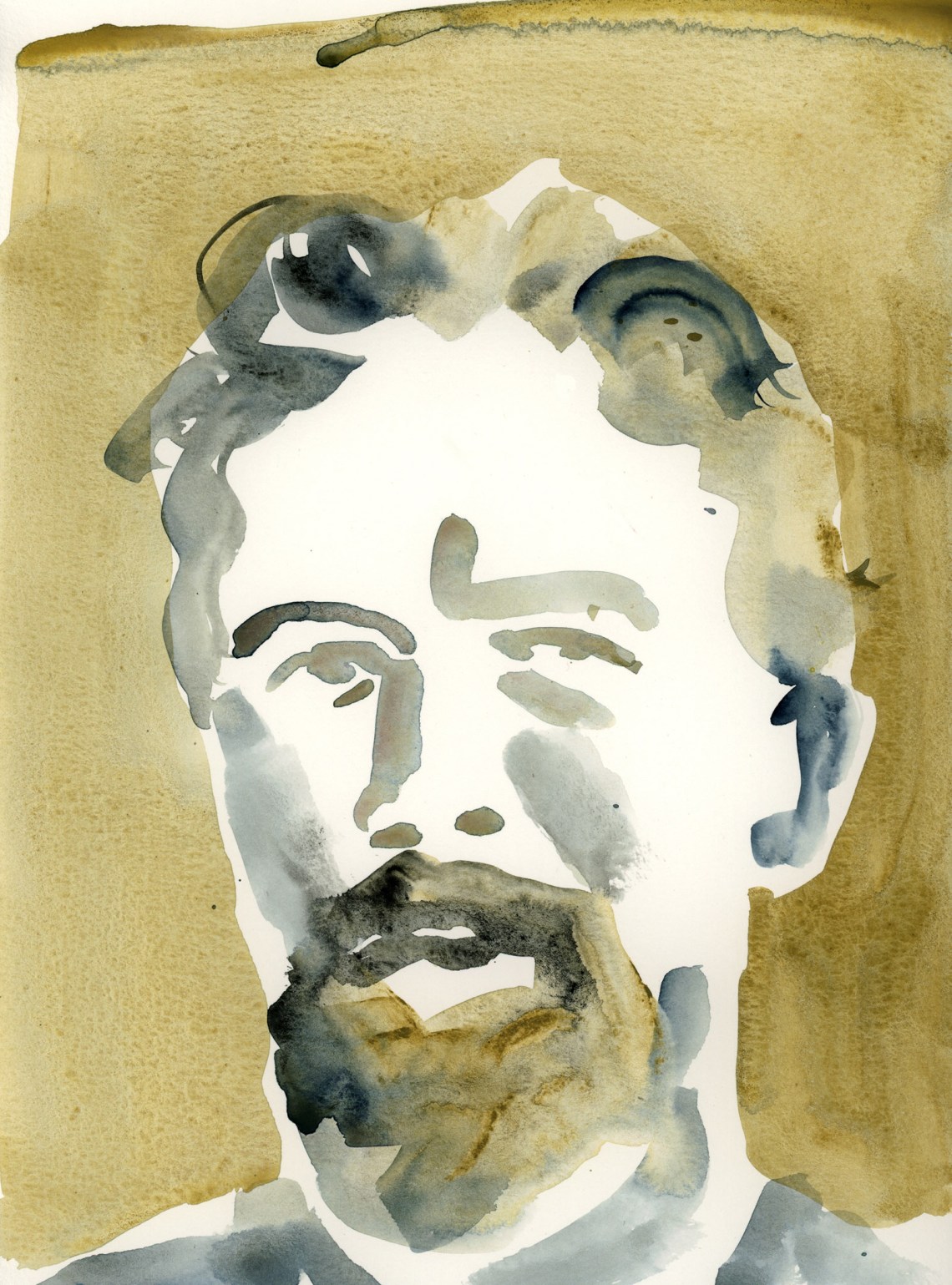

What makes Chekhov stories so wonderful? When did the humorous anecdotes he wrote for money become great art? And at what point did Chekhov appreciate his talent? Bob Blaisdell’s new book, Chekhov Becomes Chekhov, focuses on the years when it became evident, first to others and then to Chekhov himself, that a literary genius had emerged.

