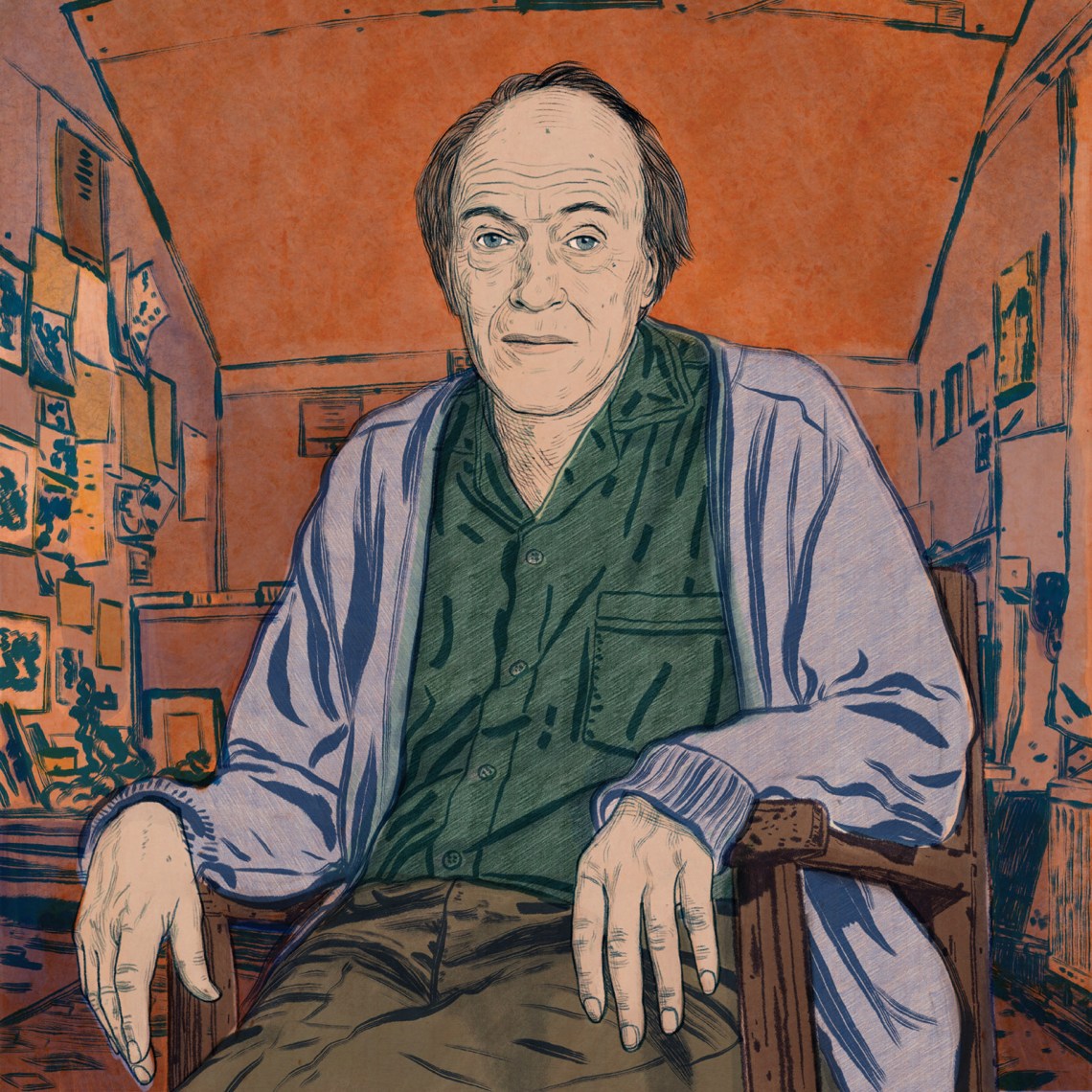

1.

“Bitch”—this is the title of the first short story in the July 1974 issue of Playboy. Its author is Roald Dahl, famous for the children’s books James and the Giant Peach and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. The story’s plot is a plot, a conspiracy by an English rake and raconteur, Oswald Cornelius, to remove the corrupt American president from office by inducing him to rape a woman during a live television broadcast. How? By having him inhale a top-secret perfume called Bitch, a fragrance made from sexual stimulants so intoxicating that any man who smells it will proceed to have wild and possibly—no, probably—nonconsensual sex with the first woman he sees. “That was exactly how I had to have him. He had fallen into many a sewer and had always come out smelling of shit,” Oswald reasons. “A man who rapes a woman in full sight of twenty million viewers across the country would have a pretty hard time denying he ever did it.”

The rape is to take place at a dinner hosted by the Daughters of the American Revolution, with the intended victim, Mrs. Elvira Ponsonby, presiding over the ceremonies. The president (unnamed but clearly based on Nixon) will be exposed to the perfume by means of a time-release capsule hidden in a corsage Oswald will deliver to Mrs. Ponsonby hours beforehand, claiming that it is a gift from the president. He knocks on her hotel room door; the woman who opens it is the most enormous woman Oswald has ever seen, a giant draped in the stars and stripes of the American flag. The twist is so obvious it is impossible to spoil. As Oswald attempts to pin the corsage to Mrs. Ponsonby’s patriotic bosom, the capsule punctures. Overwhelmed by the scent, he loses consciousness. When he awakes, he finds himself transformed:

When I came round again, I was standing naked in a rosy room and there was a funny feeling in my groin. I looked down and saw that my beloved sexual organ was three feet long and thick to match. It was still growing. It was lengthening and swelling at a tremendous rate. At the same time, my body was shrinking. Smaller and smaller shrank my body. Bigger and bigger grew my astonishing organ, and it went on growing, by God, until it had enveloped my entire body and absorbed it within itself. I was now a gigantic perpendicular penis, seven feet tall and as handsome as they come.

