the mouths of those of us who’ve grown lives out of half facts, wishful thinking, and outright lies.

The book entangles fiction and truth—in vignettes, vaguely chronological meditations, and letters to Unni, the Korean word for a girl’s older sister. Its form simulates the fragmentary, one-step-forward, one-step-back journey of many adoptees.

Wills’s trip to Korea becomes unwieldy. She meets not only her birth mother and younger half-sister, Bora, whom she’d spoken with by phone, but also her father and his side of the family, including an older half-sister. Wills learns the reason for her adoption—she was the product of an affair—and watches herself become a “tripwire,” blowing “shrapnel through at least three generations”:

To my older sister, unni…I embodied years of deception and our father’s betrayal. I represented her mother’s sadness. For Halmoni [grandmother], I’d caused years of blackmail, a secret that kept a poor family of grape farmers ground down into the earth…. Even for Bora, the one to whom I was closest, I had caused pain. Bora’s father’s rage used to burst open without apparent cause. My sister didn’t understand the source of her father’s hatred for Ummah [mom].

Things get weirder still. Wills’s Korean parents, having lost touch over the intervening decades, reunite to meet their daughter in Seoul. They fall in love with her—then with each other. To the shock of their extended families, the couple moves in together and travels to Canada for Wills’s wedding, as does Bora. It’s the kind of improbable, transpacific reunion that an adoptee might dream about, but no fantasy can last.

Like Wills’s book, Nicole Chung’s All You Can Ever Know is a story of sisters. Chung, a Korean adoptee and a contributing writer at The Atlantic, dedicates her memoir to a newfound sister—one she meets in the course of looking for her birth mother. But Chung’s search has the rare distinction of unfolding outside Korea: she was adopted not overseas but across the Washington–Oregon border. Chung’s adoptive parents are white Christians in the rural east of Oregon. Her life with them is placid, but she wants to be normal, meaning not Asian. She knows only that she was born premature in Seattle and in need of a decent home. Her adoptive mother tells her repeatedly, “Your birth parents had just moved here from Korea. They thought they wouldn’t be able to give you the life you deserved.”

In high school, Chung tries to contact the attorney who handled her adoption. It’s only then that her mother confides that the lawyer had called them years ago: “Your birth mother asked her to get in touch with us.” But Chung’s parents refused contact. “I understood that they didn’t want me to want to search. I was enough for them, and they wanted to be enough for me,” Chung writes of their crisscrossed desires. Much like Sjöblom, Chung swallows her curiosity until she’s pregnant with her first child. She suddenly thinks of “those mysterious months my birth mother had spent carrying me” and wonders, “What had pregnancy been like for her? Why had she gone into labor so early? What if the same thing happened to me?”

Chung hires a “search angel,” a sort of adoption private eye, who fills in her past, bit by bit. “Two sisters, a half sister and a full one, had been living at home at the time I was born,” Chung is told. Her birth parents divorced six years later and now live in different states—neither more than a few hours’ drive from where Chung grew up. Chung drafts and redrafts a simple letter, to be forwarded to her birth mother. “I am your biological daughter,” she writes. “I want you to know that I am well, and happy, and have lived a good life.”

She receives e-mails from both of her sisters in reply. “Nicole, I was very shocked to find out I had another sister,” Cindy, her full sister, writes. “I don’t know how much you want to know. Our parents told us that you had died.” Chung learns that her birth parents had been unhappily married and short of money, running a small store while trying to raise two girls. Their mother could be cruel, their father unavailable. When Chung was born two and a half months premature, they gave her up at the hospital.

After the divorce Cindy went to live with their mother. (The older half-sister was already away at school.) But after six months, “she grabbed her belongings—everything she had packed fit into a couple of plastic grocery sacks—and nervously bid her mother goodbye.” Their relationship never recovered, and Cindy moved in with her father, who remarried a year later.

“There are many different kinds of luck,” Chung realizes, “many different ways to be blessed or cursed.” Her family search does not lead her to a Korean motherland or original maternal embrace. But it does bring her Cindy, who also suffered rejection and pictured what life might have been like in a different family. “I don’t know how you would have been treated if you’d stayed with us, Nikki, but I know your sisters would have loved you and tried to protect you,” Cindy tells Chung. The reunited sisters, though living on different coasts, visit each other regularly with their husbands and children—a kind of rebirth.

A few years ago Korean American friends of mine, a married couple in New Jersey, adopted a boy from Korea through Holt International. The process was long and complicated, with repeated visits and court hearings to safeguard the rights of the birth family—the reforms that returning adoptees had pushed for. I overlapped with them in Seoul on one of their pre-adoptive trips to meet their new son. “Back in the day, you could start your adoption process and a kid would be delivered to you at JFK, and they’d be five months old,” the wife told me. “Now it’s impossible to get a kid home earlier than two.” She and her husband understood the critiques of transnational adoption. But they felt that they were well situated, as Korean Americans, to adopt a Korean child. When they brought their son to the US from a nurturing foster home in Busan, they reminded him where he’d come from. They created an album of his pre-adoptive life and tried to read him children’s books about adoption. None of this interested him; he wanted only to be an American kid and use his American name. “I do wonder how he’ll feel later,” the wife said.

A lesson of adoptee memoirs, including those by Chung, Wills, and Sjöblom, is that adoption, search, and reunion are not discrete events but unruly processes that continue throughout an adoptee’s life. At each step, new bonds are haltingly formed. Existing bonds can grow stronger or threaten to break apart. For Chung, the presence of her Korean parents and Korean American sisters forced a revision of the “family lore given to us as children.” It was no longer gospel truth, she writes, “that my birth family had loved me from the start; that my parents, in turn, were meant to adopt me; and that the story unfolded as it should have.”

-

1

Kori Graves’s book, A War Born Family: African American Adoption in the Wake of the Korean War (NYU Press, 2020), documents how Black Korean children were advertised for adoption to Black couples in the United States, especially those with military ties. ↩

-

2

Japan’s own economic recovery after World War II was due to a war boom: it served as an industrial and military ally to the United States during the Korean War. ↩

-

3

Although the birthrate in South Korea is the lowest it has ever been—so low that the government provides all kinds of financial incentives for procreation—unwed and nonheterosexual parents are still stigmatized, and immigration is tightly restricted. ↩