How straightforward Chekhov stories seem, and yet how strangely moving. Like the soul as he understood it, they appear simple but are profoundly mysterious. In her splendid book Reading Chekhov (2001), Janet Malcolm stresses how, for him, each person’s soul harbors a secret accessible to no one else. She quotes the passage in his best-known story, “The Lady with the Dog,” in which the hero, Gurov, pondering the secret love affair that constitutes his real life, imagines that one person never understands another because it is always what cannot be seen that truly matters. Everyone, he reflects, has

his real, most interesting life under the cover of secrecy…. All personal life rested on secrecy, and possibly it was partly on that account that civilized man was so nervously anxious that personal privacy should be respected.

Explaining to one correspondent that he had “autobiographophobia,” Chekhov did everything to conceal his deepest self. When in his voluminous letters he must speak of himself, Chekhov either offers trivia or conveys serious information as if he were joking. He was deliberately hard to pin down. When a journal editor, V.A. Tikhonov, requested his biography, Chekhov recited a list of obvious facts in a joking tone:

In 1890 I made a trip to Sakhalin across Siberia…. In 1891 I toured Europe, where I drank splendid wine and ate oysters. In 1892 I strolled with V.A. Tikhonov at [the writer Shcheglov’s] name-day party…. I have been translated into all languages with the exception of the foreign ones…. I am a bachelor. I would like a pension.

Even when Chekhov characters wish to reveal their deepest secret, they usually find it cannot be put into words. The hero of “The Kiss” tries to tell his fellow officers about the chance event that changed his life but cannot convey what made it so transformative:

He began describing very minutely the incident of the kiss, and a moment later relapsed into silence…. In the course of that moment he had told everything, and it surprised him dreadfully to find how short a time it took him to tell it. He had imagined that he could have been telling the story of the kiss till next morning.

No one understands, and the hero vows “never to confide again.”

More often than not, people cannot or do not listen. In The Cherry Orchard, Dunyasha cannot wait to tell Anya, who has just returned from abroad, that she has received a proposal:

Dunyasha: I’ve waited so long for you, my joy, my precious…I must tell you at once, I can’t wait another minute…

Anya (listlessly): What now?

Dunyasha: The clerk, Yepikhodov, proposed to me just after Easter.

Anya: You always talk about the same thing…. (Straightening her hair) I’ve lost all my hairpins….

Dunyasha: I really don’t know what to think. He loves me—he loves me so!

Anya (looking through the door into her room, tenderly): My room, my windows…. I am home!

Chekhov’s plays are filled with nonconversations like this and so at first glance seem entirely undramatic—Blaisdell even refers to “those comparatively dull plays”—but in fact they are rich in drama lying just beneath the surface. “Let the things that happen on stage be just as complex and yet just as simple as they are in life,” Chekhov explained. “For instance, people are having a meal at table, just having a meal, but at the same time…their lives are being smashed up.”

In one of Chekhov’s early stories, a grieving cabman tries to tell his fares about his son’s death, but no one pays attention. At last, he confides in his horse:

“Now, suppose you had a little colt…and all at once that same little colt went and died…. You’d be sorry, wouldn’t you?…” The little mare munches, listens, and breathes on her master’s hands. Iona is carried away and tells her all about it.

The title of this story is usually translated as “Misery” or “Anguish” because the Russian title, “Toska,” has no English equivalent. It suggests—as well as sorrow, dreariness, and loneliness—a sense of longing. Made into a verb, it means to miss someone. Toska may, indeed, be the defining emotion of Chekhov’s stories. Perhaps no one ever conveyed longing and loneliness so well.

In Chekhov’s longest story, “The Steppe,” about a journey across Russia’s endless, almost desolate plain, nature itself appears to suffer from toska: “The sky, which seems deep and transcendent in the steppes, where there are no woods or high hills, seemed now endless, petrified with dreariness.” The travelers discern in the distance a solitary poplar planted “God only knows why”:

Advertisement

Was that lovely creature happy? Sultry heat in summer, in winter frost and snowstorms, terrible nights in autumn when nothing is to be seen but darkness and nothing is to be heard but the senseless angry howling of the wind, and worst of all, alone, alone for the whole of life.

A peculiar beauty dwells in such sadness, when

you are conscious of yearning and grief, as though the steppe knew she was solitary, knew that her wealth and her inspiration were wasted for the world, not glorified in song, not wanted by anyone; and through the joyful clamour one hears her mournful, hopeless call for singers, singers!

Chekhov’s story is that longed-for song.

