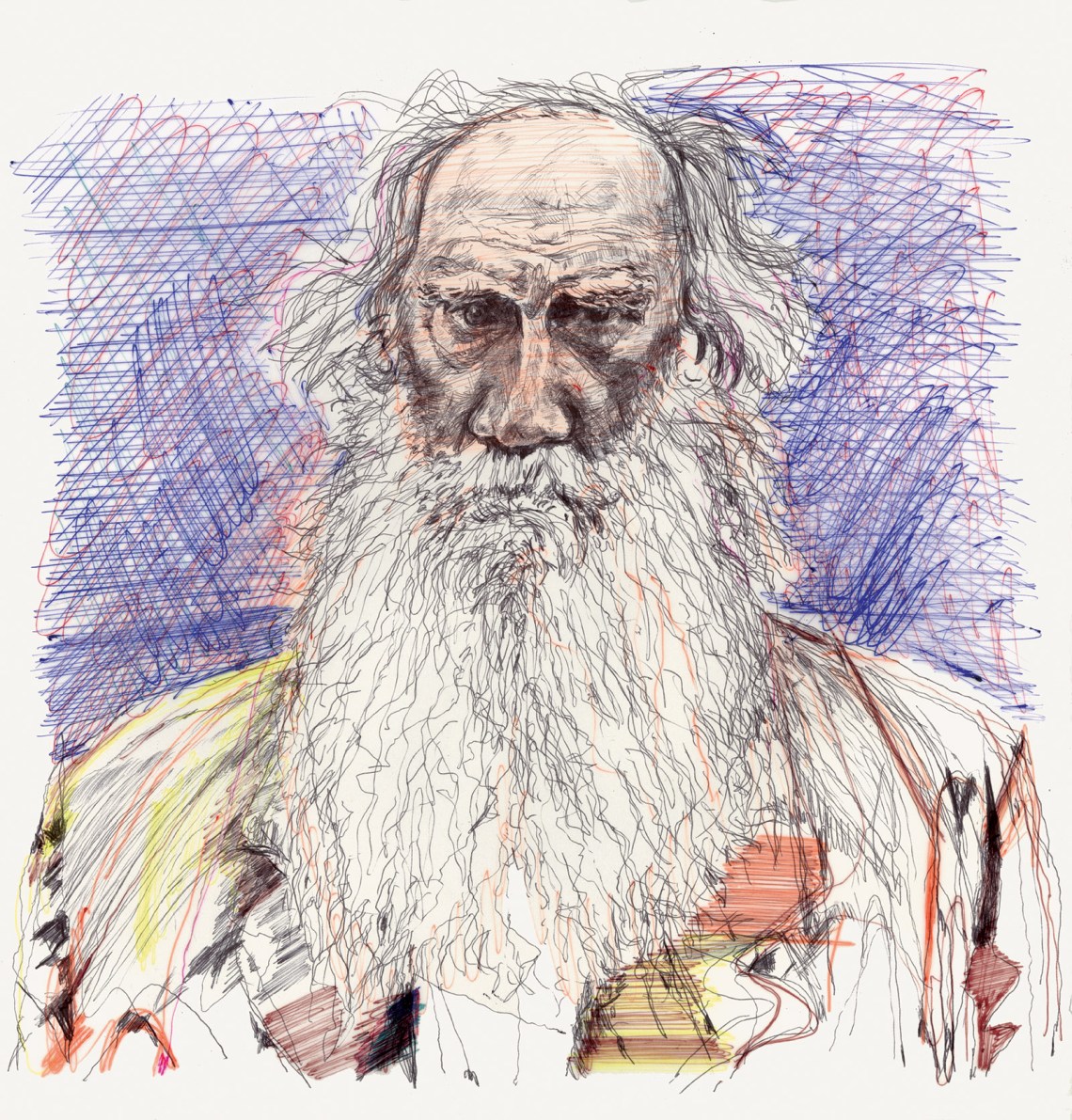

Tolstoy’s contemporaries called him the poet of death, and no one has ever described dying so well. “If a man has learned to think,” Maxim Gorky reports him saying, “no matter what he may think about, he is always thinking of his own death…. And what truths can there be, if there is death?”

