In Welcome to Lagos, a TV miniseries broadcast a dozen years ago, the BBC claimed to turn a compassionate lens on the sprawling Nigerian city of at least 10 million, which it portrayed as an uncaring and brutal place populated by resourceful poor people, rogues, and vagabonds. The program followed impoverished inhabitants eking out a living on the beach, at the lagoon, and at a rubbish dump.

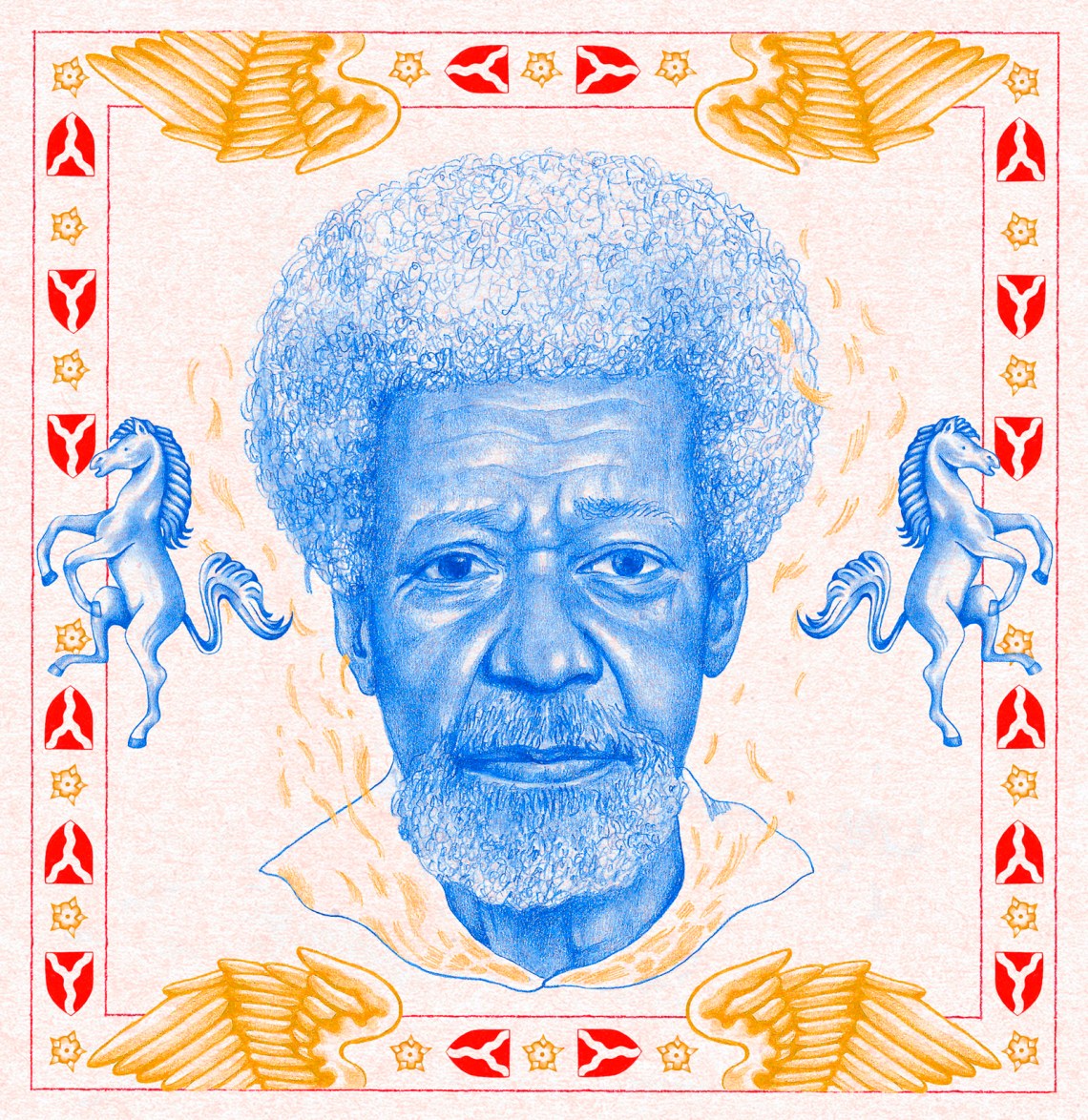

When Nigeria’s Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka watched the episodes, he struggled to contain his ire at what he considered a reflection of the worst aspects of Britain’s attitude toward its former colony. The depiction was “jaundiced and extremely patronizing,” he lamented, as if it were saying, “Oh, look at these people who can make a living from the pit of degradation.” Lagos, as a microcosm for Nigeria, acted as a soiled canvas, Soyinka implied, on which others, largely ignorant of the society’s nuances, had too often and without sanction imprinted their prejudices. The BBC was guilty of a reductive portrayal of a richly vibrant city.

