“A specter is haunting America,” intones the right-wing propagandist Dinesh D’Souza. “The specter of socialism.” As he speaks, in the opening sequence of his 2020 documentary Trump Card, we are shown a dramatic montage, including a CGI fly-through of Manhattan. The Statue of Liberty has been replaced by Lenin. There’s a hammer and sickle on the front of the New York Stock Exchange. “The death toll of socialism is unimaginable,” D’Souza explains. “Over 100 million casualties.” In an odd dramatized sequence, a uniformed interrogator threatens a man shackled to a table, his head hooked up to some kind of steampunk electrical contraption. The message is clear: socialism is totalitarian. It is—or inevitably leads to—Soviet-style state communism. It operates by coercion and mind control.

In his 2019 State of the Union speech, D’Souza’s hero, President Trump, reassured his base that “America will never be a socialist country.” Americans have long been encouraged to see socialism, however they understand it, as fundamentally alien, a collectivist threat to a national polity founded on the sanctity of the individual as economic actor and bearer of rights. As early as 1896 the famous editorial writer William Allen White attacked the Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan by warning that the election would “sustain Americanism or…plant socialism,” a racialized choice between “American, Democratic, Saxon” and “European, Socialistic, Latin.”

A recent Pew Research poll found that 55 percent of those surveyed had a negative perception of socialism, while 42 percent felt positively. The most commonly cited reason for a negative view was that it “undermines work ethic [and] increases reliance on government.” But other recent surveys found that a majority of Americans support policies identified with socialism, such as a fifteen-dollar minimum wage and higher taxation of the rich. America’s most prominent socialist organization is currently the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), founded in the early 1980s through a merger of two existing groups, one that had split with the conservative “old left” of the labor movement over its support of the Vietnam War, the other with a background in “New Left” student radicalism.

The DSA aims to be what its official history calls an “ecumenical, multitendency socialist organization,” a project that had never attracted more than a few thousand dues-paying members until the 2016 presidential campaign of Bernie Sanders, which introduced this brand of popular-front socialism to a wider audience. Since the start of the Covid pandemic, membership has exploded, standing at around 95,000 at the time of the group’s 2021 National Convention. In 2018 two DSA members, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Rashida Tlaib, were elected to the House of Representatives. In 2020 they were joined by Jamaal Bowman and Cori Bush.

Contemporary American socialism exists on a continuum between social democrats, who want to achieve a fairer settlement within market capitalism, and democratic socialists, who want to bring various activities, from housing to health care, under some form of state, community, cooperative, or employee control. Democratic socialists have transformative ambitions, but unlike Communists, their goal is not the abolition of private property. They accept, to varying degrees, the utility of markets, but disagree with classical free marketeers who see the economy as a self-regulating system that works most efficiently when insulated from the “distortion” of nonmarket forces; they insist instead on what the Austro-Hungarian economist Karl Polanyi called “embeddedness,” the emergence of the economy from—and dependence on—social, political, and cultural relations.

This kind of thinking has never been popular with American elites, who have historically used the press, public information campaigns, think tanks, and corporate lobbyists to turn public opinion against it. But while the demonization of socialism has a long history in the US, so does American socialism itself. The movement whose tangled history Gary Dorrien tells in American Democratic Socialism has deep roots in the very “American” values it is accused of undermining.

American socialism predates Marx. Early experiments in communal living and working included intentional communities such as New Harmony, Indiana, founded by followers of the Welsh social reformer Robert Owen in 1825, and Utopia, Ohio, founded by disciples of Charles Fourier in 1844. The word “socialist” is usually held to have entered the English language in 1827, when it appeared in the pages of the Owenite Co-operative Magazine. By the 1830s “socialism” had been brought into conceptual opposition with “individualism,” creating the basic contours of our contemporary political landscape.

Owenites started the first American labor party, the Working Men’s Party, which put a carpenter into the New York State Assembly in 1829, and they became involved in abolitionism and campaigns for public control of land. Owen’s famous demand for a shorter workday became a rallying cry for the American labor movement, under the slogan “eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, eight hours for what you will.” The bumper sticker reminder that “if you enjoy your weekend, thank a union” speaks out of a political tradition that is two hundred years old.