Chekhov’s life and art, Malcolm writes, were “a kind of exercise in withholding.” Even with the Soviet censor’s prudish cuts restored, his letters fail to disclose “anything essential about him…. Chekhov’s privacy is safe from the biographer’s attempts upon it.” Malcolm exaggerates, of course, and the best biographies offer hints to Chekhov’s inner life, revealed in part by the very ways he tried to conceal it. Malcolm’s opposite, Blaisdell—a professor of English at CUNY—confidently reveals what he supposes the author concealed. To do so, he weaves from stories, letters, and recollections a narrative of Chekhov’s life in 1886 and 1887, when he emerged as a great writer and became, to his own amazement, celebrated. It is not so much Chekhov’s evolution as an artist that concerns Blaisdell as the recognition, by Chekhov himself and others, that his works are indeed masterpieces.

Blaisdell conveys how busy these years were. The main support of his parents and siblings, Chekhov, a young doctor, managed to produce 112 short stories, articles, and pieces of humor writing in 1886 and another 66 in 1887. He also wrote long letters, some of which are themselves literary gems appearing in anthologies of Russian writing.

One letter Chekhov received in March 1886 changed his view of himself. The veteran writer Dmitry Grigorovich offered his unsolicited opinion that Chekhov was a major literary talent and urged him to take his work more seriously. Chekhov, Grigorovich asserted, should not write so hurriedly and instead make each story the work of genius it could be. “I am convinced…you will be guilty of a great moral sin if you do not live up to these hopes,” he enthused. “All that is needed is esteem for the talent which so rarely falls to one’s lot.”

Blaisdell for some reason finds this letter insufferably condescending. “Hmph!” he snorts. “Grigorovich sounds like another one of Chekhov’s comic windbags.” Chekhov’s reaction was quite different: “Your letter…struck me like a flash of lightning. I almost burst into tears, and now I feel it has left a deep trace in my soul!” Then he added that a letter from a writer so well known “is better than any diploma.” Chekhov, the man of brevity and understatement, went on and on in this awed tone. He was clearly deeply moved. Admitting the justice of Grigorovich’s criticisms, Chekhov closed by asking for his photograph. From this point on, Chekhov really did begin to devote greater care to his fiction.

Blaisdell admires the classic 1962 biography by Ernest Simmons, who offers no theories or interpretations. Instead, he quotes generously, with an eye to what is most interesting, from letters, memoirs, and stories, so readers can form their own impressions. Like Simmons, Blaisdell cites at length the most famous letters and, month by month, quotes from Chekhov’s best-known stories. Unlike Simmons, Blaisdell offers many interpretations. And unlike Chekhov, who always advised concealing one’s subjectivity, Blaisdell displays his own personality all too frequently. But readers can usually overlook such displays and immerse themselves in the delicious texts he strings together.

The book’s flyleaf and introduction promise to follow Chekhov’s becoming “engaged and unengaged” with Evdokiya (Dunya) Efros, a Jewish friend of Chekhov’s sister Maria, but, as Blaisdell knows, it is far from clear any engagement existed. In the midst of a long letter he wrote to his friend Bilibin, who was himself engaged, Chekhov drops in passing, “Last night, bringing a young lady home, I made her a proposal. I went out of the frying pan and into the fire… Bless my marriage.” In another letter to Bilibin he wrote:

Thank your fiancée for remembering me and tell her that my wedding will most likely—alas and alack! The censor has cut out the rest…. My one and only is Jewish…. She has a terrible temper. There is no doubt whatsoever that I will divorce her a year or two after the wedding.

Four weeks later Chekhov wrote to Bilibin, “With my fiancée, I broke off completely. That is, she broke off with me. But I still didn’t even buy a revolver.”

Advertisement

As Blaisdell notes, when Chekhov had news,

he passed it along matter-of-factly to his brother Alexander or [his publisher and friend] Leykin, but…neither confidant was aware of this engagement. Alexander was never one to hold back, and his letters contain no querying about Chekhov’s relationship with Efros.

If an engagement actually existed, “why did Chekhov only talk about [it] to Bilibin?” Maria, though Dunya’s close friend, claimed she never even heard of any such engagement until decades later. “If Efros took the proposal seriously and told anybody about it, no one accounted for her ever having done so,” Blaisdell observes. Little wonder the biographer Ronald Hingley concluded that there was no engagement.

Blaisdell suggests another possibility:

I, on the other hand, think that there was an engagement, but that it started out as a joke. That is, at the conclusion of his wild name day party, Chekhov proposed and Efros accepted…as a joke. And they played along at this together until they didn’t know themselves whether it was a joke or not.