People hide from death. They usually act as if dying happens to others, but not to themselves. But sooner or later each of us must face the fact that it is not some abstract person who is dying but I, myself. When this happens to the eponymous hero of The Death of Ivan Ilych (1886), he is so unaccustomed to the thought of his own death that “he simply did not and could not grasp it”:

The syllogism he had learned from Kiesewetter’s Logic: “Caius is a man, men are mortal, therefore Caius will die,” had always seemed to him correct as applied to Caius, but certainly not as applied to himself. That Caius—man in the abstract—was mortal, was perfectly correct, but he was not Caius, not an abstract man, but a creature quite, quite separate from all others…. What did Caius know of the smell of that striped leather ball he had been so fond of? Had Caius kissed his mother’s hand like that, and did her dress rustle so for Caius?…

Caius really was mortal, and it was right for him to die; but for me, little Vanya, Ivan Ilych…it’s altogether a different matter.” …Such was his feeling.

All civilized life, Ivan Ilych realizes, consists of “curtains” designed to shield us from our own mortality. When Ivan Ilych is dying, he finds himself absolutely alone, lonelier than he would be in a remote desert. No one can appreciate what he is going through, and that incomprehension magnifies the horror.

Long before writing The Death of Ivan Ilych, Tolstoy had explored the absolute separateness of the dying person. The death of Prince Andrei, one of the heroes of War and Peace (1869), extends over a hundred pages and has been viewed by many as the greatest death in world literature. What particularly impressed Tolstoy’s contemporaries was his seemingly superhuman ability to trace Prince Andrei’s thoughts after he loses the ability to communicate with others. “How does Count Tolstoy know [all] this?” asked the novelist Konstantin Leontiev. “He did not rise from the dead and visit us after his resurrection.” And yet he convinces readers that, yes, it could really be just this way.

After being wounded in battle, Prince Andrei experiences “an alienation from all things earthly.” He comes to feel that he pities, even loves, the suffering man near him having his leg amputated. Only then does he realize that the man he has loved is his worst enemy, Anatol Kuragin, who nearly abducted his fiancée, Natasha. Rather than regret his pity, Andrei embraces it:

Compassion, love for our brothers, for those who love us and for those who hate us, love for our enemies—yes, that is the love which God preached on earth…that is what remained for me had I lived. But now it is too late. I know it!

Even Dostoevsky, with all his insight into the mind, could not make Christian love psychologically convincing. Only Tolstoy ever did, and he did it twice, once in War and Peace and again in Anna Karenina (1878). It transforms the last person we would expect, the emotionally stilted Alexei Karenin. Tolstoy traces dozens of tiny changes in Karenin’s consciousness and feeling that lead him to forgive and love the unfaithful wife he has hated. Since each change is plausible, we grant the surprising conclusion to which they lead.

In both novels, Tolstoy, after accomplishing the seemingly impossible, surprises us again by showing that Christian love may not be desirable. When Andrei finds himself cared for by Natasha, he realizes that such love is possible only if one loves everyone equally. It places one beyond desire and the flow of time, and so precludes “earthly love” for a particular person. From this point on, earthly love and Christian love, the desire to live and the divine indifference incompatible with life, compete in Andrei’s soul. At last Christian love triumphs, and he begins to live almost posthumously.

Natasha and Marya, Andrei’s sister, recognize that he has ceased to understand the simplest things about human concerns because he has grasped something incomprehensible to the living. They exist in time, with goals and fears, but he experiences a permanent present. That is how he interprets these lines from the Gospel: “Behold the fowls of the air: for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns…. Take therefore no thought for the morrow.” He wants to quote these words to Natasha and Marya but thinks:

Advertisement

“No, they would interpret it in their own way, they don’t understand that all these feelings they set such store by—all our feelings, all those ideas that seem so important to us, do not matter. We cannot understand each other,” and he remained silent.