Soyinka’s complaint has long been echoed by his contemporaries and by younger generations, who have questioned the myriad hackneyed ways the continent and its cities are depicted by outsiders. In his fiercely satirical essay “How to Write About Africa,” the Kenyan writer Binyavanga Wainaina advised:

Never have a picture of a well-adjusted African on the cover of your book…. An AK-47, prominent ribs, naked breasts: use these…. Taboo subjects: ordinary domestic scenes, love between Africans (unless a death is involved).

Soyinka would concur, though in writing about Nigeria he has at times sounded like a relative who is happy to voice criticism of family members himself but takes umbrage when a nonmember articulates similar sentiments.

When he was in his early thirties this prolific poet, playwright, and essayist had two intensely solitary years to ponder his homeland: in 1967 he was imprisoned without trial for twenty-six months by Nigeria’s military regime for presuming to act as a peacemaker during the war over Biafran secession. Soyinka chronicled his detention in the memoir The Man Died, recalling how he was cruelly kept in a compound where the condemned were usually housed ahead of their execution.

He had thought to call the book A Slow Lynching, but the final title arrived unbidden one day when he was inquiring about a Nigerian journalist who’d been badly beaten by police and hospitalized. A cable informed him simply, “The Man Died.” Later Soyinka reflected on the terrible news:

I was struck first by the phrasing. It sounded weird, yet familiar…. The ending to a moral tale…a catechumenical pronouncement, the eyes of a surgeon above the mask, or the surprise of a torturer that misjudged his strength. I heard the sound in many different voices from the past and from the future. It seemed to me that this really is the social condition of tyranny—the man died…the matter is dead.

The man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny.

In numerous plays, essays, and speeches over the decades, Soyinka called out the tyranny of Nigerian regimes and their moral corrosion, which infected the country’s institutions and schooled its population. He called for fundamental change, even as he was tolerated by each new government only because he was Africa’s first winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. The critical assessment outlined in those hundreds of thousands of unsparing words has not, though, found its way into one of his novels for almost fifty years, until now.

The title Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth is ironic. Finland ranks as the world’s happiest country; Nigeria is nowhere near the top ten. And in this novelized rendition of Africa’s richest and most populous nation, a satire in broad brushstrokes focused mostly on the elite and establishment figures, all the characters accept the title’s description of the country as a necessary or useful fiction.

The book sets out to be an all-encompassing state-of-the-nation novel, looking at Nigeria’s broken society through four fictional figures: the oleaginous prime minister, Sir Godfrey Danfere (Sir Goddie); a media mogul, Chief Modu Udensi Oromotaya, proprietor of the salacious newspaper The National Inquest; Papa Davina, an evangelical preacher who presides over a megachurch; and an altruistic public servant, the philosophical surgeon Dr. Kighare Menka. Only Menka is clear-eyed, enraged, and passionate enough to articulate the urgent need for the population to wake from its torpor (his voice and outlook are perhaps closest to Soyinka’s); the other three are cynical, self-serving narcissists.

Ekumenika, Papa Davina’s healing ministry, is located in a festering neighborhood with “scattered ledges of iron sheets, clay tiles, and corrugated tin rooftops” alongside isolated pockets of “ultra-modern high-rise buildings.” To get to his sacred retreat, seekers and penitents must wade through “pebbles and screed, garbage that sometimes featured both human and animal faeces.” Early on Papa Davina puts a positive spin on the negative assumptions about Nigeria:

Advertisement

There are many, including our fellow citizens who describe this nation as one vast dung heap…. [But] if the world produces dung, the dung must pile up somewhere…. It means we are performing a service to humanity.

Davina has worked hard to create his ministry, but his evangelism has garnered him a fortune. Preacher-entrepreneurs have long attracted the attention of novelists and journalists. In 2011 Forbes published a list of the five richest pastors in Nigeria, whose combined net worth was estimated at $199–$235 million. Soyinka complicates the stereotype with Davina’s idiosyncratic backstory.