This seems possible. Of course, other possibilities also come to mind: for example, that the joke was between Chekhov and Bilibin rather than Chekhov and Efros. Perhaps Chekhov had a short infatuation with Efros that he knew wouldn’t be reciprocated, or was joking about her having no suitors, or was mocking his own inability to make commitments in love.

The problem is that Blaisdell repeatedly refers to the engagement as a simple fact, and then interprets stories accordingly. “In the winter of 1886,” he declares in the book’s introduction, Chekhov

became engaged and unengaged to be married…. When he was in the midst of his frustrating and anxious engagement, young couples in his stories are continually making their rancorous way into or out of their relationships.

Commenting on “A Serious Step,” about a father’s reaction to his daughter’s engagement, Blaisdell presumes that Chekhov was pondering his own. He reconstructs Chekhov’s thoughts about being engaged:

It seems that every time Chekhov contemplated marriage this year, he found reasons not to proceed. But why not go ahead and take that “serious step”? Dunya Efros, however, seems to have had enough for now of his waffling.

Blaisdell gives us no evidence for her supposed impatience.

Blaisdell loves any prurient hint. When Chekhov, teasing Bilibin for his “softness,” mentions rough lovemaking, Blaisdell asks whether we can suppose that Chekhov and Efros “had gone at it in a rough manner? We can wish Chekhov was as enlightened as we are in 2022 and that he would watch his language and behavior.” Has Blaisdell forgotten that the engagement may not have existed, or that, if it did, it remained at most something between joke and reality?

When in Nice an editor asked Chekhov to write a story based on his travel impressions, Chekhov declined, saying that “I am able to write only from memory, I never write directly from observed life”—but Blaisdell usually insists on a close, direct connection between stories and the immediate circumstances in which they were written. “Anton Chekhov’s biography in 1886–1887 is captured almost completely in the writing that he was doing,” Blaisdell’s book begins. “Reading the stories, we are as close as we can be to being in his company.” The 178 pieces Chekhov wrote in these years, read “in conjunction with the personal letters to and from him…become a diary of the psychological and emotional states of this conspicuously reserved man.” By this method, Blaisdell claims to get behind Chekhov’s curtain of reserve.

Blaisdell allows that Chekhov sometimes concealed connections between his life and stories by switching genders or altering circumstances, but he confidently pierces such concealments. Of course, everything in writers’ work must have some basis in their experience, but why must the connection be direct or immediate? If Blaisdell phrased his guesses as simply intriguing possibilities, they would be more, not less, persuasive, because as it is they provoke a skeptical response. He reads Chekhov’s story “Mire,” with its seductive Jewish heroine, Susanna, as an expression of resentment toward his Jewish fiancée. He resolved his “marriage problem,” Blaisdell observes, “the way, perhaps, a fourteen-year-old boy would, by blaming and ridiculing an innocent person who had just been minding her own business.” So strong was the need to ridicule Efros that, although “no one who knew him ever accused him of being anti-Semitic,” he indulged in anti-Semitism by creating this unappealing Jewish character. “Chekhov has confusing or confused motives,” Blaisdell concludes. “One is to describe a literary type, a newfangled Circe, another is falling under the spell of Dunya Efros. Our author’s misogynistic and anti-Semitic vision results in Susanna.” It is a comment that says little about Chekhov while again displaying how “enlightened…we are in 2022.”

So apparently simple are Chekhov’s stories in Blaisdell’s account that it is hard to identify what makes them masterpieces. Like poems, they suggest much more than is stated directly. Chekhov loved to give stories an unexpected turn. Just before they end, we often get a new viewpoint or learn an important fact allowing us to see events forming a second story, much deeper than the first. If one misses the turn, one does not discern what makes a good story a great one.

Consider “Enemies,” which opens just after the district doctor Kirilov’s six-year-old son has died of diphtheria. Russian doctors at this time had little prestige, and Kirilov is evidently poor and unattractive. Chekhov describes grief as no one else could. The wealthy Abogin arrives to summon the doctor to his dying wife’s bedside. Kirilov can barely grasp what Abogin is saying and, unconscious of what he is doing, leaves the room to observe his dead son and grief-stricken wife (though Abogin mistakenly assumes he is getting his things for the journey):

That repellent horror which is thought of when we speak of death was absent from the room. In the numbness of everything, in the mother’s attitude, in the indifference on the doctor’s face there was something that attracted and touched the heart, that subtle, almost elusive beauty of human sorrow which men will not for a long time learn to understand and describe.