Advertisement

After the failure of the European revolutions of 1848, many German “forty-eighters” fled to the US, exposing Americans to currents of European socialist thought. They became Republican legislators, land reformers, and Union soldiers in the Civil War. As Dorrien writes, figures like Friedrich Karl Franz Hecker, the cofounder of the Illinois Republican Party, and Herman Kriege, who as part of the Communist League had commissioned Marx and Engels to write the Communist Manifesto, joined a “stew of radical liberals, radical democrats, humanists, Christian evangelicals, socialists, feminists, disaffected Whigs, and formerly enslaved neo-abolitionists.”

By 1886 this mixture had grown into a movement that was able to mobilize 350,000 people in a nationwide May Day strike for the eight-hour workday. In Chicago, police fired on strikers, and at a subsequent protest in Haymarket Square a bomb was thrown at police, who fired indiscriminately on the crowd, killing at least four people. A wave of repression culminated in hundreds of arrests and the hanging of four men on flimsy evidence.

The “Haymarket martyrs,” most of whom had German immigrant backgrounds, became a symbol of American class struggle. Their “foreignness” was used to demonize working-class activism as an alien import, a political typhus that arrived on immigrant ships from Europe, carried, as one editorial writer put it, by “long-haired, wild-eyed, bad-smelling, atheistic, fanatical, reckless foreign wretches, who never did an honest hour’s work in their lives.”

The primary split in the working-class movement was between those who thought that change could come about only through violent revolution and those who sought to effect it through democratic means. The 1901 assassination of President McKinley by an anarchist from a Polish immigrant family reinforced the establishment’s fear of revolutionary violence, but Europeans weren’t just spreading anarchism and communism. In the years leading up to World War I and the Russian Revolution, the politics of social democracy were also making their way into American life.

In the Gotha Program, the platform adopted by the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) at its first congress in 1875, members pledged to endeavor

by every lawful means to bring about a free state and a socialistic society, to effect the destruction of the iron law of wages by doing away with the system of wage labor, to abolish exploitation of every kind, and to extinguish all social and political inequality.

Policies such as universal suffrage, free education, and shorter workdays were practical and popular, but Marx subjected the text to a withering and celebrated critique, calling it a “monstrous attack on the understanding” and a “compromise programme” for its “servile belief in the state, or, what is no better…a democratic belief in miracles.” The political schism between German Social Democrats and Communists only deepened during the twentieth century, with democratic socialists existing on a knife-edge between the two, trying to make the case for profound transformation without the violent overthrow of the state.

The German social democratic tradition was largely secular and anticlerical, which limited its appeal in deeply religious America, but there was another tradition, associated with the British labor movement, that drew its inspiration less from Marx than from the Sermon on the Mount and its promise that the meek shall inherit the Earth. Early British socialism was as much an ethical doctrine as an economic one, and was not focused on realizing the political demands of the working class. As Dorrien writes in a companion history of the European movement, Social Democracy in the Making (2019), “In the early going most Christian socialists were not even democrats…. They said socialism was a modern name for the unifying and cooperative divine order that already exists.”

In America the idea of a “social gospel” that sought to shape society as a Christian brotherhood swept across the country with an intensity that Dorrien likens to a third Great Awakening, following the waves of evangelical fervor that overtook the Northeast in the 1730s and again half a century later. The message was spread by firebrands like the Congregationalist preacher George D. Herron, whose heroes were Jesus and the Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini. “A true social democracy,” he declared, “is the only ultimate political realization of Christianity, and industrial freedom through economic association is the only Christian realization of democracy.” A distinctly American fusion of traditions was emerging that took in elements of Christianity, Marxism, and the individualistic ideals of Rousseau, Jefferson, and the French Revolution. Personal liberty was not in opposition to the common good, argued Herron; on the contrary, it could be attained only by people working together to build socialism.