Like several of the other characters, as a young adult Davina (then known as Dennis Tibidje) spent time studying in Europe, but he took more interest in female companions than his required reading list and dropped out to try his luck traveling without a visa to the US, a folly that earned him months in a detention center. His incarceration, during which he read widely about self-made men, brought on a kind of epiphany: God called and, on being deported, Dennis Tibidje, fired by the captivating story of the messianic African American preacher Father Divine (circa 1876–1965), transformed himself into a pastor.

Father Divine provided the template for Papa Davina, who began sporting a gold-topped walking stick and dressing “mannequin sharp in a three-piece suit…with an embroidered waistcoat that glittered with gemstones.” His signature hybrid look, “his face wreathed in camouflage,” included a “neutralizing turban and sunglasses,” and his voice exuded rapture.

Early chapters of the novel devoted to Davina can be confusing, partly because of Soyinka’s layering of detail without giving any initial sense of its relative importance, but primarily because of the character’s various name changes. From Dennis Tibidje, the overseas student goes through several versions of himself before he settles on the vision of a “creative spiritual trafficker.” He starts by traversing the country in a camper and holding impromptu revivalist meetings, and finally becomes a national celebrity, “the Gardener of Souls,” Apostle Tibidje.

The obsessive zeal for taking a new name, thereby reinventing oneself and improving on one’s identity, is found throughout the population. Even the dissatisfied prime minister Sir Goddie upgrades his title to “the People’s Steward.” “‘Branding’ is a word entirely free of irony,” the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has said, “and [Nigerians] use it to refer even to themselves. ‘I want to become a big brand,’ young people brazenly say.”

In Chronicles, the country’s leaders have also learned its value. The phrase “The Happiest People in the World” is a consummate exercise in rebranding. The Ministry of Happiness distracts the population with fiestas and innumerable nationwide awards, including the Yeomen of the Year Award (YoY) and the People’s Award for the Common Touch (PACT). The competitive awards seem tantalizingly winnable, and though resignation to one’s fate is a national pastime, there’s also a popular belief in divine intervention to improve the chances of winning and escaping one’s destiny. The power of prayerful change for individuals is echoed in the state’s National Day of Prayers “against drought, floods, diseases, corruption, locust invasion,…kidnappers, paedophiles, traffic carnage, ritual killers, etc., etc.” Luckily the “Gardener of Souls” does not just confine himself to his congregation’s spiritual health; he’s a modern Moses with an electronic staff, we’re told, tuned to detecting oil reserves, for instance, beneath farmland and ancestral fishing ponds.

Papa Davina assuredly navigates a world of increasing religious militancy predating Boko Haram. The Maitatsine, for example, warred against orthodox Muslims and, incensed by “all who rode in any mechanical conveyance,” strangled cyclists with their own bicycle chains. He builds a new church and religious movement: Chrislam, a unifying hybrid of Christianity and Islam. More than a building, though, it’s a religious city that rises on an island near the town of Lokoja where two rivers met. His new ministry also becomes a political hangout, and Davina is appointed the prime minister’s official spiritual adviser.

In Soyinka’s critique of the rule and confluence of politicians and religious figures, obsequiousness is the governing characteristic; the nation is on its knees. Sir Goddie’s office is “a heaving Uriah heap of oozing unctuousness.” His assistant, Shekere Garuba, whose job appears to be little more than “ensuring that the prime ministerial kola nut bowl was steadily replenished,” is the personification of this attitude. Soyinka devotes a page to describing the simple act of Garuba preparing to knock on the PM’s door as he adjusts his demeanor for a favorable response from the boss. The message appears to be: in a society of scoundrels, you’d best get up off your knees and work your way into a position where others will genuflect to you. “Victims act inhumanly,” Soyinka has argued, “to become the very things that had degraded them as human beings in the first place.”

Advertisement

Soyinka readily admits that he’s more of a dramatist than a novelist. He has struggled to capture the unwholesomeness of the tumult and collective lack of self-awareness of Nigerian society and has proposed that the novel offers the best format for composing a contemporary tapestry of the country. Chronicles is energetic and sets off at quite a pace. The ambition is admirable but the book bulges with a superabundance of characters barely sketched beyond caricature; as a consequence it soon becomes unbalanced and unwieldy. Even a significant character such as Papa Davina is absent for long passages.

Nevertheless, a lacerating satirical sharpness propels the book, and if at times it appears overwritten, that is consistent partly with the feeling of hysteria and a country careering out of control: bombs explode with sickening regularity and the collapse of buildings “had become the companion sounds of existence”; bizarre killings happen on the streets in broad daylight, including at one point a decapitation, succinctly described: the assailant “whipped off the brown paper wrapping and out flashed a machete…. [He uttered] a violent curse in some unfamiliar language…a swish, and with that single stroke the man lopped off the head” of another man standing in line at a bus stop.