That “elusive beauty” is Chekhov’s trademark. Who else would describe the face of a deeply grieving person as expressing “indifference”? Kirilov’s pain surpasses sobbing and can be handled only by numbing and distancing himself from reality. As Kirilov goes from room to room,

he raised his right foot higher than was necessary, and felt for the doorposts with his hands, and as he did so there was an air of perplexity about his whole figure as though he were in somebody else’s house, or were drunk for the first time.

So abstracted is he that when he returns, he can hardly recall why Abogin is there. At last he explains that his son has died and he cannot leave his wife. Using the flowery, educated language he is used to, Abogin appeals to the doctor’s conscience, sense of duty, and legal obligation to go care for his own wife. Kirilov is especially annoyed by Abogin’s invoking “the love of humanity,” an ideal common among wealthy and well-educated people but foreign to the doctor, who experiences it as the less fortunate often experience the unintentionally condescending language of their “betters”: “‘Humanity—that cuts both ways,’ Kirilov said irritably.” Finally he agrees to go.

When they arrive at Abogin’s house, the two men observe each other. The doctor was “stooped,…untidily dressed and not good-looking.” His appearance and “uncouth manners” suggest “years of poverty, of ill fortune, of weariness with life and with men.” Abogin’s appearance could not differ more. A tall, sturdy man with “large, soft features,” Abogin “was elegantly dressed in the very latest fashion…and there was a shade of refined almost feminine elegance” in his gestures. In Abogin’s luxurious drawing room, the doctor “scrutinized his [own] hands, which were burnt with carbolic,” and notices “the violoncello case,” testifying to Abogin’s cultural superiority.

It turns out that Abogin’s wife has only faked illness so she could run off with her lover. Abogin despairs at the loss. Interestingly, he is also insulted at the way his wife has left him. “If she did not love me,” he asks, “why did she not say so openly, honestly, especially as she knows my views on the subject?” What views? As any reader would have known, it had long been a commonplace among intellectuals that when a wife fell in love with another man, a proper, enlightened husband would bless their union. By leaving secretly, Abogin’s wife has demonstrated doubt of his enlightenment.

The doctor flies into a rage at this display of upper-class values:

Go on squeezing money out of the poor in your gentlemanly way. Make a display of humane ideas, play (the doctor looked sideways at the violoncello case) play the bassoon and the trombone, grow as fat as capons, but don’t dare to insult personal dignity!

At first amazed, Abogin responds in kind, and the two hurl “undeserved insults” at each other:

I believe that never in their lives, even in delirium, had they uttered so much that was unjust, cruel, and absurd. The egoism of the unhappy was conspicuous in both. The unhappy are egoistic, spiteful, unjust, cruel, and less capable of understanding each other than fools. Unhappiness does not bring people together but draws them apart, and even where one would fancy people should be united by the similarity of their sorrow, far more injustice and cruelty is generated than in comparatively placid surroundings.

Waste is one of Chekhov’s great themes, and what is wasted here is the opportunity for empathy. As if to demonstrate what Abogin and Kirilov miss, he makes us empathize with each character’s failure of empathy.

The story might have ended here, but a surprise is in store. On the journey back, “the doctor thought not of his wife, nor of his [son] Andrey,” but of privileged people like Abogin. With thoughts “unjust and inhumanly cruel,” Kirilov

condemned Abogin and his wife and…all who lived in rosy, subdued light among sweet perfumes, and all the way home he despised them till his head ached. And a firm conviction concerning those people took shape in his mind.

The story turns out to be about not just the failure of empathy but also the way political “conviction,” in this case based on class hatred, arises. The last sentence is the most horrible: “Time…will pass, but that conviction, unjust and unworthy of the human heart, will not pass, but will remain in the doctor’s mind to the grave.” That is, the class hatred he now indulges will prove more long-lasting, and sink deeper into his soul, than even his grief over the loss of his son. As we reread the story, we can see how Chekhov has prepared for this ending, but it surprises nonetheless. A great story has become still greater.