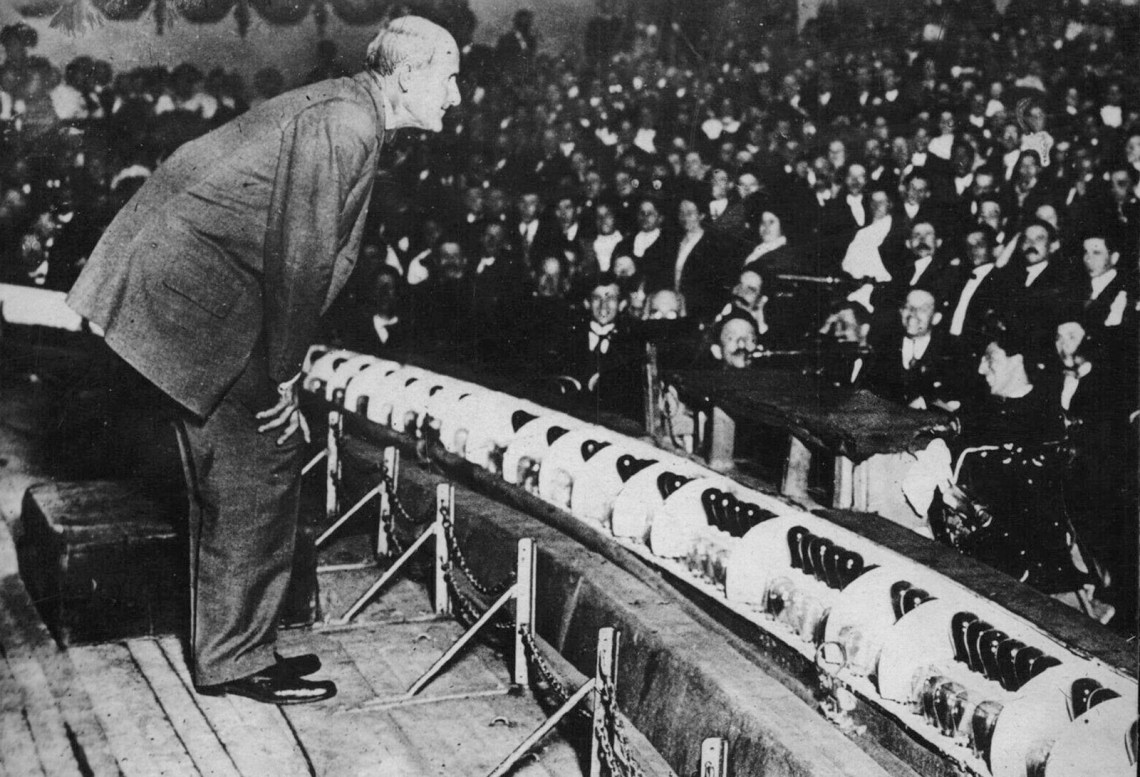

The high-water mark of American democratic socialism came in the years before World War I, when Eugene Debs, the charismatic leader of the Socialist Party of America, won 6 percent of the popular vote in the 1912 election. It should be said that this high-water mark was not particularly high compared to other countries. Debs’s party had 118,000 members in 1912. In the same year the British Labour Party had 1.9 million.

Advertisement

Yet socialist influence stretched beyond the ranks of those who took up formal party membership. Socialists were prepared to organize against poverty and exploitation at a time when workplaces were dangerous, the social safety net was nonexistent, and officials at all levels of government supported employers in the use of brutal tactics against workers seeking to improve their conditions. On the northern prairies, farmers were organized by the Non-Partisan League to oppose the predatory practices of banks and corporations.

In 1912 in Lawrence, Massachusetts, 20,000 mainly female textile workers with backgrounds in over fifty countries went on a successful two-month strike, becoming indelibly associated with the poetic demand for “bread and roses.” Socialist feminists were at the forefront of advocating for women’s suffrage, so much so that the link between feminism and socialism was a standard antisuffragist talking point. One tract decried “socialism, feminism, and suffragism” as “the terrible triplets.”

The socialist record on race was not so good. Though socialists played an important part in the foundation of the NAACP, there was a wing of the Socialist Party that didn’t want Black members, and the centrist position was to be “color-blind,” treating racism as a consequence of economic inequality. “We have nothing special to offer the Negro, and we cannot make separate appeals to all the races,” wrote Debs in 1903.