It goes without saying that “Bitch” is a rape joke. Published one week before the justices of the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in United States v. Nixon, and one year after the CIA was rumored to have helped overthrow President Salvador Allende in Chile, it is also, more obliquely, a joke about the futility of espionage and the pleasures of failing to undermine democracy. Determined to bring down Tricky Dick, Oswald grows up, up, up into an even trickier one, lusty and fleet-footed. The star-spangled maiden, the icon of Republican womanhood whom he towers over, is debauched with joy and vigor, a delirious virtuosity that far surpasses Nixon’s clumsy attempts to screw the American public.

On my first read, the punch line of “Bitch” seemed to be that Mrs. Ponsonby had liked being raped. “I don’t know who you are, young man,” a voice says as Oswald flees the room in panic. “But you’ve certainly done me a power of good.” On my second read, I was struck by the Englishness of the phrase “a power of good,” which no American would use. Now that voice, shot through with self-congratulation, seemed to come from within and beyond Oswald all at once. It was a voice that announced on behalf of Mrs. Ponsonby: “See? What did I tell you? She wanted it.”

The pleasures of making it big and making it small and not noticing or caring who gets hurt in the process—this is the gimmick on which nearly all Dahl’s children’s books turn, the gimmick that reveals the hollowness at their center. It begins with James and the Giant Peach (1961), his first serious attempt at children’s fiction, in which a peach crushes James’s spinster aunts and rolls off with him and a host of giant insects inside. It is no longer possible for me to read “Bigger and bigger grew the peach” without hearing its echo, thirteen years later, in “Bitch.” Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964) squeezed, shrank, and stretched its spoiled children, their punishments doled out by the Oompa-Loompas—described in the first British edition as a race of “amiable black pygmies” imported to England from “the very deepest and darkest part of the African jungle” by Willy Wonka, who invites them to work as chocolate makers in exchange for an endless supply of cacao beans.

Advertisement

Its inferior sequel, Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator (1972), an extended mockery of Nixon’s Space Shuttle program, places Charlie, his family, and Willy Wonka in orbit, where magical anti-aging pills cause Charlie’s greedy, cantankerous grandparents to shrink into newborns. The bigness of the Big Friendly Giant is advertised in the title of The BFG (1982), as is his kindness to his charge, the orphaned little Sophie. A pacifist and vegetarian, a slow, simple collector of dreams, the BFG hands over his entire species to the queen of England, who orders a force more powerful than the giants, the British army, to extract them from their native land and imprison them in a deep pit in London. Here, in a modern Tartarus, they serve as a lucrative tourist attraction and a convenient mechanism for disposing of the bodies of drunks and other miscreants.

The books that are not gleefully Victorian, with their orphans and prisons and imperialist nostalgia, are more fabulist, layering some anthropomorphic twist onto their manipulations of size. In The Magic Finger (1966), shrinkage is the punishment suffered by a family of hunters, who are turned into small birds and shot at by the birds whose babies they have gunned down. The hideous couple in The Twits (1980), Mr. and Mrs. Twit, are tricked into standing on their heads by the animals they have tortured; they disappear after contracting a case of the “dreaded shrinks,” their heads folding into their shoulders, which fold into their trunks, which fold into their boots. George’s Marvellous Medicine (1981) opens with nine-year-old George caring for his vile grandmother, who accuses him of “growing too fast.” “Boys who grow too fast become stupid and lazy,” she scolds him. The medicine he makes to punish her sends her shooting through the roof of the house, before shrinking her into nonexistence; by contrast, it makes the animals on his family’s farm grow big and fat and profitable to slaughter and sell.

Perhaps inspired by “Witches’ Brew,” a report from a witchcraft convention that followed “Bitch” in Playboy, Dahl set The Witches (1983) at a witchcraft convention in southern England. The witches, who speak in vaguely German accents, turn little boys into mice, their skin growing “smaller and smaller” and “tighter and tighter” until their clothing disappears and fur sprouts in its place. In the last book published before his death, Esio Trot (1990), an elderly man in love with his young, buxom neighbor, the owner of a tortoise, presents her with an incantation to help the tortoise grow faster: “ESIO TROT, ESIO TROT!” (She does not seem to realize this is “tortoise” backward.) Secretly, when she goes to work, he replaces her tortoise with an incrementally larger one every week over the course of two months. Bigger and bigger grows her tortoise, until she is so overwhelmed with ignorance and gratitude that she marries her neighbor.