Truly to understand life is to regard it from beyond time, but then one cannot live.

Forever obsessed with death, Tolstoy experienced in the late 1870s a psychological crisis that paralyzed him, which he describes in the autobiographical essay Confession (1882) in almost identical terms as he did Levin’s existential terror in the last part of Anna Karenina. Levin, the novel’s hero, endures “fearful moments of horror.” Work, achievement, any human purpose: all seem utterly pointless since death annihilates everything. Even one’s descendants—and the whole human race, for that matter—will disappear in an instant compared to eternity. With that characteristic Russian dissatisfaction with practical compromise, Levin insists that if meaning is vulnerable to time and change, a truly thinking person like himself cannot consent to continue living: “Without knowing what I am and why I am here, life’s impossible; and that I can’t know, so I can’t live.”

Educated in the sciences, Levin previously placed his faith in his materialistic “new convictions” but now finds that science not only does not answer but cannot even address the questions concerning him: “He was in the position of a man seeking food in a toy shop or at a gunsmith’s.” The nonmaterialist philosophers, he discovers, offer clever arguments “to refute other theories,” but this is ultimately just useless ratiocination. He decides that all thought, existing and to come, only demonstrates the following truth: “In infinite time, in infinite matter, in infinite space, is formed a bubble-organism, and that bubble lasts a while and bursts, and that bubble is I.”

“It had come to this,” Tolstoy writes in the Confession.

I, a healthy, fortunate man, felt that I could no longer live…. I cannot say that I wished to kill myself. The power which drew me away from life was stronger, fuller, and more widespread than any mere wish. It was a force similar to the former striving to live, only in a contrary direction.

If he did not kill himself, Tolstoy explains, it was only to make sure he had not overlooked anything:

And it was then that I, a man favored by fortune, hid a cord from myself lest I should hang myself from the crosspiece of the partition in my room where I undressed alone every evening, and I ceased to go out shooting with a gun lest I should be tempted by so easy a way of ending my life.

Tolstoy began to escape this cycle of thoughts only when he extended his gaze beyond educated, wealthy people to those who live quite differently. Could his despair have resulted from his way of life? Ivan Ilych also begins to find meaning only when he recognizes that he has lived wrongly, a possibility that at first seems absurd to him:

“Maybe I did not live as I ought to have done,” it suddenly occurred to him…. [He] immediately dismissed from his mind this, the sole solution to all the riddles of life and death, as something quite impossible.

(Only Tolstoy, I imagine, could get away with claiming there’s a “sole solution to all the riddles of life and death”—and that he knows it.)

Tolstoy came to realize that “I and a few hundred similar people” living an unnatural, privileged life “are not the whole of mankind,” as he had assumed, while regarding “those milliards of others…[as] cattle of some sort—not real people.” Peasants evidently do find meaning in life and accept “illness and sorrow…with a quiet conviction that all is good.” These people professed belief in Orthodox Christianity, and so Tolstoy tried to return to the faith of his upbringing, but its focus on what he viewed as empty ritual and absurd theology appalled him. To accept the church’s faith, he would have to surrender his reason. Could it be that the peasants actually understood something else that they could not articulate—that what they meant by “God” was not the church’s God?

Ludwig Wittgenstein, who was deeply influenced by Tolstoy, recognized that faith entails not some doctrine or fact about the world but a different sense of the world as a whole: “It becomes an altogether different world. It must, so to speak, wax and wane as a whole. The world of the happy man is a different one from that of the unhappy man.” This is the conclusion that Levin reaches at the end of Anna Karenina, and if Tolstoy had stopped there, he would have found a faith consonant with the insights of his major literary works.