Elsewhere, hapless victims pile up on Lagos’s treacherous roads from accidents, and sometimes a driver caught in traffic risks becoming a statistic of “accidental discharge” from a policeman’s or soldier’s gun. The randomness of state violence following an unwitting transgression is rendered in one of the most chilling passages of the book:

All it took was for even a low-ranking sergeant to take offence at another motorist, who perhaps refused to give way to his car, a mere “bloody civilian,” never mind that the latter had the right of way. An on-the-spot educational measure was mandated. Guns bristling, his accompanying detail, trained to obey even the command of a mere twitch of the lip, leapt from their escort vehicle, dragged out the hapless driver, unbuckled their studded belts, whipped him senseless, threw him in the car boot or on the floor of the escort van, and took him to their barracks for further instruction. However, the wretch sometimes created a problem by suffocating en route.

The idealistic Dr. Menka is one of four friends who style themselves the “Gong of Four”—an allusion to the Chinese Communist Gang of Four, but these Nigerians are socially engaged and altruistic. The Gong of Four have remained close since their days abroad at university, when they pledged on returning home to do something, as repayment for the investment in them, for the betterment of the country. With the passage of time, pragmatism has tempered their ambition. Now, seasoned and in their fifties, none is so naive as to doubt the wisdom of the assertion once made by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: “To live in Lagos is to live on distrust.” That distrust is most evident in electoral corruption, which elicits a collective shrug of the shoulders in Soyinka’s novel: “International observers had their say, then went home to document their findings. What difference did it make? mocked the victorious, lamented the losers.”

All the members of the Gong of Four hope to swim free from this sea of corruption but cannot entirely; to do so would be to surrender to its tyranny. Prince Badetona (aka the Scoffer), a fastidious government accountant, becomes embroiled in a financial scandal (engineered by the authorities) and is imprisoned. Farodion is an elusive promoter in the entertainment industry who has strayed from the gang and is barely mentioned.

Duyole Pitan-Payne remains the most upbeat of them, buoyed by a permanent amusement that helps him rise above Nigeria’s squalor, physical and psychological. He’s an engineer and entrepreneur who, to the bewilderment of civil servants such as Shekere Garuba, is promoted to a post at the UN as a consultant to its Energy Commission on the basis of his actual experience and expertise. “He was sufficiently immodest to know that he had earned it on merit,” the narrator notes, and that in itself presents a problem. Pitan-Payne is not a party man, cannot be influenced, and is not biddable. Why then, the PM’s adviser wonders, would such a man be rewarded when there are other more deserving candidates who are eager to pay for the honor of representing their country at the UN?

One of the frustrations of the book is that Garuba, along with a handful of other characters whom Soyinka spends only a brief time developing, primarily serves the satire. They include Pitan-Payne’s siblings: the feckless rascal Teahole, whose illogic gets the better of any logical thinker; and Selina, a disparaging snob whose brittle voice resembles “a piece of grit scratching on the windows.” Both exemplify the elite Nigerians who loathe their poor compatriots and unsophisticated country. They exist in a vacuum, unencumbered by any sense of morality; they are delightfully despicable, and drive the conscientious Dr. Menka to distraction.

Soyinka places his surgeon at the moral center of the novel; he is the touchstone of empathy. It’s a fascinating choice. If there’s one character who can possibly act as a “repairer of the breach,” then it is the doctor. For much of the time Menka appears sanguine, accepting, as all surgeons must, the brutality of their profession even when they are obliged to violate the medical code that has existed for millennia: First, do no harm. In yet another backstory—the book is replete with reports of seminal moments from characters’ pasts—we learn that Menka carried out the instruction from a sharia court to amputate the arm of a convicted thief. Slowly the good doctor’s resilience starts to unravel. In the past, witnessing each abuse “merely sealed up channels of emotional response except one—rage.” Soyinka appears to be saying that in a society like Nigeria, the temptation is to surrender to despair, but as long as we still have the capacity for rage, then hope remains.