Reading Dahl’s books to my children in swift succession over the past few months has reminded me of Samuel Johnson’s complaint about the comedy of Gulliver’s Travels: “When once you have thought of big men and little men, it is very easy to do all the rest.” Easy it may be, but the results are very wide-ranging indeed. Dahl’s fictions of scale are the stupidest and crudest I have encountered. They have none of the unearthly enchantments of Grimms’ Fairy Tales or Diana Wynne Jones’s Howl’s Moving Castle; none of the madcap philosophical sophistication of Norton Juster’s The Phantom Tollbooth or Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, whose title character is forever stretching out or shutting up like a telescope; none of the intricate, if somewhat tiresome, world building of L. Frank Baum’s Oz books or Enid Blyton’s The Faraway Tree; none of the genuine ethical and political complexity of the three greatest children’s authors, Edith Nesbit, C.S. Lewis, and Edward Eager. With few exceptions, size, in Dahl’s imagination, is nothing more than a proxy for force. Largeness indicates the power to manipulate and coerce; smallness indicates vulnerability to punishment and annihilation that must be overcome through trickery. Even his happiest endings left my children listless and a little depressed, as if they intuited that what had seemed at first to be the pursuit of justice in an unjust world was nothing more intriguing than a game of bloody knuckles, a theater of schoolboy cruelty.

There is, of course, nothing inherently wrong with cruelty in art; in children’s literature, it has its place, particularly when it responds to the physical and emotional cruelties inflicted upon children, among the most powerless and casually brutalized creatures in the world. Yet the sadism of Dahl’s plots and the grotesquerie of his characters contain not a single germ of critical self-reflection, not one gesture of liberation, not a drop of pity or compassion, no matter how begrudgingly they may be tendered, in life as in fiction. The cruelty of his villains begets a reciprocal cruelty in their victims. He makes his children small then big; he makes his adults big then small; and he traps his shape-shifters and his young readers in a fun house of dirty, depthless mirrors. This is how one enters into “the marvellous world of Roald Dahl,” as the BBC called it in a 2016 documentary celebrating his enduring contributions to British culture.

Advertisement

2.

Pull back the curtain on this world and you will find its creator, a man who, by many accounts, lived much of his life feeling like a small, fretful, persecuted boy, even though he was, by midcentury, a fighter pilot turned spy, a spy turned playboy, and from the 1960s on a very wealthy, very popular writer. The enduring irony of Dahl’s career is that children’s literature was the only corner of the literary marketplace where he could make it big and stay big. He had tried his hand at adult fiction, writing stories about his wartime exploits for The Saturday Evening Post in the 1940s, gothic tales about unhappy marriages for The New Yorker in the 1950s, screenplays for the Hollywood studios in the 1960s. He had dreamed of being Ernest Hemingway. He ended up a third-rate Shirley Jackson, writing lurid fantasies about rape and wife swapping for Playboy and the screenplay for You Only Live Twice, the Bond adaptation that ruined Bond adaptations. Only then could he commit fully to children’s literature, where he thrived financially. His preoccupation with size bears the ambivalent imprint of his successes and failures—the anxieties of a man who appeared, from one angle, too big to fail, and, from another, too small to take seriously.

All this is excellent stuff, marvelous stuff, for the biographers who have been sniffing around Dahl’s life and work since his death in 1990. The first biography, Roald Dahl by Jeremy Treglown, a professor of English and former editor of The Times Literary Supplement, was published in 1994. It was responsibly sourced and thus appropriately skeptical of Dahl—of the charming, compulsive self-mythologization of his memoirs; of his racism, his sexism, his anti-Semitism, and, above all, his tyrannical streak, his arrogance and bluster. Donald Sturrock’s authorized biography, Storyteller, which appeared nearly two decades later, did what many authorized biographies do that arrive late on the scene: damage control. Its tone was, in the words of reviewers, “strained,” handling his marriages and mannerisms with a delicacy that bordered on whitewash. Even so, it gave some sense of the man himself, arranging scenes that demonstrated his sometimes sinister, sometimes charismatic extravagance: the casual authority with which he cracked a lobster’s claw at dinner on his estate while decrying the value of biography to his future biographer.

In comparison to both, Matthew Dennison’s Roald Dahl: Teller of the Unexpected is thin gruel. It is a stylish but curiously pointless biography, the kind that neither uncovers anything new nor casts what was already known in an interesting light. Dahl’s children’s books are not read so much as mentioned, each allotted one or two dutiful sentences noting its publication and reception. The only institutional archive consulted is the Roald Dahl Museum and Story Centre, whose offerings appear to have been organized to present the writer in the most favorable light. The most scandalous tidbits come from Treglown’s and Sturrock’s books, although quotes and excerpts from letters are pared and twisted to downplay Dahl’s malice, his boorishness.

It is worth noting that Dennison is mostly a biographer of grand English ladies—Princess Beatrice, Queens Victoria and Elizabeth II, Vita Sackville-West—and one cannot help but wonder if his latest is a chummy attempt to redeem a beloved British cultural export now that the royals have proved themselves to be beyond redemption. “‘Grandiosity, dishonesty, and spite’ play no part in the writing,” Dennison claims, dismissing Dahl’s critics. Theirs “is a selective view, countered by testimony to Roald’s charm, kindness and generosity.” This is biography as public relations.