Advertisement

Alas, Tolstoy went much further, to the point where he rejected War and Peace, Anna Karenina, and most of Europe’s literary and artistic masterpieces. What changed was his very style of thinking. In his famous essay on Tolstoy, “The Hedgehog and the Fox,” Isaiah Berlin—meditating on Archilochus’s gnomic line “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing”—envisaged two types of thinker. Hedgehogs, like Hegel, build systems offering “a single, universal organizing principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance.” By contrast, foxes, like Shakespeare, recognize the variety of experiences that do not form a whole and demand a multitude of perspectives. Berlin recognized both impulses in Tolstoy, who grasped for systems only to shatter them with his relentless skepticism.

It is conventional to speak of two Tolstoys, before his conversion (around 1880) and after, and we may say, with some qualification, that in his two great novels the fox predominates, while after the conversion the hedgehog usually reigns supreme. War and Peace demolishes all systems, wherever they occur. Pierre, the novel’s other hero, begins with the utopian hope of discovering a great truth on which everyone can agree. Convinced that the answer lies in his view of Freemasonry, he is distressed that even those who agree with him do so “with stipulations and modifications he could not agree to,” since what he wanted was absolute coincidence of views. “At this meeting,” Tolstoy explains, “Pierre for the first time was struck by the endless variety of men’s minds, which prevents a truth from ever appearing exactly the same to any two persons.” A thousand pages later, Pierre achieves Tolstoyan wisdom when he accepts this inescapable variety, acknowledging

the possibility of every person thinking, feeling, and seeing things in his own way. This legitimate individuality of every person’s views, which formerly troubled or irritated Pierre, now became the basis of the sympathy he felt for other people and the interest he took in them.

After 1880 Tolstoy argued like Pierre at his most naive moments. He insists that the truth is absolutely clear and indubitable. The very demand for proof is misguided: “Just as it is impossible to shine a light onto light itself, it is impossible to prove the truthfulness of truth…. Truth proves everything else.” The same fundamental insight, he decided, lies at the heart of all religions and was enunciated with special clarity by Jesus, but everywhere the clerisy has perverted it. The Gospel text as we have it has been hopelessly corrupted, Tolstoy decided, and so he learned Greek and composed what he deemed the true Gospel, which, he insisted, has only one possible meaning. In an article included in Inessa Medzhibovskaya’s collection Tolstoy as Philosopher, Tolstoy maintains that “to comprehend the truth of Christian teaching, one must not interpret the gospels but understand them the way they are written”—his way.

If one does, one realizes that the death we fear does not exist, as Tolstoy explains at length in On Life, a critical edition of which Medzhibovskaya released a few years ago. Death happens only to the physical body, but our “reasonable consciousness” is immaterial and cannot die. It exists outside time and space, and we are nearest to God when we live entirely in the present, taking “no thought for the morrow,” as Prince Andrei understood. In fact, as Plato realized, our soul has always existed and will always exist, although what life is like outside time we neither know nor need to know. It is enough to know that it will not be destroyed at death.

Tolstoy’s new religion attracted adherents around the world, and according to its tenets the insights reached by Prince Andrei, which War and Peace recognizes as incompatible with life, can and must be applied to life. That means loving everyone equally and giving up all preference for friends and family. “These feelings—a preference for certain creatures, for example our children,” Tolstoy reasons in On Life, “only demonstrates the energy of the animal individuality…. Preference does no good for people, or it creates an even greater evil.”

Universal love demands that one must never resist evil with violence, and so one must embrace not only pacifism but also anarchy, since laws ultimately depend on force. One must also endeavor to achieve absolute chastity, even within marriage, and so escape the sexuality that binds us to our “animal” self. In much the same way, we must forsake all private property, which ties us to our base needs and wants. High culture, which depends on the stolen labor of peasants, must be surrendered.

Of course, as Tolstoy’s wife, Sonya, who did not accept his new views, pointed out, Tolstoy failed to observe these principles, a fact of which he was well aware. Sometimes he answered such criticisms by insisting that while he was blameworthy the principles remained sound. One of his most remarkable stories of this period, “Father Sergius,” offers an evidently autobiographical meditation on the difficulties of a man striving to become a saint but constantly failing. Sergius humbles himself only to take pride in his own humility, and like his creator he engages in complex forms of self-deception.