Devoting fifteen pages to “Enemies,” Blaisdell focuses, as we have come to expect, on the possible resemblance between doctor Kirilov and Chekhov, another doctor who was also “often run down and exhausted,” suffering from minor and serious complaints, and, perhaps, moved by “someone’s shaky voice” to go when he had resolved not to. And “the anger, the fury, the disgusting hatred the enemies fling at each other—had Chekhov felt or only witnessed it?” Blaisdell grasps that the heroes of “Enemies” could have appreciated each other’s sorrow, but he misses the significance of Abogin’s high-minded appeals and does not detect the insult he senses in how his wife has left him. The second story about the origin of convictions utterly escapes him, and so the ending disappoints him: “Chekhov had multiple opportunities to revise this story. He did not. He tacked on the moral and left it there, forever.”

Something similar happens with Blaisdell’s discussion of “On the Road,” in which a man, Likharev, and a woman, Ilovaisky, are trapped in an inn during a Christmas Eve storm. Likharev recounts his life of total commitment to one ideology after another, a life he describes as typically Russian. “This faculty is present in Russians in its highest degree,” he comments.

Russian life presents us with an uninterrupted succession of convictions and aspirations, and if you care to know, it has not yet the faintest notion of lack of faith or scepticism. If a Russian [intellectual] does not believe in God, it means he believes in something else.

Likharev has never experienced either disillusionment or skepticism because whenever he abandoned one belief system, he immediately adopted another. At first fanatically devoted to “science,” Likharev abandoned it for nihilism and then for populism: “I loved the Russian people with poignant intensity; I loved their God and believed in Him.”

Likharev’s enthusiasm is infectious, especially to women, and as the story draws to a close Ilovaisky is ready to follow him anywhere, but he does not ask her to. The succession of ideologies does not interest Blaisdell, who focuses on Ilovaisky’s attraction to the hero’s sheer vitality. He is therefore puzzled that, on Christmas morning, Likharev and Ilovaisky listen with pleasure to a crowd singing a popular ditty:

Hi, you Little Russian lad,

Bring your sharp knife,

We will kill the Jew, we will kill him,

The son of tribulation…

Why did Chekhov include these terrible verses? Of course, Russian peasants were anti-Semitic, Blaisdell allows, but their song might easily have been omitted, especially because the story happened to appear in the “right-wing anti-Semitic newspaper” of Chekhov’s friend Suvorin.

Again, Blaisdell misses the turn. The fact that these verses are appalling is the whole point. Likharev enjoys them, “looking feelingly at the singers and tapping his feet in time,” because of his populist sympathies. However appealing and inspiring, ideology, to which the Russian intelligentsia was so susceptible, can lead to horror. In 1881 the populist People’s Will assassinated Tsar Alexander II, and Russia witnessed murderous pogroms, perhaps provoked by the fact that a Jewish woman had played a prominent part in the plot. The People’s Will cynically decided to exploit anti-Jewish sentiment to unleash popular rebellion. Two decades later it was the government that inspired pogroms, but in the early 1880s it was populist revolutionaries. On August 30, 1881, the Executive Committee of the People’s Will issued a manifesto, written in Ukrainian and addressed to “good people and all honest folk in the Ukraine.” It began:

It is from the Jews that the Ukrainian folk suffer most of all. Who has gobbled up all the lands and forests? Who runs every tavern? Jews!… Whatever you do, wherever you turn, you run into the Jew. It is he who bosses and cheats you, he who drinks the peasant’s blood.

As Chekhov writes the story, readers, like the heroine, first sense the attractiveness of Likharev and his enthusiasms. But the story turns and, without explicitly saying so, exposes the horror that Likharev’s charismatic idealism may entail. I am not sure whether Blaisdell’s ignorance of Russian culture—his academic training was in English literature and he learned to read Russian in middle age—accounts for his missing this turn, or whether, as in “Enemies,” it is his lack of interest in ideological movements.

Yet in the end these shortcomings do not matter that much. Blaisdell may miss the turn in Chekhov’s stories, but he captures the turn in Chekhov’s life. The real story Blaisdell tells is Chekhov’s gradual realization that his tales are not just funny anecdotes that pay the bills but great literature. As he explained to Grigorovich, “I have hundreds of friends in Moscow, and among them a dozen or two writers, but I cannot recall a single one who reads me or considers me an artist.” He could not alter his rushed writing immediately, he admitted to Grigorovich, but bit by bit he did so. Blaisdell’s entertaining book traces this change in Chekhov’s self-perception and allows us to trace the emergence of a literary genius.

This Issue

April 6, 2023

Becoming Enid Coleslaw

Putin’s Folly

Descriptions of a Struggle