Part of the challenge is that Dahl told much of his story himself, beginning with his memoir Boy (1984), which narrates the first eighteen years of his life with little concern for getting the facts straight. Yet one would rather read his stories, however fanciful, than incurious or pedantic paraphrases of them. The indignities of his life are the indignities of the British bourgeoisie, although with a greater share of domestic tragedy than most. He was born in 1916 to a wealthy Norwegian shipbroker and his second wife, the youngest son in a family of seven children. When he was three, his older sister died of appendicitis, and his father died weeks later, some said of a broken heart. In accordance with his father’s dying wish, his mother sent him to the finest grammar schools. There he was regularly beaten by the teachers and older boys—hazed, caned, mocked for his tears. Dahl wrote that “a boy of my own age called Highton was so violently incensed” after one of Dahl’s beatings “that he said to me before lunch that day, ‘You don’t have a father. I do. I am going to write to my father and tell him what has happened and he’ll do something about it.’”

It is strange that none of his biographers make much of the loss of his father, beyond pointing out the obvious, that his children’s books often feature orphans or children with cruel, neglectful parents. Biography is not psychoanalysis, of course, but when the symptoms float so close to the surface, it makes little sense not to cast one’s net. For he prided himself on growing bigger than his tormentors, so big that he didn’t need a father around to “do something about it.” He shot up to an astonishing six foot six, with pale blue-gray eyes, a high forehead, and a handsome jaw; a solidly middle-class English boy at once fascinated and repulsed by the English institutions his dead father had extolled, with a noticeable dependency on the admiration of his mother and sisters.

Is it any surprise that he was drawn to novels about heroism and conquest, to visions of a hard, solitary masculinity that brooked no beatings, no insults? That he turned his back on the effete intellectualism of Oxford and Cambridge and headed to Dar es Salaam for Shell Oil? He wrote about his experiences, then, in the deplorable idiom of all colonialists. “Sometimes there is a great advantage in traveling to hot countries, where niggers dwell,” he advised in an essay before departing in the autumn of 1938. “They will give you many valuable things.” He was happy to discover that he was the perfect colonial administrator, cool and affable and instinctively comfortable with the power he wielded over his African and Indian clerks. He wore a slim white suit to work, and he knew he wore it well. The meekness of his subjects made him feel “like a bloody king,” he wrote to his mother.

When the war began, he was recruited as a fighter pilot by the RAF. He imagined himself a daredevil, shooting, dive-bombing, cheating death in the open skies from his hot, cramped cockpit. One gets a sense of the thrill and agitation in his best collection of stories, Over to You: Ten Stories of Flyers and Flying (1946). Not included in it is “Shot Down Over Libya,” which recalls the crash in the desert that fractured his skull, wrenched his back, and drove his nose so far into his head that he appeared to have no nose at all during the two months he spent convalescing in a hospital bed in Alexandria. After he recovered, he flew for a week and a half over Greece, ten days of aerial combat and five confirmed hits of German planes he’d seen gunning down Greek children with a dispassion he would dramatize in his story “Katina.” “We really had the hell of a time in Greece,” he wrote to his mother, before returning home to her in 1941. “It wasn’t much fun taking on half the German Air Force with literally a handful of fighters.” “I flew down the steps of the bus straight into the arms of the waiting mother” is the closing image of Going Solo (1986), his second autobiographical book.

He joined the British embassy in Washington, D.C., in 1942 as an assistant air attaché, one of the many grammar school boys eager to try his hand at espionage, trading sex and secrets with the rich and famous, while selling his war stories to The Saturday Evening Post. In any given month, the first weekend might find him at Hyde Park or the White House alongside the First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt; the second at the poker table, losing the thousand dollars he claimed to have been paid for a story to Senator Harry Truman; and the third and fourth in the bed of Clare Boothe Luce, an asset he boasted about cultivating. He lived with the advertising mogul David Ogilvy, drank with Isaiah Berlin and Ian Fleming, “slept with everybody on the East and West Coasts that had more than fifty thousand dollars a year,” marveled Antoinette Marsh, daughter of the newspaper magnate and oil tycoon Charles Marsh.

He befriended father figures who were larger than life, men immortal in deed if not body: Marsh; the British ambassador, the 1st Earl of Halifax; the Disney brothers, who, for a time, planned to turn Dahl’s short story “Gremlin Lore,” about the imps who sabotage fighter pilots’ planes, into an animated feature film. Dahl liked to present his accomplishments to all of them for approval. “I am all fucked out,” he told a friend of his weekends with Booth.

That goddamn woman has absolutely screwed me from one end of the room to the other for three goddamn nights. I went back to the Ambassador this morning, and I said, “You know, it’s a great assignment, but I just can’t go on.”

Dahl met his first wife, the actress Patricia Neal, at a dinner party in New York. He spent the meal ignoring her, then called her the next day: “Jolly glad to find you home. How about some supper with me?” Her recollections of their courtship and marriage are considerably more entertaining and disturbing than his biographers can verify. Scraps of their first date are preserved in her memoir, As I Am:

He made sure I was aware that he was taking me to one of the finest Italian restaurants in New York. He knew the owner, who was John Huston’s father-in-law. He was acquainted with just about everybody. And he was interested in everything. He spoke of paintings and antique furniture and the joys of the English countryside. He was as charming that evening as he had been rude the first time we met. I remember his taking a sip of wine and looking at me for a long moment through the candlelight.

“I would rather be dead than fat,” he said.