Tolstoy never convincingly answered obvious objections to his views. What would happen if individuals never used force, if laws were abolished, and if nations left themselves open to invasion by ruthless neighbors? He replied that things are so bad they couldn’t be worse. At other times he insisted that neither evil nor evil people really exist. For Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, who chronicled the Gulag, such cavalier reasoning was appalling. At the beginning of his novel August 1914, Sanya, a Tolstoyan, visits Tolstoy to have his doubts resolved. “Are you sure, Lev Nikolaevich,” he asks,

that you don’t exaggerate the power of human love?… What if love is not so strong, not necessarily present in all men, what if love cannot prevail…. Wouldn’t that mean that your teaching…is extremely premature? If so, ought we not to envisage some intermediate stage…?

Tolstoy replies—as he actually did many times—that there can be no compromise with absolute nonresistance. Love is always the only answer. Political reforms—the rule of law, democracy, constitutions—are not only fruitless but positively harmful, because they rely on “external” changes rather than the spiritual perfecting of individuals. What’s more, “the real people—the peasantry, that is…don’t need any of these things.” To the argument that some uses of force are better than others, Tolstoy replied, “There is as much difference as between cat-shit and dog-shit.”

For Sanya, as for Solzhenitsyn himself, such thinking reflected a dangerously naive view of evil:

You say…that evil does not come from an evil nature, that people are evil not by nature but out of ignorance…. But…it isn’t at all like that, Lev Nikolaevich, it just isn’t so! Evil refuses to know the truth. Rends it with its fangs! Evil people usually know better than anyone else just what they are doing. And go on doing it. What are we to do with them?

Just explain again more patiently, Tolstoy answers.

No matter the topic, Tolstoy seemed to offer the same simple answers. Before his conversion, he acknowledged that science’s inability to address questions of meaning did not impugn scientific knowledge itself. After his conversion, Tolstoy rejected all recognized sciences—not just pseudosciences like social Darwinism or aspiring ones like sociology, but hard sciences as well. The only true science, Tolstoy maintained, is the science of Socrates, the Buddha, and Jesus—the science of how to live. All else is useless, indeed pernicious, distraction:

Our science, in order to become science and to be really useful and not harmful to humanity, must first of all renounce its experimental method…and must return to the only reasonable and fruitful conception of science…how people ought to live.

As one might expect, Tolstoy’s view of art, though often perverse, remained considerably more nuanced than his view of science. In his most developed statement on the topic, What Is Art?, he defines it much as he did before his conversion: The artist discerns an emotion with exceptional precision, and by way of a given medium enables the audience to experience the same emotion. He calls this process “infection,” which means that empathy is a necessary feature of the artistic process. When readers identify with Anna Karenina and vicariously experience her sequence of thoughts and feelings, they can identify with her in all her particularity.

Because emotions, finely enough perceived, are infinitely various, this form of empathy can teach the audience something genuinely new. Contemplating one of his paintings, the artist Mikhailov, a character in Anna Karenina, can be absolutely sure “that no one had ever painted a picture like it. He did not believe that his picture was better than all the pictures of Raphael, but he knew that what he had tried to convey in that picture no one had ever conveyed.” It follows for Tolstoy that “one of the chief conditions of artistic creation is the complete freedom of the artist from every kind of preconceived demand.”

Much of what passes for art does not enable this kind of empathy. It relies, instead, on cleverness, striking effects, or variations on other works of art. That is how Anna’s lover Vronsky paints. He “imitates” other works and adopts the methods of a particular school, but “he had no conception of the possibility of knowing nothing at all of any school of painting, and of being directly inspired by what is within the soul, without caring whether what is painted will belong to any recognized school.”

What Is Art? adds a new idea to Tolstoy’s thinking by making the criteria for evaluating art entirely different from those defining it. A better work of art is not one that infects more forcefully, but one that infects with moral emotions. Thus Maupassant’s stories are genuine works of art but bad ones, since they convey immoral erotic feelings. Good art also should also be accessible to ordinary people, to “plain men” and not just “erudite” people, that is, to “perverted and at the same time self-confident individuals.”