The Second International, the world socialist organization formed in 1889, resoundingly voted down a weaselly American proposal to ban “workers of backward races (Chinese, Negros, etc.)” on the grounds that they were driving down wages. But many in the American party still wanted to find a way to exclude Asian immigrants, considering them retarded in their “historical development” and hence incapable of being organized. They were opposed by the sole Black delegate to the 1904 and 1908 Socialist Party conventions, George Woodbey, a Baptist minister who had been born into slavery in Tennessee in 1854. At the 1908 convention he declared that “I am in favor of throwing the entire world open to the inhabitants of the world…. There are no foreigners, and cannot be.”

As the Socialist Party deliberated about whether it even wanted nonwhite members, the American Federation of Labor was happy to recognize segregated locals, which meant it was often impossible for Black workers to join a union, effectively excluding them from closed-shop occupations such as construction and metalworking. Many turned to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), a radical formation that spun out of the Socialist Party, advocating an uncompromising class-war politics. “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common,” stated the preamble to its charter. “Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the earth and the machinery of production, and abolish the wage system.”

The IWW actively recruited in communities the other groups ignored, organizing Black longshoremen on the Philadelphia docks and Japanese grape pickers in California’s Central Valley. In 1913 Mary White Ovington, one of the founders of the NAACP, wrote:

There are two organizations in this country that have shown they do care about full rights for the Negro. The first is the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People…. The second…is the Industrial Workers of the World.

In 1917 two events—America’s entry into World War I and the October Revolution in Russia—smashed the movement apart. Socialists opposed militarism, believed in international working-class solidarity, and in some cases were pacifists, but as American passenger ships were sunk by German U-boats it became hard to resist the eruption of patriotic fury. Socialist intellectuals, including Jack London, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and W.E.B. Du Bois, abandoned the Socialist Party’s antiwar line to stand with President Wilson.

Then the Soviets seized power in Petrograd. Debs called the October Revolution a “magnificent spectacle” and pronounced himself a Bolshevik “from the crown of my head to the soles of my feet.” Within a few months he was arrested and charged with sedition for an antiwar speech that was construed as interfering with the draft. After a legal battle that went to the Supreme Court, his conviction was upheld and he was sentenced to ten years in prison. It was the beginning of a wave of repression that also destroyed the IWW.

In the early morning of September 5, 1917, the FBI simultaneously raided every IWW office in the United States, removing documents, equipment, and furniture and effectively paralyzing the organization. Hundreds of members were put on trial, and its leader, Bill Haywood, fled to the Soviet Union after being framed for murder. In 1919, as Lenin announced the foundation of the Third International, or “Comintern,” dedicated to fostering revolution around the world, and more socialist leaders were arrested in the US, there was a split in the Socialist Party between those who wanted to transform the movement into an international Communist vanguard and a reformist “Old Guard” more attached to domestic electoral politics. A majority turned Communist, leaving behind a splintered democratic socialist rump.

During the Depression, the American Socialist Party struggled, reduced to a core of around 20,000 members, about a third of the size of the American Communist Party. Losing on the left to the glamour of World Revolution, they also struggled to distinguish themselves from the extensive social programs of Roosevelt’s New Deal. Many talented young organizers and intellectuals preferred to lend their energies to the New Deal rather than involve themselves in Socialist politics. At a public meeting in 1936 Norman Thomas, then the Socialist Party’s leader, denied that Roosevelt had carried out any Socialist platform “unless he carried it out on a stretcher.” In a widely circulated pamphlet, he tried to put a positive spin on FDR’s adoption of many of his policies: “Not only is it not socialism, but in large degree this State capitalism, this use of bread and circuses to keep the people quiet, is…a necessary development of a dying social order.”

With the Socialist Party moribund, many Depression-era leftists chose to work through unions. The passage of the Wagner Act in 1935 forced employers to recognize unions and engage in collective bargaining with them, sending union membership surging from 3 million in 1935 to 14 million in 1945. Then, with the end of World War II and a wave of strikes, a whiplash of reaction led to the Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which outlawed many of the organizing tools that had built union power over the previous decades: no more closed shops, no more secondary picketing, and a ban on unions contributing money to federal political campaigns. States were allowed to go further and prohibit union shops altogether by enacting so-called right-to-work laws aimed at breaking the power of the organized left.