Not long thereafter, she learned that “one of Roald Dahl’s great assets was his desire never to leave a female unfulfilled,” and while this, and the prospect of a household full of children, seemed to be enough for her, her crowd of New York writers and actors were unimpressed when he proposed marriage with a ring on credit from one of his wealthier friends. (He had recently lost his entire inheritance on a bad stock tip.) “I think he’s a very silly dull fellow,” wrote Dashiell Hammett, one of several people who had told Neal flat out that accepting Dahl would be a grave error. “The ring isn’t bad looking, though, and I told her I was glad she was getting that out of it because she didn’t look as if she was getting much else.”

“Deliberate is a good word for Roald Dahl,” Neal later reflected. “He knew exactly what he wanted and he quietly went about getting it.” His marriage, however, does not appear to have given him what he wanted. How could it have, when he had married a woman who was bigger than him—more famous, wealthier, unwilling to wait on him hand and foot as she soon learned his mother had? His insecurity made him high-strung, implacable. Neal tried to appease him first by giving him control over her bank account, then, in 1954, by moving with him to England, where she and his mother pooled their money to purchase for him a country house on the edge of Great Missenden, just outside London. Their home was called Gipsy House, and the family that Dahl and Neal created in rapid succession—four daughters and a son—spent the next decade crisscrossing the Atlantic, chasing Neal’s film and theater roles in New York, living off her steady stream of money while he tried to write.

It is difficult not to read the books that follow as testifying to the unhappiness of the union. The short stories from the late 1940s to 1970s collected in Someone Like You, Kiss Kiss, and Switch Bitch are a mix of horror, satire, and smut—memorable, if they are memorable at all, for their possibly campy, possibly misogynistic twists. A pleasant elderly landlady turns out to have a nasty habit of poisoning her young male lodgers and turning them into taxidermied figures. Two neighbors sneak into each other’s houses to have sex with each other’s wives under the cover of dark; the next morning, their wives reveal that last night was the first time they ever felt sexually satisfied. For a short period of time, Dahl had a contract with The New Yorker, but it was allowed to lapse in 1960, when Katharine White, the magazine’s fiction editor, simply stopped replying to his submissions.

During these years, Dahl appears to have evolved into a finicky and obsessive father—he was “a very maternal daddy,” Neal claimed—and it is as a parent that he cuts the most sympathetic figure. Some of this sympathy is won from the suffering of his five children. His infant son, Theo, was in his stroller when it was struck by a taxi, and the baby endured one surgery after another to repair his crushed skull. In an act of genuine heroism, Dahl worked with his son’s neurosurgeon and a hydraulic engineer to invent a valve that would drain excess fluid from the brain. Several months after his son started to recover, his oldest daughter, Olivia, died of measles at the age of seven, a horrific echo of his sister’s death. Dahl had written his first serious piece of juvenile fiction, James and the Giant Peach, which he dedicated to her; his second, a draft of a book called Charlie’s Chocolate Boy, was written for Theo just before the accident. “What the hell am I writing this nonsense for?” he wondered. Now there was no chance of writing, nonsense or otherwise. He drank, took barbiturates, and could not produce anything. Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, published in the US in 1964, failed to attract any UK publishers until several years later.

At the start of 1965, Neal suffered two brain aneurysms while pregnant with their fifth child. She was left without speech, paralyzed, and morbidly depressed by what looked to be the end of her career. Her sudden incapacitation seems to have pulled Dahl out of his despair. “Unless I was prepared to have a bad-tempered, desperately unhappy nitwit in the house,” he said, “some very drastic action would have to be taken at once.” He instituted a punishing schedule for speech therapy and prophesied her miraculous recovery, first in an authorized biography of the couple called Pat and Roald, then in press releases he issued to the tabloids. As their expenses skyrocketed, he took on more screenwriting gigs—You Only Live Twice, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, and the film adaptation of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. One can imagine him surveying his industry and ventriloquizing, on behalf of his speechless wife, the same admiration his character Mrs. Fox expresses for her vain but resourceful husband in Fantastic Mr. Fox (1970): “I should like you to know that if it wasn’t for your father we should all be dead by now. Your father is a fantastic fox.”

Dahl’s success as a children’s author came almost overnight in the 1970s, when the accumulated royalties from James and the Giant Peach and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory turned him into a millionaire and prompted reprintings of his other children’s books by Knopf in the US. It also made him considerably more difficult to deal with—pushy, boastful, and, as Treglown implies, simultaneously lazy and demanding. He started to recycle old ideas, beginning with Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator. The Magic Finger, George’s Marvellous Medicine, and The Twits are versions of the same story, with the repulsiveness of the characters ratcheted up in each iteration. He was, according to his publishers and editors, a nightmare. “You have behaved to us in a way I can honestly say is unmatched in my experience for overbearingness and utter lack of civility,” one editor wrote to him. “I’ve come to believe that you’re just enjoying a prolonged tantrum and are bullying us.” According to Treglown, the severance of the relationship led everyone at Knopf to stand on their desks and cheer.