A particular incident led Tolstoy to try his hand at broadly accessible art very different from his earlier works. Speaking with a famous astronomer who had lectured on the spectrum analysis of the Milky Way, Tolstoy, realizing that most of the audience did not even know why day follows night, suggested that the astronomer lecture on elementary topics: “The wise astronomer smiled as he answered, ‘Yes, it would be a good thing, but it would be very difficult. To lecture on the spectral analysis of the Milky Way is far easier.’” “And so it is with art,” Tolstoy concludes. “To write a rhymed poem dealing with the times of Cleopatra…is far easier than to tell a simple story without any unnecessary details, yet so that it should transmit the feelings of the narrator” to ordinary people.

Experimenting with the difficulties of simplicity, Tolstoy produced some small masterpieces, the best of which concern his favorite theme, death. In “What People Live By,” an angel sent to fetch the soul of a dying woman, who has just given birth to twin girls, heeds her plea for life so she can care for her babies. God takes her soul anyway and punishes the angel’s disobedience by sending him to live on earth as a human until he learns what distinguishes the life of mortals from that of angels. Finding himself freezing and naked, the angel witnesses a poor shoemaker first ignore him but then turn back to rescue him. Bringing him home, the shoemaker persuades his reluctant wife, who knows they lack even bread for the morrow, to take the wayfarer in. We will all die, he says, and suddenly love enters her heart. From a rational perspective, the argument makes no sense. Precisely because she is mortal, giving scarce food to a stranger may bring her own death from hunger all the closer. But—and this is the angel’s first lesson—“in man dwells love,” and the nature of human love is that it costs something and runs counter to our needs.

The angel becomes the shoemaker’s assistant. When a frightening “man of iron” orders boots to last a year, the angel, who foresees the man’s imminent death, makes funeral slippers instead. He thereby learns his second lesson, that uncertainty governs human life. Unlike angels, people can never be sure of God’s will or even that He exists. And because people cannot know the future, they mistake their own needs.

When the angel encounters the woman who, out of sheer gratuitous pity, adopted the orphan girls whose mother the angel tried to save, he learns his final lesson: although people imagine they live by their own efforts, they really live because of human love. Mortal ourselves, we see our mortality in others. When people truly love, the sense of death is never absent. Far from destroying life’s meaning, death creates its distinctive value and the special kind of love that people live by.

“What People Live By” is, I think, much more profound than On Life or the writings in Tolstoy as Philosopher. The critical edition of On Life, the first English translation since 1934 and the only carefully annotated one, allows us to see Tolstoy’s struggle to believe that death does not really exist. The brief selections in Tolstoy as Philosopher, most translated into English for the first time, show his preliminary attempts to work out his ideas or, in his last writings, to convey them as succinctly as possible. Both volumes represent important contributions, but Tolstoy as Philosopher suffers from the translator’s poor, at times risible English: “science washed its hands off of them”; “cordial knowledge” rather than “knowledge of the heart”; and, instead of the Boer War, the “Boorish war.”

If one overlooks these infelicities, one embarks on a fascinating journey into how a great writer struggled with existential fears. “The old magician stands before me, alien to all, a solitary traveler through all the deserts of thought in search of an all-embracing truth he has not found,” Gorky wrote after Tolstoy’s death. Gorky’s Tolstoy meditated so constantly on death that it became a sort of companion he could not do without:

It seemed sometimes as though this old sorcerer were playing with death, coquetting with her, trying somehow to deceive her, saying: “I am not afraid of thee, I love thee, long for thee,” and at the same time peering at death with his keen little eyes. “What art thou like?” “What follows thee hereafter?” “Wilt thou destroy me altogether, or will something in me go on living?”

This Issue

June 22, 2023

Fireball Over Siberia

Who Are the Taliban Now?

Meow!