The US never developed anything like the British Labour Party, in which unions and political groups come together to field candidates in national elections. The American Federation of Labor was never converted to socialism, and though industrial unions pushed for the formation of a political party in the period before World War I, they’d been unsuccessful. Taft-Hartley, which limited the scope of what unions could achieve, put an end to the dream of a political party representing the organized working class. Henceforth, as Dorrien writes, “the defanged labor movement belonged wholly to the Democratic Party.”

Some of the most enduring contributions of American socialism during the cold war were made through the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr. was not the “godless communist” of Bircher imagination but a man steeped in the tradition of the social gospel, as were his colleagues in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The northern movement was driven by socialists like Bayard Rustin, who had worked with Norman Thomas, and A. Philip Randolph, who had organized elevator operators and Pullman porters in the 1920s and 1930s. The Poor People’s Campaign, which the SCLC embarked on in 1968, shortly before King’s assassination, demanded an economic bill of rights for poor people that would include a living wage, access to land and capital, and “recognition by law of the right of people affected by government programs to play a truly significant role in determining how they are designed and carried out.”

In the 1960s the so-called New Left emerged “bristling with the idealism of privileged youth,” as Dorrien puts it, to challenge socialist orthodoxy with its embrace of personal liberation in the face of what Herbert Marcuse called the “technological rationality” of mass society. No longer was political struggle understood as a simple contest between the monolithic forces of labor and capital, and no longer was it “bourgeois individualism” to seek emancipation from the “system.” The most prominent American New Left organization, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), grew until, by some estimates, it had 100,000 members. “We would replace power rooted in possession, privilege, or circumstance by power and uniqueness rooted in love, reflectiveness, reason, and creativity,” affirmed its founding document, the Port Huron Statement.

Environmental campaigners, feminists, antiracists, and gay rights activists sought—and found—a politics that didn’t defer their concerns until after the class struggle was won. For some, the self rather than the mass became the primary site of political contestation. In one direction this led toward the politics of intersectionality, addressing the construction of the individual by social forces. In another, particularly among those influenced by the 1960s culture of personal growth, political identity became just one among many forms of self-expression, a turn to lifestyle that led them out of the left altogether, toward neoliberalism and the logic of enterprise and competition. In 1969 SDS imploded into ultraleftist factionalism and the terrorism of the Weather Underground. In all this, the concerns of the working class fell out of focus.

Profound changes were also taking place in the industrial society out of which socialism had emerged. New forms of labor led to new identities and allegiances. Much of organized labor supported the Vietnam War, and a split developed between the antiwar left and socialists who saw union power as the primary expression of the interests of the working class. In 1970 New York college students protesting the shootings at Kent State were attacked by construction workers chanting “USA all the way!” and “Love it or leave it!” This expression of working-class social conservatism was understood by many on the left as evidence of “false consciousness,” the theory that workers would act against their own interests because they had been misled into believing that the norms and values of the ruling class were beneficial to them.

Whatever its explanatory virtues, allegations of false consciousness have never endeared the theorists to the theorized, and the atmosphere of mutual antagonism between intellectuals and working-class conservatives was the harbinger of a political realignment. In 1950 the vast majority of highly educated Americans voted Republican. By the 1980s they were voting Democratic. There was no longer a party of the workers and a party of the bosses, but a fractured constellation of opposing elites—what Thomas Piketty has called, in Capital and Ideology (2020), the “Brahmin left” and the “merchant right”—each side trying to mobilize a racially and geographically divided working class whose participation in electoral politics was declining.

Then came the Reagan program of tax cuts, aimed at undoing the New Deal and curbing the bureaucratic power of the administrative state. Dorrien dutifully catalogs the splits and reconfigurations of 1980s American socialism, but it’s a low-stakes story of politically marginal groups struggling to react to enormous global and economic shifts. As end-of-history technocracy triumphed, socialism appeared outmoded, a form of sentimental attachment to the tribal politics of the past.