He left Neal in 1983 for Felicity Crosland, a set designer he met on a Maxim coffee commercial Neal had shot in 1972. He and “Liccy” had been involved for over a decade. His daughter Tessa had discovered the affair in the late 1970s—“You’ve always been a nosy little bitch,” she remembers him shouting at her—but he pursued it while Neal looked the other way, up to the point when her willful blindness proved intolerable to her. The affairs of great artists are moderately interesting, especially if they provide grist for the mill. The affairs of lesser ones are, well, less so. There is little about Dahl’s divorce or remarriage that merits lengthy description, save how strenuously he and Liccy labored to present their marriage as his first and only one in the British tabloids. Everyone seemed to have consented to the fantasy that he was happier with her and that the major book he completed before his death, Matilda (1988), was touched by this happiness. But what use was such happiness when he was aged and ailing and brimming with meanness? His children were in various states of disrepair, addicted to drugs and alcohol and bad behavior. His art, if one could call it that, was increasingly a source of struggle. There is, across all the biographies, a strange sense that, for Dahl, life did not grow bigger and richer, but smaller and shallower—that, by the end of it, he had shrunk into himself, rather like Mr. and Mrs. Twit.

3.

If there is a thesis of sorts to Dennison’s biography, it is that Dahl’s noblest ambition was “an evangelical zeal for turning children into readers.” The test case for it would have to be Matilda, the best of Dahl’s books. My most vivid memory from childhood is the envy I felt for Matilda Wormwood and her apparently effortless genius as a reader—a genius that not only propelled her to the top of her class but gave her the extrasensory powers by which she could punish her hostile parents and rid her school of its tyrannical headmistress. I know I first read Matilda when I was seven, because I remember calculating the difference between how old I was when I read Matilda and how old Matilda was when she learned to read—“by the time she was three”—and the bitter, despairing feeling that came over me when I was forced to acknowledge how unexceptional my own accomplishments were. I remember, too, that I made my mother take me to our local bookshop so that I could purchase the cheapest, flimsiest copy of each book Matilda had read in the public library by the time she was five:

Nicholas Nickleby by Charles Dickens

Oliver Twist by Charles Dickens

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Tess of the D’Urbervilles by Thomas Hardy

Gone to Earth by Mary Webb

Kim by Rudyard Kipling

The Invisible Man by H.G. Wells

The Old Man and the Sea by Ernest Hemingway

The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck

The Good Companions by J.B. Priestly

Brighton Rock by Graham Greene

Animal Farm by George Orwell

(Not finding the Webb, the Priestly, the Kipling, or the Greene in stock, I purchased The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo. I believed then, as I sometimes still do, that any book first written in French counted for four books written in English.)

For years, I struggled to read these novels. I understood very little of them, although I can remember deriving feelings of acute pleasure from some (Austen, Brontë, Dickens, Hardy) and boredom from others (Orwell, Hemingway), and I can remember setting some aside with sharp pangs of frustration (Faulkner, Hugo, whose interminable novel I still have not finished). I must have read Matilda a dozen times between the ages of seven and ten, and each time I felt my envy gnawing away at my absorption, my instincts of enjoyment, until reading about her brilliance became a compulsion and an agony. I am being dramatic, of course, but children are dramatic and frequently self-absorbed readers. They can have trouble seeing past the shadows they cast on the page.

It was only in reading Matilda to my own children nearly three decades later that I had a startling and, frankly, ludicrous realization: there is no child at the center of this book. As a character, Matilda has no inner life, no desires, no longings, not even for the lost affections of her horrendous parents. She barely speaks, and when she does, what she has to say is unremarkable and even charmless. She is not a heroine; she is not even a proper person. In her, the invisible act of reading assumes its visible form, the terribly fragile form of a young, unloved girl whose powers of thinking and feeling are fueled by her rage, her desire to be seen and heard and treated as worthwhile in a world that values neither depth of thought nor intensity of feeling. The description of these powers in Matilda gets closer than most fiction to capturing the feeling of reading: how it joins mind to eye to hand; how it acts as a kind of current electrifying the senses, willing self-abandonment and self-transcendence:

A sense of power was brewing in those eyes of hers, a feeling of great strength was settling itself deep inside her eyes. But there was also another feeling which was something else altogether, and which she could not understand. It was like flashes of lightning…. It felt as though millions of tiny little invisible arms with hands on them were shooting out of her eyes.

Matilda’s smallness thus differs from ordinary human vulnerability. It measures the cultural fragility of reading literature in a world that refuses to protect or nourish it. This is the hidden meaning of the book’s opening chapter, which still stands, in my grown-up mind, as the most moving first chapter in children’s literature. After some swipes at children whose parents overestimate their talents—more pleasurable now that I regularly interact with other parents—Dahl introduces us to the book’s central conflict, between the desire to read and the belittlement of this desire by forces that no single reader can subdue on her own. Matilda asks her father for a book:

“Daddy,” she said, “do you think you could buy me a book?”

“A book?” he said. “What d’you want a flaming book for?”

“To read, Daddy.”

“What’s wrong with the telly, for heaven’s sake? We’ve got a lovely telly with a twelve-inch screen and now you come asking for a book! You’re getting spoiled, my girl!”