In the midst of the chaos and jeopardy Menka takes refuge in his gentlemen’s club, the Hilltop Manor at Jos, in the Plateau State. The elegant imperial hangout—with glazed wood paneling; bleached, outdated British journals; and a welcoming banner inscribed “Manners Maketh Man”—offers respite from the ill-mannered chaos beyond its doors. But Menka causes consternation when, his nerves beginning to fray, he lashes out in an extraordinary “round of self-savaging” at his own complacency and especially that of his fellow members. Dr. Bedside Manners (as they call him) suffers mentally not from the escalating horror of Boko Haram’s increasing atrocities but rather from the “civilian demonism” pervading the land. Perversely he finds relief in attempting to rationalize beliefs that justified the horror, and in trying “to configure visions of that future whose gateway some could only glimpse through mangled humanity.”

Even Menka, though, cannot really fathom the overtures from sinister businessmen—who are aware of the amputation he performed on the thief—to involve him in their venture, trading body parts, which the narrator describes as “Human Resources.” This dark commerce—one that will have a deleterious impact, especially on the heroic Gong of Four—is the turning point of the novel and the inevitable conclusion, the narrator suggests, of decades of dehumanizing the population:

Indifference turns to active toleration, butchery turns vicarious, a form of grim but gleeful participatory theatre. How was it possible not to anticipate the logical end, the terminus of remorseless logic of a progressive dulling of sensibilities that underlay the furtive patronage of a once unthinkable commerce.

Notwithstanding some perfunctory plotting about the alignment of church and government in the business of Human Resources, it is a riveting conceit; the trade in human body parts—centered in Badagry, a small town close to Lagos from which enslaved Africans were dispatched during the Atlantic slave trade—is a metaphor for the state devouring its own people.

When Pitan-Payne comes close to discovering the scheme, he is sent a mail bomb and blown up, an event as calamitous as “a sinkhole opened up in the midst of a crowded intersection.” Here Soyinka reprises the trope of The Man Died about the dangers and necessity of resisting tyranny. Pitan-Payne is a fictional stand-in for Dele Giwa, the Nigerian investigative journalist who was assassinated in 1986, the same year that Soyinka won the Nobel Prize. (Giwa is one of the three people to whom Soyinka dedicates his novel.)

The assassination of Pitan-Payne—the best the country has to offer—is a shock and a travesty that diminishes everyone; it should not be possible or countenanced. Could it help rejuvenate others, a challenge to the notion that “once breath is gone, the rest is sentiment”? The narrator notes that the intense and torturous preparations for the repatriation of the body of Menka’s friend from Salzburg (where he had been airlifted for emergency treatment) serve “as a palliative for the neglected areas of [Menka’s] existence.” But the state’s cynicism is unending. Pitan-Payne is declared a martyr, and Sir Goddie and his advisers plan for a regular festival to be inaugurated in his name.

Satire is always difficult to get right. If a writer has to spell out his intentions, then satire fails. It was the satirical edge of many of Soyinka’s early plays and essays that made his writing so forceful. The satire here is more of a blunt instrument. This long-awaited novel, a fusion of dark comedy and grotesque exaggeration, invites sympathetic reverence for the author, now in his eighties, and the kind of unrealistic hope for another masterpiece found in admirers of genius artists whose best work is behind them.

Even so, Soyinka has created a portrait of a nation that has lost its way, is inured to corruption and violence, and can seemingly no longer be shocked beyond a pervasive ennui. It’s a bleak picture that nonetheless has cracks of optimism about the possibility of finding allies to retrieve humanity. Soyinka is neither defeatist nor downcast. His book is sometimes vexing and at other times exhilarating. Its form—loose yet always charged with explosive potential—perfectly mirrors the elusive idiosyncrasies of a society that others, less able and emotionally intelligent than he, whether writers or broadcasters, have struggled to convey.

Soyinka saves some of his most droll and visceral writing for the denouement of the final chapter, when a power outage sends swaths of Lagos into darkness:

The huge gloved hand silenced him and blotted out the neighbourhood…. A thin streak of residual light lingered over a distant rim of rooftops, treetops, and hilltops, the last being sometimes camouflaged mounds of multi-textured garbage jutting out between the glove’s widespread fingers and unseen ooze…. [A] progressive orchestration of generator spurts, gearing up for extended runs…drowned out the agonised and resentful shrieks.

Finally, the tone of Soyinka’s writing, as he looks squarely at the terrible truths of his homeland, is one of weary impotence as the ghoulish details unfold and the story grinds to its end. Though the rendering of violence is not pornographic, the novel reveals a dispirited population resigned to amoral leaders who are quietly constructing a state governed by a kind of cannibalism. The passage of fifty years between Soyinka’s second novel and his third suggests that Chronicles from the Land of the Happiest People on Earth may be his last. It is very dark; depictions of postcolonial Nigeria don’t get much darker.