Dorrien describes the Clinton period as “wilderness years of intense demoralization on the left.” He has little to say about the involvement of socialists in the 1990s antiglobalization movement, but lists various positive currents, from the liberation theology of Cornel West to the rise of Black feminism. After September 11 the DSA was active in the opposition to the Iraq war, but Dorrien does not write about the unchecked expansion of the security state, and he focuses on economic policy in his discussion of the reconfiguration of American society during the heyday of neoliberalism, missing the philosophical promotion of individualism and the erosion of group solidarity that has proved so challenging to socialist politics.

He tracks the mixed results of the emergence of culture as a terrain for socialist political activism: as the culturalist left retreated from class struggle, the Democratic Party began to sideline redistributive policies in favor of a politics of representation or recognition, promoting what the philosopher Nancy Fraser calls “parity of participation” in social affairs as a solution to disadvantage. While this liberal form of “identity politics” has won victories, particularly in the field of LGBTQ rights, it often takes on the same quality of pageantry as the evergreen Republican culture war, a performance of virtue that does not seem to be intended to change material conditions. The bank supports gay pride, legislators wear kente cloth as they take a knee, but the poor and marginal will stay poor and marginal.

“Nobody got famous on market socialism,” Dorrien writes, wryly, and he is resolutely unmodish in the story he chooses to tell, but the version of the socialist left that emerges from American Democratic Socialism is one that deserves more attention. The Reagan tax cuts increased average household income, but most of those gains were taken by those at the top. As this disparity has compounded over forty years, the economic position of America’s lower classes has collapsed. According to figures from the World Inequality Database, between 1960 and 1980 the bottom 50 percent claimed around 20 percent of national income. That share has now almost halved to 13.6 percent, while the share of the wealthiest 10 percent has almost doubled, from 10 to 19 percent. During the pandemic, those at the very top have seen their wealth surge. American billionaires are now collectively 70 percent richer, an additional accumulation of $2.1 trillion. Every measure of wealth and income tells the same story. The question posed by socialism—how to organize the economy to produce prosperity for all—seems newly relevant.

Since the rise in inequality threatens to return us to the social relations of the Gilded Age, maybe it shouldn’t come as a surprise that we are seeing a socialist resurgence. DSA membership is now edging toward the size of the Socialist Party of the Debs era. Industrial disputes are also on the increase, spurred by a tight labor market and a feeling that pandemic sacrifices aren’t being properly rewarded. John Deere workers, Alabama miners, and graduate students at Ivy League universities are among the groups that have gone on strike. Socialists have taken part in campaigns for economic justice, such as the fight for a fifteen-dollar minimum wage and the successful New York taxi drivers’ hunger strike for relief from medallion debt, and have assisted in the bitter struggles for unionization taking place at high-profile companies with liberal brands like Amazon and Starbucks.

The pandemic has ruthlessly exposed the failures of a society that has rejected many forms of solidarity, preferring to conceive of itself as a loose network of entrepreneurial individuals. The chaos and ineffectiveness of the public health system, the precariousness of “gig economy” jobs, the disastrous coupling of employment and access to health care, the unaffordability of housing, and the insecurity of globalized supply chains all, in different ways, remind us of the “embeddedness” of markets in collective life, and the embeddedness of that collective life in the ecosystem of a warming planet.

Piketty warns that redistribution after the fact, through taxation, will be inadequate to address the “massive distortion in the distribution of primary incomes” that characterizes contemporary American society. To address this imbalance, he writes,

one also needs to think about policies capable of modifying the primary distribution, which means making deep changes to the legal, fiscal and educational system to give the poorest people access to better paying jobs and ownership of property.

To be credible, such policies must not be a return to twentieth-century central planning. If redistribution is to be undertaken via sharply progressive taxation, and in particular the taxation of inherited wealth, it cannot be allowed to devolve into the expropriation of one elite to create a new nomenklatura. The scale of the technical task twenty-first-century democratic socialism sets itself is only matched by the political task of persuading Americans that the desire for bread and roses does not lead to the gulag.