What is a child to do? Mike Teavee, from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, would plunk himself down in front of the idiot box. Four-year-old Matilda marches herself straight to the public library. The librarian, Mrs. Phelps, is pictured in Quentin Blake’s illustrations as a colossus bestride the pale, wondering girl.* Mrs. Phelps is a model of benevolence and tact, one of only two good and true adults in the book. She asks and wants nothing from Matilda—only guides her to a reading chair and to a copy of Great Expectations. Blake’s illustration portrays her sitting in a gigantic chair, with the great frame of a book occupying the whole of her tiny lap. The reader half expects her to be leveled and crushed by literature, but this is precisely the illusion from which the illustration gains its pathos. The physical littleness of the girl is not opposed to, but equivalent to, the cultural littleness of her beloved objects, the nineteenth- and twentieth-century novels dismissed by those who cannot read them, have not read them, or refuse to read them.

The two forces working to keep literature small in Matilda are, first, the philistinism of the British middle class and, second, the bureaucracy of their schools. Mr. Wormwood represents the first. He is a lying, cheating, money-laundering used car salesman, a dandy and an idiot. The sight of his daughter engrossed in her book fills him with rage: “She kept right on reading, and for some reason this infuriated the father. Perhaps his anger was intensified because he saw her getting pleasure from something that was beyond his reach.” She is reading John Steinbeck’s The Red Pony, and her father’s resentment is, not surprisingly, tinged with anti-American xenophobia. “If it’s by an American it’s certain to be filth,” he snarls. “Go and find yourself something useful to do.” He starts to tear pages out of her book, sending them flying every which way, and in Blake’s illustrations, these pages appear to have faces on them that are crumpled in pain. Would it be a stretch to insist that the body of the book stands in for the body of the child? That it is his daughter’s spine Mr. Wormwood wants to crack, and not the spine of a novel?

The violence against the book is merely symbolic, but it finds its physical corollary in Agatha Trunchbull, the headmistress known as “the Trunchbull,” who represents the bureaucratic overreach of the British school system. Shouldering her way into classrooms, telling teachers how to do their jobs, abusing students, throwing them in the “Chokey” for offenses real and imaginary, she rules with a divine indifference to the logic of the classroom. Like many administrators at British universities today, she does not have a background in education. She was an Olympic hammer thrower, capable of claiming no expertise other than moving a blunt object from here to there. The great secret to the Trunchbull’s success as an administrator, which Matilda rightly identifies, is to make her discipline of teachers and students so shockingly disproportionate and senseless that it beggars belief: “Never do anything by halves if you want to get away with it. Be outrageous. Go the whole hog. Make sure everything you do is so completely crazy it’s unbelievable.”

In a world shaped by the philistine and the bureaucrat, what hope is there for literature? For Matilda, the answer comes in the form of a character more fragile than she is: Miss Honey. In her, the spirit of learning is wedded to the spirit of play, to a natural and ethereal beauty that seems immune to the dreary practicalities of the adult world. Indeed, a teacher like Miss Honey has precious few resources with which to maneuver in it. She didn’t graduate from a university but from a vocational school, a teacher’s college in Reading. She lives in a tiny cottage on the outskirts of the city with no plumbing or heat, eating crusts of bread with margarine. “Are you poor, Miss Honey?” Matilda asks. “Yes,” Miss Honey answers. “Very.”

Miss Honey’s confession of her poverty made no impression on me as a child, but it moves me deeply as an adult. It is as an adult that her existence reminds me of the opening chapters of Raymond Williams’s The Country and the City. The scenes set near her cottage, where she recites the opening stanza of Dylan Thomas’s “In Country Sleep” to her rapt pupil, summon Williams’s description of the pastoral as a “sense of a simple community, living on narrow margins and experiencing the delights of summer and fertility the more intensely because they also know winter and barrenness and accident.” The prudence, the purity, of Miss Honey’s life is a response to the threat of loss and eviction that afflicts farmers and teachers alike; the Trunchbull, we learn, is Miss Honey’s aunt and, since the death of Miss Honey’s father, has kept her niece in a state of indebtedness. She is held hostage by a monster who is both administrator and rentier, a monster who grows bigger and bigger by draining of their will, their spirit, those who do the daily work of reading and writing.

It is Matilda who frees Miss Honey from her dependency, using her telekinetic powers to write a message to the Trunchbull on the blackboard:

Give my Jenny her wages

Give my Jenny the house

Then get out of here.

If you don’t, I will come and get you.

These lines restore Miss Honey to her ancestral home, endow her with a sense of autonomy as a teacher and bargaining power as a worker, and make it possible for her to adopt Matilda. Yet at what cost? There is a curious schism in the book between Matilda’s reading and her writing, which we see her do exactly once, and without using her hands. The sentences she writes have all the sophistication of a kindergarten primer. True, what they lack in poetry or punctuation they make up for in efficacy. But Matilda’s powers are depleted in the process of writing them. She emerges from the ordeal as little more than an exemplary student, a teacher’s pet. The spark behind her eyes has been extinguished, the sensitive circuit that connects mind to hand broken. Her rote memorization of facts at the end—“‘Did you know,’ Matilda said suddenly, ‘that the heart of a mouse beats at the rate of six hundred and fifty times a minute?’”—recalls the clever parrot she shoved up the chimney earlier in the book. It would make little sense to ask, at the end, “What will she do?” One fears she will go to Oxford or Cambridge to read English.

The descent from the pastoral magic of literature to its institutional legitimation at the book’s end is a hard pill to swallow—as difficult, for me at least, as it was to learn the story of Matilda’s creation. For Dennison, Matilda testifies to the growing success of Dahl’s creative partnerships in old age, above all his marriage to Liccy. On this point, he quotes with approval an obituary written by Dahl’s daughter Tessa: “She fed him with such affection and cared for him with so much devotion that his heart sang; it is she we must give thanks to for Matilda.” Treglown, by contrast, makes it clear that the published version of Matilda owes a great deal more to the interventions of Dahl’s editor, Stephen Roxburgh, than it does to his romantic awakening. The Matilda of Dahl’s first draft was “born wicked” and most likely based on Hilaire Belloc’s poem “Matilda”: “Matilda told such Dreadful Lies,/It made one Gasp and stretch one’s Eyes.” This Matilda tortured her kind parents, declared war on her cross-dressing, mustachioed headmistress, and used her powers not to read but to fix a horse race so that her favorite teacher, Miss Hayes, a compulsive gambler, could pay off her debts.

Roxburgh gave Dahl everything that makes Matilda appealing: Matilda’s unassuming intelligence, the horrendous Wormwoods, the dovelike Miss Honey. He shaped Dahl’s lazy nonsense into a story, with a beginning, middle, and end. Those of us who gained both our early, envious love of literature and a sense of its cultural imperilment from Matilda must offer thanks to Roxburgh. Certainly, Dahl did not. When he realized that Matilda was not officially under contract, he refused to do further edits and demanded a greater share of the royalties than Blake. Roxburgh agreed, but he hinted that the terms for Dahl’s future books would be less favorable given the amount of editorial labor required. Furious, Dahl withdrew his book and dismissed Roxburgh as his editor and his authorized biographer. The letter he wrote explaining his decision claimed, falsely, that Roxburgh was no longer capable of the “super-editing” he had once undertaken.

Two years away from death, Dahl could not conceive of a world beyond malice and trickery, could not hazard fighting injustice, real or imaginary, with anything other than brute force. All the golden tickets in the world were not enough to save him from the limits of his own imagination. He was doomed to live with himself, nursing his childhood hurt, his raw prejudices, his eternally wounded pride. For that, he deserves as much of our sympathy as any person, big or small, who has stumbled over his own two feet while walking the earth. In this sense, and in this sense alone, his extraordinary life was a perfectly ordinary, perfectly grown-up tragedy.

This Issue

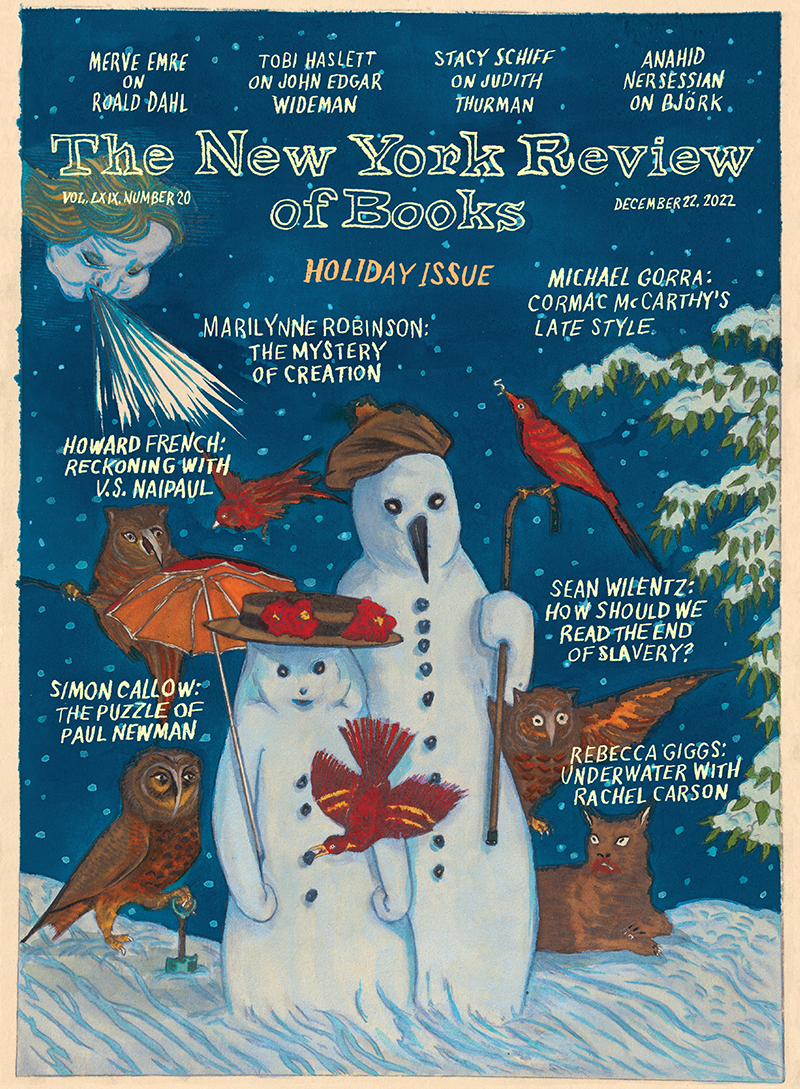

December 22, 2022

Naipaul’s Unreal Africa

A Theology of the Present Moment

-

*

For more on Blake’s illustrations, see Jenny Uglow’s richly detailed The Quentin Blake Book (Thames and Hudson, 2022). ↩